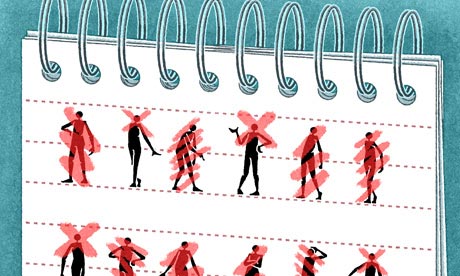

'Workers across Britain have been systematically and illegally forced into unemployment by some of the country's biggest companies.' Illustration by Matt Kenyon

As in the phone-hacking scandal, the evidence of illegality, surveillance and conspiracy is incontrovertible. In both cases, the number of victims already runs into thousands. And household names are deeply tied up in both controversies – though as targets in one and perpetrators in the other.

But when it comes to the blacklisting scandal, the damage can't only be measured in distress and invasion of privacy. Its impact has already been felt in years of enforced joblessness, millions of pounds in lost income, family and psychological breakdown, emigration and suicides.

It's now clear that workers across Britain have been systematically and illegally forced into unemployment for trade union activity – often on publicly funded projects and in collusion with the police and security services – by some of the country's biggest companies, using secret lists drawn up by corporate spying agencies.

Liberty has equated blacklisting with phone hacking, insisting that the "consequences for our democracy are just as grave". Keith Ewing, professor of public law at King's College London, calls it the "worst human rights abuse in relation to workers" in Britain in half a century.

But whereas David Cameron ordered a public inquiry into hacking, he rejected any investigation of blacklisting out of hand. And while a mainly anti-union media has largely ignored the scandal, all the signs are that it's continuing right now, in flagship public projects such as the £15bn Crossrail network across the south-east.

Thanks to leaks, tribunals, evidence to MPs and an information commissioner's raid, we now know that one of those private espionage outfits, the Consulting Association, had 3,213 names on its blacklist before it was shut down in 2009. Most were construction workers, based at sites from Clwyd to Croydon, but they also included environmental activists.

For an annual subscription of £3,500, 44 construction and outsourcing giants such as Balfour Beatty, Carillion, Sir Robert McAlpine and Wimpey paid £2.20 a shot for "intelligence" on the 40,000 names a year they ran past the association's database.

For that they could have access to such gems as "keeps extremely interesting company", "union activity", "brought in H&S issues", "politically motivated", "troublemaker", "recently seen at a leftwing meeting" and "girlfriend … involved in several marriages of convenience". Mostly, workers were branded "involved in dispute" or "company given details and not employed".

Through this covert power, building workers were driven on to the dole during a construction boom. Both Dave Smith, an engineer, and Steve Acheson, an electrician, were sacked from one major construction job after another after raising health and safety concerns (asbestos and lack of drying facilities) over a decade ago. They have never been able to work in the trade for more than a few weeks ever since.

Their cards had been marked by blacklisters. "Those people ruined my life," Acheson says. For some workers, they destroyed it. After hundreds involved in disputes on London's Jubilee line extension were blacklisted in 2000, at least two who were unable to find work committed suicide.

The Consulting Association, which used material the Information Commissioner's office said "could only be supplied by the police or security services", was fined £5,000 for breaching data protection law (paid by the Conservative donor Sir Robert McAlpine). Blacklisting was formally outlawed in 2010, but covert arrangements are by their nature difficult to expose.

Corporate managers who have been revealed to have been up to their necks in blacklisting are now running major publicly funded projects – including Crossrail and the Carillion-run PFI Great Western Hospital in Swindon – that are the focus of new blacklisting and bullying disputes.

Last week, Ian Kerr, the man who headed the Consulting Association, spoke in public for the first time, telling MPs there had been an "awful lot of discussion" between Crossrail contractors and his outfit, as well as those at the Olympic Park, Wembley stadium and other public construction projects. "Like it or not," he declared, blacklisting "will always be there".

Of course blacklisting isn't new. Throughout the cold war, the virulently rightwing Economic League ran a similar corporate espionage outfit, from where Kerr brought his database. And more recently civil servants, police and corporations have been shown to work hand in glove against climate change and other environmental activists.

Nor is blacklisting confined to construction, where unions still have real power. But in a deregulated economy – where union weakness has helped slash the share of wages in national income and an anti-union firm such as Starbucks can announce it's cutting staff benefits on the day it's in the public dock for tax dodging – this ugly corporate victimisation isn't just an outrage against civil liberties.

It's also a block on the revival of union organisation essential to turning the tide of inequality – and the defence of those paying the price of a failed economic model. Labour, which took 11 years to put its own ban on blacklisting into law out of deference to big business, now needs to commit to tougher rights at work. The scandal of corporate blacklisting doesn't just demand a public inquiry and compensation, but a real shift of direction on power in the workplace.

But when it comes to the blacklisting scandal, the damage can't only be measured in distress and invasion of privacy. Its impact has already been felt in years of enforced joblessness, millions of pounds in lost income, family and psychological breakdown, emigration and suicides.

It's now clear that workers across Britain have been systematically and illegally forced into unemployment for trade union activity – often on publicly funded projects and in collusion with the police and security services – by some of the country's biggest companies, using secret lists drawn up by corporate spying agencies.

Liberty has equated blacklisting with phone hacking, insisting that the "consequences for our democracy are just as grave". Keith Ewing, professor of public law at King's College London, calls it the "worst human rights abuse in relation to workers" in Britain in half a century.

But whereas David Cameron ordered a public inquiry into hacking, he rejected any investigation of blacklisting out of hand. And while a mainly anti-union media has largely ignored the scandal, all the signs are that it's continuing right now, in flagship public projects such as the £15bn Crossrail network across the south-east.

Thanks to leaks, tribunals, evidence to MPs and an information commissioner's raid, we now know that one of those private espionage outfits, the Consulting Association, had 3,213 names on its blacklist before it was shut down in 2009. Most were construction workers, based at sites from Clwyd to Croydon, but they also included environmental activists.

For an annual subscription of £3,500, 44 construction and outsourcing giants such as Balfour Beatty, Carillion, Sir Robert McAlpine and Wimpey paid £2.20 a shot for "intelligence" on the 40,000 names a year they ran past the association's database.

For that they could have access to such gems as "keeps extremely interesting company", "union activity", "brought in H&S issues", "politically motivated", "troublemaker", "recently seen at a leftwing meeting" and "girlfriend … involved in several marriages of convenience". Mostly, workers were branded "involved in dispute" or "company given details and not employed".

Through this covert power, building workers were driven on to the dole during a construction boom. Both Dave Smith, an engineer, and Steve Acheson, an electrician, were sacked from one major construction job after another after raising health and safety concerns (asbestos and lack of drying facilities) over a decade ago. They have never been able to work in the trade for more than a few weeks ever since.

Their cards had been marked by blacklisters. "Those people ruined my life," Acheson says. For some workers, they destroyed it. After hundreds involved in disputes on London's Jubilee line extension were blacklisted in 2000, at least two who were unable to find work committed suicide.

The Consulting Association, which used material the Information Commissioner's office said "could only be supplied by the police or security services", was fined £5,000 for breaching data protection law (paid by the Conservative donor Sir Robert McAlpine). Blacklisting was formally outlawed in 2010, but covert arrangements are by their nature difficult to expose.

Corporate managers who have been revealed to have been up to their necks in blacklisting are now running major publicly funded projects – including Crossrail and the Carillion-run PFI Great Western Hospital in Swindon – that are the focus of new blacklisting and bullying disputes.

Last week, Ian Kerr, the man who headed the Consulting Association, spoke in public for the first time, telling MPs there had been an "awful lot of discussion" between Crossrail contractors and his outfit, as well as those at the Olympic Park, Wembley stadium and other public construction projects. "Like it or not," he declared, blacklisting "will always be there".

Of course blacklisting isn't new. Throughout the cold war, the virulently rightwing Economic League ran a similar corporate espionage outfit, from where Kerr brought his database. And more recently civil servants, police and corporations have been shown to work hand in glove against climate change and other environmental activists.

Nor is blacklisting confined to construction, where unions still have real power. But in a deregulated economy – where union weakness has helped slash the share of wages in national income and an anti-union firm such as Starbucks can announce it's cutting staff benefits on the day it's in the public dock for tax dodging – this ugly corporate victimisation isn't just an outrage against civil liberties.

It's also a block on the revival of union organisation essential to turning the tide of inequality – and the defence of those paying the price of a failed economic model. Labour, which took 11 years to put its own ban on blacklisting into law out of deference to big business, now needs to commit to tougher rights at work. The scandal of corporate blacklisting doesn't just demand a public inquiry and compensation, but a real shift of direction on power in the workplace.