At around 8pm on Sunday 29 January, a young man walked into a mosque in the Sainte-Foy neighbourhood of Quebec City and opened fire on worshippers with a 9mm handgun. The imam had just finished leading the congregation in prayer when the intruder started shooting at them. He killed six and injured 19 more. The dead included an IT specialist employed by the city council, a grocer, and a science professor.

The suspect, Alexandre Bissonnette, a 27-year-old student, has been charged with six counts of murder, though not terrorism. Within hours of the attack, Ralph Goodale, the Canadian minister for public safety, described the killer as “a lone wolf”. His statement was rapidly picked up by the world’s media.

Goodale’s statement came as no surprise. In early 2017, well into the second decade of the most intense wave of international terrorism since the 1970s, the lone wolf has, for many observers, come to represent the most urgent security threat faced by the west. The term, which describes an individual actor who strikes alone and is not affiliated with any larger group, is now widely used by politicians, journalists, security officials and the general public. It is used for Islamic militant attackers and, as the shooting in Quebec shows, for killers with other ideological motivations. Within hours of the news breaking of an attack on pedestrians and a policeman in central London last week, it was used to describe the 52-year-old British convert responsible. Yet few beyond the esoteric world of terrorism analysis appear to give this almost ubiquitous term much thought.

Terrorism has changed dramatically in recent years. Attacks by groups with defined chains of command have become rarer, as the prevalence of terrorist networks, autonomous cells, and, in rare cases, individuals, has grown. This evolution has prompted a search for a new vocabulary, as it should. The label that seems to have been decided on is “lone wolves”. They are, we have been repeatedly told, “Terror enemy No 1”.

Yet using the term as liberally as we do is a mistake. Labels frame the way we see the world, and thus influence attitudes and eventually policies. Using the wrong words to describe problems that we need to understand distorts public perceptions, as well as the decisions taken by our leaders. Lazy talk of “lone wolves” obscures the real nature of the threat against us, and makes us all less safe.

The image of the lone wolf who splits from the pack has been a staple of popular culture since the 19th century, cropping up in stories about empire and exploration from British India to the wild west. From 1914 onwards, the term was popularised by a bestselling series of crime novels and films centred upon a criminal-turned-good-guy nicknamed Lone Wolf. Around that time, it also began to appear in US law enforcement circles and newspapers. In April 1925, the New York Times reported on a man who “assumed the title of ‘Lone Wolf’”, who terrorised women in a Boston apartment building. But it would be many decades before the term came to be associated with terrorism.

In the 1960s and 1970s, waves of rightwing and leftwing terrorism struck the US and western Europe. It was often hard to tell who was responsible: hierarchical groups, diffuse networks or individuals effectively operating alone. Still, the majority of actors belonged to organisations modelled on existing military or revolutionary groups. Lone actors were seen as eccentric oddities, not as the primary threat.

The modern concept of lone-wolf terrorism was developed by rightwing extremists in the US. In 1983, at a time when far-right organisations were coming under immense pressure from the FBI, a white nationalist named Louis Beam published a manifesto that called for “leaderless resistance” to the US government. Beam, who was a member of both the Ku Klux Klan and the Aryan Nations group, was not the first extremist to elaborate the strategy, but he is one of the best known. He told his followers that only a movement based on “very small or even one-man cells of resistance … could combat the most powerful government on earth”.

Terrorism has changed dramatically in recent years. Attacks by groups with defined chains of command have become rarer, as the prevalence of terrorist networks, autonomous cells, and, in rare cases, individuals, has grown. This evolution has prompted a search for a new vocabulary, as it should. The label that seems to have been decided on is “lone wolves”. They are, we have been repeatedly told, “Terror enemy No 1”.

Yet using the term as liberally as we do is a mistake. Labels frame the way we see the world, and thus influence attitudes and eventually policies. Using the wrong words to describe problems that we need to understand distorts public perceptions, as well as the decisions taken by our leaders. Lazy talk of “lone wolves” obscures the real nature of the threat against us, and makes us all less safe.

The image of the lone wolf who splits from the pack has been a staple of popular culture since the 19th century, cropping up in stories about empire and exploration from British India to the wild west. From 1914 onwards, the term was popularised by a bestselling series of crime novels and films centred upon a criminal-turned-good-guy nicknamed Lone Wolf. Around that time, it also began to appear in US law enforcement circles and newspapers. In April 1925, the New York Times reported on a man who “assumed the title of ‘Lone Wolf’”, who terrorised women in a Boston apartment building. But it would be many decades before the term came to be associated with terrorism.

In the 1960s and 1970s, waves of rightwing and leftwing terrorism struck the US and western Europe. It was often hard to tell who was responsible: hierarchical groups, diffuse networks or individuals effectively operating alone. Still, the majority of actors belonged to organisations modelled on existing military or revolutionary groups. Lone actors were seen as eccentric oddities, not as the primary threat.

The modern concept of lone-wolf terrorism was developed by rightwing extremists in the US. In 1983, at a time when far-right organisations were coming under immense pressure from the FBI, a white nationalist named Louis Beam published a manifesto that called for “leaderless resistance” to the US government. Beam, who was a member of both the Ku Klux Klan and the Aryan Nations group, was not the first extremist to elaborate the strategy, but he is one of the best known. He told his followers that only a movement based on “very small or even one-man cells of resistance … could combat the most powerful government on earth”.

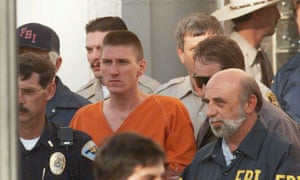

Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh leaves court, 1995. Photograph: David Longstreath/AP

Experts still argue over how much impact the thinking of Beam and other like-minded white supremacists had on rightwing extremists in the US. Timothy McVeigh, who killed 168 people with a bomb directed at a government office in Oklahoma City in 1995, is sometimes cited as an example of someone inspired by their ideas. But McVeigh had told others of his plans, had an accomplice, and had been involved for many years with rightwing militia groups. McVeigh may have thought of himself as a lone wolf, but he was not one.

One far-right figure who made explicit use of the term lone wolf was Tom Metzger, the leader of White Aryan Resistance, a group based in Indiana. Metzger is thought to have authored, or at least published on his website, a call to arms entitled “Laws for the Lone Wolf”. “I am preparing for the coming War. I am ready when the line is crossed … I am the underground Insurgent fighter and independent. I am in your neighborhoods, schools, police departments, bars, coffee shops, malls, etc. I am, The Lone Wolf!,” it reads.

From the mid-1990s onwards, as Metzger’s ideas began to spread, the number of hate crimes committed by self-styled “leaderless” rightwing extremists rose. In 1998, the FBI launched Operation Lone Wolf against a small group of white supremacists on the US west coast. A year later, Alex Curtis, a young, influential rightwing extremist and protege of Metzger, told his hundreds of followers in an email that “lone wolves who are smart and commit to action in a cold-mannered way can accomplish virtually any task before them ... We are already too far along to try to educate the white masses and we cannot worry about [their] reaction to lone wolf/small cell strikes.”

The same year, the New York Times published a long article on the new threat headlined “New Face of Terror Crimes: ‘Lone Wolf’ Weaned on Hate”. This seems to have been the moment when the idea of terrorist “lone wolves” began to migrate from rightwing extremist circles, and the law enforcement officials monitoring them, to the mainstream. In court on charges of hate crimes in 2000, Curtis was described by prosecutors as an advocate of lone-wolf terrorism.

When, more than a decade later, the term finally became a part of the everyday vocabulary of millions of people, it was in a dramatically different context.

After 9/11, lone-wolf terrorism suddenly seemed like a distraction from more serious threats. The 19 men who carried out the attacks were jihadis who had been hand picked, trained, equipped and funded by Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaida, and a small group of close associates.

Although 9/11 was far from a typical terrorist attack, it quickly came to dominate thinking about the threat from Islamic militants. Security services built up organograms of terrorist groups. Analysts focused on individual terrorists only insofar as they were connected to bigger entities. Personal relations – particularly friendships based on shared ambitions and battlefield experiences, as well as tribal or familial links – were mistaken for institutional ones, formally connecting individuals to organisations and placing them under a chain of command.

As the 2000s drew to a close, attacks perpetrated by people who seemed to be acting alone began to outnumber all others

This approach suited the institutions and individuals tasked with carrying out the “war on terror”. For prosecutors, who were working with outdated legislation, proving membership of a terrorist group was often the only way to secure convictions of individuals planning violence. For a number of governments around the world – Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Egypt – linking attacks on their soil to “al-Qaida” became a way to shift attention away from their own brutality, corruption and incompetence, and to gain diplomatic or material benefits from Washington. For some officials in Washington, linking terrorist attacks to “state-sponsored” groups became a convenient way to justify policies, such as the continuing isolation of Iran, or military interventions such as the invasion of Iraq. For many analysts and policymakers, who were heavily influenced by the conventional wisdom on terrorism inherited from the cold war, thinking in terms of hierarchical groups and state sponsors was comfortably familiar.

A final factor was more subtle. Attributing the new wave of violence to a single group not only obscured the deep, complex and troubling roots of Islamic militancy but also suggested the threat it posed would end when al-Qaida was finally eliminated. This was reassuring, both for decision-makers and the public.

By the middle of the decade, it was clear that this analysis was inadequate. Bombs in Bali, Istanbul and Mombasa were the work of centrally organised attackers, but the 2004 attack on trains in Madrid had been executed by a small network only tenuously connected to the al-Qaida senior leadership 4,000 miles away. For every operation like the 2005 bombings in London – which was close to the model established by the 9/11 attacks – there were more attacks that didn’t seem to have any direct link to Bin Laden, even if they might have been inspired by his ideology. There was growing evidence that the threat from Islamic militancy was evolving into something different, something closer to the “leaderless resistance” promoted by white supremacists two decades earlier.

As the 2000s drew to a close, attacks perpetrated by people who seemed to be acting alone began to outnumber all others. These events were less deadly than the spectacular strikes of a few years earlier, but the trend was alarming. In the UK in 2008, a convert to Islam with mental health problems attempted to blow up a restaurant in Exeter, though he injured no one but himself. In 2009, a US army major shot 13 dead in Fort Hood, Texas. In 2010, a female student stabbed an MPin London. None appeared, initially, to have any broader connections to the global jihadi movement.

Experts still argue over how much impact the thinking of Beam and other like-minded white supremacists had on rightwing extremists in the US. Timothy McVeigh, who killed 168 people with a bomb directed at a government office in Oklahoma City in 1995, is sometimes cited as an example of someone inspired by their ideas. But McVeigh had told others of his plans, had an accomplice, and had been involved for many years with rightwing militia groups. McVeigh may have thought of himself as a lone wolf, but he was not one.

One far-right figure who made explicit use of the term lone wolf was Tom Metzger, the leader of White Aryan Resistance, a group based in Indiana. Metzger is thought to have authored, or at least published on his website, a call to arms entitled “Laws for the Lone Wolf”. “I am preparing for the coming War. I am ready when the line is crossed … I am the underground Insurgent fighter and independent. I am in your neighborhoods, schools, police departments, bars, coffee shops, malls, etc. I am, The Lone Wolf!,” it reads.

From the mid-1990s onwards, as Metzger’s ideas began to spread, the number of hate crimes committed by self-styled “leaderless” rightwing extremists rose. In 1998, the FBI launched Operation Lone Wolf against a small group of white supremacists on the US west coast. A year later, Alex Curtis, a young, influential rightwing extremist and protege of Metzger, told his hundreds of followers in an email that “lone wolves who are smart and commit to action in a cold-mannered way can accomplish virtually any task before them ... We are already too far along to try to educate the white masses and we cannot worry about [their] reaction to lone wolf/small cell strikes.”

The same year, the New York Times published a long article on the new threat headlined “New Face of Terror Crimes: ‘Lone Wolf’ Weaned on Hate”. This seems to have been the moment when the idea of terrorist “lone wolves” began to migrate from rightwing extremist circles, and the law enforcement officials monitoring them, to the mainstream. In court on charges of hate crimes in 2000, Curtis was described by prosecutors as an advocate of lone-wolf terrorism.

When, more than a decade later, the term finally became a part of the everyday vocabulary of millions of people, it was in a dramatically different context.

After 9/11, lone-wolf terrorism suddenly seemed like a distraction from more serious threats. The 19 men who carried out the attacks were jihadis who had been hand picked, trained, equipped and funded by Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaida, and a small group of close associates.

Although 9/11 was far from a typical terrorist attack, it quickly came to dominate thinking about the threat from Islamic militants. Security services built up organograms of terrorist groups. Analysts focused on individual terrorists only insofar as they were connected to bigger entities. Personal relations – particularly friendships based on shared ambitions and battlefield experiences, as well as tribal or familial links – were mistaken for institutional ones, formally connecting individuals to organisations and placing them under a chain of command.

As the 2000s drew to a close, attacks perpetrated by people who seemed to be acting alone began to outnumber all others

This approach suited the institutions and individuals tasked with carrying out the “war on terror”. For prosecutors, who were working with outdated legislation, proving membership of a terrorist group was often the only way to secure convictions of individuals planning violence. For a number of governments around the world – Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Egypt – linking attacks on their soil to “al-Qaida” became a way to shift attention away from their own brutality, corruption and incompetence, and to gain diplomatic or material benefits from Washington. For some officials in Washington, linking terrorist attacks to “state-sponsored” groups became a convenient way to justify policies, such as the continuing isolation of Iran, or military interventions such as the invasion of Iraq. For many analysts and policymakers, who were heavily influenced by the conventional wisdom on terrorism inherited from the cold war, thinking in terms of hierarchical groups and state sponsors was comfortably familiar.

A final factor was more subtle. Attributing the new wave of violence to a single group not only obscured the deep, complex and troubling roots of Islamic militancy but also suggested the threat it posed would end when al-Qaida was finally eliminated. This was reassuring, both for decision-makers and the public.

By the middle of the decade, it was clear that this analysis was inadequate. Bombs in Bali, Istanbul and Mombasa were the work of centrally organised attackers, but the 2004 attack on trains in Madrid had been executed by a small network only tenuously connected to the al-Qaida senior leadership 4,000 miles away. For every operation like the 2005 bombings in London – which was close to the model established by the 9/11 attacks – there were more attacks that didn’t seem to have any direct link to Bin Laden, even if they might have been inspired by his ideology. There was growing evidence that the threat from Islamic militancy was evolving into something different, something closer to the “leaderless resistance” promoted by white supremacists two decades earlier.

As the 2000s drew to a close, attacks perpetrated by people who seemed to be acting alone began to outnumber all others. These events were less deadly than the spectacular strikes of a few years earlier, but the trend was alarming. In the UK in 2008, a convert to Islam with mental health problems attempted to blow up a restaurant in Exeter, though he injured no one but himself. In 2009, a US army major shot 13 dead in Fort Hood, Texas. In 2010, a female student stabbed an MPin London. None appeared, initially, to have any broader connections to the global jihadi movement.

In an attempt to understand how this new threat had developed, analysts raked through the growing body of texts posted online by jihadi thinkers. It seemed that one strategist had been particularly influential: a Syrian called Mustafa Setmariam Nasar, better known as Abu Musab al-Suri. In 2004, in a sprawling set of writings posted on an extremist website, Nasar had laid out a new strategy that was remarkably similar to “leaderless resistance”, although there is no evidence that he knew of the thinking of men such as Beam or Metzger. Nasar’s maxim was “Principles, not organisations”. He envisaged individual attackers and cells, guided by texts published online, striking targets across the world.

Having identified this new threat, security officials, journalists and policymakers needed a new vocabulary to describe it. The rise of the term lone wolf wasn’t wholly unprecedented. In the aftermath of 9/11, the US had passed anti-terror legislation that included a so-called “lone wolf provision”. This made it possible to pursue terrorists who were members of groups based abroad but who were acting alone in the US. Yet this provision conformed to the prevailing idea that all terrorists belonged to bigger groups and acted on orders from their superiors. The stereotype of the lone wolf terrorist that dominates today’s media landscape was not yet fully formed.

It is hard to be exact about when things changed. By around 2006, a small number of analysts had begun to refer to lone-wolf attacks in the context of Islamic militancy, and Israeli officials were using the term to describe attacks by apparently solitary Palestinian attackers. Yet these were outliers. In researching this article, I called eight counter-terrorism officials active over the last decade to ask them when they had first heard references to lone-wolf terrorism. One said around 2008, three said 2009, three 2010 and one around 2011. “The expression is what gave the concept traction,” Richard Barrett, who held senior counter-terrorist positions in MI6, the British overseas intelligence service, and the UN through the period, told me. Before the rise of the lone wolf, security officials used phrases – all equally flawed – such as “homegrowns”, “cleanskins”, “freelancers” or simply “unaffiliated”.

As successive jihadi plots were uncovered that did not appear to be linked to al-Qaida or other such groups, the term became more common. Between 2009 and 2012 it appears in around 300 articles in major English-language news publications each year, according the professional cuttings search engine Lexis Nexis. Since then, the term has become ubiquitous. In the 12 months before the London attack last week, the number of references to “lone wolves” exceeded the total of those over the previous three years, topping 1,000.

Lone wolves are now apparently everywhere, stalking our streets, schools and airports. Yet, as with the tendency to attribute all terrorist attacks to al-Qaida a decade earlier, this is a dangerous simplification.

In March 2012, a 23-year-old petty criminal named Mohamed Merah went on a shooting spree – a series of three attacks over a period of nine days – in south-west France, killing seven people. Bernard Squarcini, head of the French domestic intelligence service, described Merah as a lone wolf. So did the interior ministry spokesman, and, inevitably, many journalists. A year later, Lee Rigby, an off-duty soldier, was run over and hacked to death in London. Once again, the two attackers were dubbed lone wolves by officials and the media. So, too, were Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the brothers who bombed the Boston Marathon in 2013. The same label has been applied to more recent attackers, including the men who drove vehicles into crowds in Nice and Berlin last year, and in London last week.

Having identified this new threat, security officials, journalists and policymakers needed a new vocabulary to describe it. The rise of the term lone wolf wasn’t wholly unprecedented. In the aftermath of 9/11, the US had passed anti-terror legislation that included a so-called “lone wolf provision”. This made it possible to pursue terrorists who were members of groups based abroad but who were acting alone in the US. Yet this provision conformed to the prevailing idea that all terrorists belonged to bigger groups and acted on orders from their superiors. The stereotype of the lone wolf terrorist that dominates today’s media landscape was not yet fully formed.

It is hard to be exact about when things changed. By around 2006, a small number of analysts had begun to refer to lone-wolf attacks in the context of Islamic militancy, and Israeli officials were using the term to describe attacks by apparently solitary Palestinian attackers. Yet these were outliers. In researching this article, I called eight counter-terrorism officials active over the last decade to ask them when they had first heard references to lone-wolf terrorism. One said around 2008, three said 2009, three 2010 and one around 2011. “The expression is what gave the concept traction,” Richard Barrett, who held senior counter-terrorist positions in MI6, the British overseas intelligence service, and the UN through the period, told me. Before the rise of the lone wolf, security officials used phrases – all equally flawed – such as “homegrowns”, “cleanskins”, “freelancers” or simply “unaffiliated”.

As successive jihadi plots were uncovered that did not appear to be linked to al-Qaida or other such groups, the term became more common. Between 2009 and 2012 it appears in around 300 articles in major English-language news publications each year, according the professional cuttings search engine Lexis Nexis. Since then, the term has become ubiquitous. In the 12 months before the London attack last week, the number of references to “lone wolves” exceeded the total of those over the previous three years, topping 1,000.

Lone wolves are now apparently everywhere, stalking our streets, schools and airports. Yet, as with the tendency to attribute all terrorist attacks to al-Qaida a decade earlier, this is a dangerous simplification.

In March 2012, a 23-year-old petty criminal named Mohamed Merah went on a shooting spree – a series of three attacks over a period of nine days – in south-west France, killing seven people. Bernard Squarcini, head of the French domestic intelligence service, described Merah as a lone wolf. So did the interior ministry spokesman, and, inevitably, many journalists. A year later, Lee Rigby, an off-duty soldier, was run over and hacked to death in London. Once again, the two attackers were dubbed lone wolves by officials and the media. So, too, were Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the brothers who bombed the Boston Marathon in 2013. The same label has been applied to more recent attackers, including the men who drove vehicles into crowds in Nice and Berlin last year, and in London last week.

The Boston Marathon bombing carried out by Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev in 2013. Photograph: Dan Lampariello/Reuters

One problem facing security services, politicians and the media is that instant analysis is difficult. It takes months to unravel the truth behind a major, or even minor, terrorist operation. The demand for information from a frightened public, relayed by a febrile news media, is intense. People seek quick, familiar explanations.

Yet many of the attacks that have been confidently identified as lone-wolf operations have turned out to be nothing of the sort. Very often, terrorists who are initially labelled lone wolves, have active links to established groups such as Islamic State and al-Qaida. Merah, for instance, had recently travelled to Pakistan and been trained, albeit cursorily, by a jihadi group allied with al-Qaida. Merah was also linked to a network of local extremists, some of whom went on to carry out attacks in Libya, Iraq and Syria. Bernard Cazeneuve, who was then the French interior minister, later agreed that calling Merah a lone wolf had been a mistake.

If, in cases such as Merah’s, the label of lone wolf is plainly incorrect, there are other, more subtle cases where it is still highly misleading. Another category of attackers, for instance, are those who strike alone, without guidance from formal terrorist organisations, but who have had face-to-face contact with loose networks of people who share extremist beliefs. The Exeter restaurant bomber, dismissed as an unstable loner, was actually in contact with a circle of local militant sympathisers before his attack. (They have never been identified.) The killers of Lee Rigby had been on the periphery of extremist movements in the UK for years, appearing at rallies of groups such as the now proscribed al-Muhajiroun, run by Anjem Choudary, a preacher convicted of terrorist offences in 2016 who is reported to have “inspired” up to 100 British militants.

A third category is made up of attackers who strike alone, after having had close contact online, rather than face-to-face, with extremist groups or individuals. A wave of attackers in France last year were, at first, wrongly seen as lone wolves “inspired” rather than commissioned by Isis. It soon emerged that the individuals involved, such as the two teenagers who killed a priest in front of his congregation in Normandy, had been recruited online by a senior Isis militant. In three recent incidents in Germany, all initially dubbed “lone-wolf attacks”, Isis militants actually used messaging apps to direct recruits in the minutes before they attacked. “Pray that I become a martyr,” one attacker who assaulted passengers on a train with an axe and knife told his interlocutor. “I am now waiting for the train.” Then: “I am starting now.”

Very often, what appear to be the clearest lone-wolf cases are revealed to be more complex. Even the strange case of the man who killed 86 people with a truck in Nice in July 2016 – with his background of alcohol abuse, casual sex and lack of apparent interest in religion or radical ideologies – may not be a true lone wolf. Eight of his friends and associates have been arrested and police are investigating his potential links to a broader network.

What research does show is that we may be more likely to find lone wolves among far-right extremists than among their jihadi counterparts. Though even in those cases, the term still conceals more than it reveals.

The murder of the Labour MP Jo Cox, days before the EU referendum, by a 52-year-old called Thomas Mair, was the culmination of a steady intensification of rightwing extremist violence in the UK that had been largely ignored by the media and policymakers. According to police, on several occasions attackers came close to causing more casualties in a single operation than jihadis had ever inflicted. The closest call came in 2013 when Pavlo Lapshyn, a Ukrainian PhD student in the UK, planted a bomb outside a mosque in Tipton, West Midlands. Fortunately, Lapshyn had got his timings wrong and the congregation had yet to gather when the device exploded. Embedded in the trunks of trees surrounding the building, police found some of the 100 nails Lapshyn had added to the bomb to make it more lethal.

Lapshyn was a recent arrival, but the UK has produced numerous homegrown far-right extremists in recent years. One was Martyn Gilleard, who was sentenced to 16 years for terrorism and child pornography offences in 2008. When officers searched his home in Goole, East Yorkshire, they found knives, guns, machetes, swords, axes, bullets and four nail bombs. A year later, Ian Davison became the first Briton convicted under new legislation dealing with the production of chemical weapons. Davison was sentenced to 10 years in prison for manufacturing ricin, a lethal biological poison made from castor beans. His aim, the court heard, was “the creation of an international Aryan group who would establish white supremacy in white countries”.

Lapshyn, Gilleard and Davison were each described as lone wolves by police officers, judges and journalists. Yet even a cursory survey of their individual stories undermines this description. Gilleard was the local branch organiser of a neo-Nazi group, while Davison founded the Aryan Strike Force, the members of which went on training days in Cumbria where they flew swastika flags.

Thomas Mair, who was also widely described as a lone wolf, does appear to have been an authentic loner, yet his involvement in rightwing extremism goes back decades. In May 1999, the National Alliance, a white-supremacist organisation in West Virginia, sent Mair manuals that explained how to construct bombs and assemble homemade pistols. Seventeen years later, when police raided his home after the murder, they found stacks of far-right literature, Nazi memorabilia and cuttings on Anders Breivik, the Norwegian terrorist who murdered 77 people in 2011.

A government building in Oslo bombed by Anders Breivik, July 2011. Photograph: Scanpix/Reuters

Even Breivik himself, who has been called “the deadliest lone-wolf attacker in [Europe’s] history”, was not a true lone wolf. Prior to his arrest, Breivik had long been in contact with far-right organisations. A member of the English Defence League told the Telegraph that Breivik had been in regular contact with its members via Facebook, and had a “hypnotic” effect on them.

If such facts fit awkwardly with the commonly accepted idea of the lone wolf, they fit better with academic research that has shown that very few violent extremists who launch attacks act without letting others know what they may be planning. In the late 1990s, after realising that in most instances school shooters would reveal their intentions to close associates before acting, the FBI began to talk about “leakage” of critical information. By 2009, it had extended the concept to terrorist attacks, and found that “leakage” was identifiable in more than four-fifths of 80 ongoing cases they were investigating. Of these leaks, 95% were to friends, close relatives or authority figures.

More recent research has underlined the garrulous nature of violent extremists. In 2013, researchers at Pennsylvania State University examined the interactions of 119 lone-wolf terrorists from a wide variety of ideological and faith backgrounds. The academics found that, even though the terrorists launched their attacks alone, in 79% of cases others were aware of the individual’s extremist ideology, and in 64% of cases family and friends were aware of the individual’s intent to engage in terrorism-related activity. Another more recent survey found that 45% of Islamic militant cases talked about their inspiration and possible actions with family and friends. While only 18% of rightwing counterparts did, they were much more likely to “post telling indicators” on the internet.

Few extremists remain without human contact, even if that contact is only found online. Last year, a team at the University of Miami studied 196 pro-Isis groupsoperating on social media during the first eight months of 2015. These groups had a combined total of more than 100,000 members. Researchers also found that pro-Isis individuals who were not in a group – who they dubbed “online ‘lone wolf’ actors” – had either recently been in a group or soon went on to join one.

Any terrorist, however socially or physically isolated, is still part of a broader movement

There is a much broader point here. Any terrorist, however socially or physically isolated, is still part of a broader movement. The lengthy manifesto that Breivik published hours before he started killing drew heavily on a dense ecosystem of far-right blogs, websites and writers. His ideas on strategy drew directly from the “leaderless resistance” school of Beam and others. Even his musical tastes were shaped by his ideology. He was, for example, a fan of Saga, a Swedish white nationalist singer, whose lyrics include lines about “The greatest race to ever walk the earth … betrayed”.

It is little different for Islamic militants, who emerge as often from the fertile and desperately depressing world of online jihadism – with its execution videos, mythologised history, selectively read religious texts and Photoshopped pictures of alleged atrocities against Muslims – as from organised groups that meet in person.

Terrorist violence of all kinds is directed against specific targets. These are not selected at random, nor are such attacks the products of a fevered and irrational imagination operating in complete isolation.

Just like the old idea that a single organisation, al-Qaida, was responsible for all Islamic terrorism, the rise of the lone-wolf paradigm is convenient for many different actors. First, there are the terrorists themselves. The notion that we are surrounded by anonymous lone wolves poised to strike at any time inspires fear and polarises the public. What could be more alarming and divisive than the idea that someone nearby – perhaps a colleague, a neighbour, a fellow commuter – might secretly be a lone wolf?

Terrorist groups also need to work constantly to motivate their activists. The idea of “lone wolves” invests murderous attackers with a special status, even glamour. Breivik, for instance, congratulated himself in his manifesto for becoming a “self-financed and self-indoctrinated single individual attack cell”. Al-Qaida propaganda lauded the 2009 Fort Hood shooter as “a pioneer, a trailblazer, and a role model who has opened a door, lit a path, and shown the way forward for every Muslim who finds himself among the unbelievers”.

The lone-wolf paradigm can be helpful for security services and policymakers, too, since the public assumes that lone wolves are difficult to catch. This would be justified if the popular image of the lone wolf as a solitary actor was accurate. But, as we have seen, this is rarely the case.

Even Breivik himself, who has been called “the deadliest lone-wolf attacker in [Europe’s] history”, was not a true lone wolf. Prior to his arrest, Breivik had long been in contact with far-right organisations. A member of the English Defence League told the Telegraph that Breivik had been in regular contact with its members via Facebook, and had a “hypnotic” effect on them.

If such facts fit awkwardly with the commonly accepted idea of the lone wolf, they fit better with academic research that has shown that very few violent extremists who launch attacks act without letting others know what they may be planning. In the late 1990s, after realising that in most instances school shooters would reveal their intentions to close associates before acting, the FBI began to talk about “leakage” of critical information. By 2009, it had extended the concept to terrorist attacks, and found that “leakage” was identifiable in more than four-fifths of 80 ongoing cases they were investigating. Of these leaks, 95% were to friends, close relatives or authority figures.

More recent research has underlined the garrulous nature of violent extremists. In 2013, researchers at Pennsylvania State University examined the interactions of 119 lone-wolf terrorists from a wide variety of ideological and faith backgrounds. The academics found that, even though the terrorists launched their attacks alone, in 79% of cases others were aware of the individual’s extremist ideology, and in 64% of cases family and friends were aware of the individual’s intent to engage in terrorism-related activity. Another more recent survey found that 45% of Islamic militant cases talked about their inspiration and possible actions with family and friends. While only 18% of rightwing counterparts did, they were much more likely to “post telling indicators” on the internet.

Few extremists remain without human contact, even if that contact is only found online. Last year, a team at the University of Miami studied 196 pro-Isis groupsoperating on social media during the first eight months of 2015. These groups had a combined total of more than 100,000 members. Researchers also found that pro-Isis individuals who were not in a group – who they dubbed “online ‘lone wolf’ actors” – had either recently been in a group or soon went on to join one.

Any terrorist, however socially or physically isolated, is still part of a broader movement

There is a much broader point here. Any terrorist, however socially or physically isolated, is still part of a broader movement. The lengthy manifesto that Breivik published hours before he started killing drew heavily on a dense ecosystem of far-right blogs, websites and writers. His ideas on strategy drew directly from the “leaderless resistance” school of Beam and others. Even his musical tastes were shaped by his ideology. He was, for example, a fan of Saga, a Swedish white nationalist singer, whose lyrics include lines about “The greatest race to ever walk the earth … betrayed”.

It is little different for Islamic militants, who emerge as often from the fertile and desperately depressing world of online jihadism – with its execution videos, mythologised history, selectively read religious texts and Photoshopped pictures of alleged atrocities against Muslims – as from organised groups that meet in person.

Terrorist violence of all kinds is directed against specific targets. These are not selected at random, nor are such attacks the products of a fevered and irrational imagination operating in complete isolation.

Just like the old idea that a single organisation, al-Qaida, was responsible for all Islamic terrorism, the rise of the lone-wolf paradigm is convenient for many different actors. First, there are the terrorists themselves. The notion that we are surrounded by anonymous lone wolves poised to strike at any time inspires fear and polarises the public. What could be more alarming and divisive than the idea that someone nearby – perhaps a colleague, a neighbour, a fellow commuter – might secretly be a lone wolf?

Terrorist groups also need to work constantly to motivate their activists. The idea of “lone wolves” invests murderous attackers with a special status, even glamour. Breivik, for instance, congratulated himself in his manifesto for becoming a “self-financed and self-indoctrinated single individual attack cell”. Al-Qaida propaganda lauded the 2009 Fort Hood shooter as “a pioneer, a trailblazer, and a role model who has opened a door, lit a path, and shown the way forward for every Muslim who finds himself among the unbelievers”.

The lone-wolf paradigm can be helpful for security services and policymakers, too, since the public assumes that lone wolves are difficult to catch. This would be justified if the popular image of the lone wolf as a solitary actor was accurate. But, as we have seen, this is rarely the case.

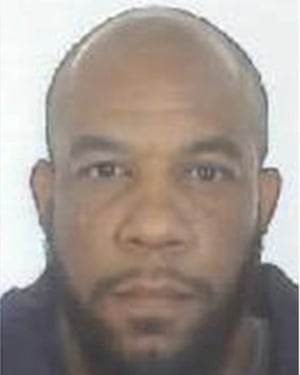

Westminster terrorist Khalid Masood. Photograph: Reuters

The reason that many attacks are not prevented is not because it was impossible to anticipate the perpetrator’s actions, but because someone screwed up. German law enforcement agencies were aware that the man who killed 12 in Berlin before Christmas was an Isis sympathiser and had talked about committing an attack. Repeated attempts to deport him had failed, stymied by bureaucracy, lack of resources and poor case preparation. In Britain, a parliamentary report into the killing of Lee Rigby identified a number of serious delays and potential missed opportunities to prevent it. Khalid Masood, the man who attacked Westminster last week, was identified in 2010 as a potential extremist by MI5.

But perhaps the most disquieting explanation for the ubiquity of the term is that it tells us something we want to believe. Yes, the terrorist threat now appears much more amorphous and unpredictable than ever before. At the same time, the idea that terrorists operate alone allows us to break the link between an act of violence and its ideological hinterland. It implies that the responsibility for an individual’s violent extremism lies solely with the individual themselves.

The truth is much more disturbing. Terrorism is not something you do by yourself, it is highly social. People become interested in ideas, ideologies and activities, even appalling ones, because other people are interested in them.

In his eulogy at the funeral of those killed in the mosque shooting in Quebec, the imam Hassan Guillet spoke of the alleged shooter. Over previous days details had emerged of the young man’s life. “Alexandre [Bissonette], before being a killer, was a victim himself,” said Hassan. “Before he planted his bullets in the heads of his victims, somebody planted ideas more dangerous than the bullets in his head. Unfortunately, day after day, week after week, month after month, certain politicians, and certain reporters and certain media, poisoned our atmosphere.

“We did not want to see it …. because we love this country, we love this society. We wanted our society to be perfect. We were like some parents who, when a neighbour tells them their kid is smoking or taking drugs, answers: ‘I don’t believe it, my child is perfect.’ We don’t want to see it. And we didn’t see it, and it happened.”

“But,” he went on to say, “there was a certain malaise. Let us face it. Alexandre Bissonnette didn’t emerge from a vacuum.”