The digital economy operates as a kind of sophisticated

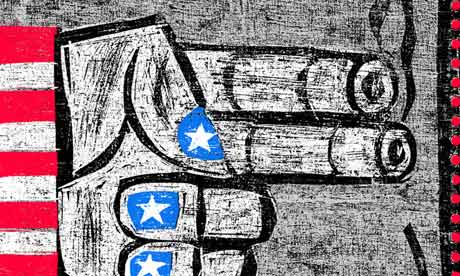

X Factor: someone will make it, but most won't – and the real loser is society

X Factor: someone will make it, but most won't – and the real loser is society

Mary Portas, whose company offered a week-long internship at a Westminster school auction. Photograph: Richard Young/Rex Features

Never mind checking your privilege. Flaunting those enviable privileges is where it's at. Go to any of our big cities and cash will be flowing through ponced-up restaurants nestled between Poundland and the nail bars. They even wave it in our faces.

Already at a private school that charges £7,000 a term? Then you must need a hand up the ladder. So let Mater and Pater bid as internships for Mary Portas or Fabergé are auctioned off. Not so much getting a foot in the door as crowbarring it in with money. Theirs is a world in which austerity remains an abstract idea.

Meanwhile, we have more than a million Neets in the country – young people not in work, education or training. They could do with a helping hand but they have somehow missed the boat. It hardly matters to them that the boat was the Titanic. Their older brothers and sisters have gone to college but are still in a world of part-time pub jobs. They don't have proper salaries and therefore no chance of mortgages. And, of course, in other European countries the situation is even worse.

At this point it is customary to blame the banksters. Or at least the politicians. But there is another group partly responsible for the parlous state in which we find ourselves: the digi-heads of Silicon Valley who told us everything could be kinda free. And easy. In some virtual paradise.

But it's not lovely being asked to work for free, whether you are 18 or 48. On the popular free app known as Facebook, the great music writer Barney Hoskyns put up a manifestothat struck home: he asked "freelance content providers" – be they actors, writers, musicians or photographers – to withdraw from unpaid labour. (I did that a while back – except, of course, for causes I believe in.)

But this is about more than that. It's about technology taking jobs, about what it can and can't provide. Hoskyns quotes Jaron Lanier's new book Who Owns The Future?, in which he argues: "Capitalism only works if there are enough successful people to be customers." Lanier, a computer scientist and a musician, is rightly called a visionary because he sees what is happening, when everything is live-streamed but no one knows the name of the person who made the music any more. Content is free.

Governments play up the idea that a digital future creates jobs rather than eats them up. Culturally, there is now a fantasy world of start-ups and blogs and YouTube TV where a very few people manage to make money but most work simply for "experience".

In an interview with Scott Timberg for Salon, Lanier gives a potent example: Kodak used to have "140,000 really good middle-class employees. Instagram has 13 employees, period." He describes a winner-takes-all world, with a tiny number of successful people and everyone else living on hope. "There is not a middle-class hump. It's an all-or-nothing society."

We can shrug and say it's just another industrial revolution, a move from formal to informal work, the whole "portfolio" number. But where is the social contract, then, if it "doesn't tide you over when you're sick and it doesn't let you raise kids and it doesn't let you grow old"?

The implosion of the middle class produces instability. We cannot all be freelancers for ever. Freelance work, like interning, is fine if you have the funds to manage without a regular income. That is, if you are already wealthy. But the digital economy operates as a kind of sophisticated X Factor. Someone will make it, sure. For more than 15 seconds even, maybe. But most won't. This is why Lanier says the internet may destroy the middle classes, the people who can't outspend the elite. And without that middle group, we cannot maintain a democracy.

He sees musicians and artists and journalists as canaries in the mineshaft of this new economy. Who will pay them? "Is this the precedent we want to follow for our doctors and lawyers and nurses and everybody else? Because, eventually, technology will get to everybody."

Education and healthcare farmed out to the bright-eyed tech nerds? It's already happening. We are already missing the human touch in our hospitals and schools. Gove'snew iPad-levels still cut out the creative subjects from the core – and just when we need the innovations they bring the most. Growth – the holy grail, with nearly half of all European youth unemployed – is impeded when technology eats into job security and therefore has repercussions for pensions and benefits. Those without salaried work cannot hope to support an older generation.

The creative industries, first music and now journalism, saw these changes coming too late. My children have been brought up in a world where they have to compete with those who will work for free. It is only a matter of time until we will all be asked to do the same. And I refuse.

For what is being eroded is not only actual wages but also the very idea that work must be paid for. Huge profits are being made from these so-called opportunities for our youth. But they are, in fact, the exploitation of insecurity. This is not about being anti-technology. It is about being pro-human. Technology is here and it's often great. But we must find a sustainable way of using it so that the stuff we do or make is paid for in living and not virtual wages.