As dusk falls in the Girlington district of Bradford, a trickle of cars begin to arrive in front of a small parade of shops. Parents who have just collected their children at the end of the school day are dropping them off at the Explore Learning tuition centre for extra maths and English coaching. The children sit at a cluster of computer terminals, where they log in to begin their evening studies. The atmosphere is relaxed and lighthearted. The children stay for an hour to work through their lessons, helped where necessary by a member of staff, with 15 minutes’ playtime at the end.

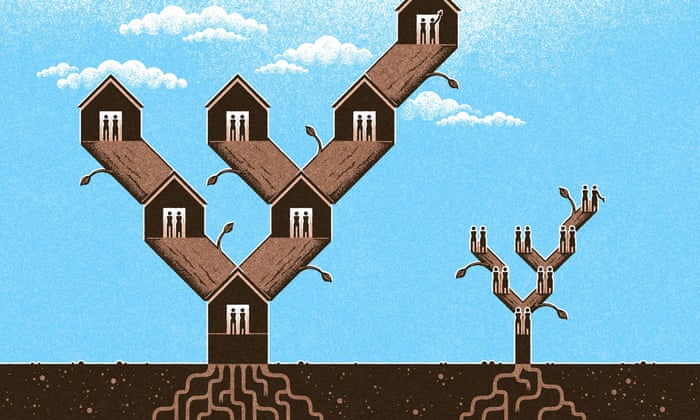

Located next to a Domino’s and a Subway, the Bradford branch of Explore Learning is a tiny window into Britain’s booming private tuition sector, now worth an estimated £2bn. At one time, private tuition meant a weekly one-to-one session at home with a tutor, the preserve of the privileged few. It is still not cheap – Explore Learning’s standard membership costs £119 a month, plus a £50 registration fee – but it is now on offer on our high streets, in supermarkets and increasingly online, with tutors offering their services from as far afield as India and Sri Lanka. Tutees include children who are little older than toddlers, pupils at prestigious private schools and undergraduates struggling at university. All are caught up in an educational arms race, which experts say is exacerbating social inequality.

The success of Explore Learning reflects some of these changes. The business was founded in 2001 by Bill Mills, a Cambridge maths graduate, and now has 139 centres around the country (plus five in Texas run by a sister company). They are located mainly in shopping centres, so busy parents can get on with their weekly shop while their offspring perfect their times tables, punctuation and grammar. Most of the children, who are aged four to 14, come at least a couple of times a week – the membership allows for up to nine sessions a month. Saturday and Sunday afternoons are the busiest times in the Bradford branch, which has 290 children on its books. The tutor-tutee ratio is one to six, but the tutors are not usually qualified teachers; they may be students or mothers returning to the workplace. All are trained in the teaching materials and behaviour management.

The families who use the centre come from various walks of life. Some parents have their own businesses; others work at Bradford Royal Infirmary. There are families from Latvia, Poland and the Philippines. The parents talk about giving their children “an edge”, the “leg up” they never had. Among them are a shift worker, Malik Ijaz, and his wife, Ayesha, who have been bringing nine-year-old Abubakar and his seven-year-old sister, Amna, to the centre for nearly two years. It is a big expense for the family, but the children’s education is a priority. Ijaz works extra shifts to be able to afford it. A third child, four-year-old Ali, will come when he is older.

Located next to a Domino’s and a Subway, the Bradford branch of Explore Learning is a tiny window into Britain’s booming private tuition sector, now worth an estimated £2bn. At one time, private tuition meant a weekly one-to-one session at home with a tutor, the preserve of the privileged few. It is still not cheap – Explore Learning’s standard membership costs £119 a month, plus a £50 registration fee – but it is now on offer on our high streets, in supermarkets and increasingly online, with tutors offering their services from as far afield as India and Sri Lanka. Tutees include children who are little older than toddlers, pupils at prestigious private schools and undergraduates struggling at university. All are caught up in an educational arms race, which experts say is exacerbating social inequality.

The success of Explore Learning reflects some of these changes. The business was founded in 2001 by Bill Mills, a Cambridge maths graduate, and now has 139 centres around the country (plus five in Texas run by a sister company). They are located mainly in shopping centres, so busy parents can get on with their weekly shop while their offspring perfect their times tables, punctuation and grammar. Most of the children, who are aged four to 14, come at least a couple of times a week – the membership allows for up to nine sessions a month. Saturday and Sunday afternoons are the busiest times in the Bradford branch, which has 290 children on its books. The tutor-tutee ratio is one to six, but the tutors are not usually qualified teachers; they may be students or mothers returning to the workplace. All are trained in the teaching materials and behaviour management.

The families who use the centre come from various walks of life. Some parents have their own businesses; others work at Bradford Royal Infirmary. There are families from Latvia, Poland and the Philippines. The parents talk about giving their children “an edge”, the “leg up” they never had. Among them are a shift worker, Malik Ijaz, and his wife, Ayesha, who have been bringing nine-year-old Abubakar and his seven-year-old sister, Amna, to the centre for nearly two years. It is a big expense for the family, but the children’s education is a priority. Ijaz works extra shifts to be able to afford it. A third child, four-year-old Ali, will come when he is older.

‘I’m trying to do something for him that I never got’ ... Geoff Clayton, Brooklyn’s grandfather. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

“The world is very competitive and everybody is working very hard,” said Ijaz. “I know the school are doing very well, but there are 30 students in each class. It’s one teacher and support staff. They try their best to help, but I realise if I’m going to give my kids some extra help it’s going to be brilliant for their future. Anyone who does a bit extra always gets ahead.”

He is ambitious for his children. “I warn my kids they should be top – or among the top five at least – in class. They are doing well. I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future. I know the importance of education. My kids love it.”

Abubakar, a quiet, serious child, is planning to sit the 11-plus to win a place at grammar school. Sometimes he does not feel like starting work, “but when I’ve started I like to carry on”. Amna is a chatty livewire and wants to be a paleontologist. “I’m good at maths, but the thing I’m best at is history,” she chirps. “My brother does hard work. I’m doing the same now. I want to be the same as him.”

Geoff Clayton, a retired garage worker, has been bringing his 10-year-old grandson, Brooklyn, to Explore Learning for about nine months. Brooklyn lives with his grandparents and likes football, Minecraft and maths. “He’s done really well,” says Clayton. “His reading has got a lot better, everything’s got better.” The membership takes a significant chunk out of his pension, but he is happy to pay it to give Brooklyn “a bit of a leg up”.

“Nowadays, it’s all about exams and certificates and what you know,” he says. “When I left school, it was more: ‘Can you do the job?’ Brooklyn has done a heck of a lot better since coming here. Sometimes he moans, but he’s OK once he’s here. It does work if you’re prepared to put the time and effort in.”

The Sutton Trust, a charity that seeks to improve social mobility through education, has documented a huge rise in private tuition in recent years. Its annual survey of secondary students in England and Wales revealed in July that 27% have had home or private tuition, a figure that rises to 41% in London.

The Bradford outpost of Explore Learning, which now has 139 centres across the UK. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

With tutoring commanding a fee of about £24 an hour, rising to £27 in London (although many tutors charge £60 or more), the trust is concerned that the private tuition market is putting children from poorer backgrounds at even greater disadvantage. To redress the balance, it would like to see the government introduce a means-tested voucher system, paid for through the pupil premium funding that schools receive to support disadvantaged pupils.

“We are in an education arms race,” says Peter Lampl, the founder of the trust. “Parents are looking to get an edge for their kids and having private tuition gives them that edge. But if we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure that the academic playing field is levelled outside the school gate.”

Initiatives aimed at making tuition more accessible already exist: some agencies pledge a proportion of their tuition to poorer pupils for free, while non-profit programmes such as the Tutor Trust connect tutors with disadvantaged schools. Explore Learning offers “scholarships” that give a 50% discount to parents on income support or jobseeker’s allowance. Parents can also use childcare vouchers and tax-free childcare schemes to help pay for tuition.

Nevertheless, huge inequities in education persist. Nowhere is this more evident than in children’s battle to pass the 11-plus to get into grammar school. Research published earlier this year revealed that private tutoring means pupils from high-income families are much more likely to get into grammar schools than equally bright pupils from poorer families. John Jerrim and Sam Sims from the Institute of Education at University College London looked at more than 1,800 children in areas where the grammar school system is in operation. They found that those from families in the bottom quarter of household incomes in England have less than a 10% chance of attending a grammar school, compared with a 40% chance for children in the top quarter.

If we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure the academic playing field is levelled outside school - Peter Lampl, the Sutton Trust

They also established that wealthier families are much more likely to use private tutors to prepare their children for the entrance exam. Fewer than 10% of children from families with below-average incomes received coaching, compared with about 30% from households in the top quarter. About 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared with 14% of those who did not.

Alexa Collins lives in Buckinghamshire, which operates a grammar school system. She could not afford tuition to prepare her daughter for the 11-plus; despite being a top performer at primary, she failed the test, but has since thrived at her comprehensive, gaining nine GCSEs.

Collins, who went to grammar school herself but received no coaching, says she is ideologically opposed to tutoring because it is unfair to those who cannot afford it. Although she can see the case for short-term tutoring on a specific subject when a child is struggling, she adds: “I think it’s awful, that idea of tutoring kids from seven to push them through this exam. How can you possibly put that pressure on them?”

Another parent, who wishes to remain anonymous but lives in Kent, which operates grammar schools, says her son tackled the 11-plus without a tutor. “It felt morally wrong to claim an advantage by paying cash. It’s so unfair.” As she tried to coach her son, she felt at huge disadvantage. “So much depends on a parent’s skills to teach. A tutor would know the best way to teach the 11-plus concepts. I was terrible at maths at school, so I was really stuck.”

“The government claims that expanding grammars will boost social mobility,” said Jerrim, a professor of education and social statistics at UCL, when the research was published. “But our research shows that private tuition used by high-income families gives them a big advantage in getting in.” One of the factors behind the increase in tuition, he says now, is the pressure exerted by school league tables and growing accountability measures. “Those schools might well be passing pressure on to parents,” he says. “It’s not a negative reflection on schools and the job that they are doing; it’s more a reflection of the pressure they are under to achieve results.”

A callout asking Guardian readers about their experiences of tuition drew hundreds of responses from tutors, parents and school teachers. One tutor told of being approached by parents of children as young as three or four; another had been hired to provide extra coaching for pupils whose parents were already paying for all of the privileges of private schools, including Marlborough and Eton. “We pay thousands of pounds a year on school fees,” said one parent. “If he needs a little help with certain subjects, why wouldn’t you help him?” There also appears to be a trend for university students to buy extra tuition. Most are already paying £9,250 a year in tuition fees, so why not spend a little more to ensure they get the best possible degree?

The Profs, which launched in 2014, specialises in degree-level and professional-qualification tutoring. According to its website, an undergraduate teacher with a master’s in the required subject costs upwards of £70 an hour (plus a £50 placement fee); tutors specialising in applications to Oxbridge and Ivy League universities start at £120 an hour, plus a £250 consultation fee. According to Leo Evans, one of the founders of The Profs, university lecturers can struggle to address individual learning difficulties. “Catching stragglers and helping them get on top of their studies is a useful social function. Also, for students with disabilities and impairments, it’s essential.”

I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future’ ... Malik Ijaz and his wife, Ayesha, bring a son and a daughter to the Bradford classes. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Guardian

Other responses to our callout came from parents who were worried about schools’ increasingly limited resources due to budget cuts. Much of the additional support that was once available in classrooms is disappearing and some specialist teachers are in short supply. These parents see tutoring as a way of patching the gaps in their children’s education. “It’s only one hour a week, but the practice crammed into that time is like a full week of lessons at school,” said one parent, who is a teacher. “The ability to check every week how well the information is being retained is great. It also provides ‘real-time’ feedback that we don’t get from schools.”

Some parents buy extra tuition to support children with special educational needs such as dyslexia, which mainstream schools are increasingly unable to meet. The new, tougher GCSE exams are also a factor, with some parents hiring private tutors to help children who are struggling to secure the level 4 or above required in English and maths.

One mother from Nigeria said she sought extra support for her child as a practical response to racial discrimination: “Any child from a minority has to be many times better than their white counterparts to be able to get into the top schools and universities.” Another parent told of a daughter with cancer who missed a year of formal education, but got through with the help of a tutor. Another respondent claimed the shadow tutoring workforce “props up” some “outstanding” schools – private, grammar and state.

Not everyone was positive about the impact of tuition. “It can cause students to not work in lessons,” said one teacher. Another said: “The need for tutoring frightens me. Schools should be able to offer students the support they need in class sizes that are manageable.” While one parent said: “I resent it when having a tutor is seen as a class crime,” another acknowledged the unfairness at the heart of the system: “I feel uncomfortable that we can afford to pay for this privilege.”

The callout also revealed the appeal of private tuition for teachers, whose salaries have been depressed for years while the demands upon them have grown. Some said they did private tutoring to boost their income; others, tired of the one-size-fits-all approach in schools, have quit their jobs to do it full time.

Asked about the boom in private tuition, the Department for Education responded that standards are rising in schools and that the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils is shrinking. “While we believe families shouldn’t have to pay for private tuition, it has always been part of the system and parents have freedom to do this,” a spokesman said.

“Tutoring is huge, it’s getting bigger and it’s not going away,” says the Sutton Trust’s Lampl. “You can’t stop people from doing it. What we’ve got to do is make it more accessible for parents who currently can’t afford it.”

Clayton, the retired garage worker from Bradford, is not a rich man, but he wants to invest what he has in his grandson’s future. His hopes for Brooklyn are modest and honourable and shared by parents and grandparents everywhere. “I want Brooklyn to have a good start in life … Nobody gave me a leg up. I’m trying to do something for him that I never got. I hope he ends up being a decent person when he grows up and gets a decent job and doesn’t have to struggle.”