Holly Baxter in The Independent

Watching the absurdity that is TrainGate unfold last night, I couldn’t help but feel that this was a real David and Goliath moment. Isn’t it nice when a billionaire tax-avoiding business magnate with a knighthood takes on a cruel and calculating powerhouse like Labour’s autocratically-minded leader of the opposition and wins? Isn’t it heartening to see the mainstream media take Richard Branson’s side for once, rather than deferring to the statements of a political figure who probably has lots to gain financially from the renationalisation of the railways? After all, it’s not like Branson, the owner of a private company that operates trains, would be affected by things like that. So I think we can all agree that, at the very least, his motives are pure and driven by a rigorous pursuit of objective justice and truth. As for Corbyn, who knows what devious schemes he could have up his sleeve once he’s allowed to hand control of some public transport back to the taxpayer? Isn’t that how Nazi Germany started?

As a born-and-bred Geordie who moved to London for university and stayed for work, I’ve taken the same Newcastle-bound train from London that Jeremy Corbyn sat on the floor of more times than I could count. In case anyone’s actually interested, I can categorically state that it was a lot more pleasant affair when East Coast Trains – the last nationalised arm of British railways – was running the show. The first thing that happened when it was sold off to Virgin was that prices went up and the loyalty scheme which allowed you to accrue points and use them to buy future journeys was stopped (it was replaced with a Nectar Points collaboration and a scheme that encourages you to collect Flying Club miles – two laughable air miles per £1 spent – which, you guessed it, can only be used on Virgin Atlantic planes).

Virgin might have released a press release (yes, for real) about Jeremy Corbyn’s journey this week, claiming that he’d find brilliantly cheap rail fares on their trains in future if he booked in advance, but the £120 return ticket to Durham that I bought weeks in advance for a friend’s wedding this weekend isn’t an anomaly. London to Durham is a journey of two and a half hours. The ridiculous fact that £90 is the cheapest I’ve ever seen a return ticket for it since Virgin took over speaks for itself.

Whether Corbyn sat on the floor to make a point, or because he didn’t look properly in all of the coaches for free seats, or because there were a couple of seats dotted about but he needed a few together for his team is immaterial to me. I’ve spent more than one Christmas Eve sitting curled up inside the luggage rack on the four-hour slow service back to my hometown because even the corridors are too packed to fit into, and I’ve paid extortionate amounts for the privilege. I know what Virgin Trains’ service on the east coast lines are like, even at their least crowded and their very best. A chirpy press release is, of course, going to talk up the “excellent offerings” available from London to Newcastle – but those people have never tried to eat one of their microwaved paninis or operate their on-board wifi, which, to put it kindly, exists more in the conceptual than the physical plane.

Privatised railways are a win for big businesses for obvious reasons: you can’t operate more than one train on one part of a railway line at one time; it’s not like selling a number of competing products together in a shop. Since new lines are hardly ever built, all a business really has to do is have enough money to buy up a monopoly on people’s journeys through whichever part of Britain it chooses. Then – hey presto! – guaranteed sky-high prices with the potential to increase exponentially, since your customer base has very little choice in the matter but to pay up or not travel at all. It’s a naturally uncompetitive business, which makes it a very good candidate for nationalisation and a very good profit-maker for companies with their eyes on the prize. Rail ticket prices, after all, go up like clockwork every year.

Astounded as I am by the fact that people have leapt on what is essentially one of the most boring political stories to have ever hit the headlines, I do support Corbyn’s policy of rail nationalisation in theory. Whether he sat on the floor and announced to camera that ram-packed trains are “a problem that many passengers face every day” as a publicity stunt or after only a half-hearted poke around for seats doesn’t concern me; the simple fact is that the statement is true.

What does concern me, however, is the way in which a discussion about one man sitting on the floor of a packed train has escalated into something which people are now referring to as TrainGate by anti-Corbyn factions, as if accidentally walking past a couple of unreserved seats on a train is genuinely comparable to one of modern America’s most controversial political scandals. I know this has been said a lot in the last few weeks, but really, Labour, have you lost your mind?

“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Thursday 25 August 2016

Wednesday 24 August 2016

How tricksters make you see what they want you to see

By David Robson in the BBC

Could you be fooled into “seeing” something that doesn’t exist?

Matthew Tompkins, a magician-turned-psychologist at the University of Oxford, has been investigating the ways that tricksters implant thoughts in people’s minds. With a masterful sleight of hand, he can make a poker chip disappear right in front of your eyes, or conjure a crayon out of thin air.

And finally, let’s watch the “phantom vanish trick”, which was the focus of his latest experiment:

Although interesting in themselves, the first three videos are really a warm-up for this more ambitious illusion, in which Tompkins tries to plant an image in the participant’s minds using the power of suggestion alone.

Around a third of his participants believed they had seen Tompkins take an object from the pot and tuck it into his hand – only to make it disappear later on. In fact, his fingers were always empty, but his clever pantomiming created an illusion of a real, visible object.

How is that possible? Psychologists have long known that the brain acts like an expert art restorer, touching up the rough images hitting our retina according to context and expectation. This “top-down processing” allows us to build a clear picture from the barest of details (such as this famous picture of the “Dalmatian in the snow”). It’s the reason we can make out a face in the dark, for instance. But occasionally, the brain may fill in too many of the gaps, allowing expectation to warp a picture so that it no longer reflects reality. In some ways, we really do see what we want to see.

This “top-down processing” is reflected in measures of brain activity, and it could easily explain the phantom vanish trick. The warm-up videos, the direction of his gaze, and his deft hand gestures all primed the participants’ brains to see the object between his fingers, and for some participants, this expectation overrode the reality in front of their eyes.

Tuesday 23 August 2016

Sex on campus isn't what you think: what 101 student journals taught me

Lisa Wade in The Guardian

Moments before it happened, Cassidy, Jimena and Declan were sitting in the girls’ shared dorm room, casually chatting about what the cafeteria might be offering for dinner that night. They were just two weeks into their first year of college and looking forward to heading down to the meal hall – when suddenly Declan leaned over, grabbed the waist of Cassidy’s jeans, and pulled her crotch toward his face, proclaiming: “Dinner’s right here!”

Sitting on her lofted bunk bed, Jimena froze. Across the small room, Cassidy squealed with laughter, fell back onto her bed and helped Declan strip off her clothes. “What is happening!?” Jimena cried as Declan pushed his cargo shorts down and jumped under the covers with her roommate. “Sex is happening!” Cassidy said. It was four o’clock in the afternoon.

Cassidy and Declan proceeded to have sex, and Jimena turned to face her computer. When I asked her why she didn’t flee the room, she explained: “I was in shock.” Staying was strangely easier than leaving, she said, because the latter would have required her to turn her body toward the couple, climb out of her bunk, gather her stuff, and find the door, all with her eyes open. So, she waited it out, focusing on a television show played on her laptop in front of her, and catching reflected glimpses of Declan’s bobbing buttocks on her screen. That was the first time Cassidy had sex in front of her. By the third, she’d learned to read the signs and get out before it was too late.

'What is happening!?' Jimena cried. 'Sex is happening!' Cassidy said.

Cassidy and Jimena give us an idea of just how diverse college students’ attitudes toward sex can be. Jimena, a conservative, deeply religious child, was raised by her Nicaraguan immigrant parents to value modesty. Her parents told her, and she strongly believed, that “sex is a serious matter” and that bodies should be “respected, exalted, prized”. Though she didn’t intend to save her virginity for her wedding night, she couldn’t imagine anyone having sex in the absence of love.

Cassidy, an extroverted blond, grew up in a stuffy, mostly white, suburban neighborhood. She was eager to grasp the new freedoms that college offered and didn’t hesitate. On the day that she moved into their dorm, she narrated her Tinder chats aloud to Jimena as she looked to find a fellow student to hook up with. Later that evening she had sex with a match in his room, then went home and told Jimena everything. Jimena was “astounded” but, as would soon become clear, Cassidy was just warming up.

The cloisters at New College Oxford. Photograph: Alamy

Students like Cassidy have been hypervisible in news coverage of hookup culture, giving the impression that most college students are sexually adventurous. For years we’ve debated whether this is good or bad, only to discover, much to our surprise, that students aren’t having as much sex as we thought. In fact, they report the same number of sexual partners as their parents did at their age and are even more likely than previous generations to be what one set of scholars grimly refers to as “sexually inactive”.

One conclusion is to think that campus hookup culture is a myth, a tantalizing, panic-inducing, ultimately untrue story. But to think this is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is. It can’t be measured in sexual activity – whether high or low – because it’s not a behavior, it’s an ethos, an atmosphere, a milieu. A hookup culture is an environment that idealizes and promotes casual sexual encounters over other kinds, regardless of what students actually want or are doing. And it isn’t a myth at all.

I followed 101 students as part of the research for my book American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus. I invited students at two liberal arts schools to submit journals each week for a full semester, in which they wrote as much or as little as they liked about sex and romance on campus. The documents they submitted – varyingly rants, whispered gossip, critical analyses, protracted tales or simple streams of consciousness – came to over 1,500 single-spaced pages and exceeded a million words. To protect students’ confidentiality, I don’t use their real names or reveal the colleges they attend.

My read of these journals revealed four main categories of students. Cassidy and Declan were “enthusiasts”, students who enjoyed casual sex unequivocally. This 14% genuinely enjoyed hooking up and research suggests that they thrive. Jimena was as “abstainer”, one of the 34% who voluntary opted out in their first year. Another 8% abstained because they were in monogamous relationships. The remaining 45% were “dabblers”, students who were ambivalent about casual sex but succumbed to temptation, peer pressure or a sense of inevitability. Other more systematic quantitative research produces similar percentages.

These numbers show that students can opt out of hooking up, and many do. But my research makes clear that they can’t opt out of hookup culture. Whatever choice they make, it’s made meaningful in relationship to the culture. To participate gleefully, for example, is to be its standard bearer, even while being a numerical minority. To voluntarily abstain or commit to a monogamous relationship is to accept marginalization, to be seen as socially irrelevant and possibly sexually repressed. And to dabble is a way for students to bargain with hookup culture, accepting its terms in the hopes that it will deliver something they want.

Burke, for example, was a dabbler. He was strongly relationship-oriented, but his peers seemed to shun traditional dating. “It’s harder to ask someone out than it is to ask someone to go back to your room after fifteen minutes of chatting,” he observed wryly. He resisted hooking up, but “close quarters” made it “extremely easy” to occasionally fall into bed with people, especially when drunk. He always hoped his hookups would turn into something more – which is how most relationships form in hookup culture – but they never did.

‘To think that campus hookup culture is a myth … is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is.’ Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

Wren dabbled, too. She identified as pansexual and had been hoping for a “queer haven” in college, but instead found it to be “quietly oppressive”. Her peers weren’t overtly homophobic and in classrooms they eagerly theorized queer sex, but at parties they “reverted back into gendered codes” and “masculine bullshit”. So she hooked up a little, but not as much as she would have liked.

My abstainers simply decided not to hook up at all. Some of these, like Jimena, were opposed to casual sex no matter the context, but most just weren’t interested in “hot”, “meaningless” sexual encounters. Sex in hookup culture isn’t just casual, it’s aggressively slapdash, excluding not just love, but also fondness and sometimes even basic courtesy.

Hookup culture prevails, even though it serves only a minority of students, because cultures don’t reflect what is, but a specific group’s vision of what should be. The students who are most likely to qualify as enthusiasts are also more likelythan other kinds of students to be affluent, able-bodied, white, conventionally attractive, heterosexual and male. These students know – whether consciously or not – that they can afford to take risks, protected by everything from social status to their parents’ pocketbooks.

Students who don’t carry these privileges, especially when they are disadvantaged in many different ways at once, are often pushed or pulled out of hooking up. One of my African American students, Jaslene, stated bluntly that hooking up isn’t “for black people”, referring specifically to a white standard of beauty for women that disadvantaged women like her in the erotic marketplace. She felt pushed out. Others pulled away. “Some of us with serious financial aid and grants,” said one of my students with an athletic scholarship, “tend to avoid high-risk situations”.

Hookup culture, then, isn’t what the majority of students want, it’s the privileging of the sexual lifestyle most strongly endorsed by those with the most power on campus, the same people we see privileged in every other part of American life. These students, as one Latina observed, “exude dominance”. On the quad, they’re boisterous and engage in loud greetings. They sunbathe and play catch on the green at the first sign of spring. At games, they paint their faces and sing fight songs. They use the campus as their playground. Their bodies – most often slim, athletic and well-dressed – convey an assured calm; they move among their peers with confidence and authority. Online, social media is saturated with their chatter and late night snapshots.

On big party nights, they fill residence halls with activity. Students who don’t party, who have no interest in hooking up, can’t help but know they’re there. “You can hear every conversation occurring in the hallway even with your door closed,” one of my abstainers reported. For hours she would listen to the “click-clacking of high heels” and exchanged reassurances of “Shut up! You look hot!” Eventually there would be a reprieve, but revelers always return drunker and louder.

The morning after, college cafeterias ring with a ritual retelling of the night before. Students who have nothing to contribute to these conversations are excluded just by virtue of having nothing to say. They perhaps eat at other tables, but the raised voices that come with excitement carry. At the gym, in classes, and at the library, flirtations lay the groundwork for the coming weekend. Hookup culture reaches into every corner of campus.

The conspicuousness of hookup culture’s most enthusiastic proponents makes it seem as if everyone is hooking up all the time. In one study students guessed that their peers were doing it 50 times a year, 25 times what the numbers actually show. In another, young men figured that 80% of college guys were having sex any given weekend. They would have been closer to the truth if they were guessing the percentage of men who’d ever had sex.

••

College students aren’t living up to their reputation and hookup culture is part of why. It offers only one kind of sexual experiment, a sexually hot, emotionally cold encounter that suits only a minority of students well. Those who dabble in it often find that their experiences are as mixed as their feelings. One-in-three students say that their sexual encounters have been “traumatic” or “very difficult to handle”. Almost two dozen studies have documented feelings of sexual regret,frustration, disappointment, distress and inadequacy. Many students decide, if hookups are their only option, they’d rather not have sex at all.

We’ve discovered that hookup culture isn’t the cause for concern that some once felt it was, but neither is it the utopia that others hoped. If the goal is to enable young people to learn about and share their sexualities in ways that help them grow to be healthy adults (if they want to explore at all), we’re not there yet. But the more we understand about hookup culture, the closer we’ll be able to get.

Moments before it happened, Cassidy, Jimena and Declan were sitting in the girls’ shared dorm room, casually chatting about what the cafeteria might be offering for dinner that night. They were just two weeks into their first year of college and looking forward to heading down to the meal hall – when suddenly Declan leaned over, grabbed the waist of Cassidy’s jeans, and pulled her crotch toward his face, proclaiming: “Dinner’s right here!”

Sitting on her lofted bunk bed, Jimena froze. Across the small room, Cassidy squealed with laughter, fell back onto her bed and helped Declan strip off her clothes. “What is happening!?” Jimena cried as Declan pushed his cargo shorts down and jumped under the covers with her roommate. “Sex is happening!” Cassidy said. It was four o’clock in the afternoon.

Cassidy and Declan proceeded to have sex, and Jimena turned to face her computer. When I asked her why she didn’t flee the room, she explained: “I was in shock.” Staying was strangely easier than leaving, she said, because the latter would have required her to turn her body toward the couple, climb out of her bunk, gather her stuff, and find the door, all with her eyes open. So, she waited it out, focusing on a television show played on her laptop in front of her, and catching reflected glimpses of Declan’s bobbing buttocks on her screen. That was the first time Cassidy had sex in front of her. By the third, she’d learned to read the signs and get out before it was too late.

'What is happening!?' Jimena cried. 'Sex is happening!' Cassidy said.

Cassidy and Jimena give us an idea of just how diverse college students’ attitudes toward sex can be. Jimena, a conservative, deeply religious child, was raised by her Nicaraguan immigrant parents to value modesty. Her parents told her, and she strongly believed, that “sex is a serious matter” and that bodies should be “respected, exalted, prized”. Though she didn’t intend to save her virginity for her wedding night, she couldn’t imagine anyone having sex in the absence of love.

Cassidy, an extroverted blond, grew up in a stuffy, mostly white, suburban neighborhood. She was eager to grasp the new freedoms that college offered and didn’t hesitate. On the day that she moved into their dorm, she narrated her Tinder chats aloud to Jimena as she looked to find a fellow student to hook up with. Later that evening she had sex with a match in his room, then went home and told Jimena everything. Jimena was “astounded” but, as would soon become clear, Cassidy was just warming up.

The cloisters at New College Oxford. Photograph: Alamy

Students like Cassidy have been hypervisible in news coverage of hookup culture, giving the impression that most college students are sexually adventurous. For years we’ve debated whether this is good or bad, only to discover, much to our surprise, that students aren’t having as much sex as we thought. In fact, they report the same number of sexual partners as their parents did at their age and are even more likely than previous generations to be what one set of scholars grimly refers to as “sexually inactive”.

One conclusion is to think that campus hookup culture is a myth, a tantalizing, panic-inducing, ultimately untrue story. But to think this is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is. It can’t be measured in sexual activity – whether high or low – because it’s not a behavior, it’s an ethos, an atmosphere, a milieu. A hookup culture is an environment that idealizes and promotes casual sexual encounters over other kinds, regardless of what students actually want or are doing. And it isn’t a myth at all.

I followed 101 students as part of the research for my book American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus. I invited students at two liberal arts schools to submit journals each week for a full semester, in which they wrote as much or as little as they liked about sex and romance on campus. The documents they submitted – varyingly rants, whispered gossip, critical analyses, protracted tales or simple streams of consciousness – came to over 1,500 single-spaced pages and exceeded a million words. To protect students’ confidentiality, I don’t use their real names or reveal the colleges they attend.

My read of these journals revealed four main categories of students. Cassidy and Declan were “enthusiasts”, students who enjoyed casual sex unequivocally. This 14% genuinely enjoyed hooking up and research suggests that they thrive. Jimena was as “abstainer”, one of the 34% who voluntary opted out in their first year. Another 8% abstained because they were in monogamous relationships. The remaining 45% were “dabblers”, students who were ambivalent about casual sex but succumbed to temptation, peer pressure or a sense of inevitability. Other more systematic quantitative research produces similar percentages.

These numbers show that students can opt out of hooking up, and many do. But my research makes clear that they can’t opt out of hookup culture. Whatever choice they make, it’s made meaningful in relationship to the culture. To participate gleefully, for example, is to be its standard bearer, even while being a numerical minority. To voluntarily abstain or commit to a monogamous relationship is to accept marginalization, to be seen as socially irrelevant and possibly sexually repressed. And to dabble is a way for students to bargain with hookup culture, accepting its terms in the hopes that it will deliver something they want.

Burke, for example, was a dabbler. He was strongly relationship-oriented, but his peers seemed to shun traditional dating. “It’s harder to ask someone out than it is to ask someone to go back to your room after fifteen minutes of chatting,” he observed wryly. He resisted hooking up, but “close quarters” made it “extremely easy” to occasionally fall into bed with people, especially when drunk. He always hoped his hookups would turn into something more – which is how most relationships form in hookup culture – but they never did.

‘To think that campus hookup culture is a myth … is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is.’ Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

Wren dabbled, too. She identified as pansexual and had been hoping for a “queer haven” in college, but instead found it to be “quietly oppressive”. Her peers weren’t overtly homophobic and in classrooms they eagerly theorized queer sex, but at parties they “reverted back into gendered codes” and “masculine bullshit”. So she hooked up a little, but not as much as she would have liked.

My abstainers simply decided not to hook up at all. Some of these, like Jimena, were opposed to casual sex no matter the context, but most just weren’t interested in “hot”, “meaningless” sexual encounters. Sex in hookup culture isn’t just casual, it’s aggressively slapdash, excluding not just love, but also fondness and sometimes even basic courtesy.

Hookup culture prevails, even though it serves only a minority of students, because cultures don’t reflect what is, but a specific group’s vision of what should be. The students who are most likely to qualify as enthusiasts are also more likelythan other kinds of students to be affluent, able-bodied, white, conventionally attractive, heterosexual and male. These students know – whether consciously or not – that they can afford to take risks, protected by everything from social status to their parents’ pocketbooks.

Students who don’t carry these privileges, especially when they are disadvantaged in many different ways at once, are often pushed or pulled out of hooking up. One of my African American students, Jaslene, stated bluntly that hooking up isn’t “for black people”, referring specifically to a white standard of beauty for women that disadvantaged women like her in the erotic marketplace. She felt pushed out. Others pulled away. “Some of us with serious financial aid and grants,” said one of my students with an athletic scholarship, “tend to avoid high-risk situations”.

Hookup culture, then, isn’t what the majority of students want, it’s the privileging of the sexual lifestyle most strongly endorsed by those with the most power on campus, the same people we see privileged in every other part of American life. These students, as one Latina observed, “exude dominance”. On the quad, they’re boisterous and engage in loud greetings. They sunbathe and play catch on the green at the first sign of spring. At games, they paint their faces and sing fight songs. They use the campus as their playground. Their bodies – most often slim, athletic and well-dressed – convey an assured calm; they move among their peers with confidence and authority. Online, social media is saturated with their chatter and late night snapshots.

On big party nights, they fill residence halls with activity. Students who don’t party, who have no interest in hooking up, can’t help but know they’re there. “You can hear every conversation occurring in the hallway even with your door closed,” one of my abstainers reported. For hours she would listen to the “click-clacking of high heels” and exchanged reassurances of “Shut up! You look hot!” Eventually there would be a reprieve, but revelers always return drunker and louder.

The morning after, college cafeterias ring with a ritual retelling of the night before. Students who have nothing to contribute to these conversations are excluded just by virtue of having nothing to say. They perhaps eat at other tables, but the raised voices that come with excitement carry. At the gym, in classes, and at the library, flirtations lay the groundwork for the coming weekend. Hookup culture reaches into every corner of campus.

The conspicuousness of hookup culture’s most enthusiastic proponents makes it seem as if everyone is hooking up all the time. In one study students guessed that their peers were doing it 50 times a year, 25 times what the numbers actually show. In another, young men figured that 80% of college guys were having sex any given weekend. They would have been closer to the truth if they were guessing the percentage of men who’d ever had sex.

••

College students aren’t living up to their reputation and hookup culture is part of why. It offers only one kind of sexual experiment, a sexually hot, emotionally cold encounter that suits only a minority of students well. Those who dabble in it often find that their experiences are as mixed as their feelings. One-in-three students say that their sexual encounters have been “traumatic” or “very difficult to handle”. Almost two dozen studies have documented feelings of sexual regret,frustration, disappointment, distress and inadequacy. Many students decide, if hookups are their only option, they’d rather not have sex at all.

We’ve discovered that hookup culture isn’t the cause for concern that some once felt it was, but neither is it the utopia that others hoped. If the goal is to enable young people to learn about and share their sexualities in ways that help them grow to be healthy adults (if they want to explore at all), we’re not there yet. But the more we understand about hookup culture, the closer we’ll be able to get.

Why scientists are losing the fight to communicate science to the public

Richard P Grant in The Guardian

A video did the rounds a couple of years ago, of some self-styled “skeptic” disagreeing – robustly, shall we say – with an anti-vaxxer. The speaker was roundly cheered by everyone sharing the video – he sure put that idiot in their place!

Scientists love to argue. Cutting through bullshit and getting to the truth of the matter is pretty much the job description. So it’s not really surprising scientists and science supporters frequently take on those who dabble in homeopathy, or deny anthropogenic climate change, or who oppose vaccinations or genetically modified food.

It makes sense. You’ve got a population that is – on the whole – not scientifically literate, and you want to persuade them that they should be doing a and b (but not c) so that they/you/their children can have a better life.

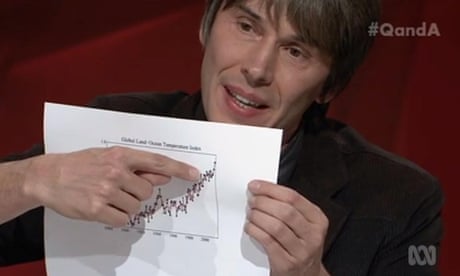

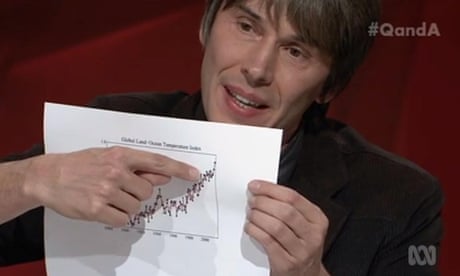

Brian Cox was at it last week, performing a “smackdown” on a climate change denier on the ABC’s Q&A discussion program. He brought graphs! Knockout blow.

Q&A smackdown: Brian Cox brings graphs to grapple with Malcolm Roberts

And yet … it leaves me cold. Is this really what science communication is about? Is this informing, changing minds, winning people over to a better, brighter future?

I doubt it somehow.

There are a couple of things here. And I don’t think it’s as simple as people rejecting science.

First, people don’t like being told what to do. This is part of what Michael Gove was driving at when he said people had had enough of experts. We rely on doctors and nurses to make us better, and on financial planners to help us invest. We expect scientists to research new cures for disease, or simply to find out how things work. We expect the government to try to do the best for most of the people most of the time, and weather forecasters to at least tell us what today was like even if they struggle with tomorrow.

But when these experts tell us how to live our lives – or even worse, what to think – something rebels. Especially when there is even the merest whiff of controversy or uncertainty. Back in your box, we say, and stick to what you’re good at.

We saw it in the recent referendum, we saw it when Dame Sally Davies said wine makes her think of breast cancer, and we saw it back in the late 1990s when the government of the time told people – who honestly, really wanted to do the best for their children – to shut up, stop asking questions and take the damn triple vaccine.

Which brings us to the second thing.

On the whole, I don’t think people who object to vaccines or GMOs are at heart anti-science. Some are, for sure, and these are the dangerous ones. But most people simply want to know that someone is listening, that someone is taking their worries seriously; that someone cares for them.

It’s more about who we are and our relationships than about what is right or true.

This is why, when you bring data to a TV show, you run the risk of appearing supercilious and judgemental. Even – especially – if you’re actually right.

People want to feel wanted and loved. That there is someone who will listen to them. To feel part of a family.

The physicist Sabine Hossenfelder gets this. Between contracts one time, she set up a “talk to a physicist” service. Fifty dollars gets you 20 minutes with a quantum physicist … who will listen to whatever crazy idea you have, and help you understand a little more about the world.

How many science communicators do you know who will take the time to listen to their audience? Who are willing to step outside their cosy little bubble and make an effort to reach people where they are, where they are confused and hurting; where they need?

Atul Gawande says scientists should assert “the true facts of good science” and expose the “bad science tactics that are being used to mislead people”. But that’s only part of the story, and is closing the barn door too late.

Because the charlatans have already recognised the need, and have built the communities that people crave. Tellingly, Gawande refers to the ‘scientific community’; and he’s absolutely right, there. Most science communication isn’t about persuading people; it’s self-affirmation for those already on the inside. Look at us, it says, aren’t we clever? We are exclusive, we are a gang, we are family.

That’s not communication. It’s not changing minds and it’s certainly not winning hearts and minds.

It’s tribalism.

A video did the rounds a couple of years ago, of some self-styled “skeptic” disagreeing – robustly, shall we say – with an anti-vaxxer. The speaker was roundly cheered by everyone sharing the video – he sure put that idiot in their place!

Scientists love to argue. Cutting through bullshit and getting to the truth of the matter is pretty much the job description. So it’s not really surprising scientists and science supporters frequently take on those who dabble in homeopathy, or deny anthropogenic climate change, or who oppose vaccinations or genetically modified food.

It makes sense. You’ve got a population that is – on the whole – not scientifically literate, and you want to persuade them that they should be doing a and b (but not c) so that they/you/their children can have a better life.

Brian Cox was at it last week, performing a “smackdown” on a climate change denier on the ABC’s Q&A discussion program. He brought graphs! Knockout blow.

Q&A smackdown: Brian Cox brings graphs to grapple with Malcolm Roberts

And yet … it leaves me cold. Is this really what science communication is about? Is this informing, changing minds, winning people over to a better, brighter future?

I doubt it somehow.

There are a couple of things here. And I don’t think it’s as simple as people rejecting science.

First, people don’t like being told what to do. This is part of what Michael Gove was driving at when he said people had had enough of experts. We rely on doctors and nurses to make us better, and on financial planners to help us invest. We expect scientists to research new cures for disease, or simply to find out how things work. We expect the government to try to do the best for most of the people most of the time, and weather forecasters to at least tell us what today was like even if they struggle with tomorrow.

But when these experts tell us how to live our lives – or even worse, what to think – something rebels. Especially when there is even the merest whiff of controversy or uncertainty. Back in your box, we say, and stick to what you’re good at.

We saw it in the recent referendum, we saw it when Dame Sally Davies said wine makes her think of breast cancer, and we saw it back in the late 1990s when the government of the time told people – who honestly, really wanted to do the best for their children – to shut up, stop asking questions and take the damn triple vaccine.

Which brings us to the second thing.

On the whole, I don’t think people who object to vaccines or GMOs are at heart anti-science. Some are, for sure, and these are the dangerous ones. But most people simply want to know that someone is listening, that someone is taking their worries seriously; that someone cares for them.

It’s more about who we are and our relationships than about what is right or true.

This is why, when you bring data to a TV show, you run the risk of appearing supercilious and judgemental. Even – especially – if you’re actually right.

People want to feel wanted and loved. That there is someone who will listen to them. To feel part of a family.

The physicist Sabine Hossenfelder gets this. Between contracts one time, she set up a “talk to a physicist” service. Fifty dollars gets you 20 minutes with a quantum physicist … who will listen to whatever crazy idea you have, and help you understand a little more about the world.

How many science communicators do you know who will take the time to listen to their audience? Who are willing to step outside their cosy little bubble and make an effort to reach people where they are, where they are confused and hurting; where they need?

Atul Gawande says scientists should assert “the true facts of good science” and expose the “bad science tactics that are being used to mislead people”. But that’s only part of the story, and is closing the barn door too late.

Because the charlatans have already recognised the need, and have built the communities that people crave. Tellingly, Gawande refers to the ‘scientific community’; and he’s absolutely right, there. Most science communication isn’t about persuading people; it’s self-affirmation for those already on the inside. Look at us, it says, aren’t we clever? We are exclusive, we are a gang, we are family.

That’s not communication. It’s not changing minds and it’s certainly not winning hearts and minds.

It’s tribalism.

Why economic punditry leaves you worrying about the wrong big numbers

Ben Chu in The Independent

Big numbers are all around us, shaping our political debates, influencing the way we think about things. For instance we hear a great deal about the prodigious size of the national debt: £1,603bn in July according to the latest official statistics.

There has been a proliferation of stories about the aggregate deficit of pension schemes, which has jumped to an estimated £1trn in the wake of the Brexit vote. And how could we forget that record net migration figure of 333,000, which figured so prominently in the recent European Union referendum campaign?

Yet there are other massive numbers we seldom hear about. The Office for National Statistics published some estimates for the “national balance sheet” last week. This is the place to look if you want really big numbers. They showed that the aggregate value of the UK’s residential housing stock in 2015 was £5.2 trillion – that’s up £350bn in just 12 months. A lot of people are a lot wealthier than they were a year ago.

That’s property wealth. What about the total value of households’ financial assets? According to the ONS, that stands at £6.2 trillion – up £113bn over the year. It will be even higher since the Brexit vote. Why? Because those ballooning pension scheme deficits we hear about represent a part of the financial assets of households.

Incidentally, a majority of the national debt, indirectly, represents a financial asset of UK households too. We often forget that for every financial liability there has to be a financial asset.

There’s still a good deal of handwringing in some quarters about the supposedly excessive borrowing of the state. But we don’t tend to hear anything about the debt of the corporate sector these days. The ONS reports that the total debt (loans and bonds combined) of British-based companies in 2015 was £1.35 trilion, pretty much where it was back in 2010.

If debt is something to get excited about, shouldn’t company borrowing be a cause for concern? Not, of course, if companies are borrowing to increase their productive capacities.

Actually, the major problem with corporate balance sheets lies in a different area. The ONS data shows that the corporate sector’s overall stocks of cash rose to £581bn in 2015, up £41bn on last year and a sum representing an astonishing 31 per cent of our GDP. It should be seriously worrying that firms are still choosing to keep so much cash on their balance sheets at a time when we badly need them to invest.

We tend to fret about the wrong big numbers. Consider the data on the liabilities of UK-based financial institutions. If you want a large number try this: £20.5 trillion. And around a quarter of these are financial derivative contracts. Many of those companies are foreign firms with UK operations. But UK banks – which we taxpayers still effectively underwrite because they are “too big to fail” – have aggregate liabilities worth £7.5 trillion.

That’s around four times larger than our GDP, yet Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, has rather strangely suggested he would be comfortable with that figure eventually rising to nine times national income.

Sometimes we fail to appreciate what lies behind the big numbers that shape our debates. The headlines this week said total UK employment grew by 172,000 in the three months to June. But this only tells one part of the story. Other data from the ONS showed that 478,000 people without jobs got them in the quarter, while 317,000 people entered the ranks of the unemployed. That headline figure is a net change in employment figure. And this wasn’t an unusually busy quarter for the jobs market.

This churn goes on constantly, with hundreds of thousands of us leaving jobs and hundreds of thousands taking new ones. The economic threat from the Brexit vote aftermath isn’t just people being made redundant – it’s a slowdown in hiring and that mighty labour market churn.

There’s a similar issue with those ubiquitous net migration figures. Newspapers talk of immigration creating “a new city the size of Newcastle each year” (or some variation on that line). That is rhetoric designed to stir public anxiety.

Yet that’s in context of an estimate of 36 million tourist visits to the UK each year, flows equal to half of the British population. And there are double the number of tourists visits going the other way each year.

What these big numbers emphasise is that we live in a mind-bendingly busy, complex and internationally connected economy. The figures we hear about, and which pundits fixate upon, are often the differences between two, or sometimes more, very large numbers. That bigger context should not be ignored.

The economic risks and fragilities of our economy are not always where we’re invited to believe they are.

Big numbers are all around us, shaping our political debates, influencing the way we think about things. For instance we hear a great deal about the prodigious size of the national debt: £1,603bn in July according to the latest official statistics.

There has been a proliferation of stories about the aggregate deficit of pension schemes, which has jumped to an estimated £1trn in the wake of the Brexit vote. And how could we forget that record net migration figure of 333,000, which figured so prominently in the recent European Union referendum campaign?

Yet there are other massive numbers we seldom hear about. The Office for National Statistics published some estimates for the “national balance sheet” last week. This is the place to look if you want really big numbers. They showed that the aggregate value of the UK’s residential housing stock in 2015 was £5.2 trillion – that’s up £350bn in just 12 months. A lot of people are a lot wealthier than they were a year ago.

That’s property wealth. What about the total value of households’ financial assets? According to the ONS, that stands at £6.2 trillion – up £113bn over the year. It will be even higher since the Brexit vote. Why? Because those ballooning pension scheme deficits we hear about represent a part of the financial assets of households.

Incidentally, a majority of the national debt, indirectly, represents a financial asset of UK households too. We often forget that for every financial liability there has to be a financial asset.

There’s still a good deal of handwringing in some quarters about the supposedly excessive borrowing of the state. But we don’t tend to hear anything about the debt of the corporate sector these days. The ONS reports that the total debt (loans and bonds combined) of British-based companies in 2015 was £1.35 trilion, pretty much where it was back in 2010.

If debt is something to get excited about, shouldn’t company borrowing be a cause for concern? Not, of course, if companies are borrowing to increase their productive capacities.

Actually, the major problem with corporate balance sheets lies in a different area. The ONS data shows that the corporate sector’s overall stocks of cash rose to £581bn in 2015, up £41bn on last year and a sum representing an astonishing 31 per cent of our GDP. It should be seriously worrying that firms are still choosing to keep so much cash on their balance sheets at a time when we badly need them to invest.

We tend to fret about the wrong big numbers. Consider the data on the liabilities of UK-based financial institutions. If you want a large number try this: £20.5 trillion. And around a quarter of these are financial derivative contracts. Many of those companies are foreign firms with UK operations. But UK banks – which we taxpayers still effectively underwrite because they are “too big to fail” – have aggregate liabilities worth £7.5 trillion.

That’s around four times larger than our GDP, yet Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, has rather strangely suggested he would be comfortable with that figure eventually rising to nine times national income.

Sometimes we fail to appreciate what lies behind the big numbers that shape our debates. The headlines this week said total UK employment grew by 172,000 in the three months to June. But this only tells one part of the story. Other data from the ONS showed that 478,000 people without jobs got them in the quarter, while 317,000 people entered the ranks of the unemployed. That headline figure is a net change in employment figure. And this wasn’t an unusually busy quarter for the jobs market.

This churn goes on constantly, with hundreds of thousands of us leaving jobs and hundreds of thousands taking new ones. The economic threat from the Brexit vote aftermath isn’t just people being made redundant – it’s a slowdown in hiring and that mighty labour market churn.

There’s a similar issue with those ubiquitous net migration figures. Newspapers talk of immigration creating “a new city the size of Newcastle each year” (or some variation on that line). That is rhetoric designed to stir public anxiety.

Yet that’s in context of an estimate of 36 million tourist visits to the UK each year, flows equal to half of the British population. And there are double the number of tourists visits going the other way each year.

What these big numbers emphasise is that we live in a mind-bendingly busy, complex and internationally connected economy. The figures we hear about, and which pundits fixate upon, are often the differences between two, or sometimes more, very large numbers. That bigger context should not be ignored.

The economic risks and fragilities of our economy are not always where we’re invited to believe they are.

Follow the money: how left-behind cities can hold their corporate bullies to account

Paul Mason in The Guardian

If you walk along Britain’s poorest streets, the phrase “left behind” – in vogue again after many such places voted to leave the EU – takes on a complex meaning. It’s not just that they are lagging behind the richer, better-connected places. It can seem, as you survey the pound stores and shuttered pubs, that these towns have been discarded: left behind, as in “unwanted on the journey”. Wealth has flowed out of them to somewhere else.

The logical question should be: who did this? Sometimes it’s obvious: in Ebbw Vale, for example, the answer is the Anglo-Dutch steel company Corus, which closed the plant in 2002. In many places it’s not obvious. Jobs seep away; council services are privatised; bus timetables dwindle; the local school gets taken over by a “superhead” from somewhere else, outsourcing the dinner ladies on day one. You can get angry about it, but there is nobody specific to be angry at.

Faced with the same problem, union and community organisers in the US have, in the past 12 months, adopted a novel way of fighting back. Through a campaign group called Hedge Clippers, they have begun tracing the lineages of financial power behind the decisions that affect specific places, and targeting those financiers – pension funds – with a new kind of pressure.

Steve Lerner, one of the instigators of the 1980s Justice for Janitors campaign, which, for the first time, organised migrant cleaning workers in the US, explains how the tactic evolved. “We were organising janitors working for contract cleaning companies: but they’re just middlemen,” he said. “So we targeted the building owners. It turned out they, too, were dependent on banks and pension companies, so we got a trillion dollars worth of pension money to say it won’t invest unless there is decent pay. Then we asked ourselves: OK, what else do they own?”

It turns out, quite a lot. In Baltimore, the city’s privatised water industry hiked its bills. Then, when people started to fall behind in payments, the city agreed to bundle up their unpaid bills into a financial vehicle called a “tax lien” and sell it to investors. The investors can, after two years, evict people from their homes for non-payment.

When campaigners looked at who was buying up the debt, they included an anonymous company linked to one of the biggest hedge funds in America: Fortress Investments, with $23bn worth of assets invested in “the largest pension funds, university endowments and foundations”.

Since the 2008 crisis, with returns on government bonds negative, and stock market dividends depressed, pension funds have been pouring money into the hedge fund sector. “It’s a form of assisted suicide,” Lerner argues: “Workers are investing their pension money into firms whose mission is to destroy us.”

He set up Hedge Clippers, which aims to force pension funds to divest from companies whose investment strategies fuel the cycle of impoverishment.

If you apply the same approach to Britain, you’re dealing with a different ecosystem. No city has yet securitised the unpaid debts of the poor, as Baltimore did. While there is no shortage of predatory lenders to the poor, there are – after a campaign led by Labour MP Stella Creasy – at least elementary controls on them.

However, pension funds are now the biggest source of money for UK hedge funds, according to a Financial Conduct Authority survey last year, with 43% of their money coming from institutional investors. The most obvious act of financial predation is the private finance initiative (PFI), where schools and hospitals were built with vastly lucrative private loans. As a result, the taxpayer is committed to paying back £232bn on assets worth £57bn.

Many pension funds, either directly or indirectly, are investing in the so-called “infrastructure funds” who buy up PFI debt. The investment analyst Preqin found 588 institutional investors worldwide with “a preference for funds targeting PFI”, 40% of which were based in Europe.

Tracing the more complex ways institutional finance is funding the cycle of impoverishment is not easy. What you would want to know, in places such as Stoke-on-Trent or Newport, is not just who took the decisions to close high-value workplaces but, more importantly, who makes the decisions that lead to chronic under-investment now. Governments, including the devolved ones of the UK, spend a lot of time and money effectively bribing global companies to create jobs and keep them in Britain’s depressed areas. Communities themselves have little or no input into the process, which is in any case all carrot and no stick.

Lerner’s initiative in the US grew out of trade union activism, because the unions there learned to follow the money instead of wasting time trying to negotiate with the powerless underlings of global finance. They worked out that, in an age where the workplace and the community can seem like two different spheres of activism, it is the finance system that links the two.

Older ‘left-behind’ voters turned against a political class with values opposed to theirs

Union organising of the unorganised, and community activism in Britain have both traditionally been weak because top-down Labourism has been strong. Faced with PFI, predatory loans, rip-off landlords and privatisation, the British way is to demand legislation, not chain yourself to the door of a Mayfair hedge fund.

With or without Jeremy Corbyn, the near-impossibility of Labour gaining a Commons majority in 2020 – whether because of Scotland, boundary changes, a hostile media or self-destruction – has to refocus the left on to what is possible to achieve from below. We have to start, as the Americans did, by mapping the invisible forces that strip jobs, value and hope out of communities; make them visible; trace their dependencies and then use direct action to kick them in the corporate goolies until they desist.

If you walk along Britain’s poorest streets, the phrase “left behind” – in vogue again after many such places voted to leave the EU – takes on a complex meaning. It’s not just that they are lagging behind the richer, better-connected places. It can seem, as you survey the pound stores and shuttered pubs, that these towns have been discarded: left behind, as in “unwanted on the journey”. Wealth has flowed out of them to somewhere else.

The logical question should be: who did this? Sometimes it’s obvious: in Ebbw Vale, for example, the answer is the Anglo-Dutch steel company Corus, which closed the plant in 2002. In many places it’s not obvious. Jobs seep away; council services are privatised; bus timetables dwindle; the local school gets taken over by a “superhead” from somewhere else, outsourcing the dinner ladies on day one. You can get angry about it, but there is nobody specific to be angry at.

Faced with the same problem, union and community organisers in the US have, in the past 12 months, adopted a novel way of fighting back. Through a campaign group called Hedge Clippers, they have begun tracing the lineages of financial power behind the decisions that affect specific places, and targeting those financiers – pension funds – with a new kind of pressure.

Steve Lerner, one of the instigators of the 1980s Justice for Janitors campaign, which, for the first time, organised migrant cleaning workers in the US, explains how the tactic evolved. “We were organising janitors working for contract cleaning companies: but they’re just middlemen,” he said. “So we targeted the building owners. It turned out they, too, were dependent on banks and pension companies, so we got a trillion dollars worth of pension money to say it won’t invest unless there is decent pay. Then we asked ourselves: OK, what else do they own?”

It turns out, quite a lot. In Baltimore, the city’s privatised water industry hiked its bills. Then, when people started to fall behind in payments, the city agreed to bundle up their unpaid bills into a financial vehicle called a “tax lien” and sell it to investors. The investors can, after two years, evict people from their homes for non-payment.

When campaigners looked at who was buying up the debt, they included an anonymous company linked to one of the biggest hedge funds in America: Fortress Investments, with $23bn worth of assets invested in “the largest pension funds, university endowments and foundations”.

Since the 2008 crisis, with returns on government bonds negative, and stock market dividends depressed, pension funds have been pouring money into the hedge fund sector. “It’s a form of assisted suicide,” Lerner argues: “Workers are investing their pension money into firms whose mission is to destroy us.”

He set up Hedge Clippers, which aims to force pension funds to divest from companies whose investment strategies fuel the cycle of impoverishment.

If you apply the same approach to Britain, you’re dealing with a different ecosystem. No city has yet securitised the unpaid debts of the poor, as Baltimore did. While there is no shortage of predatory lenders to the poor, there are – after a campaign led by Labour MP Stella Creasy – at least elementary controls on them.

However, pension funds are now the biggest source of money for UK hedge funds, according to a Financial Conduct Authority survey last year, with 43% of their money coming from institutional investors. The most obvious act of financial predation is the private finance initiative (PFI), where schools and hospitals were built with vastly lucrative private loans. As a result, the taxpayer is committed to paying back £232bn on assets worth £57bn.

Many pension funds, either directly or indirectly, are investing in the so-called “infrastructure funds” who buy up PFI debt. The investment analyst Preqin found 588 institutional investors worldwide with “a preference for funds targeting PFI”, 40% of which were based in Europe.

Tracing the more complex ways institutional finance is funding the cycle of impoverishment is not easy. What you would want to know, in places such as Stoke-on-Trent or Newport, is not just who took the decisions to close high-value workplaces but, more importantly, who makes the decisions that lead to chronic under-investment now. Governments, including the devolved ones of the UK, spend a lot of time and money effectively bribing global companies to create jobs and keep them in Britain’s depressed areas. Communities themselves have little or no input into the process, which is in any case all carrot and no stick.

Lerner’s initiative in the US grew out of trade union activism, because the unions there learned to follow the money instead of wasting time trying to negotiate with the powerless underlings of global finance. They worked out that, in an age where the workplace and the community can seem like two different spheres of activism, it is the finance system that links the two.

Older ‘left-behind’ voters turned against a political class with values opposed to theirs

Union organising of the unorganised, and community activism in Britain have both traditionally been weak because top-down Labourism has been strong. Faced with PFI, predatory loans, rip-off landlords and privatisation, the British way is to demand legislation, not chain yourself to the door of a Mayfair hedge fund.

With or without Jeremy Corbyn, the near-impossibility of Labour gaining a Commons majority in 2020 – whether because of Scotland, boundary changes, a hostile media or self-destruction – has to refocus the left on to what is possible to achieve from below. We have to start, as the Americans did, by mapping the invisible forces that strip jobs, value and hope out of communities; make them visible; trace their dependencies and then use direct action to kick them in the corporate goolies until they desist.

Seven changes needed to save the euro and the EU

Joseph Stiglitz in The Guardian

To say that the eurozone has not been performing well since the 2008 crisis is an understatement. Its member countries have done more poorly than the European Union countries outside the eurozone, and much more poorly than the United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis.

The worst-performing eurozone countries are mired in depression or deep recession; their condition – think of Greece – is worse in many ways than what economies suffered during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The best-performing eurozone members, such as Germany, look good, but only in comparison; and their growth model is partly based on beggar-thy-neighbour policies, whereby success comes at the expense of erstwhile “partners”.

Four types of explanation have been advanced to explain this state of affairs.Germany likes to blame the victim, pointing to Greece’s profligacy and the debt and deficits elsewhere. But this puts the cart before the horse: Spain and Ireland had surpluses and low debt-to-GDP ratios before the euro crisis. So the crisis caused the deficits and debts, not the other way around.

Deficit fetishism is, no doubt, part of Europe’s problems. Finland, too, has been having trouble adjusting to the multiple shocks it has confronted, with GDP in 2015 around 5.5% below its 2008 peak.

Other “blame the victim” critics cite the welfare state and excessive labour-market protections as the cause of the eurozone’s malaise. Yet some of Europe’s best-performing countries, such as Sweden and Norway, have the strongest welfare states and labour-market protections.

Many of the countries now performing poorly were doing very well – above the European average – before the euro was introduced. Their decline did not result from some sudden change in their labour laws, or from an epidemic of laziness in the crisis countries. What changed was the currency arrangement.

The second type of explanation amounts to a wish that Europe had better leaders, men and women who understood economics better and implemented better policies. Flawed policies – not just austerity, but also misguided so-called structural reforms, which widened inequality and thus further weakened overall demand and potential growth – have undoubtedly made matters worse.

But the eurozone was a political arrangement, in which it was inevitable that Germany’s voice would be loud. Anyone who has dealt with German policymakers over the past third of a century should have known in advance the likely result. Most important, given the available tools, not even the most brilliant economic tsar could not have made the eurozone prosper.

The third set of reasons for the eurozone’s poor performance is a broader rightwing critique of the EU, centred on the eurocrats’ penchant for stifling, innovation-inhibiting regulations. This critique, too, misses the mark. The eurocrats, like labour laws or the welfare state, didn’t suddenly change in 1999, with the creation of the fixed exchange-rate system, or in 2008, with the beginning of the crisis. More fundamentally, what matters is the standard of living, the quality of life. Anyone who denies how much better off we in the west are with our stiflingly clean air and water should visit Beijing.

That leaves the fourth explanation: the euro is more to blame than the policies and structures of individual countries. The euro was flawed at birth. Even the best policymakers the world has ever seen could not have made it work. The eurozone’s structure imposed the kind of rigidity associated with the gold standard. The single currency took away its members’ most important mechanism for adjustment – the exchange rate – and the eurozone circumscribed monetary and fiscal policy.

In response to asymmetric shocks and divergences in productivity, there would have to be adjustments in the real (inflation-adjusted) exchange rate, meaning that prices in the eurozone periphery would have to fall relative to Germany and northern Europe. But, with Germany adamant about inflation – its prices have been stagnant – the adjustment could be accomplished only through wrenching deflation elsewhere. Typically, this meant painful unemployment and weakening unions; the eurozone’s poorest countries, and especially the workers within them, bore the brunt of the adjustment burden. So the plan to spur convergence among eurozone countries failed miserably, with disparities between and within countries growing.

This system cannot and will not work in the long run: democratic politics ensures its failure. Only by changing the eurozone’s rules and institutions can the euro be made to work. This will require seven changes:

• abandoning the convergence criteria, which require deficits to be less than 3% of GDP

• replacing austerity with a growth strategy, supported by a solidarity fund for stabilisation

• dismantling a crisis-prone system whereby countries must borrow in a currency not under their control, and relying instead on Eurobonds or some similar mechanism

• better burden-sharing during adjustment, with countries running current-account surpluses committing to raise wages and increase fiscal spending, thereby ensuring that their prices increase faster than those in the countries with current-account deficits;

• changing the mandate of the European Central Bank, which focuses only on inflation, unlike the US Federal Reserve, which takes into account employment, growth, and stability as well

• establishing common deposit insurance, which would prevent money from fleeing poorly performing countries, and other elements of a “banking union”

• and encouraging, rather than forbidding, industrial policies designed to ensure that the eurozone’s laggards can catch up with its leaders.

From an economic perspective, these changes are small; but today’s eurozone leadership may lack the political will to carry them out. That doesn’t change the basic fact that the current halfway house is untenable. A system intended to promote prosperity and further integration has been having just the opposite effect. An amicable divorce would be better than the current stalemate.

Of course, every divorce is costly; but muddling through would be even more costly. As we’ve already seen this summer in the United Kingdom, if European leaders can’t or won’t make the hard decisions, European voters will make the decisions for them – and the leaders may not be happy with the results.

To say that the eurozone has not been performing well since the 2008 crisis is an understatement. Its member countries have done more poorly than the European Union countries outside the eurozone, and much more poorly than the United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis.

The worst-performing eurozone countries are mired in depression or deep recession; their condition – think of Greece – is worse in many ways than what economies suffered during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The best-performing eurozone members, such as Germany, look good, but only in comparison; and their growth model is partly based on beggar-thy-neighbour policies, whereby success comes at the expense of erstwhile “partners”.

Four types of explanation have been advanced to explain this state of affairs.Germany likes to blame the victim, pointing to Greece’s profligacy and the debt and deficits elsewhere. But this puts the cart before the horse: Spain and Ireland had surpluses and low debt-to-GDP ratios before the euro crisis. So the crisis caused the deficits and debts, not the other way around.

Deficit fetishism is, no doubt, part of Europe’s problems. Finland, too, has been having trouble adjusting to the multiple shocks it has confronted, with GDP in 2015 around 5.5% below its 2008 peak.

Other “blame the victim” critics cite the welfare state and excessive labour-market protections as the cause of the eurozone’s malaise. Yet some of Europe’s best-performing countries, such as Sweden and Norway, have the strongest welfare states and labour-market protections.

Many of the countries now performing poorly were doing very well – above the European average – before the euro was introduced. Their decline did not result from some sudden change in their labour laws, or from an epidemic of laziness in the crisis countries. What changed was the currency arrangement.

The second type of explanation amounts to a wish that Europe had better leaders, men and women who understood economics better and implemented better policies. Flawed policies – not just austerity, but also misguided so-called structural reforms, which widened inequality and thus further weakened overall demand and potential growth – have undoubtedly made matters worse.

But the eurozone was a political arrangement, in which it was inevitable that Germany’s voice would be loud. Anyone who has dealt with German policymakers over the past third of a century should have known in advance the likely result. Most important, given the available tools, not even the most brilliant economic tsar could not have made the eurozone prosper.

The third set of reasons for the eurozone’s poor performance is a broader rightwing critique of the EU, centred on the eurocrats’ penchant for stifling, innovation-inhibiting regulations. This critique, too, misses the mark. The eurocrats, like labour laws or the welfare state, didn’t suddenly change in 1999, with the creation of the fixed exchange-rate system, or in 2008, with the beginning of the crisis. More fundamentally, what matters is the standard of living, the quality of life. Anyone who denies how much better off we in the west are with our stiflingly clean air and water should visit Beijing.

That leaves the fourth explanation: the euro is more to blame than the policies and structures of individual countries. The euro was flawed at birth. Even the best policymakers the world has ever seen could not have made it work. The eurozone’s structure imposed the kind of rigidity associated with the gold standard. The single currency took away its members’ most important mechanism for adjustment – the exchange rate – and the eurozone circumscribed monetary and fiscal policy.

In response to asymmetric shocks and divergences in productivity, there would have to be adjustments in the real (inflation-adjusted) exchange rate, meaning that prices in the eurozone periphery would have to fall relative to Germany and northern Europe. But, with Germany adamant about inflation – its prices have been stagnant – the adjustment could be accomplished only through wrenching deflation elsewhere. Typically, this meant painful unemployment and weakening unions; the eurozone’s poorest countries, and especially the workers within them, bore the brunt of the adjustment burden. So the plan to spur convergence among eurozone countries failed miserably, with disparities between and within countries growing.

This system cannot and will not work in the long run: democratic politics ensures its failure. Only by changing the eurozone’s rules and institutions can the euro be made to work. This will require seven changes:

• abandoning the convergence criteria, which require deficits to be less than 3% of GDP

• replacing austerity with a growth strategy, supported by a solidarity fund for stabilisation

• dismantling a crisis-prone system whereby countries must borrow in a currency not under their control, and relying instead on Eurobonds or some similar mechanism

• better burden-sharing during adjustment, with countries running current-account surpluses committing to raise wages and increase fiscal spending, thereby ensuring that their prices increase faster than those in the countries with current-account deficits;

• changing the mandate of the European Central Bank, which focuses only on inflation, unlike the US Federal Reserve, which takes into account employment, growth, and stability as well

• establishing common deposit insurance, which would prevent money from fleeing poorly performing countries, and other elements of a “banking union”

• and encouraging, rather than forbidding, industrial policies designed to ensure that the eurozone’s laggards can catch up with its leaders.

From an economic perspective, these changes are small; but today’s eurozone leadership may lack the political will to carry them out. That doesn’t change the basic fact that the current halfway house is untenable. A system intended to promote prosperity and further integration has been having just the opposite effect. An amicable divorce would be better than the current stalemate.

Of course, every divorce is costly; but muddling through would be even more costly. As we’ve already seen this summer in the United Kingdom, if European leaders can’t or won’t make the hard decisions, European voters will make the decisions for them – and the leaders may not be happy with the results.

Sunday 21 August 2016

We won't trigger Article 50 until after 2017 – and that means Brexit may never happen at all

Dennis MacShane in The Independent

It is now eight weeks since we voted to leave the EU but it may be at least eight years before the UK is fully and totally out of Europe– if we finally leave at all. After a post-truth Brexit campaign, now the era of truth is dawning in Downing Street and they are discovering there was never any work completed by the Brexit team on what the costs of leaving the EU would be and how precisely it would be done.

The new Prime Minister, Theresa May, who is coldly pragmatic, has given the three Musketeers of Brexit – Boris Johnson, Liam Fox and David Davis – the task of getting us out of Europe as painlessly and quickly as possible. They are finding out that their two decades of demagogic condemnation of the EU and all its works is no preparation at all for turning Brexit into reality. Instead, there is the surreal sight of Liam Fox writing a letter saying that half the Foreign Office staff and responsibilities should be placed under his control. Ever since it was set up after Britain lost America at the end of the 18th century, the Foreign Office has been seeing off raids on its territory like these.

Having been told that leaving the EU would reduce bureaucracy and costs, there is the bizarre sight of Whitehall recruiters hiring lawyers expert in EU law on £5,000 a day and consultants from KPMG and Ernst and Young on £1,000 a day. The extra cost of negotiating Brexit is reckoned to cost £5bn – which taxpayers will have to pay for.

Fox has a name for unforced errors, as his abrupt dismissal as Defence Secretary in 2011 showed. He is finding out from the US Trade Secretary, and every other minister responsible for trade around the world, that no-one will talk to the UK about trade deals until we are completely outside the EU.

For years the Europhobes told us that the world would be queuing up to sign trade deals with Britain once we were out of Europe. Now Fox is discovering that it is illegal under World Trade Organisation rules to start negotiations with the UK as the EU has sole and exclusive responsibility for speaking for its member states on major trade matters.

Of course countries can negotiate small market openings. Spain has spent eight years negotiating a deal to export plums to China. The UK has spent just as long trying to get India to lift its 150 per cent tariff on Scotch whisky – so far, without success. The Indians are willing to let Scotch be imported duty-free but in exchange they want visa-free access for Indians to come to the UK. Over to Dr Fox to solve that conundrum.

When she was Home Secretary, Theresa May tried to abolish visa-free travel arrangements with Brazil, but was slapped down by David Cameron who judged the good relations with Brazil was worth the risk of some over-staying by Brazilians who came to London and then disappeared into the black labour market. The same dilemma faces UK exporters who have been told by all EU leaders, not just the wicked Eurocrats, but nationally elected leaders in Germany and France that there is no question of having access to the EU Single Market for 500 million middle class consumers without allowing those consumers the right to travel, live and work – the same rights that more than a million Brits in Spain enjoy too.

No-one in Europe wants to ”punish” Britain but no EU leader dare deny his or her own citizens the rights that Brits take for granted in order to give the UK a special privileged status.

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has sensibly said that there is no point in beginning the initial withdrawal negotiations – the so-called 'Article 50 procedure' – until there is clarity on who will be in charge of Europe. In 2017 there are elections in France likely to produce a new president next May and right-wing challengers have called for the relocation of the Calais frontier to UK territory. Angela Merkel will have done 12 years as German Chancellor at the time of the federal elections in September 2017 and may decide to stand down rather than go on and on and on to the kind of unhappy career end of Helmut Kohl.

But Khan, a shrewd EU watcher, is right to say that inserting a rushed UK withdrawal into a crucial election year in both France and Germany is not smart.

He also has to speak for London and the $120tn volume of business in trading and clearing euros, which only takes place in London because we are in the EU. London is home to 350,000 French citizens alone, as well as hundreds of thousands other European professionals, and removing their right to live and work freely in the UK will send a disastrous signal around the world that London is no longer Europe’s hub for financial transactions.

In any event, Article 50 negotiations are not even foreplay to the main event. They only cover how to share out between Brussels and London the responsibility for paying the pensions of Brits who work for the EU and will now be dismissed, as well as existing retirees like Stanley Johnson, father of Brexiteer Boris.