'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 26 March 2019

Monday, 25 March 2019

How the media let malicious idiots take over

Be it Jacob Rees-Mogg or Nigel Farage, blusterers and braggarts are rewarded with platforms that distort our political debate writes George Monbiot in The Guardian

Jacob Rees-Mogg during his LBC radio phone-in programme, April 2018. Photograph: Ian West/PA

If our politics is becoming less rational, crueller and more divisive, this rule of public life is partly to blame: the more disgracefully you behave, the bigger the platform the media will give you. If you are caught lying, cheating, boasting or behaving like an idiot, you’ll be flooded with invitations to appear on current affairs programmes. If you play straight, don’t expect the phone to ring.

In an age of 24-hour news, declining ratings and intense competition, the commodity in greatest demand is noise. Never mind the content, never mind the facts: all that now counts is impact. A loudmouthed buffoon, already the object of public outrage, is a far more bankable asset than someone who knows what they’re talking about. So the biggest platforms are populated by blusterers and braggarts. The media is the mirror in which we see ourselves. With every glance, our self-image subtly changes.

When the BBC launched its new Scotland channel recently, someone had the bright idea of asking Mark Meechan – who calls himself Count Dankula – to appear on two of its discussion programmes. His sole claim to fame is being fined for circulating a video showing how he had trained his girlfriend’s dog to raise its paw in a Nazi salute when he shouted: “Sieg heil!” and “Gas the Jews”. The episodes had to be ditched after a storm of complaints. This could be seen as an embarrassment for the BBC. Or it could be seen as a triumph, as the channel attracted massive publicity a few days after its launch.

The best thing to have happened to the career of William Sitwell, the then-editor of Waitrose magazine, was the scandal he caused when he sent a highly unprofessional, juvenile email to a freelance journalist, Selene Nelson, who was pitching an article on vegan food. “How about a series on killing vegans, one by one. Ways to trap them? How to interrogate them properly? Expose their hypocrisy? Force-feed them meat,” he asked her. He was obliged to resign. As a result of the furore, he was snapped up by the Telegraph as its new food critic, with a front-page launch and expensive publicity shoot.

Last June, the scandal merchant Isabel Oakeshott was exposed for withholding a cache of emails detailing Leave.EU co-founder Arron Banks’ multiple meetings with Russian officials, which might have been of interest to the Electoral Commission’s investigation into the financing of the Brexit campaign. During the following days she was invited on to Question Timeand other outlets, platforms she used to extol the virtues of Brexit. By contrast, the journalist who exposed her, Carole Cadwalladr, has been largely frozen out by the BBC.

This is not the first time Oakeshott appears to have been rewarded for questionable behaviour. Following the outrage caused by her unevidenced (and almost certainly untrue) story that David Cameron put his penis in a dead pig’s mouth, Paul Dacre, the then editor of the Daily Mail, promoted her to political editor-at-large.

The Conservative MP Mark Francois became hot media property the moment he made a complete ass of himself on BBC News. He ripped up a letter from the German-born head of Airbus that warned about the consequences of Brexit, while announcing: “My father, Reginald Francois, was a D-Day veteran. He never submitted to bullying by any German, and neither will his son.” Now he’s all over the BBC.

In the US, the phenomenon is more advanced. G Gordon Liddy served 51 months in prison as a result of his role in the Watergate conspiracy, organising the burglary of the Democratic National committee headquarters. When he was released, he used his notoriety to launch a lucrative career. He became the host of a radio show syndicated to 160 stations, and a regular guest on current affairs programmes. Oliver North, who came to public attention for his leading role in the Iran-Contra scandal, also landed a syndicated radio programme, as well as a newspaper column, and was employed by Fox as a television show host and regular commentator. Similarly, Darren Grimes, in the UK, is widely known only for the £20,000 fine he received for his activities during the Brexit campaign. Now he’s being used by Sky as a pundit.

The most revolting bigots, such as Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump, built their public profiles on the media platforms they were given by attacking women, people of colour and vulnerable minorities. Trump leveraged his notoriety all the way to the White House. Boris Johnson is taking the same track, using carefully calibrated outrage to keep himself in the public eye.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the unscrupulous, duplicitous and preposterous are brought to the fore, as programme-makers seek to generate noise. Malicious clowns are invited to discuss issues of the utmost complexity. Ludicrous twerps are sought out and lionised. The BBC used its current affairs programmes to turn Nigel Farage and Jacob Rees-Mogg into reality TV stars, and now they have the nation in their hands.

My hope is that eventually the tide will turn. People will become so sick of the charlatans and exhibitionists who crowd the airwaves that the BBC and other media will be forced to reconsider. But while we wait for a resurgence of sense in public life, the buffoons who have become the voices of the nation drive us towards a no-deal Brexit and a host of other disasters.

If our politics is becoming less rational, crueller and more divisive, this rule of public life is partly to blame: the more disgracefully you behave, the bigger the platform the media will give you. If you are caught lying, cheating, boasting or behaving like an idiot, you’ll be flooded with invitations to appear on current affairs programmes. If you play straight, don’t expect the phone to ring.

In an age of 24-hour news, declining ratings and intense competition, the commodity in greatest demand is noise. Never mind the content, never mind the facts: all that now counts is impact. A loudmouthed buffoon, already the object of public outrage, is a far more bankable asset than someone who knows what they’re talking about. So the biggest platforms are populated by blusterers and braggarts. The media is the mirror in which we see ourselves. With every glance, our self-image subtly changes.

When the BBC launched its new Scotland channel recently, someone had the bright idea of asking Mark Meechan – who calls himself Count Dankula – to appear on two of its discussion programmes. His sole claim to fame is being fined for circulating a video showing how he had trained his girlfriend’s dog to raise its paw in a Nazi salute when he shouted: “Sieg heil!” and “Gas the Jews”. The episodes had to be ditched after a storm of complaints. This could be seen as an embarrassment for the BBC. Or it could be seen as a triumph, as the channel attracted massive publicity a few days after its launch.

The best thing to have happened to the career of William Sitwell, the then-editor of Waitrose magazine, was the scandal he caused when he sent a highly unprofessional, juvenile email to a freelance journalist, Selene Nelson, who was pitching an article on vegan food. “How about a series on killing vegans, one by one. Ways to trap them? How to interrogate them properly? Expose their hypocrisy? Force-feed them meat,” he asked her. He was obliged to resign. As a result of the furore, he was snapped up by the Telegraph as its new food critic, with a front-page launch and expensive publicity shoot.

Last June, the scandal merchant Isabel Oakeshott was exposed for withholding a cache of emails detailing Leave.EU co-founder Arron Banks’ multiple meetings with Russian officials, which might have been of interest to the Electoral Commission’s investigation into the financing of the Brexit campaign. During the following days she was invited on to Question Timeand other outlets, platforms she used to extol the virtues of Brexit. By contrast, the journalist who exposed her, Carole Cadwalladr, has been largely frozen out by the BBC.

This is not the first time Oakeshott appears to have been rewarded for questionable behaviour. Following the outrage caused by her unevidenced (and almost certainly untrue) story that David Cameron put his penis in a dead pig’s mouth, Paul Dacre, the then editor of the Daily Mail, promoted her to political editor-at-large.

The Conservative MP Mark Francois became hot media property the moment he made a complete ass of himself on BBC News. He ripped up a letter from the German-born head of Airbus that warned about the consequences of Brexit, while announcing: “My father, Reginald Francois, was a D-Day veteran. He never submitted to bullying by any German, and neither will his son.” Now he’s all over the BBC.

In the US, the phenomenon is more advanced. G Gordon Liddy served 51 months in prison as a result of his role in the Watergate conspiracy, organising the burglary of the Democratic National committee headquarters. When he was released, he used his notoriety to launch a lucrative career. He became the host of a radio show syndicated to 160 stations, and a regular guest on current affairs programmes. Oliver North, who came to public attention for his leading role in the Iran-Contra scandal, also landed a syndicated radio programme, as well as a newspaper column, and was employed by Fox as a television show host and regular commentator. Similarly, Darren Grimes, in the UK, is widely known only for the £20,000 fine he received for his activities during the Brexit campaign. Now he’s being used by Sky as a pundit.

The most revolting bigots, such as Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump, built their public profiles on the media platforms they were given by attacking women, people of colour and vulnerable minorities. Trump leveraged his notoriety all the way to the White House. Boris Johnson is taking the same track, using carefully calibrated outrage to keep himself in the public eye.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the unscrupulous, duplicitous and preposterous are brought to the fore, as programme-makers seek to generate noise. Malicious clowns are invited to discuss issues of the utmost complexity. Ludicrous twerps are sought out and lionised. The BBC used its current affairs programmes to turn Nigel Farage and Jacob Rees-Mogg into reality TV stars, and now they have the nation in their hands.

My hope is that eventually the tide will turn. People will become so sick of the charlatans and exhibitionists who crowd the airwaves that the BBC and other media will be forced to reconsider. But while we wait for a resurgence of sense in public life, the buffoons who have become the voices of the nation drive us towards a no-deal Brexit and a host of other disasters.

Thursday, 21 March 2019

Wednesday, 20 March 2019

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Employment Tribunal decision.

Published 19 March 2019

- Decision date:

- 8 March 2019

- Country:

- England and Wales

- Jurisdiction code:

- Age Discrimination, Race Discrimination

Read the full decision in Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018 - Withdrawal.

Published 19 March 2019

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

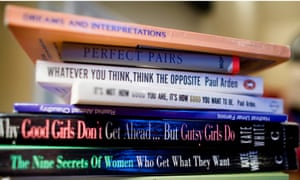

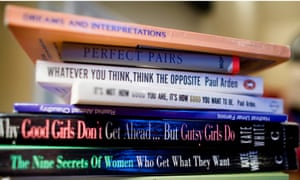

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)