‘When asked where it obtains its minerals, Apple looks arrogant, lumbering and unaccountable.' Photograph: Eduardo Barraza/Demotix/Corbis

Are you excited about the launch of Apple's new iPhones? Have you decided to get one? Do you have any idea what you're buying? If so, you are on your own. When asked where it obtains its minerals, Apple, which has done so much to persuade us that it is deft, cool and responsive, looks arrogant, lumbering and unaccountable.

The question was straightforward: does Apple buy tin from Bangka Island? The wriggling is almost comical.

Nearly half of global tin supplies are used to make solder for electronics. About 30% of the world's tin comes from Bangka and Belitung islands in Indonesia, where an orgy of unregulated mining is reducing a rich and complex system of rainforests and gardens to a post-holocaust landscape of sand and acid subsoil. Tin dredgers in the coastal waters are also wiping out the coral, the giant clams, the local fisheries, the endangered Napoleon wrasse, the mangrove forests and the beaches used by breeding turtles.

Children are employed in shocking conditions. On average, one miner dies in an accident every week. Clean water is disappearing, malaria is spreading as mosquitoes breed in abandoned workings, and small farmers are being driven from their land. Those paragons of modernity – electronics manufacturers – rely for their supplies on some distinctly old-fashioned practices.

Friends of the Earth and its Indonesian counterpart, Walhi, which have documented this catastrophe, are not calling for an end to tin-mining on Bangka and Belitung: they recognise that it supports many people who would not find work elsewhere. What they want is transparency on the part of the companies buying the tin extracted there, leading to an agreement to reduce the impacts and protect the people and the wildlife. Without transparency there's no accountability; without accountability there's no prospect of improvement.

So they approached the world's biggest smartphone manufacturers, asking whether they are using tin from Bangka. All but one of the big brands fessed up. Samsung, Philips, Nokia, Sony, BlackBerry, Motorola and LG admit to buying (or probably buying) tin from the island through intermediaries, and have pledged to help address the mess. One company refuses to talk.

Tim Cook, Apple's chief executive officer, claimed last year: "we want to be as innovative with supply responsibility as we are with our products. That's a high bar. The more transparent we are, the more it's in the public space. The more it's in the public space, the more other companies will decide to do something similar". Which would be fine, if Apple did not appear to be pursuing the opposite policy.

Mobilised by Friends of the Earth, 25,000 people have now written to the company to ask whether it is buying tin from the ecological disaster zone in Indonesia. The answer has been a resounding "we're not telling you".

I approached Apple last week, and it felt like the kind of interview you might conduct with someone selling televisions out of the back of a lorry. The director of corporate public relations refused to let me record our conversation. He insisted that it should be off the record and for background only, whereupon he told me ... nothing at all. All he would do was direct me back to the webpage I was asking him about.

This states, with baffling ambiguity, that "Bangka Island, Indonesia, is one of the world's principal tin-producing regions. Recent concerns about the illegal mining of tin from this region prompted Apple to lead a fact-finding visit to learn more." Why conduct a fact-finding visit if you're not using the island's tin? And if you are using it, why not say so? Answer comes there none.

Today I asked him a different set of questions. In a previous article, in March, I praised Apple for mapping its supply chain and discovering that it uses metals processed by 211 smelters around the world. But, in view of its farcical response to my questions about Bangka, I began to wonder how valuable that effort might be. Apple has still not named any of the companies on the list, or provided any useful information about its suppliers.

So I asked the PR director whether I could see the list, and whether it has been audited: in other words, whether there's any reason to believe that this is a step towards genuine transparency. His response? To direct me back to the same sodding webpage. Strange to relate, on reading it for the fourth time I found it just as uninformative as I had the first time.

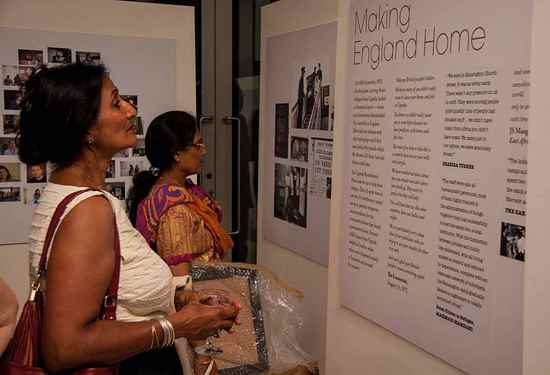

While I was tearing out my hair over Apple's evasions, Fairphone was launching its first handset at the London Design Festival. This company, formed not just to build a genuine ethical smartphone but also to try to change the way in which supply chains and commercial strategies work, looks like everything that Apple should be but isn't. Though its first phone won't be delivered until December, it has already sold 15,000 sets: to people who want 21st-century technology without 19th-century ethics.

The Restart Project, which helps people to repair their own phones (something that Apple's products often seem designed to frustrate) was at the same show, pointing out that the most ethical phone is the one you have in your pocket, maintained to overcome its inbuilt obsolescence.

This isn't the only way in which Apple looks out of date. Last week, 59 organisations launched their campaign for a tough European law obliging companies to investigate their supply chains and publish reports on their social and environmental impacts. Why should a company be able to choose whether or not to leave its customers and shareholders in the dark? Why shouldn't we know as much about its impacts as we do about its financial position?

Until Apple answers the questions those 25,000 people have asked, until it displays the transparency that Tim Cook has promised but failed to deliver, don't buy its products. Made by a company which looks shifty, unaccountable and frankly ridiculous, they are the epitome of uncool.