MS Dhoni wasn't cocky but there wasn't any false modesty either: Greg Chappell

Jonathan Selvaraj Posted online: Sun Oct 06 2013, 01:51 hrs

In Visakhapatnam with the under-19 team, Greg Chappell talks about Australia's changing cricketing mindset and his eventful coaching stint in India. He opens up to Jonathan Selvaraj as he revisits the dressing room that had ageing seniors, an out-of-form captain and a rookie wicket-keeper who was a natural leader.

In what capacity are you connected with the Australia under-19 team?

I’ve come in as National Talent Manager. I’m chairman of our youth selection panel. I’ve been in charge for three years now and I normally travel with the U-19s as a youth selector and manager. But when Stuart Law took up the Queensland job, then we had to do some reshuffling. And that’s why I came back as the coach.

Of late a number of Australia U-19 players have been blooded into first class cricket and the senior team ...

Five years ago we came to the conclusion that it was taking on average four years for the U-19 players to get on state contracts. That was too long. So the Second XI competition was changed to a U-23 competition (Futures League). I think it has been quite successful. Twelve of the players who played the 2010 Junior World Cup went on to get state contracts as did 13 from last year’s World Cup. That’s considering three of our best bowlers — Pat Cummins, Ashton Agar and the wrist spinner James Muirhead — were injured. Those three boys also went on to state contracts and of course Cummins and Agar have played international cricket.

Why do you have to give them a push?

The international programme has become busier and T20 cricket has made it busier still. International players don’t play domestic cricket. And after professionalisation at our domestic level, those players don’t play club cricket. That’s had an impact on the younger players. We have come to the understanding that our club cricket and our domestic cricket can’t do the job that it once did. So we have to identify the ones we think have potential and invest in them.

So doesn’t domestic cricket and the experience that comes with it count?

Playing for ten years doesn’t necessarily give you 10 years’ experience. It could just be that you had one year’s experience ten times. If you are not getting better, then your experience is useless. Performance in domestic cricket up to a point is important but once somebody with the skills that you require shows the ability to score runs or take wickets at that level, the sooner you get them to the next level, the better.

How different is it to coach a U-19 team from a senior team. Are the players scared of you?

No, they are not scared. They are respectful but they are not in awe of me. I am a resource like the rest of our support staff. My role at this level is different from the role at state level and the role at international level.

What is it that you look for in a young cricketer?

It is about assessing their potential. Have they got the skills that historically do well in Test cricket. Can they bowl fast? Are they someone who gets bounce? Can they swing the ball? Do they put some revs on the ball? The first thing I’m interested in, in a batsman is can they read lengths well because that means they are watching the ball. If they are going forward to balls they should be back to then there is a problem. How do they read the game on the field? I am looking for things that the scorecard can’t tell me.

Could you give an example of someone you noticed who read length well during your stint as India coach. What about MS Dhoni?

MS Dhoni came into the one-day team just before I joined as coach. Most people saw him just as a front-foot hitter. One day I saw him batting against Ajit Agarkar on a very slow wicket at the Chinnaswamy Stadium and he was very comfortable on the front foot. Ajit has a very good bouncer and I thought I would like to see how he responds to that. So Ajit bowled him the perfect bouncer and the next thing you know he had hit the ball to the top of the roof. So I said 'Ok he reads length well'. It wasn’t as if he was constantly looking to get to the front foot and that was his only skill.

Was that the only thing that set him out?

His reading of the game was incredible. He had a calmness and an inner strength which wasn’t something I had seen a lot of in other cricketers. He was very confident. He wasn’t cocky but there wasn’t any false modesty either. If he thought he could do something, he would go ahead and say he could do it. Both in India and Australia you have a lot of players who are afraid to stand up because they feel they might be thought of as being ahead of themselves or setting themselves up for failure. He had no concerns about that. He was supremely confident in his own ability. He had some work to do with his wicketkeeping but you could see he had the basics. I saw him as far more than a one-day cricketer. I could see him as a Test cricketer. And I could certainly see him as a captain.

Why do you say that?

His ability in the Indian dressing room to move between the seniors and the juniors was unique. There was nobody else I saw that could compare. Even some of the seniors struggled with other seniors. Not just physical strength but also an emotional strength … a spiritual strength. He knew who he was. He didn’t have any doubts about his ability to play at that level.

It wouldn’t have been easy for him. He comes from a state not really known for its cricket.

That’s interesting. We had a camp in Bangalore early on. I wanted the guys to talk about themselves. I had come in knowing some of the senior players because I had seen them play and I had met many of them before. But I wanted to know about their life and cricket. And it was an amazing story of where he had come from and how he had learned his cricket playing on the streets with his friends and at each level how he had to prove himself again because each time he came in he was the new boy. He talked very well about how each of those steps had given him something. Some confidence, some experience, some knowledge.

What were you looking for in these sessions?

I was looking not just for cricketing talent but also something extra which would help them succeed. Not everyone was cut out for a life as a professional cricketer. These guys are on the road for ten months of the year. You are separated from your friends, family and support structures. Not everyone can cope with it. I was looking for that inner strength. That ability to be able to be self-contained. Also you have to have a sense of humor.

Why sense of humour?

This game is about dealing with failure. Bradman batted 80 times in Test cricket and he only got 29 hundreds. So he failed 51 times. The rest of us have had a huge struggle. It’s only those who accept that they are going to fail a lot and have a belief that their method will work will be able to keep at it. Dhoni’s method was and is unique. Not many people play like him, but he has immense confidence in it. And that’s all that really matters.

What did you see in Suresh Raina?

There was an X factor there. He had the ability to score runs quickly. He read length well and he had shots all around the wicket. He was a brilliant fielder, a more-than-useful all-rounder. I saw him first at a camp in Bangalore. This was simply a way for me to see some talent. We had a camp for the bowlers and for the batsmen. There were a lot of good players but only a few had that X factor.

Anyone else with X factor?

Another one was Sreesanth. I was standing on the far side of the ground and I moved to second slip where I had fielded my whole career and that’s a good place for me to get my look at him. And I kept seeing the ball coming through to the keeper. He had a very easy action and there was some pace there. And as I said before, genuine pace excites me. So I spoke to others and they said 'oh no he is from Kerala and he doesn’t get wickets'. So I talked to other people and they said he doesn’t get a lot of wickets but he gets a lot of nicks. He just never had players who could catch the ball. So as I have said before, it isn’t about wickets, it’s about how many times you beat the bat. How often do you get the outside edge, how many times do you hit them on the pads. It could be how many times you can draw a false stroke.

How do you remember your time in India?

Far from regretting the experience, I look back at my time in India with great fondness. Most of my experiences here were very good. There were parts that I could have done without. But that happens. When I look back it was overwhelmingly positive. It was a wonderful opportunity and a great honour to be asked to coach someone else’s country. I couldn’t coach Australia. Coaching India wasn’t the next best thing, it was the best thing. India is the hub of cricket in the world these days and to work in that environment and try and understand it a bit better… I consider myself very fortunate.

How did you try to understand the culture? You read a lot. Did you go through books?

I have a copy of the Bhagavad Gita. I read it, I still read it. I have a copy of the Koran. I read that as well. I’m interested in all of that. (Ramesh) Mane the team physio was a Brahmakumari (follower). We went with him to the temple in Bandra. My wife went to the Hare Krishna temple in Bangalore where they serve meals to thousands of kids. When we went to Pakistan, Saeed Anwar took me to a teaching mosque outside Lahore. I wanted to understand that a bit more because we had Muslim players in our team — Wasim Jaffer, Mohammad Kaif, Irfan Pathan and Zaheer Khan. I felt I needed to understand something. I mean I couldn’t speak the language, and I just wanted to understand their world a little bit better, in the hope that that would help me, help them.

Did the players appreciate that you were trying to understand their world?

They might not have been aware of some of it. I went to Irfan’s home in Baroda and of course they couldn’t speak much English and of course I couldn’t speak any Urdu. But you look into someone’s eyes and you can understand. Irfan’s mother spoke to my wife and she said “thank you for looking after my son". And we got a thrill from the fact that they appreciated that we were looking after their kids. And they were like our kids. Because they were young, they were vulnerable and they needed someone to look out for them.

So what were the high points of your stay?

My only interest in the time that I was in India was what was best for the Indian cricket team. The whole thing was a spiritual experience. The education point of view was one thing that we really focused on. India was struggling in one-day cricket, particularly chasing. And we made a process of getting the team to understand how to chase. And when we had seventeen wins in a row that was an enormous achievement. And it wasn’t an achievement for me, it was an achievement for that group. They had to buy into it. Rahul Dravid as captain had to buy into it. There were a lot of risks. There were criticisms we were changing the team, we were changing the batting order.. And the fact that we got the guys buying in was tremendous.

What went wrong when you were coach of India?

AS you know in that role, the spotlight is such that nobody wants to understand what is going on underneath. All they saw was what they wanted to. If it had worked, you would be a hero and if it hadn’t, you would have been a zero. Generally what I have found in life is what you see isn’t necessarily the whole story. But no one was really looking at what Greg Chappell the coach was saying, and try and understand Greg Chappell the person. I tried to explain what we were trying to do, but in fact, it was counterproductive. People just used it against me.

Have you made your peace with not just what happened but some of the people involved?

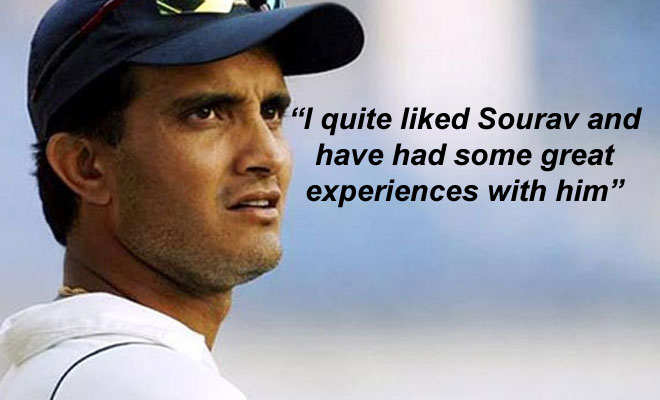

I haven’t spoken to some of them, but you move on. I was in Kolkata earlier in the year and I learned that Sourav’s father had passed away and I rang him and spoke to him at that time and passed on condolences.

Was he surprised?

I’m sure he was a little surprised but he said he appreciated it very much. As I explained to him at the time it wasn’t anything personal (about the decisions I made). I rather liked Sourav and I admired him as a cricketer but at that point he probably wasn’t the best person to be in that position.

Could you have avoided some of the decisions?

When you take a decision, you go with it all the way regardless of what happens. I believed and it was agreed that this was the best team for Indian cricket and the team at that stage. Sections of the media wanted to portray that it was me against Sourav. But it was nothing to do with that. It was purely to do with the cricket. In fact I quite liked Sourav and I have had some great experiences with him. He had been with me in Sydney before the tour of Australia in 2003, and it was a wonderful experience. And I said it before and even subsequent to the issues that we have had that Sourav considers me the best batting coach he ever had. So we had a mutual respect but I hardly expected him to agree with some of the decisions I made. But our relationship was separate from our job. If he had been my brother I would have done the same thing.