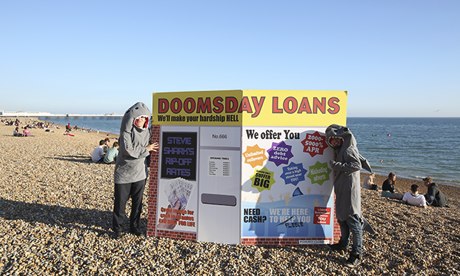

Behind talk of needing to balance the books is a far-reaching project to unleash market forces into all domains of our lives

Illustration by Satoshi Kambayashi

Balancing the books – or counting beans, if you want to be dismissive about it – is what this is all supposed to be about. The cuts in social spending are regrettable, we are told, but they have to be made because the government cannot have more outgoings than its income, as no sensible household should. Didn't Adam Smith, the grandfather of economics, tell us that what "is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarcely be folly in that of a great kingdom"?

The argument for book-balancing has been used even to justify the privatisation of Royal Mail, not least because the usual argument about inefficiency of public enterprises does not apply to it. The sale will increase government revenue and thus reduce budget deficits, it is said. In the same vein, the government has patted itself on the back for selling (and planning to sell) the shares of the bailed-out banks at a profit, further reducing deficits.

Don't be fooled by all the boring language of bookkeeping, however. Behind it lies an ambitious project to restructure British society fundamentally by expanding the domains of our life that are subject to market forces. In the last few years, regulation has been strengthened for the financial sector, although not as much as you would have thought, given the mess that it created. But in almost all other areas of life, the trend has been an unleashing of market forces. And the results have been rather stark – and will become more so, if the project is allowed to continue.

Thanks to cuts in social spending, the disabled and the elderly have had to buy more expensive supports from the market – or, more typically, put up with greater discomfort and indignity. With cuts in unemployment benefit, an increasing number of workers have been forced to accept zero-hour contracts and other employment conditions that are more fitting for developing countries, if not exactly for the Victorian era.

Privatisation and contracting-out of government services have meant that more and more services that used to be provided on the basis of citizenship are now distributed according to how much people can pay. As we have already seen with energy, water and railways, privatisation of "natural monopolies" means higher prices and/or lower quality services, unless regulation severely constrains market forces, as it does in countries such as Japan. In the most extreme cases, privatisation of natural monopolies can mean more deaths – ranging from casualties of rail accidents caused by under-investment in safety to untimely deaths of pensioners weakened by inadequate heating.

When Royal Mail joins this list, we can be assured that deliveries to remote areas will become less frequent and/or more expensive, while postal workers will have greater workload and less time for human contact.

The point is that markets are run on the principle of "one pound, one vote", which means that those who have enough money can fulfil even the most frivolous of their desires, while those who don't may starve to death. And it is because we don't want such outcomes that humanity has learned to control market forces through public regulation – ideally decided on the "one person, one vote" principle of democracy.

As a result, over time, many things have been taken out – at least partially – of the market: human beings (slaves), child labour, public offices, basic education, healthcare and so on. Even for the marketed things, how you can make money out of them has come under increasing restrictions. For example, in the old days drugs did not require an approval before sales, and companies did not have to reveal anything about themselves when selling shares.

Of course, in the past few decades, the trend towards such "de-marketisation" has been reversed in many countries, especially in the UK. However, that was not because the boundaries of the market as they existed in the 1960s and 70s had been drawn in violation of some natural laws, as the proponents of deregulation and privatisation like to suggest. It was mainly due to the shift in political balance of power towards the moneyed classes, which has unfortunately been accelerating in recent years.

The argument that there are no natural boundaries of the market is best illustrated bySingapore. This successful country is often portrayed as the paragon of free market, but it is actually something quite different. All of its land is publicly owned, 85% of housing is supplied by the public housing corporation and more than 20% of national output is produced by public enterprises, in industries ranging from shipbuilding and semi-conductors to airlines and banking.

Saying that there is no one correct way of drawing boundaries around the market is, of course, not to say that we can do without markets. Vibrant markets are essential for generating prosperity and improving human welfare, as the counter-examples of the Soviet bloc countries show. But that does not mean that more market forces are always better, in the same way in which salt is essential for our survival but too much of it is harmful.

Markets are in the end man-made devices for utilitarian purposes, not a force of nature that we should not try to resist. If they end up serving the interests of only a tiny minority, as is increasingly the case, we have the right – and indeed the duty – to regulate them in the interest of greater social good.