George Monbiot in The Guardian

There is an inverse relationship between utility and reward. The most lucrative, prestigious jobs tend to cause the greatest harm. The most useful workers tend to be paid least and treated worst.

I was reminded of this while listening last week to a care worker describing her job. Carole’s company gives her a rota of, er, three half-hour visits an hour. It takes no account of the time required to travel between jobs, and doesn’t pay her for it either, which means she makes less than the minimum wage. During the few minutes she spends with a client, she may have to get them out of bed, help them on the toilet, wash them, dress them, make breakfast and give them their medicines. If she ever gets a break, she told the BBC radio programme You and Yours, she spends it with her clients. For some, she is the only person they see all day.

Is there more difficult or worthwhile employment? Yet she is paid in criticism and insults as well as pennies. She is shouted at by family members for being late and not spending enough time with each client, then upbraided by the company because of the complaints it receives. Her profession is assailed in the media as the problems created by the corporate model are blamed on the workers. “I love going to people; I love helping them, but the constant criticism is depressing,” she says. “It’s like always being in the wrong.”

Her experience is unexceptional. A report by the Resolution Foundation reveals that two-thirds of frontline care workers receive less than the living wage. Ten percent, like Carole, are illegally paid less than the minimum wage. This abuse is not confined to the UK: in the US, 27% of care workers who make home visits are paid less than the legal minimum.

Let’s imagine the lives of those who own or run the company. We have to imagine it because, for good reasons, neither the care worker’s real name nor the company she works for were revealed. The more costs and corners they cut, the more profitable their business will be. In other words, the less they care, the better they will do. The perfect chief executive, from the point of view of shareholders, is a fully fledged sociopath.

Such people will soon become very rich. They will be praised by the government as wealth creators. If they donate enough money to party funds, they have a high chance of becoming peers of the realm. Gushing profiles in the press will commend their entrepreneurial chutzpah and flair.

They’ll acquire a wide investment portfolio, perhaps including a few properties, so that – even if they cease to do anything resembling work – they can continue living off the labour of people such as Carole as she struggles to pay extortionate rents. Their descendants, perhaps for many generations, need never take a job of the kind she does.

Care workers function as a human loom, shuttling from one home to another, stitching the social fabric back together while many of their employers and shareholders, and government ministers, slash blindly at the cloth, downsizing, outsourcing and deregulating in the cause of profit.

It doesn’t matter how many times the myth of meritocracy is debunked. It keeps re-emerging, as you can see in the current election campaign. How else, after all, can the government justify stupendous inequality?

One of the most painful lessons a young adult learns is that the wrong traits are rewarded. We celebrate originality and courage, but those who rise to the top are often conformists and sycophants. We are taught that cheats never prosper, yet the country is run by spivs. A study testing British senior managers and chief executives found that on certain indicators of psychopathy their scores exceeded those of patients diagnosed with psychopathic personality disorders in the Broadmoor special hospital.

If you possess the one indispensable skill – battering and blustering your way to the top – incompetence in other areas is no impediment. The former Hewlett-Packard chief executive Carly Fiorina features prominently on lists of the worst US bosses: quite an achievement when you consider the competition. She fired 30,000 workers in the name of efficiency yet oversaw a halving of the company’s stock price. Morale and communication became so bad that she was booed at company meetings. She was forced out, with a $42m severance package. Where is she now? About to launch her campaign as presidential candidate for the Republican party, where, apparently, she is considered a serious contender. It’s the Mitt Romney story all over again.

At university I watched in horror as the grand plans of my ambitious friends dissolved. It took them about a minute, on walking into the corporate recruitment fair, to see that the careers they had pictured – working for Oxfam, becoming a photographer, defending the living world – paid about one fiftieth of what they might earn in the City. They all swore they would leave to follow their dreams after two or three years of making money; none did. They soon adjusted their morality to their circumstances. One, a firebrand who wanted to nationalise the banks and overthrow capitalism, plunged first into banking, then into politics. Claire Perry now sits on the frontbench of the Conservative party. Flinch once, at the beginning of your career, and they will have you for life. The world is wrecked by clever young people making apparently sensible choices.

The inverse relationship doesn’t always hold. There are plenty of useless, badly paid jobs, and a few useful, well-paid jobs. But surgeons and film directors are greatly outnumbered by corporate lawyers, lobbyists, advertisers, management consultants, financiers and parasitic bosses consuming the utility their workers provide. As the pay gap widens – chief executives in the UK took 60 times as much as the average worker in the 1990s and 180 times as much today – the uselessness ratio is going through the roof I propose a name for this phenomenon: klepto-remuneration.

There is no end to this theft except robust government intervention: a redistribution of wages through maximum ratios and enhanced taxation. But this won’t happen until we challenge the infrastructure of justification, built so carefully by politicians and the press. Our lives are damaged not by the undeserving poor but by the undeserving rich.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label wages. Show all posts

Showing posts with label wages. Show all posts

Thursday, 2 April 2015

Tuesday, 24 March 2015

Inflation falls to 0%: what does it mean for the UK economy?

With average earnings growing by just under 2%, living standards should rise and interest rates should remain low but it’s not all good news

Larry Elliott in The Guardian

Britain is within a month of a period of deflation. When the figures for March come out next month lower energy bills mean that the cost of living will be lower than it was a year earlier.

These are uncharted waters for the UK, at least in the modern era. There have been times when inflation has turned negative but they have been few and far between since the second world war, and there have been none since the move to the consumer prices index as the preferred yardstick.

The general assumption is that this is good news, for two reasons. The first is that the fall in inflation boosts living standards, because wages are rising faster than prices. Wages have risen extremely slowly since the recession of 2008-09 and even against a backdrop of falling unemployment are currently only going up by 1.6% a year.

But the sharp drop in oil prices in the second half of 2014 has pushed inflation lower and meant those modest wage increases now stretch further. This is clearly welcome news for the government, eager to fend off Labour’s accusation that the coalition has presided over a cost-of-living crisis. The opposition will say that the recent increase in living standards does not make up for the earlier falls.

The second boost to consumers comes from the outlook for interest rates. It will come as no surprise to the Bank of England that inflation now stands at zero, and the Bank’s governor, Mark Carney, has said it would be “foolish” to cut the cost of borrowing in response to what is thought to be a temporary fall in commodity prices.

That said, the Bank is not going to be in a hurry to raise rates either. All nine members of the Bank’s monetary policy committee are in favour of official interest rates remaining at 0.5%, which is where they have been since early 2009. They look like remaining there for the rest of this year, and one MPC member – Andy Haldane, the Bank’s chief economist – says he can contemplate voting to cut borrowing costs.

That’s because there’s a potential dark side to the fall in inflation, namely the risk that it becomes a permanent feature of the economic landscape. The reason the majority of economists view February’s zero inflation as benign is because they think lower unemployment will put upward pressure on wage settlements. Higher pay deals will start to push up inflation at a time when last year’s drop in oil prices starts to unwind. There is, on this view, little prospect of deflation becoming embedded, as it did in Japan.

This, though, assumes that wage settlements are not dragged lower by the drop in inflation. The fact that average earnings are growing at an annual rate of below 2% even after two years of a relatively robust period of growth is indicative of a labour market where employers are able to secure workers cheaply. They may be tempted to be even less generous once inflation goes negative.

Larry Elliott in The Guardian

Britain is within a month of a period of deflation. When the figures for March come out next month lower energy bills mean that the cost of living will be lower than it was a year earlier.

These are uncharted waters for the UK, at least in the modern era. There have been times when inflation has turned negative but they have been few and far between since the second world war, and there have been none since the move to the consumer prices index as the preferred yardstick.

The general assumption is that this is good news, for two reasons. The first is that the fall in inflation boosts living standards, because wages are rising faster than prices. Wages have risen extremely slowly since the recession of 2008-09 and even against a backdrop of falling unemployment are currently only going up by 1.6% a year.

But the sharp drop in oil prices in the second half of 2014 has pushed inflation lower and meant those modest wage increases now stretch further. This is clearly welcome news for the government, eager to fend off Labour’s accusation that the coalition has presided over a cost-of-living crisis. The opposition will say that the recent increase in living standards does not make up for the earlier falls.

The second boost to consumers comes from the outlook for interest rates. It will come as no surprise to the Bank of England that inflation now stands at zero, and the Bank’s governor, Mark Carney, has said it would be “foolish” to cut the cost of borrowing in response to what is thought to be a temporary fall in commodity prices.

That said, the Bank is not going to be in a hurry to raise rates either. All nine members of the Bank’s monetary policy committee are in favour of official interest rates remaining at 0.5%, which is where they have been since early 2009. They look like remaining there for the rest of this year, and one MPC member – Andy Haldane, the Bank’s chief economist – says he can contemplate voting to cut borrowing costs.

That’s because there’s a potential dark side to the fall in inflation, namely the risk that it becomes a permanent feature of the economic landscape. The reason the majority of economists view February’s zero inflation as benign is because they think lower unemployment will put upward pressure on wage settlements. Higher pay deals will start to push up inflation at a time when last year’s drop in oil prices starts to unwind. There is, on this view, little prospect of deflation becoming embedded, as it did in Japan.

This, though, assumes that wage settlements are not dragged lower by the drop in inflation. The fact that average earnings are growing at an annual rate of below 2% even after two years of a relatively robust period of growth is indicative of a labour market where employers are able to secure workers cheaply. They may be tempted to be even less generous once inflation goes negative.

Sunday, 19 October 2014

Why did Britain’s political class buy into the Tories’ economic fairytale?

Falling wages, savage cuts and sham employment expose the recovery as bogus. Without a new vision we’re heading for social conflict

The UK economy has been in difficulty since the 2008 financial crisis. Tough spending decisions have been needed to put it on the path to recovery because of the huge budget deficit left behind by the last irresponsible Labour government, showering its supporters with social benefit spending. Thanks to the coalition holding its nerve amid the clamour against cuts, the economy has finally recovered. True, wages have yet to make up the lost ground, but it is at least a “job-rich” recovery, allowing people to stand on their own feet rather than relying on state handouts.

That is the Conservative party’s narrative on the UK economy, and a large proportion of the British voting public has bought into it. They say they trust the Conservatives more than Labour by a big margin when it comes to economic management. And it’s not just the voting public. Even the Labour party has come to subscribe to this narrative and tried to match, if not outdo, the Conservatives in pledging continued austerity. The trouble is that when you hold it up to the light this narrative is so full of holes it looks like a piece of Swiss cheese.

First, let’s look at the origins of the deficit. Contrary to the Conservative portrayal of it as a spendthrift party, Labour kept the budget in balance averaged over its first six years in office between 1997 and 2002. Between 2003 and 2007 the deficit rose, but at 3.2% of GDP a year it was manageable.

More importantly, this rise in the deficit between 2003 and 2007 was not due to increased welfare spending. According to data from the Office for National Statistics, social benefit spending as a proportion of GDP was more or less constant at about 9.5% of GDP a year during this period. The dramatic climb in budget deficit from there to the average of 10.7% in 2009-2010 was mostly a consequence of the recession caused by the financial crisis.

First, the recession reduced government revenue by the equivalent of 2.4% of GDP – from 42.1% to 39.7% – between 2008 and 2009-10. Second, it raised social spending (social benefit plus health spending). Economic downturn automatically increases spending on many social benefits, such as unemployment benefit and income support, but it also increases spending on things like disability benefit and healthcare, as increased unemployment and poverty lead to more physical and mental health problems. In 2009-10, at the height of the recession, UK public social spending rose by the equivalent of 3.2% of GDP compared with its 2008 level (from 21.8% to 24%).

When you add together the recession-triggered fall in tax revenue and rise in social spending, they amount to 5.6% of GDP – almost the same as the rise in the deficit between 2008 and 2009-10 (5.7% of GDP). Even though some of the rise in social spending was due to factors other than the recession, such as an ageing population, it would be safe to say that much of the rise in deficit can be explained by the recession itself, rather than Labour’s economic mismanagement.

When faced with this, supporters of the Tory narrative would say, “OK, but however it was caused, we had to control the deficit because we can’t live beyond our means and accumulate debt”. This is a pre-modern, quasi-religious view of debt. Whether debt is a bad thing or not depends on what the money is used for. After all, the coalition has made students run up huge debts for their university education on the grounds that their heightened earning power will make them better off even after they pay back their loans.

The same reasoning should be applied to government debt. For example, when private sector demand collapses, as in the 2008 crisis, the government “living beyond its means” in the short run may actually reduce public debt faster in the long run, by speeding up economic recovery and thereby more quickly raising tax revenues and lowering social spending. If the increased government debt is accounted for by spending on projects that raise productivity – infrastructure, R&D, training and early learning programmes for disadvantaged children – the reduction in public debt in the long run will be even larger.

Against this, the advocates of the Conservative narrative may retort that the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and that the recovery is the best proof that the government’s economic strategy has worked. But has the UK economy really fully recovered? We keep hearing that national income is higher than at the pre-crisis peak of the first quarter of 2008. However, in the meantime the population has grown by 3.5 million (from 60.5 million to 64 million), and in per capita terms UK income is still 3.4% less than it was six years ago. And this is even before we talk about the highly uneven nature of the recovery, in which real wages have fallen by 10% while people at the top have increased their shares of wealth.

But can we not at least say that the recovery has been “jobs-rich”, creating 1.8m positions between 2011 and 2014? The trouble with this is that, apart from the fact that the current unemployment rate of 6% is nothing to be proud of, many of the newly created jobs are of very poor quality.

The ranks of workers in “time-related unemployment”, doing fewer hours than they wish due to a lack of availability of work – have swollen dramatically. Between 1998 and 2005, only about 1.9% of workers were in such a position; by 2012-13 the figure was 8%.

Then there is the extraordinary increase in self-employment. Its share of total employment, whose historical norm (1984-2007) was 12.6%, now stands at an unprecedented 15%. With no evidence of a sudden burst of entrepreneurial energy among Britons, we may conclude that many are in self-employment out of necessity or even desperation. Even though surveys show that most newly self-employed people say it is their preference, the fact that these workers have experienced a far greater collapse in earnings than employees – 20% against 6% between 2006-07 and 2011-12, according to the Resolution Foundation – suggests that they have few alternatives, not that they are budding entrepreneurs going places.

So, in between the people in underemployment (6.1% of employment) and the precarious newly self-employed (2.4%), 8.5% of British people in work (or 2.6 million people) are in jobs that do not fully utilise their abilities – call that semi-unemployment, if you will.

The success of the Conservative economic narrative has allowed the coalition to pursue a destructive and unfair economic strategy, which has generated only a bogus recovery largely based on government-fuelled asset bubbles in real estate and finance, with stagnant productivity, falling wages, millions of people in precarious jobs, and savage welfare cuts.

The country is in desperate need of a counter narrative that shifts the terms of debate. A government budget should be understood not just in terms of bookkeeping but also of demand management, national cohesion and productivity growth. Jobs and wages should not be seen simply as a matter of people being “worth” (or not) what they get, but of better utilising human potential and of providing decent and dignified livelihoods. Ways have to be found to generate economic growth based on rising productivity rather than the continuous blowing of asset bubbles.

Without a new economic vision incorporating these dimensions, Britain will continue on its path of stagnation, financial instability and social conflict.

Wednesday, 2 July 2014

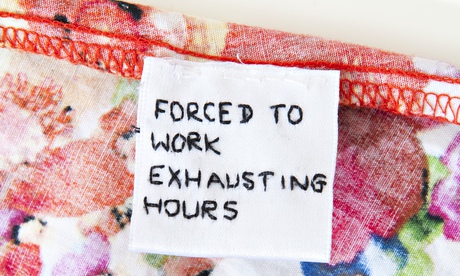

Why we need a Truth on the Clothes Label Act

We know more about the conditions of our battery hens than of our battery textile workers. A year after Rana Plaza, it's time we were given the facts

'Forcing businesses to admit exactly who is responsible for their economic success, and who reaps the profits, is a good start'. Illustration: Daniel Pudles

Somewhere in Swansea is a woman whose hand I want to shake. My guess is that she's the one responsible for giving Primark such a stonking headache over the past few days. You probably know her handiwork – at least, you will if you saw the stories about how two Swansea shoppers came back from the local Primark with bargain dresses mysteriously bearing extra labels. One read "'Degrading' sweatshop conditions"; another "Forced to work exhausting hours".

How did they get there? "Cries for help" from a production line in deepest Dhaka, claim the merchants of journalese. But surely no machinist could bunk off their punishing workload to script these complaints in pristine English, stitch them in and whisk them past a pin-sharp inspector. The much-more-likely scenario is an activist, holed up in a south Wales fitting room, hastily darning her protests.

In which case: well-needled, that woman. Not only has she gummed up the Primark publicity machine for days on end and brought back into discussion the costs of cheap fashion, she's also given pause to two shoppers. In the words of one: "I've never really thought much about how the clothes are made … I dread to think that my summer top may be made by some exhausted person toiling away for hours in some sweatshop."

In a mall, such thinking counts as disruptive activity. The lexicon for most retailers runs from impulse buy to splurge to treat; they prefer us to wander the aisles with our eyes wide open and our minds shut tight. The whole point of a shopping environment is to drown out those inconvenient headlines about dead textile workers in Rana Plaza with a bit of Ellie Goulding and a lot of advertising. Which is what makes the Primark protests, or the Tesco shelfie campaign, or the UK Uncut rallies so splendidly aggravating – because they undercut the multimillion-pound marketing with point of sale information about poverty pay for shop staff or high-street tax dodging.

They also underline how little we're told about what we're paying for. Look at the label sewn into your top: the only thing it must tell you under law is which fibres it's made out of – whether it's cotton or acrylic or whatever. Which country your shirt came from, or the accuracy of the sizing – such essentials are in the gift of the retailer. A similarly light-touch regime holds for food: after years of fighting between consumer groups and the (now eviscerated) Food Standards Agency, and big-spending food manufacturers, a new set of traffic-light labels will be introduced. Thanks to heavy industrial lobbying, it will still be completely voluntary.

How much sugar is in your bowl of Frosties: this is a basic fact, yet it remains up to the seller how they present it to you. By law you are entitled to more information about the production of your eggs than your underwear. Under current regulations, we know more about our battery hens than we do about our battery textile workers.

A ‘cry for help' label in a top from Primark in Swansea. ‘Big retailers can also display prominently how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.' Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Wales News Service

A ‘cry for help' label in a top from Primark in Swansea. ‘Big retailers can also display prominently how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.' Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Wales News Service

Consider: just over a year has passed since the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory, which saw more than 1,100 staff crushed to death and another 2,500 injured, many permanently disabled. Those people and the thousands of others working in similarly precarious and punishing conditions make the garments we wear and the electronic goods we fiddle about with. Yet they rate barely a mention. Outsourcing and globalisation may have brought down the price of our shopping, but it has also enabled retailers to engage in a facade of blame-shifting and plausible deniability: for Apple to pass the buck for suicidal Chinese workers on to Foxconn and duck the questions about how much of a margin it pays suppliers.

So here's a modest proposal: a new law that mandates more, and more relevant information, on the products we buy. Call it the Truth on the Label Act, which will require shops to display where their goods are made, which chemicals were used in production, and whether the factory is unionised. Stick it on the shelves, print it on the clothes tags. Big retailers can also display prominently in each branch how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.

That's because while queuing up for the self-service checkout, hungry commuters might want to know that the boss of Tesco's, Philip Clarke, is paid 135 times what his lowest-paid member of staff is. Or that George Weston, chief executive of Primark's parent company, received over £5m last year, while the young women who sew his firm's T-shirts get less than £30 a month.

Such information is not hard for the big retailers to provide. Long before Google was an algorithm in a programmer's eye, Tesco was in the data-collection business. This information in itself won't change an entire economic system. But forcing businesses to admit exactly who is responsible for their economic success, and who reaps the profits, is a good start. Otherwise, we're entirely dependent on activists in changing rooms.

Monday, 23 December 2013

There's a new jobs crisis – we need to focus on the quality of life at work

British workers face low wages, but are also being hurt by job insecurity, stress and the demand of long hours

David Cameron addresses workers at a factory in Britain. ‘The dominant free-market ideology has convinced Britons that consumption is the ultimate goal of life, and that their work is only a means to gaining the income to buy the goods and services to derive pleasure from.’ Photograph: Stefan Rousseau/AFP/Getty Images

With economic growth now picking up and unemployment inching its way downwards, things are beginning to look up for Britain's economy. Except that it does not seem that way to most people.

David Cameron may be in denial, but most people in Britain are experiencing a "cost of living crisis", as Labour puts it. Growth in nominal wages has failed to keep up with the rise in prices. With real wages predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility not to recover to the pre-crisis level until 2018, we are literally in for a "lost decade" for wage earners in Britain.

Worse, the crisis for British wage-earners is much more than the cost of living. It is a work crisis too. Take unemployment. For most people this results in a loss of dignity, from the feeling of no longer being a useful member of society. When combined with economic hardship, this loss makes the jobless more likely to suffer depression and even to take their own lives, as starkly shown by Sanjay Basu and David Stuckler in The Body Economic. There is even some evidence, published in the British Medical Journal, thatout of work people become more prone to heart diseases. Unemployment literally costs human lives.

On this account British workers have been doing badly since the financial crisis began. Though the unemployment rate has fallen, it still stands at 7.4%. Most people find this rate acceptable, if regrettable – but that is only because they've been taught to believe that full employment is impossible. We may not be able to go back to the mid-1960s and the mid-70s, when the jobless rate was between 1% and 2%, but a rate much lower than today's is possible, if we had different economic policies.

There is also the issue of job security. The feeling of insecurity is inimical to our sense of wellbeing, as it causes anxiety and stress, which harms our physical and mental health. It is no surprise then that, according to some surveys, workers across the world value job security more highly than wages.

On this account too, British workers have been doing very poorly. The rise in the number of zero-hours contracts is only the most extreme manifestation of increasing insecurity for the workforce. The 2010 European Social Survey revealed that a third of British workers feared losing their jobs – giving Britain, together with Ireland, the highest sense of job insecurity in Europe.

Then there's the issue of the quality of work. Even if you are getting the same real wage – which most British workers are not – wellbeing is reduced if your work becomes less palatable. It may have become more strenuous because, say, the company has just turned up the speed of the conveyor belt in the factory, as happened to Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. Or the stress level may have increased because the company reduced your control over your work, as Amazon did when it decided to attach GPS machines to its warehouse staff.

Whatever form it takes, any deterioration in the quality of work can harm the worker's wellbeing. And this is what has been happening to many employees in Britain.

The European Social Survey also revealed that a quarter of British workers have had to do less interesting work. The 2012 Skills and Employment Survey revealed that British employees are now working with much greater intensity than before the crisis; the proportions of jobs requiring high pressure, high speed and hard work all rose significantly from 2006.

And then there is the issue of commuting. Britons spend more hours travelling to and from work than any other workforce in Europe. But to make thing worse, the quality of the commute has been deteriorating. The failure to invest in transport has meant more crowded and more frequently disrupted journeys in many regions of the country. Recent surveys have also revealed that more and more people are working while they commute, at least in part to cope with increased workload.

Once we take into account all these dimensions, it becomes evident that the "cost of living crisis" is only one – albeit important – part of a broader problem that is afflicting most people in Britain.

Despite the graveness of the situation, this wider crisis – perhaps we can call it the "general living crisis" – is not seriously discussed because over the last few decades we have come to neglect work as a serious issue.

During this period, most Britons have come to see themselves mainly – or even solely – as consumers, rather than workers. The dominant free-market ideology has convinced them that consumption is the ultimate goal of life, and that their work is only a means to gaining the income to buy the goods and services to derive pleasure from. At the same time, the decline of the trade union movement has made many people believe that being a "worker" is something of an anachronism.

As a result, policies are narrowly focused on generating higher income, while any suggestion that we spend money on making jobs more secure and work less stressful, if it is ever made, is dismissed as naive. Yet this neglect of work-related life is absurd when most adults of working age devote more than half their waking hours to their jobs – especially if we include the time spent in commuting and, increasingly, out-of-hours work. We simply cannot ignore this when judging how well we are doing.

If we are to deal with the "general living crisis" we need to radically change our perspectives on what is a good life. We need to accept that consumption is not the end goal of our life, and stop measuring our wellbeing simply on the basis of earnings. We need to explicitly take the quality of our work-related life into account in judging our wellbeing. Let's start taking work seriously.

Saturday, 16 November 2013

If Labour want to start apologising, it shouldn't be over economic migration

Jack Straw's admission of guilt over deciding to allow economic migration in 2004 is disingenuous, and sidesteps the real mistakes they made, and the problems we still have as a result

Jack Straw's mea culpa over Labour's 2004 immigration policy is disingenuous, writes Deborah Orr. Photograph: Stefan Wermuth/Reuters

Jack Straw has declared that Labour's decision to allow EU migrants from Poland and Hungary to work in Britain from 2004 was a "well-intentioned policy we messed up" and a "spectacular mistake". It's not quite an apology, but at least it's a declaration of fallibility. Straw says that inaccurate forecasts from the Home Office, suggesting far fewer people would come to the UK than id, were to blame. So it's not actually Labour's fallibility he's admitting to, really. One can understand why. If Labour started issuing mea culpas, it's hard to see where they would end.

In truth, the "spectacular mistake" of 2004 was not due to a set of duff Home Office figures, and Straw is being disingenuous in saying that it was. It wasn't about the UK's great enthusiasm for the EU either. Countries far more committed to Europe than Britain were more cautious about lifting transitional restrictions on new members. In truth, the decision fitted with Labour's general policy, which was to be enthusiastic about issuing work permits whenever possible. Labour wanted Britain to attract economic migrants. Partly, this was because the larger a working population is, the greater the economic activity, and the more revenue there is to look after those not working – of whom there was a burgeoning number in the UK at that time. But the policy was attractive to Labour for other reasons, too, some of which no Labour government could admit to.

Most glaring was Labour's fear of a resurgence of union power. They didn't want people banding together to insist on higher pay and better conditions. A steady supply of people for whom just working in Britain offered higher pay and better conditions than they would otherwise expect served to reduce cohesion in the workforce, making common purpose harder to achieve. It's easy to see why this was not a perceived benefit of immigration that Labour was keen to advertise, or even explicitly acknowledge within the party.

And anyway, there were further difficult-to-acknowledge complications. At that time, a lot of people in Britain were genuinely unemployable, the effects of the speedy economic restructuring of the 1980s and 1990s having been vastly underestimated by the previous government. Even when new jobs were created, it wasn't easy to pull families and communities that had been thrown on the economic scrapheap off it again.

Norman Tebbit famously exhorted people in areas of high unemployment to get on their bikes and look for work. Economic migrants are, by self-selection, people in a fit state to do so. A migrant workforce is keener, more flexible. But it's hard to inform your electorate of this without sounding as oblivious as Tebbit was to the hopelessness and paralysis that flourishes in ravaged communities. In short, Labour couldn't explain the problems caused by long-term unemployment without sounding as if they were indulging in victim-blame.

Also, Labour had bet the farm on being able to turn round public services systematically starved of investment for years (exacerbating the problems of long-term or inter-generational unemployment). So, in order quickly to recruit, for example, trained and experienced doctors and nurses, Labour went to developing countries to persuade qualified people that they should work in Britain. The awful effect on countries that had invested in training these people, only to have them go elsewhere to work, was a secondary concern. Once again, this is hardly a shining example of international socialism in action.

Nevertheless, economic migration was allowing Labour to do what Cameron, Osborne and their fellow neoliberals still say is impossible. Labour was growing the private sector (mainly in London) at the same time as it was growing the public sector (often outside London). This politically isolated the Conservatives very effectively for a long time, largely because the City, the Institute of Directors and the Confederation of British Industry, theoretically the people whose interests the Tories represented, were the great cheerleaders of Labour's policy on economic migration.

But yet again, Labour couldn't crow too much. "Better at being Tory than the Tories" was not a vote-winning slogan. Yet it was true. The City of London, its wants pandered to, was becoming the largest, most important financial centre in the world, even as the divide between rich and poor, north and south, haves and have-nots was widening. Britain had become so divided that consequences incredibly damaging to one group of people were fantastically advantageous to others. And anything that was advantageous to the wealthy was unchallengeable, as long as taxes were rolling in.

The most obvious of these polarising results is house prices. If you've got a house in London, you have somewhere to live that is also, by happy chance, making a good deal more money each year than the average salary, due only to its continued existence. Out-of-control inflation is generally not considered to be good economic news. Yet, the previous government, like this one, sees rising house prices as the goose that lays the golden eggs. How can they be so blind?

Rising house prices, and a lack of social housing, make London an impossible place even to park your bike, let alone wander off to get a job and a place to live. Only if a young British person's parents live in London, or have a place in London (and why wouldn't they, if they can afford it, London property being such an excellent investment?), does that person stand any chance of making a life in the capital. Of course, since many industries – thanks to lack of union power – now rely on internships for recruitment, getting a job sometimes entails a long period of working for free. So class and regional divisions are ramped up yet more. On it goes.

The most terrible consequence of Labour's political dishonesty is that it provides a foundation for yet more. By failing to admit the extent to which they did the bidding of the private sector – not just on regulation, but by allowing the City to dictate, say, immigration policy, then dressing it up as something more socially progressive – Labour, post-crash, had no defence against the Conservative argument that it was public spending that had caused the crash. Labour was proud of its record on public spending, far more proud than it was of sitting on its hands while house-price inflation ran riot, for example.

Public spending was something that Labour was prepared to admit to, so when the crash came, there Labour was, caught redhanded – except that the real blame lay with Labour's more stealthy policies, policies which, at that late stage, it was politically impossible either to start explaining or apologising for.

But this painful process of explaining and apologising should start in earnest. By bowing to the logic of the free market without explaining that economic migration is simply part of that, Labour has allowed rightwing political rhetoric to continue preaching the lie that global free markets and economic migration are separate issues. Due to Labour's own lies-by-omission, organisations such as the English Defence League and Ukip have been able to flourish. But more urgently, those lies-by-omission have allowed the Conservatives to maintain their own delusions about the efficiency and moral goodness of free markets.

If Jack Straw really thinks that allowing people from Poland and Hungary to work in Britain was a "spectacular mistake", I dread to imagine the level of hyperbole he would have to achieve in order to describe the magnitude of the many mistakes his government made, of which that one was just a tiny detail.

Friday, 8 November 2013

Decent wages or a breadline economy: it's a no-brainer

The hostility that greeted Ed Miliband's ideas about increasing pay epitomises everything that's wrong with British business

Labour leader Ed Miliband delivers a speech on Labour's plans to tackle low pay, at Battersea Power Station in London. Photograph: Stefan Rousseau/PA

Ed Miliband's speech at Battersea power station in London on Tuesday this week attracted a lot of attention. Not least because of the Labour leader's own choice of battleground for the 2015 election, the debate has focused on his ideas about wages: his proposal to raise minimum wages in sectors such as finance, and to provide tax breaks for firms that pay living wages.

The reactions have been predictable. Many people are up in arms against the very idea that the government may "artificially" raise wages through market intervention. Many, including a former adviser to Tony Blair, solemnly warn that this will create unemployment and hurt British companies – or, to be more precise, companies that operate in Britain, as so few are owned by British citizens nowadays.

A typical reaction came from John Cridland, the director general of the CBI, who said in a BBC interview that employers "pay what they can afford to pay, depending on the income they get from the consumers". In this short sentence, Cridland – befitting his status as the spokesman for British business – has unwittingly managed to epitomise what is wrong with British business today.

To begin with, the argument shows the disingenuousness with which many large British companies describe themselves as helpless prisoners of market forces. It implies that the incomes companies get from their consumers are beyond their control, because they cannot charge their customers more than their competitors do.

But many companies do in fact have significant influence over what they charge (known technically as "market power"). It may be because they face little competition, like the railway companies. They may, like the payday loan companies, be dealing with poor customers in desperate situations. It may even be that they actively collude, like the big banks in the Libor scandal, or act in concert, like the energy companies in their recent price rises. Whatever the reason, it is simply not true that these companies have to take whatever customers give them.

So at least companies with market power are perfectly capable of paying their workers more by charging customers more, if they so wanted – except that they don't. Many are busy using the profits from overcharging customers to give big pay rises to their CEOs and give away money to their shareholders. Between 2001 and 2010, the top 86 UK companies included in the Europe 350 index distributed 88% of their profits to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks. Naturally, there is no money left for the workers.

More problematic than this misrepresentation of big business is Cridland's view – shared by many in business, government and media – that British companies cannot "afford" to pay higher wages. The subtext is that British companies have to compete with companies from low-wage countries like China, so British workers should feel lucky they are not paid even less, to match Chinese wages. In this view, whatever causes wages to rise needs to be abolished or at least seriously weakened: trade unions, health and safety regulations (the new whipping boy of the Tory right) or employers' national insurance contributions.

In the short term it may be true that raising wages hurts competitiveness, especially if you are a small company with no market power. However, even in this case the effects of higher wages may be offset by savings from reduced staff turnover and the improved efficiency of happier workers – as Miliband rightly pointed out.

In the long run, however, companies and countries should not be afraid of higher wages. If anything, higher wages are signs of success. They are proof that you are more productive than your competitors, so nations and enterprises should strive to pay higher wages in the long run.

Workers in German car factories are paid about 30 times more than their Chinese counterparts, and twice what their American "competitors" get. Despite that, German car companies more than match their Chinese and even US rivals.

One thing that enables German companies to stay ahead of the game is that Germany as a country has invested heavily in technical education and training, making its workers individually more productive than their foreign counterparts. A more important reason, however, is that German workers benefit from more productive technologies as a result of the investments that German companies have made in advanced machinery and research and development. It is exactly because British companies have not made similar investments that they "cannot afford" to pay their workers good wages.

The low-wage strategy so beloved of the British business elite – or what Miliband called the "race to the bottom" – has no future. If Britain is aiming to compete with China in terms of wages, it will have to lower them by 85%. It is doubtful whether this can be achieved even if it engineers a 30-year recession and installs the harshest military dictatorship. Worse, once it had reduced its wages to the Chinese level, it would have to contend with Vietnam, where wages are one-quarter those of China's. After dealing with Vietnam, Britain would have to face down the Ethiopias and Burundis of this world, with wages one-third that of Vietnam's, or less. Countries like Britain can never win that game.

Does Britain want to go back to Victorian times or, looking forward, become like some Middle East oil states, where a small wealthy minority is served by poorly paid workers with zero-hour contracts and minimal rights? Or does it want to reform its economic system so that its companies and government invest in raising productivity – and thus enable its workers to have decent wages, job security, and well-protected rights?

The choice seems like a no-brainer. Unfortunately, large sections of the British business and political establishment do not see it that way.

Tuesday, 2 April 2013

Communism, welfare state – what's the next big idea?

Any attempt to challenge the elite needs courage, inspiration and a truly ground breaking proposal. Here are two to set us off

Maria Bgor and her daughter wait for emergency food supplies at the Mosaic church food bank in Hillfields, Coventry. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Most of the world's people are decent, honest and kind. Most of those who dominate us are inveterate bastards. This is the conclusion I've reached after many years of journalism. Writing on Black Monday, as the British government's full-spectrum attack on the lives of the poor commences, the thought keeps returning to me.

"With a most inhuman cruelty, they who have put out the people's eyes reproach them of their blindness." This government, whose mismanagement of the economy has forced so many into the arms of the state, blames the sick, the unemployed, the underpaid for a crisis caused by the feral elite – and punishes them accordingly. Most of those affected by the bedroom tax, introduced today, are disabled. Thousands will be driven from their homes, and many more pushed towards destitution. Relief for the poor from council tax will be clipped; legal aid for civil cases cut off. Yet at the end of this week those making more than £150,000 a year will have their income tax cut.

Two days later, benefit payments for the poorest will be cut in real terms. A week after that, thousands of families who live in towns and boroughs where property prices are high will be forced out of their homes by the total benefits cap. What we are witnessing is raw economic warfare by the rich against the poor.

So the age-old question comes knocking: why does the decent majority allow itself to be governed by a brutal, antisocial minority? Part of the reason is that the minority controls the story. As John Harris explained in the Guardian, large numbers (including many who depend on it) have been persuaded that most recipients of social security are feckless, profligate fraudsters. Despite everything that has happened over the last two years, Rupert Murdoch, Lord Rothermere and the other media barons still seem to be running the country. Their relentless propaganda, using exceptional and shocking cases to characterise an entire social class, remains highly effective. Divide and rule is as potent as it has ever been.

But I've come to believe that there's also something deeper at work: that most of the world's people live with the legacy of slavery. Even in a nominal democracy like the United Kingdom, most people were more or less in bondage until little more than a century ago: on near-starvation wages, fired at will, threatened with extreme punishment if they dissented, forbidden to vote. They lived in great and justified fear of authority, and the fear has persisted, passed down across the five or six generations that separate us and reinforced now by renewed insecurity, snowballing inequality, partisan policing.

Any movement that seeks to challenge the power of the elite needs to ask itself what it takes to shake people out of this state. And the answer seems inescapable – hope. Those who govern on behalf of billionaires are threatened only when confronted by the power of a transformative idea.

A century and more ago the idea was communism. Even in the form in which Marx and Engels presented it, its problems are evident: the simplistic binary system into which they tried to force society; their brutal dismissal of anyone who did not fit this dialectic ("social scum", "bribed tool[s] of reactionary intrigue"); their reinvention of Plato's guardian-philosophers, who would "represent and take care of the future" of the proletariat; the unprecedented power over human life they granted to the state; the millenarian myth of a final resolution to the struggle for power. But their promise of another world electrified people who had, until then, believed that there was no alternative.

Seventy years ago, in the UK, the transformative idea was freedom from want and fear through the creation of a social security system and a National Health Service. It swept a Labour government to power which was able, despite far tougher economic circumstances than today's, to create a fair society from a smashed, divided nation. This is the achievement which – through a series of sudden, spectacular and unmandated strikes – Cameron's government is now demolishing.

So where do we look for the idea that can make hope more powerful than fear? Not to the Labour party. If Ed Miliband cannot bring himself even to oppose a bill which retrospectively denies compensation to cheated jobseekers, the most we can expect from him is a low-alcohol conservatism of the kind that doused all aspiration under Tony Blair.

Last week I ran a small online poll, asking people to nominate inspiring, transfiguring ideas. The two mentioned most often were land value taxation and a basic income. As it happens, both are championed by the Green party. On this and other measures, its policies are by a long way more progressive than Labour's.

I discussed land value taxation in a recent column. A basic income (also known as a citizen's income) gives everyone, rich and poor, without means-testing or conditions, a guaranteed sum every week. It replaces some but not all benefits (there would, for instance, be extra payments for pensioners and people with disabilities). It banishes the fear and insecurity now stalking the poorer half of the population. Economic survival becomes a right, not a privilege.

A basic income removes the stigma of benefits while also breaking open what politicians call the welfare trap. Because taking work would not reduce your entitlement to social security, there would be no disincentive to find a job – all the money you earn is extra income. The poor are not forced by desperation into the arms of unscrupulous employers: people will work if conditions are good and pay fair, but will refuse to be treated like mules. It redresses the wild imbalance in bargaining power that the current system exacerbates. It could do more than any other measure to dislodge the emotional legacy of serfdom. It would be financed by progressive taxation – in fact it meshes well with land value tax.

These ideas require courage: the courage to confront the government, the opposition, the plutocrats, the media, the suspicions of a wary electorate. But without proposals on this scale, progressive politics is dead. They strike that precious spark, so seldom kindled in this age of triangulation and timidity – the spark of hope.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)