The full transcript of Jonathan Derbyshire’s interview with renowned Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen

Amartya Sen

Jonathan Derbyshire: We first met four years ago. You said something to me then that I think bears on the preoccupations of your new book, co-written with Jean Drèze, An Uncertain Glory. We were talking about the Indian left. You said: “I’ve been very critical of the political balance of the left in India in recent years. A party which has a real commitment to the underdogs of society should be much more worried than it seems to be that India has a higher proportion of undernourished kids than anywhere else in the world.” That insight is, more or less, the point of departure for your new book isn’t it? You’re interested, in other words, in what you call the “two-way relationship” between “social justice” (your term) and economic growth, which of course has been spectacular in India over the past 15-20 years.

Amartya Sen: That’s exactly right. At the time, I hadn’t done the systematic work to see what the other indicators looked like, but I knew that on the undernourishment index we [ie India] were very low. But then when I found that this was true in other many other aspects – having a stable and secure medical arrangement for all; having a well functioning school system to which every child has actual access; universal coverage of immunisation – in all these areas India seemed to be doing worse than many countries which it has overtaken in terms of per capita income- for example, Bangladesh. So this, four years ago, was a thought that was bothering me which I always wanted to follow up. As I looked through it with my friend and collaborator Jean Drèze, it became clear that systematically India was underperforming in these respects, even when it was outperforming other large economies, with the exception of China (today, despite its fall in growth rate, it still has the third highest rate of growth among large economies, after China and Indonesia).

JD: That context – the competition with China and the other BRIC nations, India’s sense of itself as punching its weight on the global stage – matters doesn’t it?

AS: Yes. Economic growth is important precisely because it can help people to lead better lives, but to take growth itself to be a fetishistic object of admiration is part of the problem. We may legitimately worry about the slowing of Indian growth that is happening compared to, say, Indonesia. But we have to ask the right questions and note, for example, the importance of the fact that Indonesia has a higher ratio of literacy, education, higher ratio of secure healthcare. I think we have to understand that ultimately not having an educated, healthy population is not only bad for well-being but also bad in the long run for sustaining our economic growth.

JD: A question about the theoretical framework of the book. You said you started from a number of empirical observations about these indices (healthcare, literacy and so on) in which India was doing much worse than countries that it was outstripping in terms of GDP growth. I wondered whether your notion of “capabilities” is shaping your approach here (access to healthcare, education etc being “capabilities” that make human lives go better rather than worse).

AS: Yes, it’s very important for two different reasons. The first reason is that in order to judge how a country is doing you can’t just talk about per capita income. India used to be 50 per cent richer than Bangladesh in per capita income terms but is now 100 per cent richer. Yet, in the same period … when, in the early 1990s, India was three years ahead of Bangladesh in life expectancy, it is now three or four years behind. In India it is 65 or 66, in Bangladesh it’s 69. Similarly, immunisation: India is 72 per cent, Bangladesh is more like 95 per cent. Similarly, the ratio of girls to boys in school. So in all these respects, we are looking at capability. We’re looking at the capability to lead a healthy life, an educated life, to lead a secure life (with immunization making people immune to some preventable illnesses), having the capability to read and write, for girls as well as boys.

Expanding and safeguarding human capability is central to thinking about policy making. That understanding informs our work. But what plays a more dialectical role in this book is the insight that many Indian policy analysts may have missed is that human capability is not only important in itself, but that human capability expansion is also a kind of classic Asian way of having sustained economic growth. It started in Japan, just after the Meiji restoration, where the Japanese said: “We Japanese are no different from the Europeans or the Americans; the only reason we’re behind is that they are educated and we are not.” They then had this dramatic expansion in universal education and then, later, widespread enhancement of healthcare. They found that a healthy, educated population served the purpose of economic growth very well. That lesson was later picked up in South Korea. Korea had quite a low educational base at the end of the Second World War. But following Japan, they went in the same direction. The same happened in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and, to some extent, even Thailand. And gradually, in a smaller way, in Indonesia. Of course, they reaped as they had sown. So human capability expansion is very important for Asian economic growth.

This can be seen to be closely related, to use the terms economists seem to prefer, to the importance of “human capital”. I don’t like the term “human capital” very much. Adam Smith says somewhere – it may have been in a letter to Hume – that in this way of talking about human beings, there’s a danger you won’t be able to distinguish between a good human being and a good chest of drawers!

JD: The other central part of the argument in this book concerns democracy and the state of public discourse in India. I think it’s your view that democratic participation is part of the capability set required to live a flourishing human life. Of course, one of the things about the Asian market economies you’ve just discussed, certainly in the 1980s when they experienced the most dramatic growth, is that although they had flourishing civil societies, political participation was actually limited – this is certainly true of Singapore, say, and I think South Korea in that period. How does that sit with the claims you’re making in the book about democracy?

AS: The choice those Asian economies made [to extend healthcare, education etc] wasn’t a democratic choice, but it was a very smart choice. You can be smart without being democratic. However, good practice of democracy – well informed and vigorous – can help to select smart governments, humane governments, and can make those qualities be less fragile and transitory. For this the quality and force of media discussion are important. But if you are lucky enough to have a friendly authoritarian government, they can take smart decisions without having to rely on forceful media discussion. That’s what they did in South Korea and in Taiwan. But North Korea did not. Nor did Cambodia in the 1970s. Democracy can help to make the choice of government not a matter of luck, but of conscious and reasoned public choice. For this to be ensured the opportunities offered by democracy have to be strongly seized. This is where India’s record is divided – excellent use in some areas and very slack use in others. We have to make democratic practice more comprehensive.

Over the decades China has presented examples of good and smart as well as weak and confused authoritarian rule. The gigantic famines of 1958-61 resulted from terrible policy choices that could not be changed for three years despite tens of millions dying each year- no political party could criticize the terrible policies, and newspapers could not even cover the bad news. But after that, despite many other problems, China did remarkably fast progress in education and healthcare for all – an example of good authoritarianism. But they were irrationally prejudiced about the use of markets, which they shunned until the reforms of 1979. With the reforms there were some smart moves (with marketization China did brilliantly in manufacturing and agriculture) but also a big mistake when they marketised health insurance, so you had to buy health insurance rather than being insured by the state or the commune; the Chinese were not alert to the terrible consequences of marketizing everything. The percentage of health coverage went down after 1979 from 100 per cent to 10 or 12 per cent, with downward effects on the high pace of China’s progress in life expectancy. Again, it took them many years to recognise that they had made a mistake, and went about un-doing the harm, a correction that became full speed only in 2004 – a quarter century after the error of marketizing health insurance in 1979. Now they have nearly a hundred percent coverage – and with much better quality health care thanks to China’s economic prosperity.

An authoritarian system, if it is intelligently and humanely led (but there is no guarantee of that), can get its way quickly. A democratic system is somewhat slower, because you have to convince everyone. In the case of India, the question is which issues get dramatised and politicised. Famine was instantly politicised, because it is so central to the Indian view of the British Raj. The Raj began with a famine [in 1769] and ended with a famine [in 1943]. The elimination of famines was an immediate success of democratic India. There have been other successes, particularly when there have been crises – with HIV, for example – when there has been a real sense of urgency, which the media discussion and democratic pressure reflected. Five or ten years ago, people were saying that India was going to have more cases of HIV than anywhere else in the world – not only as an absolute number, but as a proportion. But it hasn’t happened. That challenge was met and things were done to reduce the vulnerability of the population. These challenges received public attention and advocacy, and a democratic success followed.

Unfortunately, the challenge has not been seized in the case of general healthcare, not even general immunisation. And nor has it happened with general education. So I think there is no guarantee that democracy will get there immediately, but it depends on the people to make it happen. And of course the foundational reason for wanting democracy isn’t that. The basic reason for wanting democracy is that it gives people dignity, political freedom, and voice – democracy has its own value. If that is compatible with doing good things, and if what happened with famine and HIV crisis could be translated to general healthcare and chronic undernourishment, then that would be a wonderful combination. There is no reason at all why we- and here I speak as an Indian citizen – cannot make that happen.

JD: You argue that there is a “two-way relationship” between growth, on the one hand, and the expansion of human capability on the other. It’s easy to grasp that point from the side of growth. Could you explain the other side of the argument? How does the expansion of capability enhance growth?

AS: Well, I think the basic insight is that of the Meiji restoration I mentioned earlier – namely that an educated, healthy workforce is very productive. And ultimately it is productivity and skill-formation on which economic and social progress depends. That is the Adam Smithian point. Smith asked “why is trade good?” Trade is good because it allows you to specialise and specialisation allows you to develop skills. He didn’t take the view which can be associated with David Ricardo, that trade is important because of comparative advantage. Smith’s view was that any country could typically produce any good (unless they are unusually geography-dependent). But if you specialise in something you become frightfully good at it – like the Swiss, making chocolate, watches or running banks. Once that happens, then your productivity rises, while in other countries’ productivity rises in other things. Smith also emphasised that general education is something that the state ought to do. He thought it’s a good thing to have an educated population but also that it would help skill-formation.

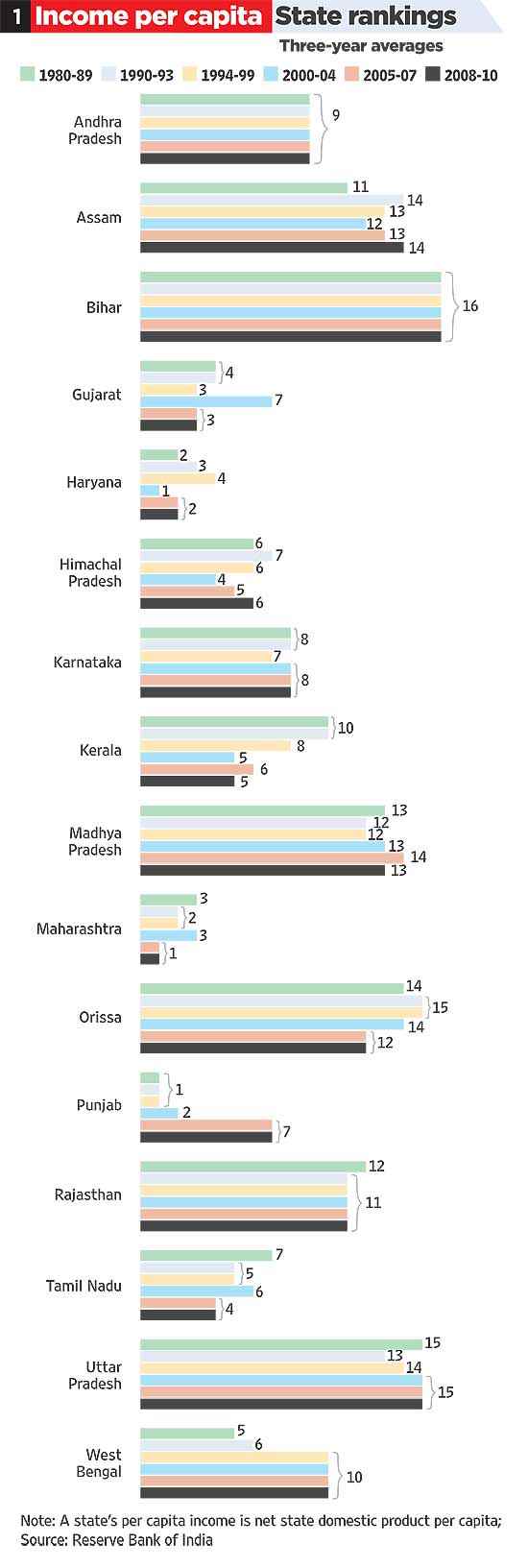

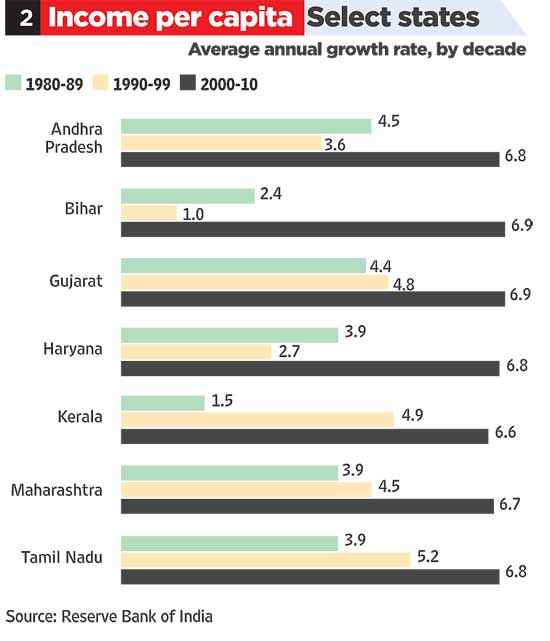

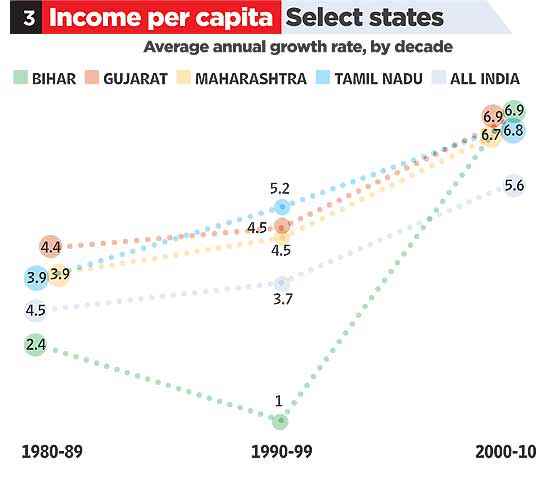

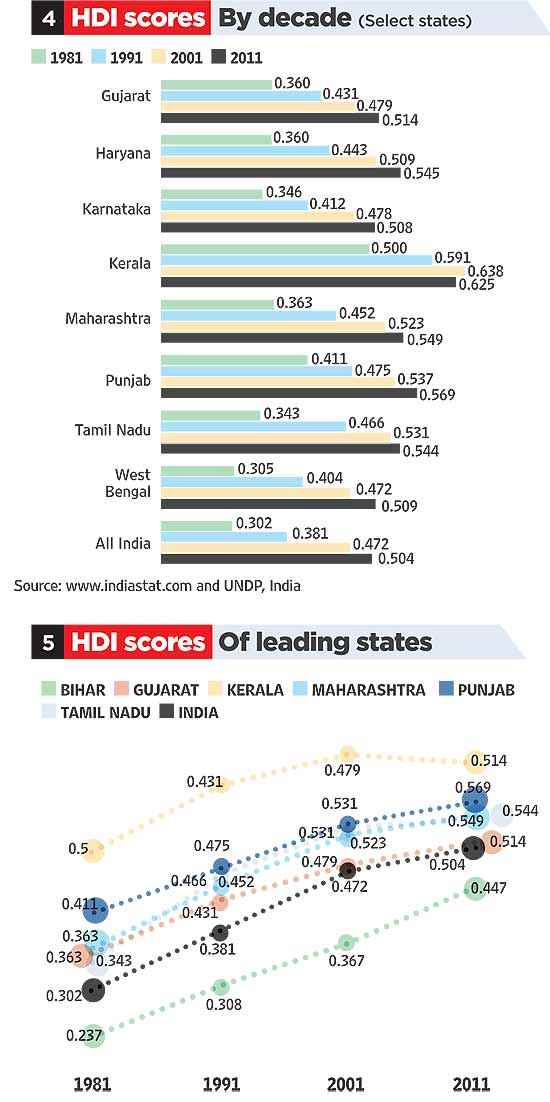

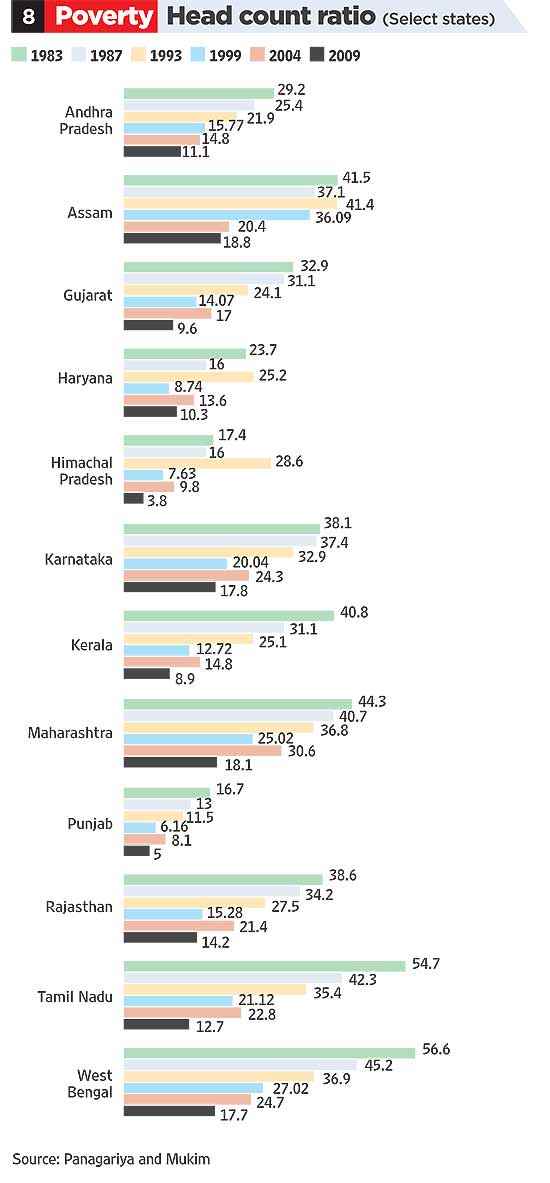

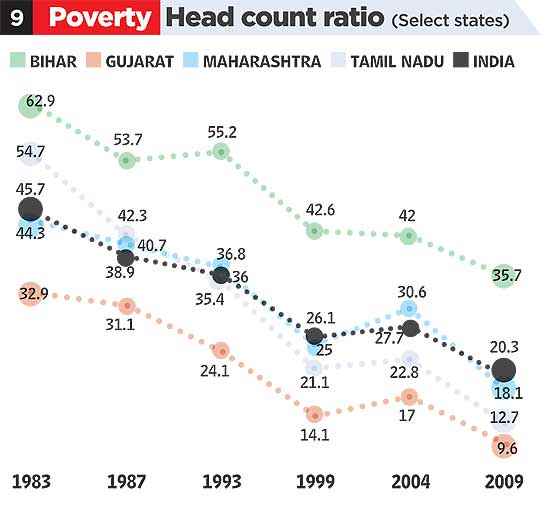

I think that connection the Asian economies saw, and they also saw the central role of skill-formation. Are there studies showing how productivity responds to nourishment, education, healthcare? There are indeed such studies, though we don’t go into a great deal of detail on this in the book. We were going more by the experiences of different countries which have adopted the human development strategy and have all done well. Similarly, states within India – Kerala, for example, which has a faster rate of growth than most others. Every state in India which went in the direction of human capability-formation typically led by the state – think of Tamil Nadu or Himachal Pradesh in addition to Kerala – ended up having a faster rate of economic growth and being ahead. Now some people who earlier were saying that Kerala’s early focus on state-financed education and healthcare could not be sustained now seem to be saying there is nothing to explain! Keralans are rich and therefore have high human capabilities. But that overlooks how they became rich.

JD: So what the other Asian economies show us is that you don’t have to have liberal democratic political institutions in order to have human capability growth?

AS: Yes. But I’ve never denied that.

JD: So what’s the claim about democracy being in this book then?

AS: There are in fact three claims being made. One, that democracy is important in itself, and it is compatible with human capability-based expansion. Two, democratic practice would be deeply favourable to human capability expansion, through good and forceful use. What has been done in the case famine-prevention or HIV-handling can be done more generally through the same practice of democratic pressure. Three, there is no guarantee that you will have human capability expansion with authoritarianism any more than we can be sure about a democracy, except that in the case of a democracy we know how to correct that neglect – in fact through more forceful and informed democratic practice. As the examples I discussed earlier illustrates, while human capability expansion may be well pursued by some authoritarian governments, it may be entirely neglected by other authoritarian rule. With authoritarianism, we do not know whether we would be South Korea or North Korea.

And even when things go well in many ways in an authoritarian state, there is always a fragility [in authoritarian states]: under good rulers you go one way, under bad rulers another. In many ways, Akbar’s India was a benign state, but it depended on the authoritarian rulers having these values. There was nothing in the system that guaranteed it. Democracy doesn’t have that fragility, though it may be harder to get there, slower to get there. For example, consider the fact that one morning in 1979 China abolished universal healthcare – if there had already been universal healthcare in India in 1979, as there was in China, I don’t think any government in India would have been able to abolish that.

JD: How robust do you think Indian democracy is?

AS: Its institutions are robust enough, but its practice is still quite limited. We have to be more vigilant. Gender inequality, long neglected, is a subject that is being taken up much more now, partly because of the terrible incident of rape on 16 December (leading to mass protests). Democracy itself is quite stable in India, but the practice of democracy has been partially vigorous and partially very lethargic. Can we be sure of its vigour? It depends on us – the citizens of the country. Like liberty, democracy requires eternal vigilance.

JD: You distinguish, it seems to me, two questions about democracy. First there’s a question about the compatibility between democracy and growth and you say that question has been definitively settled – we know the two are compatible. The second question is more interesting and difficult to answer and has to do with democracy, on the one hand, and what you call “the use of the fruits of growth for social advancement” on the other. And here the picture is much less clear isn’t it?

AS: Indeed, much less clear. Democracy’s difficulty is that the vocal and the active can influence the agenda in a way that the inactive and unvocal cannot. And the active ones have been the relatively poor among the rich – the bottom 40 per cent of the top 20 per cent (though they’re still part of the top 20 per cent). So, for example, they have asked for a diesel subsidy, and got it; they asked for a cooking gas subsidy and got it; they insisted on electricity being sold to urban consumers at below cost. There have been many other concessions which have cost money. The surplus has gone in their direction because they’ve been more vocal. And what is pernicious, or at least disturbing, is that they speak in the name of “ordinary people”. But ordinary people don’t drive diesel vehicles. Ordinary people don’t have cooking arrangements to which gas cylinders can be attached. And many ordinary people don’t have electricity. Democracy is a guarantee of process. But offers no guarantee as to how that that process will be pursued and what will come of it. If you don’t do anything, you won’t get anything.

JD: Another preoccupation of the book is the contrast between capability growth in India and in China. Presumably that’s a central preoccupation of the India elite? The race with China.

AS: For some parts of the elite. The media gives the impression that the number of people preoccupied with the comparison with China is very large. But it is a relatively small part of the population who read the “pink papers” (the local equivalents of the Financial Times). They are very concerned about this. But I’m not sure it’s an obsessive concern of the Indian elite generally. The literary elite is not very aware of how … they’re quite happy that India is a big player now in literature, in film and in technology. The Indian elite is often under-informed, which is why this book is so information-focused. The business elite is certainly very concerned with the horse race with China without ever asking how India can catch up with China in life expectancy, in literacy, in immunisation. And that’s a bizarre focus.

JD: One aspect of the way India lags behind China is that wage growth in China has far outstripped wage growth in India. Why do you think that is?

AS: First, the bargaining power of workers has been relatively small in India. Also, India has had a high growth rate but based on highly skilled labour – pharmaceuticals, information technology and car parts. But these don’t provide as much employment as you would expect from other industries. As a result, the general competition for labour hasn’t actually occurred. By contrast, a lot of American and European investors in China complain that wages have been rising very fast there. But that’s a sign of success. An economy that’s growing at six, seven or eight per cent a year should not be experiencing wage stagnation of the kind we have in India.

JD: But surely the bargaining power of labour in China is not significantly better in authoritarian China than it is in democratic India?

AS: The bargaining power of labour is better there, definitely. They don’t have unions, certainly, but the unions in India often serve those already relatively better-placed, rather than landless labourers in agriculture or those engaged in other basic unskilled labour. There was a time when the left parties did do that. But since then the more middle-class oriented left parties have been concerned with skilled labour. Skilled labourers’ wages have sometimes risen, but it’s the basic wages of the common labourer which have stagnated. And at that level I think that China does have more competition. But it doesn’t come from the unions – they don’t tolerate unions!

JD: Back to this question about the relationship between GDP growth and capability growth. You know that there is a competing view to yours which says that successful economic development necessarily occurs in two stages – this is a “two-track” account according to which “Track 1” reforms are designed to increase GDP and pull up the poor; healthcare and educational reforms belong to “Track 2”. And that it’s only Track 1 which makes Track 2 possible. You reject that model don’t you?

AS: Well, there’s no historical illustration of that. Japan isn’t. China isn’t. Korea isn’t. Hong Kong isn’t. Taiwan isn’t. Thailand isn’t. Europe isn’t. America isn’t. Brazil isn’t. So what are we drawing that model from? That’s not how things have happened in the world. They’ve all done it through increasing capability. I know of no example of unhealthy, uneducated labour producing memorable growth rates!

JD: What about the charge that you don’t pay as much attention in the book as you might to what one might call the negative externalities of growth and development – principally, the environment and population growth.

AS: On the environment, we do say quite a bit about that in the book, but maybe it’s not adequate – our primary battle was on a different front. Is growth inescapably damaging to the environment? I don’t think so. The biggest influence in reducing the fertility rate, for example, is women’s literacy. The best way of cutting population growth is women’s education, women’s gainful employment. Even in China, the low fertility rate they’ve achieved is explicable entirely by the good things China has done – widespread education of girls, widespread economic independence of women. Anything that increases the voice of young women tends to cut down the fertility rate because the lives that are battered most by the continuous bearing of children are those of young women. So human capability-expansion in the form of education is very environment-friendly in that respect. Now if you want just growth and nothing else, then you may have a clashing course. But if you are concerned with growth and human capability, that’s part of your calculation as to how you can make growth better oriented. It’s a point that Adam Smith makes: we are not concerned commodities themselves; we want them because they allow us to do certain things. If you want to be able to take part in the life of the community and appear in public without shame, then you have to have clothes like those of others. Similarly, if you live in California, you have to have a car to drive around. But what is the point of public reasoning if it doesn’t engage the fact that by having good public transport you can cut down the need for having cars, for example? There is no automatic process by means of which growth itself becomes sustainable without giving thought to it.

JD: We’ve spoken a lot about China. But the book also spends some time on the comparisons between India and another of the BRIC countries, namely Brazil. The account you give of the recent history of Brazil says that what the Brazilians have done in the last 20 years, say, is to correct for what you called “unaimed opulence” with active social policies. Obviously, the book was finished before the current unrest in Brazil began. How are we to understand what is happening in Brazil today? Are we to blame it on sluggish social reform? Probably not, because as you point out, these have been far-reaching. Or do the causes lie elsewhere? Do they lie, for example, in something else you discuss, that is in failures of accountability and corruption in the system?

AS: Yes. Most popular agitations in the world have not been about capability issues. That is the problem we have been discussing in the case of India, too – the cause of the basic education of the common man is not easy to translate into democratic agitation. On the other hand, corruption is; the specific deprivation or organised groups is. Many countries suffer from corruption, including China. Incidentally, those who think India is not growing as fast as China because it’s more corrupt, we don’t know that this is the case. As I’ve said, I think the reason is that they’re dealing with a healthier and better educated population. In the case of Brazil, they are also dealing with a healthier and more educated population. But that’s not what the agitation is about – the protestors aren’t calling for universal healthcare or education. They are talking about corruption and other issues. I think it’s very difficult to judge what’s really going on. Take the Falklands War, which changed the fortunes of Mrs Thatcher completely. It was a minor issue when you think about it. Similarly, there was a kind of massive groundswell to intervene in Iraq in 2002-03, into which initially even very sane voices moved. So I wouldn’t draw any big conclusions on the basis of what is going on in Brazil. By the way, mine isn’t a theory of public agitation. I don’t have a general theory of public discomfort!

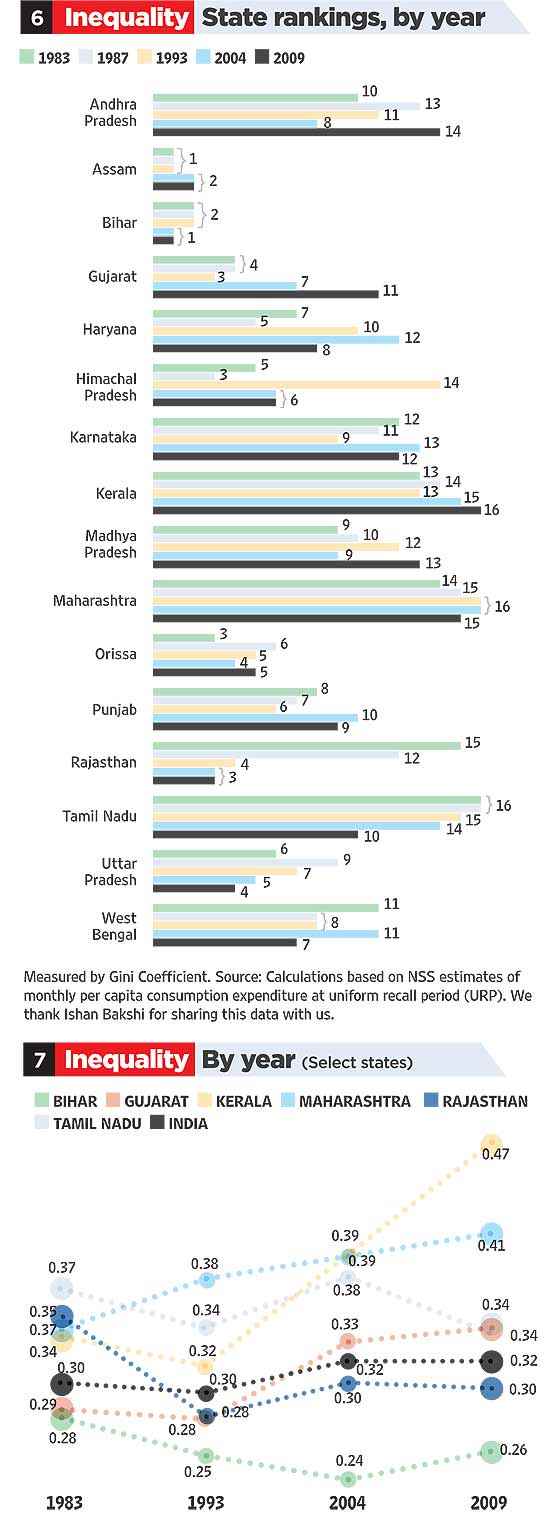

JD: Chapter 8 of the book is devoted to the question of inequality. Could you say something about how in India caste aggravates and exacerbates the economic inequalities that are a feature of all advanced market economies?

AS: It does this in a very big way. First, it is stratification. Second, it is stratification on very hardened lines – it’s not like becoming rich. It’s easier to become bourgeois than it is to become a high-caste Brahmin! Third, there is a kind of approach that has gone along with the caste system, which is that it is a natural order and you can’t change it, and that the alternative is chaos. And that’s quite important to recognise. There are a lot of people who tend to think that undoing the caste system now would be a destabilising course of action. I think caste is about the worst form of inequality you can think of. And the fact that it has gone on for 2,500 years indicates how much of a historical background it has. Class and gender also play a part in Indian inequality. The idea that you need a good school, basic healthcare with a medical unit near where you live, that everyone needs a toilet in their home – these have become more ingrained in many societies, even poor ones, than has been the case in India. You can still build a large condo complex where, given Indian social structures, there will be many servants, without constructing toilets for them. And I think this is a ridiculous failure of vision. So, in that respect, inequality in China, though it is high, is quite different to that in India.

JD: It’s a failure of vision, but not an insuperable obstacle to change? After all, the book ends on an optimistic note.

AS: Yes. In order to get there in a democracy you have to fight for it. There is no way that democracy automatically guarantees that. I first argued that functioning democracies prevent famine in around 1979/80. I think today I would put it slightly differently and say that human beings in a functioning democracy prevent famine. The system in itself wouldn’t do it unless there was activity along with it. In the case of famine, it’s very easy to generate activity. In the case of under-nourishment, less so. We could only make a difference by trying harder.

JD: This invites the question what you mean by “democracy”. As you point out, democracy is about more than free elections. So what’s the ramified notion of democracy at work here?

AS: There are three aspects to it. At some level democracy was to involve majority rule and free voting. That’s the point at which someone like Samuel Huntington would like to stop. I would like to go further. It must also include minority rights, which are part of the institutional structure, and the protection of public discussion – free public discussion, free media and so on. Now, these two requirements are institutional. But the third aspect is not purely institutional – it’s the requirement that people use public reasoning; democracy would be more active the more we use public reasoning in an open way. Now, if the latter doesn’t obtain but the first two do, is it a democracy or not? I won’t go into that debate. I’d say, it is a democracy but it’s not doing very well. That’s what I’d say about India today. When you think about it more widely – America had Iraq; also Americans don’t necessarily quickly vote for healthcare (even those without health insurance don’t seem to see the merit of it) – there are all kinds of ways in which democratic debate doesn’t proceed well. And I’m really amazed that there is so little discontent in this country about the intellectually inadequate idea of “austerity”. It can’t be a tribute to democracy in Britain that Labour leaders should be tempted to endorse austerity just as most of the best economists in the world have rejected it. That the Labour Party thinks that by embracing the “wisdom” of austerity it can capture votes is not a tribute to the functioning and practice of democracy in the United Kingdom. That should not be the case. So all democracies have limitations. But the limitation in India is much more detrimental to the good life of the people than even the eccentricity of the opposition party backing austerity today. And that’s bloody eccentric!

JD: There’s another aspect of your views about democracy and democratic participation that intrigues me. There are moments where you come close to holding that democratic participation itself is part of what it is to live a flourishing human life – that’s an almost neo-Roman or republican view. Is that your view?

AS: I regard the advocates of that kind of view to be saying something important – namely that participation is important in our lives. But it can’t be the only thing that we value. You cannot say that if I lived in an authoritarian system, that had happened to generate for me a better level of education, healthcare and immunisation, that that isn’t an achievement because it wasn’t achieved through republican methods, I won’t accept that! You’ve achieved something. It would have been better if it had better had it been achieved through neo-Roman self-government, but it is better to have achieved it than not at all.

JD: And this is an insight that is derived from the example of the Asian economies that we discussed earlier, because one of the things they show is that having a market economy doesn’t entail having a particular set of political institutions. Market economies, in other words, flourish in a variety of institutional contexts.

AS: Yes, but it would difficult to think of any successful market economy in which the state doesn’t play an important part. And that was a point that was made already by Adam Smith in 1776! It’s true of Germany, of the United States, it’s true of Britain when it was doing very well, it’s true of Japan, China, Korea, Taiwan and so on. So I think, there could be variations, but a certain there is a certain necessity for the state to play its part, along with people having the freedom to pursue market opportunities.

JD: I was thinking more of the fact that Singapore and Korea in the 1980s were authoritarian market states, in which individuals had the freedom to pursue market opportunities but political freedoms were curtailed. So civil society flourished alongside authoritarian political institutions.

AS: I think that’s right. Historically, democracy was a big change that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries in the West. But there had been degrees of democratic participation in authoritarian states. The point was made very clearly in the 7th century AD by Shotoku, the prince of Japan. He said that in order to have good governance we have to talk and consult with people. This was 600 years before Magna Carta. In some ways there has to be consultation. Magna Carta was just about that – it wasn’t about making Britain a democratic state. But it was a contribution to that Millian perspective according to which democracy is government by discussion. Look at China. I happen to be closely associated with two Chinese universities, Peking University and the People’s University. On the subject of healthcare, which interested a number of economists in Peking University, these economists were not being listened to. But eventually the Chinese government saw fit to hear their technical arguments, including about inequality, that they had to rein in inequality. So the point is this: would I prefer have the Chinese form of government rather than the Indian? No I wouldn’t. On the other hand, would I say that it’s authoritarian in the sense that it’s like Genghis Khan deciding what he wants to do? No. It isn’t like that.

JD: I find this fascinating. For it seems to me that our vocabulary is rather impoverished when it comes to trying to describe what it is, exactly, that the Chinese have. We reach for a shorthand such as “authoritarian market state” which, if you’re right, doesn’t come close to capturing the reality of things there.

AS: The point is that China is successful. And that success is based on enlightenment. Listen, democracy or government by discussion is a very important contribution to enlightenment. But enlightened decisions make a contribution even if they don’t happen to have been arrived at through democratic means. I irritated some people when I said once that I believe Keynes had the right things to say on austerity but that, on the other hand, he does not sufficiently defend the role of the state – namely that it has to do things like healthcare, social services and the basic welfare state. And I irritated some of my friends when I said that on this subject, Keynes had less to say than Bismarck did. Now Bismarck was not a democrat, but he was enlightened on this subject. I don’t see anything puzzling about China. Can I give an example of their making a mistake? Of course. I can mention famine. I can mention their abandonment of universal healthcare in 1979. That was a huge mistake.

So it’s fragile, but right now they’re in terrific shape and we have a lot to learn – about what they’re doing rather than the undemocratic procedures that lie behind it. I think we should be able to distinguish between why a policy is right and whether it was arrived at by the right procedure. My hope is that because the intellectuals in China are quite strong and because the commitment to government by discussion (this is actually a term of Bagehot’s) is very strong, it won’t be easy for the Communist Party to change things, even if they wanted to. So I’m completely at peace. I don’t see any contradiction there. I don’t see that I have anything to explain. It’s not as if I’ve said that China has an authoritarian system and they’ve never had any problems. I didn’t. Democracy is not the only thing we should be looking at. After all, the Soviet record in education was extraordinarily good. Look at those bits of Asia today that were part of the Soviet Union. They have enormously better levels of education than the neighbouring states. The Soviets did know something. And in this case communist ideology and Marxism made a major contribution. It had nothing to do with democracy.

Yasuni national park. Murray Cooper/Minden Pictures/Corbis

Yasuni national park. Murray Cooper/Minden Pictures/Corbis