'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 21 March 2019

Wednesday, 20 March 2019

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Employment Tribunal decision.

Published 19 March 2019

- Decision date:

- 8 March 2019

- Country:

- England and Wales

- Jurisdiction code:

- Age Discrimination, Race Discrimination

Read the full decision in Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018 - Withdrawal.

Published 19 March 2019

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

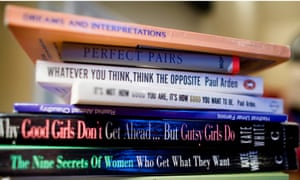

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Sunday, 17 March 2019

Why we should be honest about failure

Disappointment is the natural order of life. Most people achieve less than they would like writes JANAN GANESH in The FT

On a long-haul flight, Can You Ever Forgive Me? becomes the first film I have ever watched twice in immediate succession. Released last month in Britain, it recounts the (true) story of Lee Israel, a once-admired, now-marginal writer who resorts to literary forgery to make the rent on her fetid New York hovel. Her one friend is himself a washout who, as per the English tradition, passes off his insolvency as bohemia. Lee pleads with her agent to answer her calls and, in the rawest scene, confesses her crime with a wistful pang for the success it brought her.

There are serviceable jokes (including the profane farewell between the two friends) but the film is ultimately about failure: social, financial, romantic, professional. Put it down to the lachrymose effects of air travel — a phenomenon that has no definitive explanation — but I found the film unusually affecting. Or perhaps it was the shock of seeing failure addressed so unsentimentally, and from so many angles.

Failure — not spectacular failure, but failure as gnawing disappointment — is the natural order of life. Most people will achieve at least a little bit less than they would have liked in their careers. Most marriages wind down from intense passion to a kind of elevated friendship, and even this does not count the roughly four in 10 that collapse entirely. Most businesses fail. Most books fail. Most films fail.

You would hope that something so endemic to the human experience would be constantly discussed and actively prepared for. Instead, what we hear about is failure as a great “teacher”, or as a staging post before eventual success. There are management books about “failing forward”. There are educational methods that teach children the uses of failure. Consult an anthology of quotations about the subject, and it is not just the Paulo Coelho types who sugar-coat it. Churchill, Edison, Capote, at least one Roosevelt: people who should know better almost deny the existence of failure as anything other than a character-building phase.

There are good intentions behind all this. There is also a lot of naivety and squeamishness. For many people, failure will be just that, not a nourishing experience or a bridge to something else. It will be a lasting condition, and it will sting a fair bit.

Our seeming inability to look this fact in the eye is not just unbecoming in and of itself, it also inadvertently makes the experience of failure more harrowing than it needs to be. By reimagining it as just a holding pen before ultimate triumph, those who find themselves stuck there must feel like aberrations, when their experience could not be more banal.

I have known lots of Lee Israels: sensations at 25, under-achievers at 40. Sometimes, there was an identifiable wrong turn — a duff career move, say, or the pram in the hallway. But in most cases, it was just the law of numbers doing its impersonal work.

In almost all professions, there are too few places at the top for too many hopefuls. Lots of blameless people will miss out. Whether at school or through those excruciating management guides, a wiser culture would not romanticise failure as a means to success. It would normalise it as an end.

Look again at that list of names who have minted smarmy epigrams about the utility of failure. It is, you realise, a kind of winner’s wisdom. Those who overcome setbacks to achieve epic feats tend to universalise their atypical experience. Amazingly bad givers of advice, they encourage people to proceed with ambitions that are best sat on, and despise “quitters” when quitting is often the purest common sense.

At the end of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Lee is an unambiguous failure. There is (and you will excuse the spoilers) no rapprochement with an ex-lover she is plainly not over. There is no conquest of her drink habit. The film could dwell on the real-life Lee’s successful memoir, on which it is based, but only mentions it in text as the screen goes dark. She loses her solitary friend to illness. Even the cat croaks. Why, then, is the film so moreish as to demand an instant repeat over the Atlantic? It is, I think, the honest ventilation of a universal human subject. It is the novelty of being treated as a grown-up.

On a long-haul flight, Can You Ever Forgive Me? becomes the first film I have ever watched twice in immediate succession. Released last month in Britain, it recounts the (true) story of Lee Israel, a once-admired, now-marginal writer who resorts to literary forgery to make the rent on her fetid New York hovel. Her one friend is himself a washout who, as per the English tradition, passes off his insolvency as bohemia. Lee pleads with her agent to answer her calls and, in the rawest scene, confesses her crime with a wistful pang for the success it brought her.

There are serviceable jokes (including the profane farewell between the two friends) but the film is ultimately about failure: social, financial, romantic, professional. Put it down to the lachrymose effects of air travel — a phenomenon that has no definitive explanation — but I found the film unusually affecting. Or perhaps it was the shock of seeing failure addressed so unsentimentally, and from so many angles.

Failure — not spectacular failure, but failure as gnawing disappointment — is the natural order of life. Most people will achieve at least a little bit less than they would have liked in their careers. Most marriages wind down from intense passion to a kind of elevated friendship, and even this does not count the roughly four in 10 that collapse entirely. Most businesses fail. Most books fail. Most films fail.

You would hope that something so endemic to the human experience would be constantly discussed and actively prepared for. Instead, what we hear about is failure as a great “teacher”, or as a staging post before eventual success. There are management books about “failing forward”. There are educational methods that teach children the uses of failure. Consult an anthology of quotations about the subject, and it is not just the Paulo Coelho types who sugar-coat it. Churchill, Edison, Capote, at least one Roosevelt: people who should know better almost deny the existence of failure as anything other than a character-building phase.

There are good intentions behind all this. There is also a lot of naivety and squeamishness. For many people, failure will be just that, not a nourishing experience or a bridge to something else. It will be a lasting condition, and it will sting a fair bit.

Our seeming inability to look this fact in the eye is not just unbecoming in and of itself, it also inadvertently makes the experience of failure more harrowing than it needs to be. By reimagining it as just a holding pen before ultimate triumph, those who find themselves stuck there must feel like aberrations, when their experience could not be more banal.

I have known lots of Lee Israels: sensations at 25, under-achievers at 40. Sometimes, there was an identifiable wrong turn — a duff career move, say, or the pram in the hallway. But in most cases, it was just the law of numbers doing its impersonal work.

In almost all professions, there are too few places at the top for too many hopefuls. Lots of blameless people will miss out. Whether at school or through those excruciating management guides, a wiser culture would not romanticise failure as a means to success. It would normalise it as an end.

Look again at that list of names who have minted smarmy epigrams about the utility of failure. It is, you realise, a kind of winner’s wisdom. Those who overcome setbacks to achieve epic feats tend to universalise their atypical experience. Amazingly bad givers of advice, they encourage people to proceed with ambitions that are best sat on, and despise “quitters” when quitting is often the purest common sense.

At the end of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Lee is an unambiguous failure. There is (and you will excuse the spoilers) no rapprochement with an ex-lover she is plainly not over. There is no conquest of her drink habit. The film could dwell on the real-life Lee’s successful memoir, on which it is based, but only mentions it in text as the screen goes dark. She loses her solitary friend to illness. Even the cat croaks. Why, then, is the film so moreish as to demand an instant repeat over the Atlantic? It is, I think, the honest ventilation of a universal human subject. It is the novelty of being treated as a grown-up.

Americans really pay a bribe for a good education? In Britain, we’ve got far subtler ways

The deviousness that some routinely resort to here puts the US scandal in the shade writes Catherine Bennett in The Guardian

Actress Felicity Huffman has been indicted in the university admissions scandal. Photograph: David McNew/AFP/Getty Images

Ditto Smith’s generous quotation from a statement provided for a girl who has been reinvented, apparently for scam purposes, as a “US Club Soccer All American”: “On the soccer or lacrosse etc I am the one who looks like a boy amongst girls with my hair tied up, arms sleeveless, and blood and bruises from head to toe.”

Not, of course, that’s there’s anything illegal, here or in the US, about reproducing personal statements from professional suppliers or collaborating with a teacher and/or parent – the latter, though risibly unfair, is routine. Another Varsity Blues alleged tactic, that of buying a diagnosis requiring extra exam time, may have no exact UK parallel but, according to a 2017 BBC report, one in five children in independent schools received extra time for GCSE and A-levels. David Kynaston and David Green, in a powerful critique of independent schools, recently pointed out various advantages, made possible by high fees: “Far greater resources are available for diagnosing special needs, challenging exam results and guiding university applications.”

If, mercifully, UK universities are low on dependable side doors, the shamelessness of some of the US defendants, as they appear to pursue their imagined birthright (Ivy League bragging rights) can still sound uncomfortably familiar. Many British parents, equally fearful of mediocrity, are similarly unabashed on local tricks and stratagems – not only private education, but house moves, music lessons (for reserved school places), intensive coaching, internships, resits, religious conversions, fake addresses, and, the Times now reports, FOI requests to Oxbridge, from disappointed parents – that will end up, added to financial and cultural capital, delivering much the same outcome as the US scandal. Legal or otherwise, the result is enhanced educational opportunities for the privileged and untalented, fewer for the talented but disadvantaged.

The pervasive cunning is hardly surprising given the official esteem for “sharp-elbowed” parental operators, who, David Laws once argued, set a fine example. It follows, as demonstrated by UK politicians on all sides, that extreme resourcefulness in, say, keeping places from less fortunate residents, is readily passed off as understandable dedication as opposed to insatiable self-interest. Don’t we all want [smiling face with halo emoji] the best for our kids?

Following some unspecified epiphany, David Cameron, of previously wavering faith, secured places at an oversubscribed church school, some distance from No 10, requiring proof of “Sunday worship in a church at least twice a month for 36 months before the closing applications date”. Equally instructively, my own, affluent MP, Emily Thornberry, had, earlier, hoovered up three of the few precious places at an outstanding, part-selective school in Hertfordshire, 13 miles from home, which tradition annually reserves for her Islington constituents. On Twitter, she has reminded critics: “All my children educated in the state sector.” There is no suggestion that either MP has broken any laws.

There must be, beyond legality, some ethically significant factor that makes non-paying wangling infinitely superior to the ugly, US variety. But you probably have to buy a place at Harvard to find out what it is.

‘Emily Thornberry hoovered up three precious places at an outstanding part-selective school.’ Photograph: George Cracknell Wright/Rex/Shutterstock

“Dude, dude, what do you think, I’m a moron?” Thus, one of the parents accused of involvement in the US college bribery racket. He’d been warned – by a wiretapped conspirator – not to reveal that he paid $50,000 for his daughter’s fraudulent test results, part of a system the fixer calls “the side door”.

Appropriately soothed – “I’m not saying you’re a moron” – the accused father is recorded, by the FBI, assuring the scam’s organiser that he’ll deliver, if required, the agreed fiction. “I’m going to say that I’ve been inspired how you’re helping underprivileged kids get into college. Totally got it.”

Although many of the best bits of an FBI affidavit – presenting the case against the accused parents – have been widely circulated, this sublime page-turner deserves to be enjoyed in full, if not put up for literary awards pending film adaptation (Laura Dern has been suggested for Felicity Huffman), and made compulsory reading in all admission departments. It’s not just that extracts can’t convey the fathomless entitlement and mendacity exhibited by affluent, ostensibly respectable parents. They can’t begin to do justice to the affidavit’s entertainment value as savage social comedy, something productions of Molière often attempt, but rarely achieve.

Even the dramatis personae, in the investigation the FBI named “Operation Varsity Blues”, reads like an updated Tartuffe: “Todd Blake is an entrepreneur and investor. Diane Blake is an executive at a retail merchandising firm.” Here, too, cultivated, fluent people, many of whom also sound deluded, greedy and hypocritical, appear to be playing with their children’s lives for no reason beyond self-gratification. But the dialogue, when not jaw-dropping, races along (“And it works?” asks a defendant. “Every time.”), the plots and motives are horribly plausible, and the jeopardy is evidently real to the alleged conspirators, even if the all-encompassing irony of their alleged scheme is not. “She actually won’t really be part of the water polo team, right?”

And from a fellow future defendant, on the risks, if this status-enhancing, child-perfecting scam were to be discovered: “You know, the, the embarrassment to everyone in the communities. Oh my God, it would just be – yeah. Ugh.”

Are FBI affidavits regularly as good as the tale of Operation Varsity Blues? If so, the death of the novel should be easier to bear. Although this document has one overriding purpose – to show that accused parents and witnesses colluded in fraudulent applications – special thanks are due to special agent Laura Smith, the author, who never writes a dull page. Maybe the individual cases were fully as compelling as this edited evidence suggests. Or maybe agent Smith’s organisation of her material really does indicate considerable, dry artistry? Either way, you cherish the detail when an accused parent replies, following an allegedly fraudulently extracted college offer: “This is wonderful news! [high-five emoji].”

“Dude, dude, what do you think, I’m a moron?” Thus, one of the parents accused of involvement in the US college bribery racket. He’d been warned – by a wiretapped conspirator – not to reveal that he paid $50,000 for his daughter’s fraudulent test results, part of a system the fixer calls “the side door”.

Appropriately soothed – “I’m not saying you’re a moron” – the accused father is recorded, by the FBI, assuring the scam’s organiser that he’ll deliver, if required, the agreed fiction. “I’m going to say that I’ve been inspired how you’re helping underprivileged kids get into college. Totally got it.”

Although many of the best bits of an FBI affidavit – presenting the case against the accused parents – have been widely circulated, this sublime page-turner deserves to be enjoyed in full, if not put up for literary awards pending film adaptation (Laura Dern has been suggested for Felicity Huffman), and made compulsory reading in all admission departments. It’s not just that extracts can’t convey the fathomless entitlement and mendacity exhibited by affluent, ostensibly respectable parents. They can’t begin to do justice to the affidavit’s entertainment value as savage social comedy, something productions of Molière often attempt, but rarely achieve.

Even the dramatis personae, in the investigation the FBI named “Operation Varsity Blues”, reads like an updated Tartuffe: “Todd Blake is an entrepreneur and investor. Diane Blake is an executive at a retail merchandising firm.” Here, too, cultivated, fluent people, many of whom also sound deluded, greedy and hypocritical, appear to be playing with their children’s lives for no reason beyond self-gratification. But the dialogue, when not jaw-dropping, races along (“And it works?” asks a defendant. “Every time.”), the plots and motives are horribly plausible, and the jeopardy is evidently real to the alleged conspirators, even if the all-encompassing irony of their alleged scheme is not. “She actually won’t really be part of the water polo team, right?”

And from a fellow future defendant, on the risks, if this status-enhancing, child-perfecting scam were to be discovered: “You know, the, the embarrassment to everyone in the communities. Oh my God, it would just be – yeah. Ugh.”

Are FBI affidavits regularly as good as the tale of Operation Varsity Blues? If so, the death of the novel should be easier to bear. Although this document has one overriding purpose – to show that accused parents and witnesses colluded in fraudulent applications – special thanks are due to special agent Laura Smith, the author, who never writes a dull page. Maybe the individual cases were fully as compelling as this edited evidence suggests. Or maybe agent Smith’s organisation of her material really does indicate considerable, dry artistry? Either way, you cherish the detail when an accused parent replies, following an allegedly fraudulently extracted college offer: “This is wonderful news! [high-five emoji].”

Actress Felicity Huffman has been indicted in the university admissions scandal. Photograph: David McNew/AFP/Getty Images

Ditto Smith’s generous quotation from a statement provided for a girl who has been reinvented, apparently for scam purposes, as a “US Club Soccer All American”: “On the soccer or lacrosse etc I am the one who looks like a boy amongst girls with my hair tied up, arms sleeveless, and blood and bruises from head to toe.”

Not, of course, that’s there’s anything illegal, here or in the US, about reproducing personal statements from professional suppliers or collaborating with a teacher and/or parent – the latter, though risibly unfair, is routine. Another Varsity Blues alleged tactic, that of buying a diagnosis requiring extra exam time, may have no exact UK parallel but, according to a 2017 BBC report, one in five children in independent schools received extra time for GCSE and A-levels. David Kynaston and David Green, in a powerful critique of independent schools, recently pointed out various advantages, made possible by high fees: “Far greater resources are available for diagnosing special needs, challenging exam results and guiding university applications.”

If, mercifully, UK universities are low on dependable side doors, the shamelessness of some of the US defendants, as they appear to pursue their imagined birthright (Ivy League bragging rights) can still sound uncomfortably familiar. Many British parents, equally fearful of mediocrity, are similarly unabashed on local tricks and stratagems – not only private education, but house moves, music lessons (for reserved school places), intensive coaching, internships, resits, religious conversions, fake addresses, and, the Times now reports, FOI requests to Oxbridge, from disappointed parents – that will end up, added to financial and cultural capital, delivering much the same outcome as the US scandal. Legal or otherwise, the result is enhanced educational opportunities for the privileged and untalented, fewer for the talented but disadvantaged.

The pervasive cunning is hardly surprising given the official esteem for “sharp-elbowed” parental operators, who, David Laws once argued, set a fine example. It follows, as demonstrated by UK politicians on all sides, that extreme resourcefulness in, say, keeping places from less fortunate residents, is readily passed off as understandable dedication as opposed to insatiable self-interest. Don’t we all want [smiling face with halo emoji] the best for our kids?

Following some unspecified epiphany, David Cameron, of previously wavering faith, secured places at an oversubscribed church school, some distance from No 10, requiring proof of “Sunday worship in a church at least twice a month for 36 months before the closing applications date”. Equally instructively, my own, affluent MP, Emily Thornberry, had, earlier, hoovered up three of the few precious places at an outstanding, part-selective school in Hertfordshire, 13 miles from home, which tradition annually reserves for her Islington constituents. On Twitter, she has reminded critics: “All my children educated in the state sector.” There is no suggestion that either MP has broken any laws.

There must be, beyond legality, some ethically significant factor that makes non-paying wangling infinitely superior to the ugly, US variety. But you probably have to buy a place at Harvard to find out what it is.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)