|

| Rob Moody: a Melbournian with a famous interest in sport but also a "massive footy hater" © Rob Moody |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

|

At the start I'll assume that the reason you are reading this is that you're a cricket fan and you have an internet connection. Therefore it's also not a stretch to assume that if you don't know a man named Rob Moody by his full name, you probably know him by his Youtube moniker, Robelinda2.

I couldn't name every member of the ICC board from memory but I know who Rob Moody is, and among cricket fans that puts me in the majority. Moody is a kind of cricket historian, an archivist, a DIY publisher, a superfan and a superfreak. By any measurement he's one of the unsung heroes of the game.

The Melbourne-based cricket lover draws upon thousands and thousands of hours of lovingly recorded cricket footage to edit and publish Youtube clips of fantastic and forgotten moments of cricket history; thousands of videos with millions of views.

Certain reoccurring themes tend to permeate the Moody oeuvre and give a small indication of his likes and dislikes as a connoisseur of the game. His obsession with Inzamam-ul-Haq's travails has resulted in works like "72 funniest Inzamam Ul Haq LBW's" and "23 funniest Inzamam run outs". One of his most-watched clips, 2,096,051 views and counting, is of a viciously rearing David Saker bouncer to the head of South Australia's Jeff Vaughan on a lively Bellerive wicket. That moment was broadcast on a long forgotten Australian cable channel and didn't even rate a mention in Wisden, typifying the type of fascinating marginalia that makes Moody's channel so enticing to cricket's millions of trainspotters.

There are no geographical borders in Moody's search for cricket videos, with one fan taking to the comments section to leave an apt compliment: "if cricket was played on Mars, I bet this guy would have videos from there too."

For those who love and write about the game, Moody's archive has become a portable library, and the exhaustive amount of game footage is augmented by a number of fascinating old documentaries that would be lost to most of us without Moody's guiding hand.

On the morning of the Adelaide Test I discussed Moody's remarkable hobby with him and got an insight into the love for the game that drives his efforts. He says he has footage of virtually every game played in Australia for the last 30 years. They've been transferred onto CDs that are stored in around 25 folders in his Melbourne home. Each folder contains 1000 discs, and together they make up a near-complete archive of Australian cricket in his lifetime.

The earliest home-recorded VHS that Moody still has is footage from the 1982-83 season. "It was recorded after my dad recorded a John Wayne movie. The highlights came on after," he says. "I managed to keep the video." Plenty of similar discoveries have come from unlabelled VHS tapes he bought in bulk lots at garage sales and on eBay.

Sometime around the mid-1980s, Moody's hobby escalated and by his late teens he was recording every ball of every game that his video-buying budget could cover. In a detail that would be familiar to any child of the '80s, he recalls often hitting the pause button between overs to avoid wasting tape on the commercials; the problem was he'd often forget to resume recording and would miss a couple of overs. The other hazard was the threat of unlabelled tapes being wiped to make way for episodes of Punky Brewster, which his sister would record.

Moody's cricket video archive has been both helped and hindered by the emergence of decidedly more sophisticated recording technologies than were available when his hobby started. His first digital recorder, purchased in 2004, cost A$4000 (approximately US$3600). It only had a 10GB hard drive, and at that point the cost of blank discs to transfer his recordings to was prohibitively expensive (up to $10 each).

"Then the problem came that they were too cheap and they were rubbish, "he says. Fortunately he was in the habit of backing up his digital conversions, as hundreds of the newer, cheaper discs proved to be of such poor quality they didn't last even a decade. Ironically enough, the VHS tapes he stopped using in early 2004 have proven indestructible and still play at the same quality even 30 years after the initial recording. By contrast he says he throws out 500 DVDs per year that have simply stopped working. "It's a massive effort to keep everything from just fading away, because the technology is unreliable. Even with hard drives they just die, he laments."

Moody played club cricket as an opening batsman for five years in the '90s before finger injuries started to endanger his burgeoning career gigging in various bands around Melbourne. Now he teaches guitar.

So far his biggest hurdle in maintaining his Youtube channel has not been the stiff arm of authority but moderating long and unwieldy comment threads that veer into bizarre and legally problematic tangents. "Every day there is close to a thousand comments to go through. Heaps of them are abuse and threats," he says. He's remarkably calm about this imposition, which he calls "par for the course".

"In that first year it definitely was pretty insane. I actually couldn't believe the absolute torrent of abuse and pretty crazy threats." He received abusive messages by email and phone, and to his horror, one unhappy viewer even showed up at his work to issue a threat. "He can't have been much over 18 and he ended up happy to speak to me. That was kind of weird," Moody says with remarkably good humour.

Contrary to my own impressions, he says the worst of the threats came not from Indian fans of Sachin Tendulkar, who Moody often jokes over and ribs, but his own countrymen. "Initially there were a lot of angry Aussies, believe it or not."

| | | | |

| |

| Moody has footage of virtually every game played in Australia for the last 30 years. They've been transferred onto CDs that are stored in around 25 folders in his home. Each folder contains 1000 discs |

| |

| | |

|

That the Robelinda2 channel still exists is down to caution, and good luck. Moody says the key to its survival is tending towards older material when making new uploads. He has a precise and nuanced understanding of the various rights holders of more recent footage, and is keenly aware of what he is and isn't likely to get away with.

Youtube's copyright detection system is automated, so Moody's reputation amongst fans would count for nothing if he transgressed. The threat of three strikes and the complete termination of his channel remains, and such an eventuality would take with it his entire archive of material. Friends of Moody's have not been as lucky, and he says thousands of videos that didn't breach any of the site's regulations have been lost as collateral damage.

"When it goes I'm certainly not going to put it up again, because it would be way too much work to do it all over again," he says with a shrug of resignation. Moody is pragmatic about the right of cricket boards and broadcasters to enforce copyright regulations and focuses more of his energies on the content he can provide to fellow fans.

Right now his children are too young to understand their dad's remarkable hobby, but when he mentions that his wife had "always known" about the obsession, he says it with a hearty laugh, as if it could be construed as a dark secret to some.

When asked about his flair for editing compilation videos, it's surprising to learn that most of them were made long before he converted to digital formats. At a young age he took note of the way Channel Nine's highlight packages were edited and used his own homespun production techniques to create similar reels for himself. Much of what Moody has uploaded was created not on modern digital editing software, but through a laborious manual process, using two VCRs. It also pays to bear in mind that he never foresaw a time or technology that would allow for the end product to be viewed on any screen other than the one in his own living room.

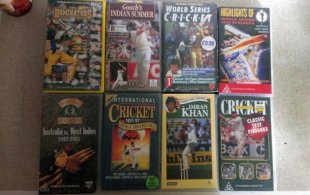

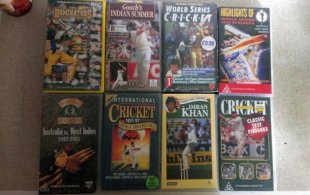

Moody says these self-created highlights packages include every half-century and century televised in Australia in the time he has been recording games. He estimates that he owns every commercially produced VHS cricket video ever released in England and Australia, including obscure subscription-only titles like Cover Point, which were advertised in cricket magazines in the '80s and '90s. The latter cost around $100 per video, an almost laughable sum in hindsight, but many yielded gems he never would have seen otherwise.

Moody says some of those titles now sell in online auctions for four-figure sums. For instance, not even Cricket South Africa has copies of a collection of rare videos he has from the South African rebel tours, which remain a lost world of cricket history. He says that copies have sold on eBay for up to $4000, and he has even fielded requests from players who featured in the games to provide them with footage from the tours. Want to see Sylvester Clarke hit Peter Kirsten with a bouncer in 1983-84? Thanks to Moody, you now can.

|

| Moody says he throws out 500 DVDs per year that have simply stopped working © Rob Moody |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

Moody still talks with a boyish enthusiasm of the days when rain delays in Australian internationals saw Channel Nine delve into its archives to show some old gold. He bemoans the current trend in which Nine will "return to normal programming, which of course means an Elvis movie we've all seen a million times. I don't understand how that is normal programming."

Moody's views on the game are trenchant and often surprising. His decision to record the ever-expanding schedule of T20 games in a lower-quality format than he uses for Tests and one-day cricket is as much a philosophical one as to do with practicalities. He says the newest format is "mildly entertaining when it's on but there's obviously a different vibe about it… I certainly don't dislike it to any great extent but it's clearly an inferior type of cricket."

Unusually for a Melbournian with such a famous interest in sport, Moody calls himself a "massive footy hater" and takes no interest in any other sport ("and thank god, because I don't have any time"). His early interest in cricket was kindled by the sight of Australia's mid-'80s one-day international clashes against West Indies. The passion in his voice is clear when he enters any discussion about West Indies cricket, and he retains a deep knowledge of their golden era.

There are few gaps in his collection other than some games from Australia's 1994 tour of South Africa, but he is always on the look-out for overseas tour footage from before the advent of Australian cable TV in the mid-1990s. He also makes the valid point that between the 1991 and 1999 Indian tours of Australia, the only ways for fans like him to fully appreciate the talents of Sachin Tendulkar was through those early wonder years of Australian cable TV.

Moody is philosophically opposed to claiming advertising revenue from his videos, adding that he dislikes watching advertisements on videos uploaded by other users, and so would feel hypocritical putting them on his own. "It just seems really dodgy," he says. "It would also be extra hassles with legal matters."

With the sheer volume of video footage in his collection, Moody doesn't have a lot of room for cricket books but says he owns a hundred or so. He narrows his focus on historical tomes and particularly enjoys the work of Christian Ryan, Gideon Haigh ("clearly the best"), Mike Atherton and Mike Coward. He laughs heartily recalling an incident where he sat in a Melbourne cinema watching Max Walker deal admirably with heckling from a series of fellow patrons on account of the former Australian fast bowler's literary output.

One room of Moody's house dedicated to both music and his cricket DVDs, and - this would be familiar to collectors everywhere - the overflow ends up in "the other room". Soon enough his children will outgrow their shared bedroom and claim the space.

For fans like me, Moody's videos have filled the gaps on half-remembered events and resulted in remarkable journeys down digital rabbit holes, sometimes for hours on end. They are full of greatness, happiness, badness and madness, and his enthusiasm for the game is infectious. I don't doubt that his willingness to share his collection has encouraged others to adopt some of his passion and selflessness and upload their own forgotten gems. For that we should all be thankful.

Brushing aside the suggestion that he is a kind of folk hero in the world of cricket, Moody says, "It's just a Youtube channel. It's one amongst millions. I don't think it's as big a deal as people think."

On that point alone, he couldn't be more wrong.