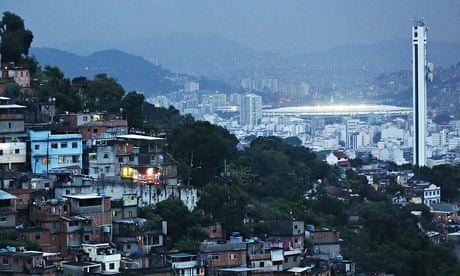

‘There can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity.’ Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

The US college admissions scandal is fascinating, if not surprising. Over 30 wealthy parents have been criminally charged over a scheme in which they allegedly paid a company large sums of money to get their children into top universities. The duplicity involved was extreme: everything from paying off university officials to inventing learning disabilities to facilitate cheating on standardized tests. One father even faked a photo of his son pole vaulting in order to convince admissions officers that the boy was a star athlete.

It’s no secret that wealthy people will do nearly anything to get their kids into good schools. But this scandal only begins to reveal the lies that sustain the American idea of meritocracy. William “Rick” Singer, who admitted to orchestrating the scam, explained that there are three ways in which a student can get into the college of their choice: “There is a front door which is you get in on your own. The back door is through institutional advancement, which is ten times as much money. And I’ve created this side door.” The “side door” he’s referring to is outright crime, literally paying bribes and faking test scores. It’s impossible to know how common that is, but there’s reason to suspect it’s comparatively rare. Why? Because for the most part, the wealthy don’t need to pay illegal bribes. They can already pay perfectly legal ones.

In his 2006 book, The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges, Daniel Golden exposes the way that the top schools favor donors and the children of alumni. A Duke admissions officer recalls being given being given a box of applications she had intended to reject, but which were returned to her for “special” reconsideration. In cases where parents are expected to give very large donations upon a student’s admission, the applicant may be described as an “institutional development” candidate—letting them in would help develop the institution. Everyone by now is familiar with the way the Kushner family bought little Jared a place at Harvard. It only took $2.5m to convince the school that Jared was Harvard material.

The inequality goes so much deeper than that, though. It’s not just donations that put the wealthy ahead. Children of the top 1% (and the top 5%, and the top 20%) have spent their entire lives accumulating advantages over their counterparts at the bottom. Even in first grade the differences can be stark: compare the learning environment at one of Detroit’s crumbling public elementary schools to that at a private elementary school that costs tens of thousands of dollars a year. There are high schools, such as Phillips Academyin Andover, Massachusetts, that have billion dollar endowments. Around the country, the level of education you receive depend on how much money your parents have.

Even if we equalized public school funding, and abolished private schools, some children would be far more equal than others. 2.5m children in the United States go through homelessness every year in this country. The chaotic living situation that comes with poverty makes it much, much harder to succeed. This means that even those who go through Singer’s “front door” have not “gotten in on their own.” They’ve gotten in partly because they’ve had the good fortune to have a home life conducive to their success.

People often speak about “equality of opportunity” as the American aspiration. But having anything close to equal opportunity would require a radical re-engineering of society from top to bottom. As long as there are large wealth inequalities, there will be colossal differences in the opportunities that children have. No matter what admissions criteria are set, wealthy children will have the advantage. If admissions officers focus on test scores, parents will pay for extra tutoring and test prep courses. If officers focus instead on “holistic” qualities, pare. It’s simple: wealth always confers greater capacity to give your children the edge over other people’s children. If we wanted anything resembling a “meritocracy,” we’d probably have to start by instituting full egalitarian communism.

In reality, there can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity. The main function of the concept is to assure elites that they deserve their position in life. It eases the “anxiety of affluence,” that nagging feeling that they might be the beneficiaries of the arbitrary “birth lottery” rather than the products of their own individual ingenuity and hard work.

There’s something perverse about the whole competitive college system. But we can imagine a different world. If everyone was guaranteed free, high-quality public university education, and a public school education matched the quality of a private school education, there wouldn’t be anything to compete for.

Instead of the farce of the admissions process, by which students have to jump through a series of needless hoops in order to prove themselves worthy of being given a good education, just admit everyone who meets a clearly-established threshold for what it takes to do the coursework. It’s not as if the current system is selecting for intelligence or merit. The school you went to mostly tells us what economic class your parents were in. But it doesn’t have to be that way.