The health secretary wants adults to look after their elderly parents to combat loneliness, as Asian people do. But Jeremy Hunt is wrong on who loneliness affects, wrong on what causes it, and wrong on what's happening in Asia

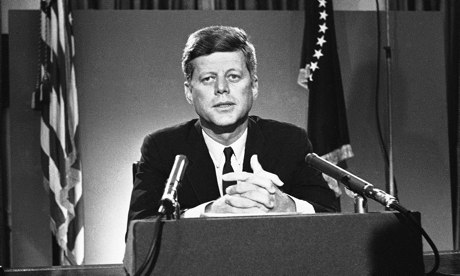

Living alone: Britain has seen a big rise in solo living, from 17% of all households in 1971 to 31% now. Photograph: Zave Smith/Corbis

The officials who broke down Joyce Carol Vincent's door were meant to be serving an eviction notice. Instead they found her corpse slumped on the sofa, with the light from the TV still flickering over her. By 2006, she had lain there for almost three years. Rent demands and other letters flooded the hallway; the food in the fridge had long since expired and piled around her skeleton were the presents she had just wrapped, for Christmas 2003. How Joyce died remains a mystery: there was no evidence of violence and she wasn't into drink or drugs. But the bigger question – the one that catches in your throat – is how it took three years for anyone to discover her death.

An outgoing and pretty 38-year-old, she had sisters, mates, former colleagues and ex-boyfriends. Those social circles appear to have failed her. The bedsit was part of a housing estate above the huge shopping centre in Wood Green, north London, with thousands milling about. But no neighbours reported anything amiss. Joyce's body had rotted so far it could only be identified by comparing dental records with a holiday photo of her smiling. But the stench was put down to whiffy bins, and the flies and insects swarming on the windowsills were ignored.

Even such grotesque details would ordinarily have become mere local gossip – were it not for Carol Morley, who was so disturbed by the story that she made a film about her, with a tenacity of care Joyce didn't enjoy while she was alive. Morley's 2011 drama-documentary, Dreams of a Life, shows city living as a series of weak links, forgettable friendships and single people getting by in their single housing units. By the end of it, you not only understand how a person can disappear from view; you wonder how many others suffer the same fate.

Joyce's story exemplifies the social isolation decried last Friday by Jeremy Hunt as a "national shame". It's an apt subject for a health secretary to address. Studies show that chronic loneliness wrecks one's health: pushing up stress levels, increasing blood pressure, disrupting sleep, even bringing on dementia. And, yes, it kills. The Chicago neuroscientist John Cacioppo, who has researched social seclusion for decades, has tallied up the harm posed by common health hazards. Air pollution increases your chances of dying early by 5%; obesity by 20%. Excessive loneliness pushes up your odds of an early death by 45%.

Hunt doesn't dispute those findings. Indeed, last week he brought forth some shockers of his own. Such stats should make tackling isolation a public-health priority for any government. This one, however, seems to be doing its best to increase loneliness: its bedroom tax and housing-benefit cuts are wrenching families out of their communities and driving them into other neighbourhoods, even other cities.

No surprise that this didn't elicit even a sentence from Hunt. More troubling is to see a set-piece ministerial intervention – with lobby briefings, press releases, newspaper splashes, the lot – tackle an important subject in an utterly trivial fashion.

Loneliness, if we are to believe the health secretary, is a problem that afflicts only the elderly. And it can be solved by adult children looking after their parents, with "the reverence and respect" of their Asian counterparts (who also, handily enough, make do without all that welfare-state padding). In the east, you see, "residential care is a last rather than a first option"; while westerners presumably pack their folks off to homes as joyfully as if they were checking them into spas.

Well, we shouldn't believe Jeremy Hunt, because he is wrong on all counts. Wrong on who loneliness affects, wrong on what causes it, and wrong even on what's happening in Asia.

First, surveys by the Mental Health Foundation suggest that young people are more likely to feel lonely than older people. That fits with the other evidence. Britain has seen a big rise in people living alone, from 17% of all households in 1971 to 31% now. But while the proportion of retirees living alone has hardly changed over the past four decades, it's Britons of working age who are increasingly on their own. This lifestyle isn't always a chosen one: think of how the divorce rate has nearly doubled since the 60s.

Solo living coupled with a culture that exalts individualism breeds isolation. Britain's economic model grants its winners all manner of economic freedoms, but it does so while weakening social bonds. Getting on your bike and looking for work, or moving abroad to get a job, means leaving your family and friends behind. Some of these gaps can be filled by consumer onanism and by psychic palliatives such as Facebook and Twitter. But not wholly, and not for long.

In his book, Loneliness, Cacioppo puts it thus: "A rising tide can lift a variety of boats, but in a culture of social isolates, atomised by social and economic upheaval and separated by vast inequalities, it can also cause millions to drown." He might have been thinking of Joyce Vincent.

The flipside of economic individualism is loneliness. And as that model has been exported around the world, even traditionally family-centred cultures have started to crumble. This summer, Beijing passed a law compelling adults to visit their parents, or face jail. And next time Hunt sounds off about eastern reverence for the elderly, he might remember this: the best adult care home in Beijing has a waiting list that is 100 years long.