The Professional Footballers’ Association shows what can be achieved when everyone is working for the same goal

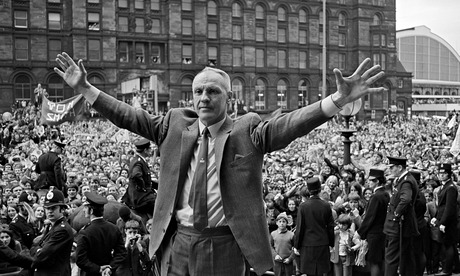

“The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That’s how I see football, that’s how I see life.” So said Bill Shankly, legend of Liverpool Football Club.

Liverpool fans (like me) who lovingly quote Shankly’s words are often told that we’re idealists; that his egalitarian vision is a far cry from the reality of contemporary football. But although socialism is going a bit far, Shankly may have had a point: because it is in British professional football that we find one of the most successful examples of modern trade unionism.

The Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) is the only trade union in the country to have 100% membership, and its principle success lies in its remarkable collective bargaining agreement, which applies to all professional footballers. It offers players numerous protections, including sickness arrangements, insurance in case of injury, post-retirement obligations and disciplinary proceedings (in which the PFA plays a central part).

Collective bargaining is the mechanism that allows workers to negotiate with employers as a whole workforce instead of as individuals. It puts workers in a more powerful position to obtain better terms and conditions, and can establish industry standards. Areport released this week by the Institute for Employment Rights demonstrates that collective bargaining can reduce pay inequality, narrow the gender pay gap, and protect employees from wage cuts during times of financial crisis. It can also reduce income inequality across society. The report notes: “When collective bargaining coverage began to fall in the 1980s, average wages also fell. As the number of workers covered by collective agreements has continued to decline, income inequality has rapidly grown.”

As only one in four British workers are now covered by collective bargaining, the PFA’s agreement is quite exceptional. In practice it means that all footballers are subject to exactly the same terms and conditions, regardless of whom they play for: a player for Luton Town will be treated in exactly the same way by his club as Cesc Fábregas will be for Chelsea. The ethos behind it is that every player puts in the same 90 minutes and should be valued in the same way.

In this respect, the PFA’s agreement is about building solidarity between leagues: the players in better negotiating positions (such as Fábregas) use their power, through the PFA, to improve the terms and conditions of every union member. As the career of a professional footballer lasts an average of just eight years, good terms and conditions are vital – especially for the players who are not in the position to earn top salaries or be offered sponsorship deals.

The PFA has fought to establish itself as an essential part of the professional game and is involved in all key decisions on regulations and how football is run in England. It recently played a pivotal role in ensuring that Portsmouth survived after its financial troubles, which was made possible by applying the “football creditors rule”. This rule is a protection negotiated by the union, which prioritises the players as creditors and imposes an obligation on any new owners to work with the union and honour existing contracts. As a result of this regulation and the solidarity of the players, every one of the 60 clubs that have gone into administration have survived, and remain an integral part of their communities.

Contradicting some employers who seek to undermine the strength of trade unions in workplaces, the PFA has demonstrated that unions – and by extension, workers themselves – are an essential component of industry, and can be good for employers too if they are trusted to take an active role in negotiations.

The case of Portsmouth FC begs the question of what other businesses might have survived administration during the past four years of recession if all unions were afforded the same level of trust that the PFA has been. Of course, the PFA is helped by the fact that footballers’ skills are very specific, but there is no reason why other industries can’t emulate its success by promoting trade unions in the workplace. Not doing so forces workers into a battle with employers, which doesn’t seem beneficial to either party.

What I find so extraordinary about the PFA is that it contradicts rightwing arguments that collective bargaining and trade unions are bad for business. When Governor Scott Walker outlawed collective bargaining in Wisconsin in 2012, he said: “The action today will help ensure Wisconsin has a business climate.”

We’ve been told for so long that better trade union rights will destroy the economy, and yet here is evidence of the benefits of strong trade unions being beamed into the living rooms of millions of people every weekend. As Nick Cusack, assistant chief executive of the PFA, puts it: “The PFA is the players’ greatest supporter. It shows trade unions can achieve a great deal of protections for workers. We’d like to see similar protections for workers across all industries.”

So there you have it. If you’re thinking of approaching your manager to get a better deal on your sick leave, think again. You might be better off talking to Wayne Rooney.