San Pedro Sula, Honduras, is the most dangerous city on the planet – and experts say it is a sign of a global epidemic

It was relatively quiet in San Pedro Sula last month. A gunfight between police and a drug gang left a 15-year-old boy dead; the body of a man riddled with bullets was found in a banana plantation; two lawyers were gunned down; a salesman was murdered inside his 4x4; and a father and son were murdered at home after pleading not to be killed.

----Also read

----Also read

Humanity's 'inexorable' population growth is so rapid that even a global catastrophe wouldn't stop it

-----

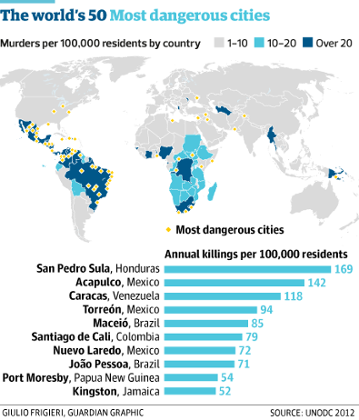

One politician survived an assassination attempt and around a dozen people were found dead in the street. The number of killings is said to have fallen in the last few months, but the Honduran city is officially the most violent in the world outside the Middle East and warzones, with more than 1,200 killings in a year, according to statistics for 2011 and 2012. Its murder rate of 169 per 100,000 people far surpasses anything in North America or much larger cities such as Johannesburg, Lagos or São Paulo. London, by contrast, has just 1.3 murders per 100,000 people.

Now research by security and development groups suggests that the violence plaguing San Pedro Sula – a city of just over a million, and Honduras’s second largest – and many other Latin American and African cities may be linked not just to the drug trade, extortion and illegal migration, but to the breakneck speed at which urban areas have grown in the last 20 years.

The faster cities grow, the more likely it is that the civic authorities will lose control and armed gangs will take over urban organisation, says Robert Muggah, research director at the Igarapé Institute in Brazil.

“Like the fragile state, the fragile city has arrived. The speed and acceleration of unregulated urbanisation is now the major factor in urban violence. A rapid influx of people overwhelms the public response,” he adds. “Urbanisation has a disorganising effect and creates spaces for violence to flourish,” he writes in a new essay in the journal Environment and Urbanization.

Muggah predicts that similar violence will inevitably spread to hundreds of other “fragile” cities now burgeoning in the developing world. Some, he argues, are already experiencing epidemic rates of violence. “Runaway growth makes them suffer levels of civic violence on a par with war-torn [cities such as] Juba, Mogadishu and Damascus,” he writes. “Places like Ciudad Juárez, Medellín and Port au Prince … are becoming synonymous with a new kind of fragility with severe humanitarian implications.”

Simon Reid-Henry, of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, said: “Today’s wars are more likely to be civil wars and conflict is increasingly likely to be urban. Criminal violence and armed conflict are increasingly hard to distinguish from one another in different parts of the world.”

The latest UN data shows that many cities may be as dangerous as war zones. While nearly 60,000 people die in wars every year, an estimated 480,000 are killed, mostly by guns, in cities. This suggests that humanitarian groups, which have traditionally focused on working in war zones, may need to change their priorities, argues Kevin Savage, a former researcher with the Overseas Development Institute in London.

“Some urban zones are fast becoming new territories of conflict and violence. Chronically violent cities like Abidjan, Baghdad, Kingston, Nablus, Grozny and Mogadishu are all synonyms for a new kind of armed conflict,” he said. “These urban centres are experiencing a variation of warfare, often in densely populated slums and shantytowns. All of them feature pitched battles between state and non-state armed groups and among armed groups themselves.”

European and North American cities, which mostly grew over 150 or more years, are thought unlikely to physically expand much in the next few decades and are likely to remain relatively safe; but urban violence is certain to worsen as African, Asian and Latin American cities swell with population growth and an unprecedented number of people move in from rural areas.

More than half the world now lives in cities compared with about 5% a century ago, and UN experts expect more than 70% of the world’s population to be living in urban areas within 30 years.

The fastest transition to cities is now occurring in Asia, where the number of city dwellers is expected to double by 2030, according to the UN Population Fund. Africa is expected to add 440 million people to its cities by then and Latin America and the Caribbean nearly 200 million. Rural populations are expected to decrease worldwide by 28 million people. Most urban growth is expected to be not in the world’s mega-cities of more than 10 million people, but in smaller cities like San Pedro Sula.

“We can expect no slowing down of urbanisation over the next 30 years. The youth bulge will go on and 90% of the growth will happen in the south,” said Muggah.

But he and other researchers have found that urban violence is not linked to poverty so much as inequality and impunity from the law – both of which may encourage lawlessness. “Many places are poor, but not violent. Some favelas in Brazil are among the safest places,” he said. “Slums are often far less dangerous than believed. There is often a disproportionate fear of crime relative to its real occurrence. Yet even when there is evidence to the contrary, most elites still opt to build higher walls to guard themselves.”

Many of these shantytowns and townships were now no-go areas far beyond the reach of public security forces, he said.

“These areas are stigmatised by the public authorities and residents become quite literally trapped. Cities like Caracas, Nairobi, Port Harcourt and San Pedro Sula are giving rise to landscapes of … gated communities. Violence … is literally reshaping the built environment in the world’s fragile cities.”