Why an initial back-foot trigger movement may not be a great idea

Sanjay Manjrekar

December 18, 2013

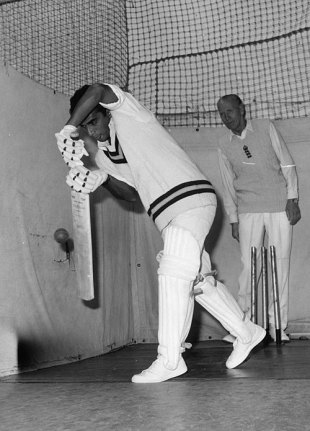

Alastair Cook: too late into position in Perth © Getty Images

A fireman once said, "We are crazy guys, you know. When a house is on fire, people are running out and we are running in." A batsman has to do something similar when a bowler like Mitchell Johnson is steaming in, hurling thunderbolts at 150kph.

Like for the firemen, it is like an inferno approaching a batsman from 22 yards away, and like the fireman, the batsman has a job to do, and it does not include running away. Watching some of the England batsmen in this Ashes series, I have been reminded of this analogy.

When Johnson runs in to bowl, they take a significant step backwards in the crease before the ball is delivered. That is fine when the ball is short, but when it is full - and Johnson bowls a lot of those along with bouncers - they become extremely vulnerable, as we have seen.

----

Also Read - Martin Crowe on Gavaskar's technique

----

Look at Alastair Cook's dismissal in the first innings in Adelaide and in the second in Perth. Both times, the ball was pitched up, but he was just too late to get into position to defend it solidly, which would not have been the case if they were short deliveries. We talk about how great those deliveries from Johnson and Ryan Harris were, and they were good, especially the Harris one in the second innings in Perth, but if Cook had got forward to them quicker, they would have been just two other pitched-up balls that a batsman defended safely.

I am not a big fan of the big back-foot movement - the one batsmen make with their feet before the ball is delivered - unless it's made in order to propel another movement forward. Both the England openers have that initial back-foot movement and only when are set do they use it to spring forward - until then, they seem to hang back a bit and so become vulnerable to balls pitched up, and miss a few scoring opportunities to balls pitched up.

| A short, quick delivery is best handled by a batsman when he is reacting instinctively to it - whether he is playing an attacking shot or defending | |||

With a big initial back-foot movement, you are committing yourself completely to a delivery of a particular length, short. So when the ball is short you seem to have plenty of time to play it, but when it is full you are invariably late on it, and if your luck as a batsman has run out, as Cook found out, that full, seaming ball will come early in the innings, hit the right spot and get through your defence.

As a batsman you ideally want the smallest trigger movement, so that you are prepared for all kinds of lengths and lines. In this Ashes, Michael Clarke, Steve Smith, Joe Root, and also Ben Stokes, have shown that kind of technique, with no pronounced prior commitment to any length. Because of that they have looked much better positioned to balls that are pitched up. Batsmen make the initial move in the crease because that way they feel they are setting themselves up for the challenge. Very often it's just a matter of "mental preparedness". Some do it to be in a good position to face a particular kind of delivery that they feel they are susceptible to.

My view is that if you have to move your feet before the ball is released, it's better to have a front-foot movement instead of a back-foot one: looking to move forward before the ball is bowled rather than back. That way, you are better prepared to handle the ball that gets most batsmen out in this game - the one that is full in length.

What about the short ball then, you ask? Doesn't the front-foot movement make you a sitting duck against it? Well, there you need to trust the instincts that we have all been gifted with as human beings, born of our evolution over millions of years and our survival instincts against physical threats. That short ball from a fast bowler is a physical threat to a batsman. Look at how batsmen react to a short ball from a spinner as opposed to one from a fast bowler.

| |||

As a batsman you will be amazed at how quickly you get on the back foot - though you are telling yourself to go forward - when the ball is short and quick. This back-foot movement happens automatically; it is a case of natural instinct taking over. My argument is, why deliberately try to do something that is going to happen automatically; instead, why not train yourself to do something that is against your instinct? Like getting forward to a fast bowler, because the ball that is pitched up is the one that's most likely to get you out.

The other great benefit in trying to get forward is, that way you also handle the short ball better. I believe that a short, quick delivery is best handled by a batsman when he is reacting instinctively to it - whether he is playing an attacking shot or defending.

During the course of my batting career I had two distinct phases, one when I handled the short ball well and the other when I didn't. It was quite obvious to me that when I was in good form and in a good frame of mind I would look to go towards the fast bowler, try to get on the front foot, and that was when I handled the short ball comfortably. When you are looking to get forward, the head tends to stay forward, and with it the body weight. That is the perfect kind of balance you want to have as a batsman, whether you are playing off front foot or back.

When you are out of form, with a big back-foot movement, the head tends to stay back that fraction of a second longer, and because you are expecting a short ball, the head also stays quite high, which means you are poorly prepared for the full delivery.

Having said all this, there are still many extremely successful contemporary batsmen, like Hashim Amla, Graeme Smith, and Cook himself, who have big back-foot movements. Their success can be attributed to all the other strengths they have brought into play to succeed, but you will see even they look vulnerable early in the innings to balls that are pitched up and seaming.

As a batsman you should have a technique you can fall back on when you are out of form and low on confidence. Your other strengths will have deserted you by then, and your technique will be the only thing you can count on. You need a technique that can get you back into form from a bad patch, and that's where I have a problem with the big back-foot trigger movement.