'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 9 May 2013

The sun is at last setting on Britain's imperial myth

The atrocities in Kenya are the tip of a history of violence that reveals the repackaging of empire for the fantasy it is

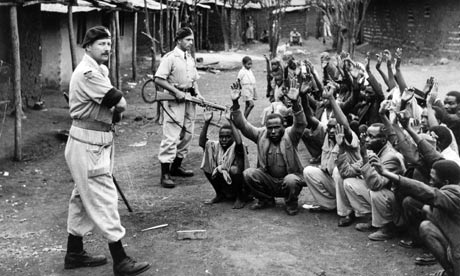

'Consider how Niall Ferguson deals with the Kenyan emergency: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of 'our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security' in his book Empire.' Photograph: Popperfoto/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Scuttling away from India in 1947, after plunging the jewel in the crown into a catastrophic partition, "the British", the novelist Paul Scott famously wrote, "came to the end of themselves as they were". The legacy of British rule, and the manner of their departures – civil wars and impoverished nation states locked expensively into antagonism, whether in the Middle East, Africa or the Malay Peninsula – was clearer by the time Scott completed his Raj Quartet in the early 1970s. No more, he believed, could the British allow themselves any soothing illusions about the basis and consequences of their power.

Scott had clearly not anticipated the collective need to forget crimes and disasters. The Guardian reports that the British government is paying compensation to the nearly 10,000 Kenyans detained and tortured during the Mau Mau insurgency in the 1950s. In what has been described by the historian Caroline Elkins as Britain's own "Gulag", Africans resisting white settlers were roasted alive in addition to being hanged to death. Barack Obama's own grandfather had pins pushed into his fingers and his testicles squeezed between metal rods.

The British colonial government destroyed the evidence of its crimes. For a long time the Foreign and Commonwealth Office denied the existence of files pertaining to the abuse of tens of thousands of detainees. "It is an enduring feature of our democracy," the FCO now claims, "that we are willing to learn from our history."

But what kind of history? Consider how Niall Ferguson, the Conservative-led government's favourite historian, deals with the Kenyan "emergency" in his book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of "our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security."

The British had slaughtered the Kikuyu a few years before. But for Ferguson "it was a magical time, which indelibly impressed on my consciousness the sight of the hunting cheetah, the sound of Kikuyu women singing, the smell of the first rains and the taste of ripe mango".

Clearly awed by this vision of the British empire, the current minister for education asked Ferguson to advise on the history syllabus. Schoolchildren may soon be informed that the British empire, as Dominic Sandbrook wrote in the Daily Mail, "stands out as a beacon of tolerance, decency and the rule of law".

Contrast this with the story of Albert Camus, who was ostracised by his intellectual peers when a sentimental attachment to the Algeria of his childhood turned him into a reluctant defender of French imperialism. Humiliated at Dien Bien Phu, and trapped in a vicious counter-insurgency in Algeria, the French couldn't really set themselves up as a beacon of tolerance and decency. Other French thinkers, from Roland Barthes to Michel Foucault, were already working to uncover the self-deceptions of their imperial culture, and recording the provincialism disguised by their mission civilisatrice. Visiting Japan in the late 1960s, Barthes warned that "someday we must write the history of our own obscurity – manifest the density of our narcissism".

Perhaps narcissism and despair about their creeping obscurity, or just plain madness explains why in the early 21st century many Britons, long after losing their empire, thought they had found a new role: as boosters to their rich English-speaking cousins across the Atlantic.

Astonishingly, British imperialism, seen for decades by western scholars and anticolonial leaders alike as a racist, illegitimate and often predatory despotism, came to be repackaged in our own time as a benediction that, in Ferguson's words, "undeniably pioneered free trade, free capital movements and, with the abolition of slavery, free labour". Andrew Roberts, a leading mid-Atlanticist, also made the British empire seem like an American neocon wet dream in its alleged boosting of "free trade, free mobility of capital … low domestic taxation and spending and 'gentlemanly' capitalism".

Never mind that free trade, introduced to Asia through gunboats, destroyed nascent industry in conquered countries, that "free" capital mostly went to the white settler states of Australia and Canada, that indentured rather than "free" labour replaced slavery, and that laissez faire capitalism, which condemned millions to early death in famines, was anything but gentlemanly.

These fairytales about how Britain made the modern world weren't just aired at some furtive far-right conclave or hedge funders' retreat. The BBC and the broadsheets took the lead in making them seem intellectually respectable to a wide audience. Mainstream politicians as well as broadcasters deferred to their belligerent illogic. Looking for a more authoritative audience, the revanchists then crossed the Atlantic to provide intellectual armature to Americans trying to remake the modern world through military force.

Of course, like Camus – who never gave any speaking parts to Arabs when he deigned to include them in his novels set in Algeria – the new bards of empire almost entirely suppressed Asian and African voices. The omission didn't matter in a world where some crass psychologising about gay men triggers an instant mea culpa (as it did with Ferguson's Keynes apology), but no regret, let alone repentance, is deemed necessary for a counterfeit imperial history and minatory visions of hectically breeding Muslims – both enlisted in large-scale violence against voiceless peoples.

Such retro-style megalomania, however, cannot be sustained in a world where, for better and for worse, cultural as well as economic power is leaking away from the old Anglo-American establishment. An enlarged global public society, with its many dissenting and corrective voices, can quickly call the bluff of lavishly credentialled and smug intellectual elites. Furthermore, neo-imperialist assaults on Iraq and Afghanistan have served to highlight the actual legacy of British imperialism: tribal, ethnic and religious conflicts that stifled new nation states at birth, or doomed them to endless civil war punctuated by ruthless despotisms.

Defeat and humiliation have been compounded by the revelation that those charged with bringing civilisation from the west to the rest have indulged – yet again – in indiscriminate murder and torture. But then as Randolph Bourne pointed out a century ago: "It is only liberal naivete that is shocked at arbitrary coercion and suppression. Willing war means willing all the evils that are organically bound up with it."

This is as true for the Japanese, the self-appointed sentinel of Asia and then its main despoiler during the second world war, as it is for the British. Certainly, imperial power is never peaceably acquired or maintained. The grandson of a Kenyan once tortured by the British knows this too well as: having failed to close down Guantánamo, he resorts to random executions through drone strikes.

The victims of such everyday violence have always seen through its humanitarian disguises. They have long known western nations, as James Baldwin wrote, to be "caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism". They know, too, how the colonialist habits of ideological deceit trickle down and turn into the mendacities of postcolonial regimes, such as in Zimbabwe and Syria, or of terrorists who kill and maim in the cause of anti-imperialism.

Fantasies of moral superiority and exceptionalism are not only a sign of intellectual vapidity and moral torpor, they are politically, economically and diplomatically damaging. Japan's insistence on glossing over its brutal invasions and occupations in the first half of the 20th century has isolated it within Asia and kept toxic nationalisms on the boil all around it. In contrast, Germany's clear-eyed reckoning and decisive break with its history of violence has helped it become Europe's pre-eminent country.

Britain's extended imperial hangover can only elicit cold indifference from the US, which is undergoing epochal demographic shifts, isolation within Europe, and derision from its former Asian and African subjects. The revelations of atrocities in Kenya are just the tip of an emerging global history of violence, dispossession and resistance. They provide a new opportunity for the British ruling class and intelligentsia to break with threadbare imperial myths – to come to the end of themselves as they were, and remake Britain for the modern world.

Cricket as complex narative (or how KP loves himself)

A novelist argues that cricket is more character-revealing than character-building

Patrick Neate

May 9, 2013

| |||

I am currently working on a feature film script. A novelist by trade and instinct, I am finding it a testing process; a tricky exercise of discipline and concision. The opening line, for now at least, is: "You can learn everything you need to know about life from the game of cricket: the old man told me that."

The script is an adaptation of one of my own novels,City of Tiny Lights, a gumshoe I once believed would presage a whole new genre of suburban thriller. I even had a name for it: Chiswick Noir. Good, eh? Almost a decade later, my novel remains, so far as I know, its only exemplar.

The protagonist of City of Tiny Lights is a Ugandan Indian private eye called Tommy Akhtar. He's a hard-drinking, hard-smoking hard man with a fine line in repartee. Tommy and I have little in common but cricket-mad fathers. That opening line is borrowed directly from mine.

Dad was a much better sportsman than I ever was. (Funny, I originally completed that sentence as "than I'll ever be" but, in my forties, perhaps it's finally time to concede defeat.) He played first-class cricket for Oxford alongside the rare talent of Abbas Ali Baig and under the captaincy of the great "Tiger" Pataudi, oncetaking 78 off a touring Australian attack that included the likes of Garth McKenzie and Richie Benaud. He went on to captain Berkshire and play good club cricket for Richmond for many years.

In, I think, 1987, we played side by side in a scratch team that he organised. Chasing around 250, I opened and was out to the first ball of the innings. Our batting soon collapsed and I remember Dad walking out at No. 7 or 8, saying: "I'll just have to do it myself." And he did, returning a couple of hours later with an unbeaten hundred to his name.

Afterwards, in the bar, he enjoyed his moment in the evening sun and we stayed much later than he'd planned. He then had to drive me to Taunton, you see, where my school team was playing the next day. We arrived not much before midnight and then he turned straight round and drove all the way back to London.

On the way to Somerset, he'd told me (in no little detail) how to score a century and, the next afternoon, I duly did, the first of my cricketing life (which makes it sound like many followed - let's leave it like that). I was sorry he was not there to see my innings, but I rang him from a payphone in the evening and he listened while I talked him through every run. I'm not sure what part of this story I find most revealing.

The father-son relationship expressed through sport is a complex thing. We all know the archetype of the competitive dad who loves humiliating his boy at everything from three-and-in to Connect 4. It's not quite equivalent to pinning the kid's feet together and abandoning him on a mountainside, but surely every father of sons has a touch of Laius about him. My old man was certainly no more competitive than most and would never have enjoyed my humiliation, but he never let me win either.

A couple of years later, I was captain of my school first XI. We were an average team led by an average captain, struggling for form. I had never been an expansive batsman, the strongest part of my game a kind of bloody-minded obduracy; but by the time I was 18 I'd stopped moving my feet altogether and just poked at the ball like a tramp at a rubbish bin. I'd turned into some kind of cricketing mollusc: I want to say a schoolboy Chris Tavaré, but I think Jimmy Anderson (the batsman) would be a better comparison. If any captain had set a field with nine arranged in an arc from first slip to point, I'd have never scored a run.

The climax to our season was always the match against the MCC and that year Dad was their captain. They took first knock and racked up a bucket-load of runs.

When we batted, I was determined to do well and I was at my most crustacean. I left a lot and limped (or limpeted) to 30 in about an hour and a half. Then, Dad took the ball himself. I had faced him countless times in the nets and we both knew he was no bowler, a slow-dobbing mixture of legbreaks that didn't break and in-duckers that didn't duck. He arranged his field carefully and at great length - a short leg, slip, gully and the rest in a ring. "Well," he announced to one and all, "we've got to see if they'll go for it."

I left the first delivery and played down the wrong line to the second. To the third, I launched myself up the wicket and swung my bat with, the mythology tells me, "all my might" - Oedipus the King! The King!

Unfortunately, I made no kind of contact and a thick outside edge lobbed a dolly to backward point. Dad declined celebration, like a footballer returning to a much-loved former club. As I walked past, he said: "Bad luck." Then: "This is a very character-building game."

You can learn everything you need to know about life from cricket and when Dad and I now watch we agree on much - for example, that Kevin Pietersen is a genius for our times (i.e. he has made a virtue of stupidity), and that, while Ian Bell must never be asked to bat for our lives, there'd be no better man to arrange flowers prettily at the funeral should Steve Waugh be dismissed. However, Dad's assertion that cricket is "character-building" is, if not wrong, certainly meaningless. Isn't everything character-building? Sitting in a pub, drinking your life away; sitting in a garret, writing your life away; sitting in an armchair, spectating your life away - they're all as character-building as each other. Of course what Dad meant is that cricket builds good character. But I'm not sure there's much evidence for that either. Dad will often say of an acquaintance: "Well, he's a cricketer. Must be all right." But I assume he's joking because, while I've made many friends through cricket, I've met my fair share of tossers too.

Cricket is "the gentleman's game" and the motto "it's just not cricket" spread throughout the Victorian Empire. But, for me, these just bring to mind Oscar Wilde's description of a gentleman as "one who never hurts anyone's feelings unintentionally". After all, the "gentlemen" who decided what was or wasn't cricket were a limited bunch who were, at the time, part of a culture engaged in some of the most rapacious pillaging of other people's resources the world has seen. Cricket was their game and, like the great swathes of pink across the globe, it was played by their esoteric rules. WG Grace may have been the first cricketing genius, but he was also renowned for his gamesmanship and/or cheating (depending on who you believe). And the subsequent century and a half of cricketing history is a litany of nefarious tactics, ball-tampering, match-fixing, surreptitiously effected run-outs, catches claimed and disputed, and so on.

But, perhaps the most telling example of the bizarre hypocrisies of cricket is "walking". Walking (or not) is an issue as old as the game itself. Walking is regarded as the height of gentlemanly conduct, a kind of sporting hara-kiri. And yet, let's face it, the term would never have come into existence were it not for the fact that some (including, of course, the great WG) didn't. Walking is the game's Hippocratic oath and its hypocritical taboo. I remember being given out caught behind at school. When I reached the pavilion, our cricket master chastised me for a full five minutes - cricket is a gentleman's game, he pronounced. If we don't play it like gentlemen, we may as well all give up now. Why didn't you walk? "Because I didn't hit it," I said.

So, I no longer believe that cricket builds character (in any meaningful sense). Instead, I have come to see that cricket reveals it; and isn't that a whole lot more interesting?

| There is something about cricket at its best that sets it apart - the space and time that allow for character development, the empathy and identification between player and spectator, the struggles of an individual against the backdrop of an interwoven narrative of a wider war for ascendancy | |||

All sport is narrative: its central appeal to spectators being the highs and lows, the struggles overcome, that signify a story. But most sports are plot-driven pulp, built on archetypes of heroism and villainy with little of the nuance of truly great storytelling. I don't think it's any coincidence, for example, that football lasts 90 minutes (or 120, with extra time). After all, between 90 and 120 minutes demarcates the ideal Hollywood structure: a formula in which the surprises are necessarily unsurprising since the key purpose of the medium is to reaffirm and reassure. Of course, Bradford City occasionally beat Arsenal and Verbal may or may not be Keyser Söze. But these are the exceptions that confirm the core principles of a limited-narrative medium.

Cricket is, I think, different. If most sport is driven by plot, cricket is driven by character, and the nuances to be found therein are, if not limitless, as diverse as humanity itself. This idea fascinates me.

I sometimes teach novel-writing - such is the fate of novelists of a certain stature (writers of Chiswick Noir, for example). On such courses, my opening gambit generally goes like this: "What is a story? We meet our protagonist at point A. We follow him or her through to point Z. Typically, that protagonist will be faced with a personal flaw or external problem which he or she will have to overcome in the other letters of the alphabet. Enough said."

It is a facetious little speech, but it does the job, more or less, and it allows me then to go on and explain why I consider the novel the premier narrative form.

Allow me to give, say, Middlemarch, George Eliot's masterpiece, the A-to-Z treatment by way of illustration. Dorothea, an idealistic do-gooder, makes an ill-starred marriage to a crusty, deluded intellectual in the mistaken belief that personal and social fulfillment can be found in academic pursuit. After her husband's death, she eventually marries his young cousin, giving up material security and highfalutin ideals for love and, we are left to hope, some degree of redemption.

I haven't read Middlemarch for a while but, from memory, this is an adequate summary. But, it is also ridiculously reductive. Aside from ignoring the other great strands of plot and theme, it denudes our protagonist of all the subtleties of her character that conjure our empathy even as she infuriates and delights us in equal measure.

Put simply, while the 90-minute screenplay is necessarily built on character tropes of assumed common values and expectations, the novel form affords the storyteller space to build complex people who can be by turns comic and tragic, heroic and villainous, idealistic and cynical. My point? At its best, cricket, in its revelation of character, is the sporting equivalent of the novel.

I remember watching a Test match with Dad as a kid. I can't be sure, but I want to say it was during England's home series against Pakistan in 1982. That summer, England dominated the first Test before threatening implosion against the seemingly innocuous swing bowling of Pakistan's opening batsman, Mudassar Nazar. England lost the second Test by ten wickets before scraping home in the third for a series win.

I remember David Gower was particularly bamboozled by Mudassar's gentle hoopers and, after one dismissal, the commentator described his shot as "careless". This was, of course, one of three adjectives most used to characterise Gower throughout his career, the others being "elegant" and "laidback". In fact, so powerful was this critical stereotyping that Gower has become a triangulation point for all left-handed batsmen and, indeed, "careless" dismissals since.

But, on this occasion, Dad took issue. "Careless?" he said. "He's not careless. You don't get to play Test cricket if you don't care."

It's a comment that's stuck with me.

Let us briefly imagine David Gower: The Movie - create its "beat sheet", as the movie business likes to call it. The screenplay would undoubtedly identify "carelessness" as our hero's fatal flaw within the first ten pages, probably illustrated by some anecdote of schoolboy insouciance. Act One would culminate with him striking his first ball in Test cricket to the boundary, before a decline in Gower's fortunes to the Midpoint (say, the time he was dropped for the Oval Test in Ian Botham's great summer of 1981). Our hero would then fight his way back to the end of Act Two where he would ascend to the captaincy for… well, let's make it the "blackwash" series of 1984. He would show renewed mettle in defeat, which would then lead to a grand series win in India, before the glorious summer following culminates in Ashes triumph and a glut of runs for the man himself - the golden boy all grown up. This is the feature film version. I'm not suggesting it's a particularly good feature film, but it pushes the necessary buttons.

David Gower the Novel, on the other hand, would be a very different undertaking. I won't try to plot it here, but I know that we couldn't simply signify our protagonist with "carelessness". In fact, there is no need to plot the novel here since it already exists in the person of Gower himself. And it is a subtle tale that can only be précised to 117 matches, 8231 runs at an average of 44.25 - greatness by anyone's standards. And that is why Dad took offence to that single careless adjective.

All spectators are, of course, guilty of careless description. I have already been so myself, characterising Ian Bell as a flower-arranger. So, by way of contrition, I will use a moment from Bell's career as one of my examples for the comparison of two sports instead of two narrative media.

In 2008, John Terry, Chelsea captain, stepped up to take a penalty in the shoot-out which could win his club the Champions League for the first time. As he struck the ball, he slipped and sent his shot wide. It was a moment of high sporting drama, certainly; if you were a Chelsea fan, some tragedy; if you were one of Terry's many detractors, an instant of glorious schadenfreude. But I challenge anyone to claim it revealed much meaningful about his character. No doubt in Chelsea-hating pubs across the country, JT was derided as a "bottler", but does that even approximate to a truth we believe? The fact is he missed a penalty kick he'd have scored nine times out of ten. He slipped. Shit happens.

Now, let us look at Ian Bell's dismissal in the first innings of the first Test against India in Ahmedabad in 2012. India had scored 521 and England were struggling at 69 for 4 when Bell walked to the wicket. Then, he tried to hit the very first delivery he received back over the bowler's head to the boundary and spooned a simple catch to mid-off. I'm sure commentators used the word "careless", though I don't actually remember the invocation of Gower. It was an extraordinary shot, no doubt, but it also seemed more than that - in some way a summation of Bell as cricketer and man. In no particular order, Bell was batting at No. 6, a kind of ongoing reminder of a perceived weakness - we all know (and he knows) that he has the talent and technique to bat at three, but isn't trusted to do so. We all know his reputation for scoring easy runs - even the game in which he hit his 199 against South Africa in 2008 eventually petered out into a high-scoring draw, while his double-century against India in 2011 was milked from a beaten team at the end of a long summer. The former young maestro was one of three senior pros in the England top six, the go-to men to bat their team out of a crisis. His place in the team was under pressure from the next generation of tyros and he was due to return home after the game for the birth of his first child. Lastly, we all know that cricket is a game in which you have to trust your judgement and, to Bell's credit, he trusted his. Unfortunately, that judgement was terribly flawed, but would we have preferred him to poke forward nervously and nick to the keeper? Perhaps we would. The incident reminded me of something else I tell would-be novelists: when you're writing well, you can reveal more about a character in one moment than in 20 pages of exposition.

| |||

Of course I recognise that the oppositions I describe between cricket and other sports, and the novel and other narrative media, are false. There are plenty of unremarkable cricket matches and careers, plenty of epic examples from any other sport you can think of; innumerable bad, unsophisticated novels and many great films of considerable complexity. Nonetheless, I would maintain that the observations underlying these false oppositions ring true. There is something about cricket at its best that sets it apart - the space and time that allow for character development, the empathy and identification between player and spectator, the struggles of an individual against the backdrop of an interwoven narrative of a wider war for ascendancy (or, if you will, a "team game"). There is something about the novel form which, at its best, is exactly the same. Or, to put it another way, in the words of Tommy Akhtar, private eye, in the last scene of my film: "The Yanks will never get cricket. They'll never understand a five-day Test match that ends in a draw. They like victory and defeat. But victory and defeat are generally nursery rhymes, while a draw can be epic." Cricket, like a novel, like life, often ends in moral stalemate. And it's all the better for it.

If describing Ian Bell as a florist smacks of carelessness, then describing KP as some kind of idiot savant is unfortunate (see the KP Genius Twitter account) so, by way of conclusion, let me rectify that here. After all, the idea for this little essay came about while re-reading Anna Karenina against the backdrop of Pietersen's recent conflict with his team-mates, his captain, his coach, and the ECB.

Pietersen was, I began to consider, rather like poor, doomed Anna. He was regarded as self-serving, his judgement fatally flawed, seemingly hell-bent on alienating himself from his peers. He was characterised as a mercenary, and certainly he had no desire to live in anything but the considerable style to which he was accustomed. But, like Anna, his true tragedy was an ill-starred love: a love that could not be condoned by polite society, but would not be contained by its strictures either. But who did KP love?

As I read on, I slowly came to conclude that KP also resembled Count Vronsky; as Leo Tolstoy describes him, "a perfect specimen of Pietermaritzburg's [sorry, "Petersburg's'] gilded youth". Vronsky is a brave soldier raised for derring-do and impressive in the regulated environment of his regiment. But he is a man of limited imagination whose bravery derives not from moral courage but the whims of his own desires. Indeed, when Vronsky resigns his commission, it is not from principle but to pursue the self-gratification of his love for Anna, a love that can never fulfill either of them.

And so it dawned on me: KP is neither Anna nor Vronsky, he is both of them - the cricketing manifestation of Tolstoy's epic of doomed love.

Is this a step too far? Certainly. But fun, nonetheless…

Wednesday, 8 May 2013

Watch out, George Osborne: Adam Smith, Karl Marx and even the IMF are after you

When even the IMF's free market ideologues recoil from the UK chancellor's austerity politics, democracy itself is at stake

The Spanish Inquisition gets a Monty Python makeover. 'Being told by the IMF to go easy on austerity is like being told by the Spanish Inquisition to be more tolerant of heretics.'

George Osborne and his Treasury officials are gearing up for a fight. They've promised to make life difficult for the other side for the next two weeks. The unlikely opponents are the team of economists visiting from the IMF for a regular policy review.

Why has this routine meeting, which would hardly be noticed outside professional circles, become a confrontation? Because the IMF has recently dropped its support for the chancellor's austerity policy and repeatedly urged him to rethink it. It even said he was"playing with fire" in refusing to change course.

This is an astonishing development. For in the past three decades the IMF has been the standard-bearer for austerity. Back in 1997 it even forced South Korea – with an existing budget surplus and one of the smallest public debts in the world (as a proportion of GDP) – to cut government spending. Only when the policy turned what was already the biggest recession in the country's history into a catastrophe, with more than 100 firms going bankrupt every day for five months, did it do an embarrassing U-turn and allow a budget deficit to develop.

Given this history, being told by the IMF to go easy on austerity is like being told by theSpanish Inquisition to be more tolerant of heretics. The chancellor and his team should be worried.

If even the IMF doesn't approve, why is the UK government persisting with a policy that is clearly not working? Or, for that matter, why is the same policy pushed through across Europe? A certain dead economist would have said it is because the government is "in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor". Dead right.

Current policies in the UK and other European countries are really about making poor people pay for the mistakes of the rich. Millions of poor people have lost their jobs and the support they received through welfare, but how many of those top bankers who caused the crisis have suffered – except for a cancelled knighthood here and a partially returned pension pot there? If anyone has suffered in the financial industry, it is its poorer members – junior analysts who lost their jobs and tellers who are working longer hours for shrinking real wages.

In case you were wondering, it wasn't Karl Marx who wrote the words that I quoted above. He would have never put it so crudely. His version, delivered with typical panache, was that the "executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie". No, those damning words came from Adam Smith, the supposed patron saint of free-market economics.

To Smith and Marx, the class bias of the state was plain to see. They lived at a time when only the rich had votes (if there were elections at all) and so there were few checks on the extent to which they could dictate government policy.

With the subsequent broadening of suffrage, ultimately to every adult, the class nature of the state has been significantly diluted. The welfare state, regulations on monopoly, consumer protection, and protection of worker rights are all things that have been established only because of this political change. Democracy, despite its limitations, is in the end the only way to ensure that policies do not simply benefit the privileged few.

This is, of course, exactly why free-market economists and others who are on the side of the rich have been so negative about democracy. In the old days, free-market economists strongly opposed universal suffrage on the grounds that it would destroy capitalism: poor people would elect politicians who would appropriate the means of the rich and give handouts to the poor, they argued, completely destroying incentives for wealth creation.

Once universal suffrage was introduced, they could not openly oppose democracy. So they started criticising "politics" in general. Politicians, it was argued, would adopt policies that maximised their chances of re-election but damaged the economy – printing money, handing out favours to powerful monopolies, and increasing social welfare spending for the poor. Politicians needed to be prevented from making important policy decisions, the argument went.

On this advice, since the 1980s, many countries have ring-fenced the most important policy areas to keep politicians out. Independent central banks (such as the European Central Bank), independent regulatory agencies (such as Ofcom and Ofgem) and strict rules on government spending and deficits (such as the "balanced budget" rule) have been introduced.

In particularly difficult economic times, it was even argued, we need to insulate economic policies from politics altogether. Latin American military dictatorships were justified in such terms. The recent imposition of "technocratic" governments, made up of economists and bankers who have not been "tainted" by politics, on Greece and Italy comes from the same intellectual stable.

What free-market economists are not telling us is that the politics they want to get rid of are none other than those of democracy itself. When they say we need to insulate economic policies from politics, they are in effect advocating the castration of democracy.

The conflict surrounding austerity policies in Europe is, then, not just about figures on budget, unemployment and growth rate. It is also about the meaning of democracy.

As José Manuel Barroso, the president of the European commission, has recently recognised, the policy of austerity has "reached its limits" in terms of "political and social support". If European leaders, including the British chancellor, keep pushing these policies against those limits, people will inevitably start asking: what is the point of democracy, when policies serve only the interest of the tiny minority at the top? This is nothing less than crunch time for democracy in Europe.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)