Faith remains a potent presence at the highest level of UK politics despite a growing proportion of the country’s population defining themselves as non-religious, according to the author of a new book examining the faith of prominent politicians.

Nick Spencer, research director of the Theos thinktank and the lead author of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, uses the example that all but one of Britain’s six prime ministers in the past four decades have been practising Christians to make his point.

The book examines the faith of 24 prominent politicians, mostly in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. “The presence and prevalence of Christian leaders, not least in some of the world’s most secular, plural and ‘modern’ countries, remains noteworthy. The idea that ‘secularisation’ would purge politics of religious commitment is surely misguided,” it concludes.

It includes “theo-political biographies” of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar’s daughter who has spoken publicly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her predecessors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Only John Major is absent from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer writes that May is a “politician with strong views rather than a strong ideology, and those views were seemingly shaped by her Christian upbringing and faith. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, ‘a moral backing to what I do, and I would hope that the decisions I take are taken on the basis of my faith’.”

May told Desert Island Discs in 2014 that Christianity had helped to frame her thinking but it was “right that we don’t flaunt these things here in British politics”. According to Spencer, “in this regard at very least, May practises what she preaches”.

However, the prime minister’s apparent reticence did not stop her lambasting Cadbury’s and the National Trust this month over their supposed downgrading of the word Easter in promotional materials and packaging.

Elsewhere, the book looks at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European leaders, three Australian prime ministers and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five leaders from other countries – including Nelson Mandela – complete the list.

The “great secular hope” was that religion would fade out of the political landscape, Spencer writes. But “the last 40 years have turned out somewhat different”, with the emergence of political Islam, the strength of Catholicism in central and south America and the explosion of Pentecostalism in the global south.

Even in the west, “Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so,” he says.

But Spencer told the Guardian: “There is no one size fits all, politically. You don’t find them clustering on the political spectrum.”

At the rightwing end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the president of Paraguay between 2008 and 2012, a prominent Catholic “bishop of the poor”, liberation theologist and part of a wave of leftwing leaders in Latin America.

There were also significant differences in the political contexts in which Christian politicians were operating, Spencer said. “There are places where you stand to make a lot of political capital by talking about your faith – such as the US or Russia.

“But in countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-sceptical, politicians stand to lose political capital. No politician in the UK or France talks about their faith in order to win over the electorate.”

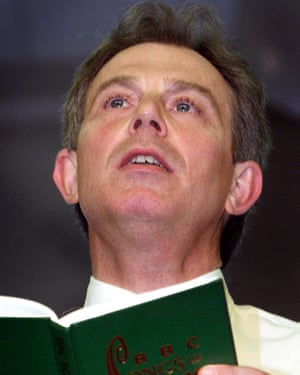

Tony Blair in 2001. Photograph: Jonathan Evans/Reuters

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

After he left Downing Street, Blair spoke of the difficulties of talking about “religious faith in our political system. If you are in the American political system or others then you can talk about religious faith and people say ‘yes, that’s fair enough’ and it is something they respond to quite naturally. You talk about it in our system and, frankly, people do think you’re a nutter.”

Although Blair’s faith reportedly shaped all his key policy decisions in office, the same was not true of all politicians, said Spencer. “There are some politicians for whom faith has shaped politics, and others for whom you can be more confident that politics are shaping faith. Trump is an example of that,” he said.

According to the chapter on Trump – a late addition to the book – the president “is not known for his interest in theology, the church or religion. His statements about faith, not least his own faith, have been infrequent and vague. And yet, Trump is insistent that he believes in God, loves the Bible and has a good relationship with the church … Simply to dismiss Trump’s faith talk would be to dismiss Trump, and 2016 showed that that is a mistake”.

Leaders’ faith

Theresa May Daughter of an Anglican vicar, the British prime minister goes to church most Sundays and has said her Christian faith is “part of who I am and therefore how I approach things ... [it] helps to frame my thinking and my approach”.

Vladimir Putin The Russian president has increasingly presented himself as a man of serious personal faith, which some suggest is connected to a nationalist agenda. He reportedly prays daily in a small Orthodox chapel next to the presidential office.

Angela Merkel The German chancellor is a serious Christian believer but one whose faith is very private. “I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life,” she told an interviewer in 2012.

Fernando Lugo The former president of Paraguay was also a prominent Catholic bishop, a champion of the poor and a leading advocate of liberation theology. He urged “defending the gospel values of truth against so many lies, justice against so much injustice, and peace against so much violence”.

Viktor Orbán A relatively recent convert to faith, the Hungarian prime minister frequently invokes the need to defend “Christian Europe” against Muslim migrants. “Christianity is not only a religion, but is also a culture on which we have built a whole civilisation,” he said in 2014.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf The president of Liberia and a Nobel peace laureate, Sirleaf was brought up in a devout family and has frequently appealed for “God’s help and guidance” during her 10 years as head of state. In a 2010 speech, she described religion and spirituality as “the cornerstone of hope, faith and love for all peoples and races”.