The Tiger and the Fox

Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history

Ashley Mallett

May 8, 2013

A

| |||

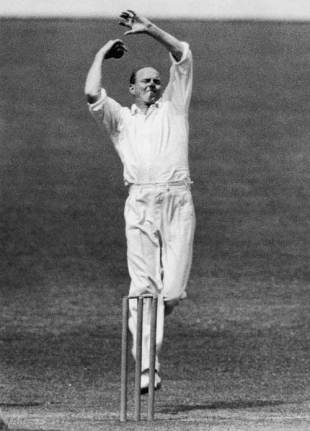

Between the world wars, Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett reigned supreme. They were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history. O'Reilly, the Tiger, and Grimmett, the Fox, were both legspinners but they approached their art as differently as Victor Trumper and Don Bradman approached batting.

Arms and legs flailing in the breeze, O'Reilly stormed up to the crease with steam coming out of his ears. He believed in all-out aggression, and called himself a "boots'n'all" competitor. Bradman, who reckoned O'Reilly to have been the best bowler he saw or played against, said he had the ability to bowl a legbreak of near medium pace that consistently pitched around leg stump and turned to nick the outside edge or the top of off.

"Bill also bowled a magnificent bosey which was hard to pick, and which he aimed at middle and leg stumps," said Bradman in a letter he wrote to me in 1989. "It was fractionally slower than his legbreak and usually dropped a little in flight and 'sat up' to entice a catch to one of his two short-leg fieldsmen. These two deliveries, combined with great accuracy and unrelenting hostility, were enough to test the greatest of batsmen, particularly as his legbreak was bowled at medium pace - quicker than the normal run of slow bowlers - making it extremely difficult for a batsman to use his feet as a counter measure. Bill will always remain, in my book, the greatest of all."

O'Reilly first came up against Bradman in the summer of the 1925-26 season, when Tiger's Wingello took on the might of Bradman's Bowral. Sixteen-year-old Bradman, who to his 19-year-old adversary was hardly any bigger than the outsized pads he wore, edged a high-bouncing legbreak straight to first slip when on 32. But the Wingello captain, Gallipoli hero Selby Jeffrey, was busy lighting his pipe, and the chance went begging.

Stumps were drawn with Bradman 232 not out, leaving the Tiger snarling in disbelief and raising his eyes to the heavens at the blatant injustice of it all. The game resumed the next Saturday afternoon. Bradman faced the first ball from the wounded Tiger. It pitched leg and took the top of off.

In the year O'Reilly came into this world, 1905, Grimmett tore a hole in his new blue suit, clambering over the barbed wire at Wellington's Basin Reserve to watch Trumper hit a famous hundred. In 1914, Grimmett sailed into Sydney from his native New Zealand, seeking cricketing fame. But it wasn't until a long stint in Sydney and more fruitless years in Melbourne before a last throw of the dice in Adelaide proved to be a haven for an unwanted bowler.

Grimmett began his Test career against England at the SCG in 1925, taking a match haul of 11 for 82. He starred in Australian tours of England in 1926 and 1930, but it was in the Adelaide Test of 1932, O'Reilly's debut, that the Tiger and the Fox first joined forces. Grimmett was the master and O'Reilly the apprentice, in a game that was a triumph for Bradman (299 not out) and Grimmett (14 for 199).

| It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne | |||

O'Reilly was amazed by the way Grimmett bowled: "I learned a great deal watching Grum [the nickname Bill always used for his spinning mate] wheel away. I watched him like a hawk. He was completely in control. His subtle change of pace impressed me greatly."

The pair played two Tests that series and two more in the Bodyline series of 1932-33, before O'Reilly took over as Australia's leading spinner when Grimmett was dropped. They were back in harness for the 1934 Ashes - the Tiger's first England tour, Grimmett's third. Here's O'Reilly on their unforgettable partnership:

"It was on that tour that we had all the verbal bouquets in the cricket world thrown at us as one of the greatest spin combinations Test cricket had seen. Bowling tightly and keeping the batsmen unremittingly on the defensive, we collected 53 [Grimmett 25, O'Reilly 28] of the 73 English wickets that fell that summer. Each of us collected more than 100 wickets on tour and it would have needed a brave, or demented, Australian at that time to suggest that Grimmett's career was almost ended."With Grum at the other end I knew full well that no batsman would be allowed the slightest respite. We were fortunate in that our styles supplemented each other. Grum loved to bowl into the wind, which gave him an opportunity to use wind-resistance as an important adjunct to his schemes regarding direction. He had no illusions about the ball 'dropping', as we hear so often these days, before its arrival at the batsman's proposed point of contact. To him that was balderdash. In fact, he always loved to hear people making up verbal explanations for the suspected trickery that had brought a batsman's downfall. If a batsman had thought the ball had dropped, all well and good. Grimmett himself knew that it was simply change of pace that had made the batsman think that such an impossibility had happened."

| |||

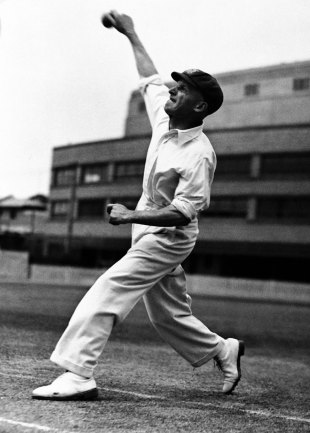

While O'Reilly was all-out aggression, Grimmett was steady and patient. They both possessed a stock ball that turned from leg. O'Reilly's deliveries came at pace: his legbreak spat like a striking cobra, and his wrong'un reared at the chest of the batsman. For any batsman in combat with the Tiger there was no respite, no place to hide.

In contrast, Grimmett wheeled away in silence. He was like the wicked spider, spinning a web of doom. Sometimes it took longer for him to snare his victim, but despite their vastly different styles and methods of attack they were both deadly. A batsman caught at cover off Grimmett was just as out as a man who lost his off stump to a ball that pitched leg and hit the top of off from O'Reilly.

Bradman once wrote me: "I always classified Clarrie Grimmett as the best of the genuine slow legspinners, (I exclude Bill O'Reilly because, as you say, he was not really a slow leggie) and what made him the best, in my opinion, was his accuracy. Arthur Mailey spun the ball more - so did Fleetwood-Smith and both of them bowled a better wrong'un but they also bowled many loose balls. I think Mailey's bosey was the hardest of all to pick.

"Clarrie's wrong'un was in fact easy to see. He telegraphed it and he bowled very few of them. His stock-in-trade was the legspinner with just enough turn on it, plus a really good topspin delivery and a good flipper (which he cultivated late in life). I saw Clarrie in one match take the ball after some light rain when the ball was greasy and hard to hold, yet he reeled off five maidens without a loose ball. His control was remarkable."

Grimmett invented the flipper, which Shane Warne, at the height of his brilliant career, bowled so well. Like Grimmett, Warne didn't have a great wrong'un, but he possessed a terrific stock legbreak and a stunning topspinner. When O'Reilly asked SF Barnes where he placed his short leg for the wrong'un, Barnes replied: "Never bowled the bosey… didn't need one."

Imagine if Grimmett and O'Reilly had played 145 Tests, the same number as Warne. At the rate they took their wickets, Grimmett would have snared a shade under 870 and O'Reilly 770. In reality Grimmett played just 37 Tests and O'Reilly 27, but what an impact they had on cricket. It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne.

The Tiger and the Fox were unique in their contrasting styles, but they had one thing in common: they were spin-bowling predators. Their prey was any batsman who ventured to the crease when they were on the hunt.