Children with a stable home life do better at school. Focus less on catchment areas and more on relationship counselling

'The more stable a home life children have, the better they will be able to concentrate at school, and the better grades they will have.' Photograph: Eye Ubiquitous / Alamy/Alamy

Parents do anything they can to give their kids the best chance to succeed. According to a report published by the Sutton Trust, a third of "professional parents" with children aged between five and 16 have moved to an area because they think it has good schools, and 18% to a specific school's catchment area.

Some go further: 6% of the 1,000 parents surveyed admitted attending church services when they hadn't previously to help their children get a place at a church school; 3% admitted using a relative's address to get children into a particular school; and 2% said they had bought a second home and used that address to qualify for a place.

As well as a fair few white lies, it all adds up to a colossal amount of money spent on trying to improve your children's chances of doing better educationally – and the point the Sutton Trust wants to make is that the more money you have, the more you can do to "buy" an advantage. Its recommendation – that the government should step in and encourage ballots for school places, to make selection fairer – seems a good one. After all, the drive to make things as rosy as possible for your offspring is inherent in all us parents: it's what we're designed to do, to achieve the best possible life chances for our children. That doesn't, or shouldn't, amount to fraud – it's a braver person than me who would cast the first stone and condemn parents for trying to give their kids the best start.

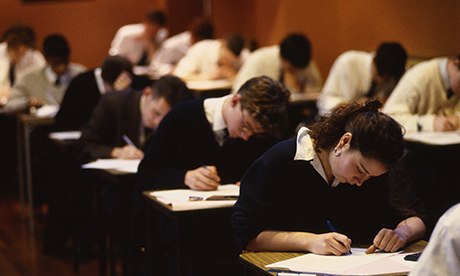

So it seems strange that parents, while focusing so intently on school, seem often to ignore a much cheaper way of improving their children's educational lot. Because the more stable a home life children have, the better they will be able to concentrate at school, the better behaved they will be in school, and the better grades they will have on leaving school.

There's plenty of research to back all this up: a recent study by the Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre found that children aged seven and older tended to do more poorly in exams and to behave badly at school if their parents split up. Another report funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, released at the end of last year, found that a stable family life meant children were more likely to take in what's being offered in the classroom. According to the Royal College of Psychiatrists, teenagers whose parents are fighting or separating may find it difficult to concentrate at school.

Of course, many marriages are completely on track, 100% hunky dory, and here the only thing worth stressing about is a school's Sats and GCSE results. But it may not be you, and I have to admit it's not me either: I've been married for more than a quarter of a century, and the one thing I'm sure of is that it's not a bed of roses. I've also got four children aged between 11 and 21; and while I'm truly grateful to the many teachers who have taught them, and the schools they've been pupils at, I've become more convinced as the years go by that a stable home is an absolutely vital ingredient in how they're getting on – and certainly much more crucial than where their school sits in the local league table.

So shelling out a few hundred quid for a course of Relate counselling sessions (and if you're on a low income, it can be a lot less, or even free) could be a much better use of the family's funds than spending thousands on moving house. Sure, your children might end up at a school whose exam results aren't quite so glowing – but that's more than offset by the fact that they are likely to do better for having happier parents (and moving house, after all, puts even more pressure on a relationship).

According to Relate, 80% of clients who went for adult relationship counselling said their partnership had been strengthened as a result. According to a whole pile of research stretching back across many decades, children tend to do best when they're raised in a stable family. I can't help wondering whether the only sure winners from the scramble to live by the best school gates are estate agents rather than the very children the move is designed to help.