From The Economist

LOUD conversation in a train carriage that makes concentration impossible for fellow-passengers. A farmer spraying weedkiller that destroys his neighbour’s crop. Motorists whose idling cars spew fumes into the air, polluting the atmosphere for everyone. Such behaviour might be considered thoughtless, anti-social or even immoral. For economists these spillovers are a problem to be solved.

Markets are supposed to organise activity in a way that leaves everyone better off. But the interests of those directly involved, and of wider society, do not always coincide. Left to their own devices, boors may ignore travellers’ desire for peace and quiet; farmers the impact of weedkiller on the crops of others; motorists the effect of their emissions. In all of these cases, the active parties are doing well, but bystanders are not. Market prices—of rail tickets, weedkiller or petrol—do not take these wider costs, or “externalities”, into account.

The examples so far are the negative sort of externality. Others are positive. Melodious music could improve everyone’s commute, for example; a new road may benefit communities by more than a private investor would take into account. Still others are more properly known as “internalities”. These are the overlooked costs people inflict on their future selves, such as when they smoke, or scoff so many sugary snacks that their health suffers.

The first to lay out the idea of externalities was Alfred Marshall, a British economist. But it was one of his students at Cambridge University who became famous for his work on the problem. Born in 1877 on the Isle of Wight, Arthur Pigou cut a scruffy figure on campus. He was uncomfortable with strangers, but intellectually brilliant. Marshall championed him and with the older man’s support, Pigou succeeded him to become head of the economics faculty when he was just 30 years old.

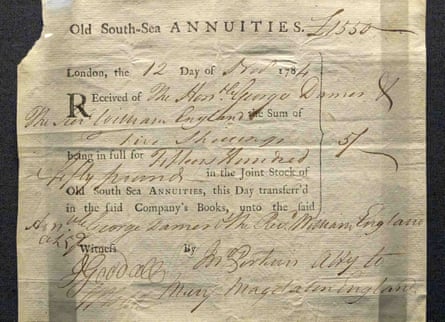

In 1920 Pigou published “The Economics of Welfare”, a dense book that outlined his vision of economics as a toolkit for improving the lives of the poor. Externalities, where “self-interest will not…tend to make the national dividend a maximum”, were central to his theme.

Although Pigou sprinkled his analysis with examples that would have appealed to posh students, such as his concern for those whose land might be overrun by rabbits from a neighbouring field, others reflected graver problems. He claimed that chimney smoke in London meant that there was only 12% as much sunlight as was astronomically possible. Such pollution imposed huge “uncharged” costs on communities, in the form of dirty clothes and vegetables, and the need for expensive artificial light. If markets worked properly, people would invest more in smoke-prevention devices, he thought.

Pigou was open to different ways of tackling externalities. Some things should be regulated—he scoffed at the idea that the invisible hand could guide property speculators towards creating a well-planned town. Other activities ought simply to be banned. No amount of “deceptive activity”—adulterating food, for example—could generate economic benefits, he reckoned.

But he saw the most obvious forms of intervention as “bounties and taxes”. These measures would use prices to restore market perfection and avoid strangling people with red tape. Seeing that producers and sellers of “intoxicants” did not have to pay for the prisons and policemen associated with the rowdiness they caused, for example, he recommended a tax on booze. Pricier kegs should deter some drinkers; the others will pay towards the social costs they inflict.

This type of intervention is now known as a Pigouvian tax. The idea is not just ubiquitous in economics courses; it is also a favourite of policymakers. The world is littered with apparently externality-busting taxes. The French government imposes a noise tax on aircraft at its nine busiest airports. Levies on drivers to counterbalance the externalities of congestion and pollution are common in the Western world. Taxes to fix internalities, like those on tobacco, are pervasive, too. Britain will join other governments in imposing a levy on unhealthy sugary drinks starting next year.

Pigouvian taxes are also a big part of the policy debate over global warming. Finland and Denmark have had a carbon tax since the early 1990s; British Columbia, a Canadian province, since 2008; and Chile and Mexico since 2014. By using prices as signals, a tax should encourage people and companies to lower their carbon emissions more efficiently than a regulator could by diktat. If everyone faces the same tax, those who find it easiest to lower their emissions ought to lower them the most.

Such measures do change behaviour. A tax on plastic bags in Ireland, for example, cut their use by over 90% (with some unfortunate side-effects of its own, as thefts of baskets and trolleys rose). Three years after a charge was introduced on driving in central London, congestion inside the zone had fallen by a quarter. British Columbia’s carbon tax reduced fuel consumption and greenhouse-gas emissions by an estimated 5-15%. And experience with tobacco taxes suggests that they discourage smoking, as long as they are high and smuggled substitutes are hard to find.

Champions of Pigouvian taxes say that they generate a “double dividend”. As well as creating social benefits by pricing in harm, they raise revenues that can be used to lower taxes elsewhere. The Finnish carbon tax was part of a move away from taxes on labour, for example; if taxes must discourage something, better that it be pollution than work. In Denmark the tax partly funds pension contributions.

Pigou flies

Even as policymakers have embraced Pigou’s idea, however, its flaws, both theoretical and practical, have been scrutinised. Economists have picked holes in the theory. One major objection is the incompleteness of the framework, since it holds everything else in the economy fixed. The impact of a Pigouvian tax will depend on the level of competition in the market it is affecting, for example. If a monopoly is already using its power to reduce supply of its products, a new tax may not do any extra good. And if a dominant drinks firm absorbs the cost of an alcohol tax rather than passes it on, then it may not influence the rowdy. (A similar criticism applies to the idea of the double dividend: taxes on labour could cause people to work less than they otherwise might, but if an environmental tax raises the cost of things people spend their income on it might also have the effect of deterring work.)

Another assault on Pigou’s idea came from Ronald Coase, an economist at the University of Chicago (whose theory of the firm was the subject of the first brief in this series). Coase considered externalities as a problem of ill-defined property rights. If it were feasible to assign such rights properly, people could be left to bargain their way to a good solution without the need for a heavy-handed tax. Coase used the example of a confectioner, disturbing a quiet doctor working next door with his noisy machinery. Solving the conflict with a tax would make less sense than the two neighbours bargaining their way to a solution. The law could assign the right to be noisy to the sweet-maker, and if worthwhile, the doctor could pay him to be quiet.

In most cases, the sheer hassle of haggling would render this unrealistic, a problem that Coase was the first to admit. But his deeper point stands. Before charging in with a corrective tax, first think about which institutions and laws currently in place could fix things. Coase pointed out that laws against nuisance could help fix the problem of rabbits ravaging the land; quiet carriages today assign passengers to places according to their noise preferences.

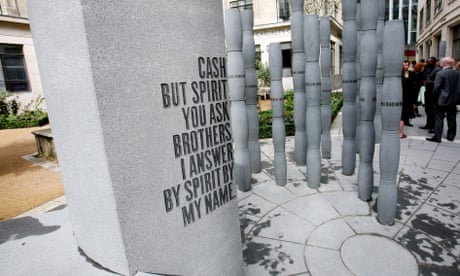

Others reject Pigou’s approach on moral grounds. Michael Sandel, a political philosopher at Harvard University, has worried that relying on prices and markets to fix the world’s problems can end up legitimising bad behaviour. When in 1998 one school in Haifa tried to encourage parents to pick their children up on time by fining them, tardy pickups increased. It turned out that parental guilt was a more effective deterrent than cash; making payments seems to have assuaged the guilt.

Besides these more theoretical qualms about Pigouvian taxes, policymakers encounter all manner of practical ones. Pigou himself admitted that his prescriptions were vague; in “The Economics of Welfare”, though he believed taxes on damaging industries could benefit society, he did not say which ones. Nor did he spell out in much detail how to set the level of the tax.

Prices in the real world are no help; their failure to incorporate social costs is the problem that needs to be solved. Getting people to reveal the precise cost to them of something like clogged roads is asking a lot. In areas like these, policymakers have had to settle on a mixture of pragmatism and public acceptability. London’s initial £5 ($8) fee for driving into its city centre was suspiciously round for a sum meant to reflect the social cost of a trip.

Inevitably, a desire to raise revenue also plays a role. It would be nice to believe that politicians set Pigouvian taxes merely in order to price in an externality, but the evidence, and common sense, suggests otherwise. Research may have guided the initial level of a British landfill tax, at £7 a tonne in 1996. But other considerations may have boosted it to £40 a tonne in 2009, and thence to £80 a tonne in 2014.

Things become even harder when it comes to divining the social cost of carbon emissions. Economists have diligently poked gigantic models of the global economy to calculate the relationship between temperature and GDP. But such exercises inevitably rely on heroic assumptions. And putting a dollar number on environmental Armageddon is an ethical question, as well as a technical one, relying as it does on such judgments as how to value unborn generations. The span of estimates of the economic loss to humanity from carbon emissions is unhelpfully wide as a result, ranging from around $30 to $400 a tonne.

It’s the politics, stupid

The question of where Pigouvian taxes fall is also tricky. A common gripe is that they are regressive, punishing poorer people, who, for example, smoke more and are less able to cope with rises in heating costs. An economist might shrug: the whole point is to raise the price for whoever is generating the externality. A politician cannot afford to be so hard-hearted. When Australia introduced a version of a carbon tax in 2012, more than half of the money ended up being given back to pensioners and poorer households to help with energy costs. The tax still sharpened incentives, the handouts softened the pain.

A tax is also hard to direct very precisely at the worst offenders. Binge-drinking accounts for 77% of the costs of excessive alcohol use, as measured by lost workplace productivity and extra health-care costs, for example, but less than a fifth of Americans report drinking to excess in any one month. Economists might like to charge someone’s 12th pint of beer at a higher rate than their first, but implementing that would be a nightmare.

Globalisation piles on complications. A domestic carbon tax could encourage people to switch towards imports, or hurt the competitiveness of companies’ exports, possibly even encouraging them to relocate. One solution would be to apply a tax on the carbon content of imports and refund the tax to companies on their exports, as the European Union is doing for cement. But this would be fiendishly complicated to implement across the economy. A global harmonised tax on carbon is the stuff of economists’ dreams, and set to remain so.

So, Pigou handed economists a problem and a solution, elegant in theory but tricky in practice. Politics and policymaking are both harder than the blackboard scribblings of theoreticians. He was sure, however, that the effort was worthwhile. Economics, he said, was an instrument “for the bettering of human life.”