M J Akbar in The Times of India

After every terrorist outrage India asks a question that repeatedly withers on the dry sand of evasive clichés. How long will the apartheid of two laws for the same crime continue?

When America is stunned by 9/11, President George Bush pulverises Afghanistan, changes regime and exiles Taliban. When Paris is the scene of wanton murder, President François Hollande orders war machines to bomb regions held by ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

Neither goes into a brown study to ponder the causes of terrorism, a manipulative phrase designed specifically to provide cover for perpetrators of terrorism. Neither American nor French public opinion would accept such a pussyfoot leadership.

But when India is attacked by barbaric terrorists operating out of nearby sanctuaries, Washington and Paris, closely followed by London and Brussels, rush to Delhi to advise restraint. Why? Is an Indian life less valuable than an American or French life?

We need an answer.

There is one. I am not being unmindful of potential consequences in a nuclear-military zone, although at some point the big powers will have to grapple with the possibility of Pakistan’s tactical nuclear weapons finding their way into the hands of terrorists. The time has come for a war doctrine against terrorism that has no space for alibis.

Anyone who provides sanctuary to terrorists – whether individuals or governments – must be punished, swiftly and decisively, through collective military action and economic sanctions. There has to be a cost to hypocrisy.

We have a precedent. Perhaps predictably, it has been set by America. Washington has pursued and eliminated its terrorist enemies in half a dozen countries. The death of Osama bin Laden, who had been provided a secure home next to a large military establishment, was only the most dramatic instance.

How is Hafiz Saeed, living without a hint of remorse in Lahore, and planning more attacks while protected by state security, any less guilty? The United Nations has evidence against him, as has America. But Washington takes a nuanced view between those who attack America and those who target other nations. This is a compromise that cannot be sustained.

It is curious that a priest had clarity about Paris while politicians and pundits hedged. Pope Francis got it right when he called the ongoing conflict a ‘piecemeal third world war’. My qualification is that it merely seems piecemeal. Its impact is pervasive. Paris is attacked and every city feels instantly vulnerable. The purpose is achieved.

At this moment, conventional systems of security are still groping their way towards what precisely it is that they are fighting. The objective of terrorism is terror; to terrorise people and government through random mass killings. It exploits the very freedoms – of expression, communication, movement available in societies it targets.

It maximises impact with minimal investment in human capital; suicide missions are undertaken by young minds vulnerable to illusions about this life or the next. It exalts hatred as heroism.

The Geneva Convention was not written for a struggle against shadow armies that glorify mass murder or refuse to distinguish between war and peace. We need a doctrine for permanent war, and we need signatories that are ready to implement this doctrine with all the muscle at their command.

Walter Nicolai, the now forgotten head of Germany’s intelligence services during World War I, told his country that if it wanted to succeed it would have to adopt a new theory: ‘war in peace’. A hundred years later, this seems a relevant basis for an effective counteroffensive. But before we can solve the problem we must learn to recognise it. Fudge will not serve.

America cannot long continue a policy of selective punishment in a war that also afflicts its allies, friends and like-minded nations. It must accept what Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been saying repeatedly: There is no good terrorism and bad terrorism; terrorism is terrorism. To measure Osama and Hafiz by different yardsticks is akin to America saying that it would fight only Japan in World War II.

Terrorists are clear about who their enemy is: The ‘near enemy’ are those who challenge their ideas and politics within their own countries, hence the multiple civil wars; the ‘far enemy’ are those who support the ‘near enemy’, broadly the West, including Russia; and those who have ‘usurped Islamic space’, like China or India. Do we have equal clarity about terrorists?

Modi also noted that we must delink terrorism from religion. The refugees who are escaping their tortured homeland are also Muslim; in fact they are more honest Muslims than the deranged ‘jihadis’. We must learn something from this epic tragedy.

This is also a conflict between theocracy and democracy; between practitioners of faith-supremacy and believers in faith-equality as the basis of civilised behaviour. This war has to be fought at both military and ideological levels.

The answer to regression is not complicated: modernity. Modernity has four basic, non-negotiable principles. A modern nation must be democratic; it must believe in secularism; it must promote gender equality; and it must eliminate the curse of inequity and poverty. This is the charter for regions in chaos, which can save the future from ravages of the present.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday 18 November 2015

Tuesday 17 November 2015

France’s unresolved Algerian war sheds light on the Paris attack

Robert Fisk in The Independent

People weep as they gather to observe a minute-silence at the Place de la Republique in memory of the victims of the Paris terror attacksGetty

People weep as they gather to observe a minute-silence at the Place de la Republique in memory of the victims of the Paris terror attacksGettyIt wasn’t just one of the attackers who vanished after the Paris massacre. Three nations whose history, action – and inaction – help to explain the slaughter by Isis have largely escaped attention in the near-hysterical response to the crimes against humanity in Paris: Algeria, Saudi Arabia and Syria.

The French-Algerian identity of one of the attackers demonstrates how France’s savage 1956-62 war in Algeria continues to infect today’s atrocities. The absolute refusal to contemplate Saudi Arabia’s role as a purveyor of the most extreme Wahabi-Sunni form of Islam, in which Isis believes, shows how our leaders still decline to recognise the links between the kingdom and the organisation which struck Paris. And our total unwillingness to accept that the only regular military force in constant combat with Isis is the Syrian army – which fights for the regime that France also wants to destroy – means we cannot liaise with the ruthless soldiers who are in action against Isis even more ferociously than the Kurds.

Brother of Paris attack suspect has no idea where his brother is

Whenever the West is attacked and our innocents are killed, we usually wipe the memory bank. Thus, when reporters told us that the 129 dead in Paris represented the worst atrocity in France since the Second World War, they failed to mention the 1961 Paris massacre of up to 200 Algerians participating in an illegal march against France’s savage colonial war in Algeria. Most were murdered by the French police, many were tortured in the Palais des Sports and their bodies thrown into the Seine. The French only admit 40 dead. The police officer in charge was Maurice Papon, who worked for Petain’s collaborationist Vichy police in the Second World War, deporting more than a thousand Jews to their deaths.

Omar Ismail Mostafai, one of the suicide killers in Paris, was of Algerian origin – and so, too, may be other named suspects. Said and Cherif Kouachi, the brothers who murdered the Charlie Hebdo journalists, were also of Algerian parentage. They came from the five million-plus Algerian community in France, for many of whom the Algerian war never ended, and who live today in the slums of Saint-Denis and other Algerian banlieues of Paris. Yet the origin of the 13 November killers – and the history of the nation from which their parents came – has been largely deleted from the narrative of Friday’s horrific events. A Syrian passport with a Greek stamp is more exciting, for obvious reasons.

A colonial war 50 years ago is no justification for mass murder, but it provides a context without which any explanation of why France is now a target makes little sense. So, too, the Saudi Sunni-Wahabi faith, which is a foundation of the “Islamic Caliphate” and its cult-like killers. Mohammed ibn Abdel al-Wahab was the purist cleric and philosopher whose ruthless desire to expunge the Shia and other infidels from the Middle East led to 18th-century massacres in which the original al-Saud dynasty was deeply involved.

The present-day Saudi kingdom, which regularly beheads supposed criminals after unfair trials, is building a Riyadh museum dedicated to al-Wahab’s teachings, and the old prelate’s rage against idolaters and immorality has found expression in Isis’s accusation against Paris as a centre of “prostitution”. Much Isis funding has come from Saudis – although, once again, this fact has been wiped from the terrible story of the Friday massacre.

Francois Hollande announces plans to change extend anti-terror powers

And then comes Syria, whose regime’s destruction has long been a French government demand. Yet Assad’s army, outmanned and still outgunned – though recapturing some territory with the help of Russian air strikes – is the only trained military force fighting Isis. For years, both the Americans, the British and the French have said that the Syrians do not fight Isis. But this is palpably false; Syrian troops were driven out of Palmyra in May after trying to prevent Isis suicide convoys smashing their way into the city – convoys that could have been struck by US or French aircraft. Around 60,000 Syrian troops have now been killed in Syria, many by Isis and the Nusrah Islamists – but our desire to destroy the Assad regime takes precedence over our need to crush Isis.

The French now boast that they have struck Isis’s Syrian “capital” of Raqqa 20 times – a revenge attack, if ever there was one. For if this was a serious military assault to liquidate the Isis machine in Syria, why didn’t the French do it two weeks ago? Or two months ago? Once more, alas, the West – and especially France – responds to Isis with emotion rather than reason, without any historical context, without recognising the grim role that our “moderate”, head-chopping Saudi “brothers” play in this horror story. And we think we are going to destroy Isis...

A bird’s eye view of terror

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

DIWALI pollution sends droves of Delhi residents scouring for somewhere to breathe. I thus learnt of the Paris outrage watching migratory birds 190 kilometres from the country’s smog capital, off the Agra highway. Sharing the news with a French couple at the Bharatpur avian sanctuary that morning offered a learning curve. They were from the embassy in Delhi. The man scanned the BBC bullet points on my mobile phone and translated the story to his wife. He then took a deep breath, shrugged his shoulders wryly and resumed fixing the telescope on a steel tripod.

The couple had seen a gaggle of rare ducks on the far side of the sanctuary the previous morning, the Frenchman informed me helpfully. The woman sat down silently on a bench atop the watchtower, where we met, as she resumed observing the cormorants in flight. Her knitted eyebrows were a giveaway though to concealed emotion.

That afternoon, in Delhi, still trying to figure out the composed response of the French couple to what I thought was a shocking carnage in their country, I scanned some more of the news. The approach of so many French people was uniformly similar to that of the two bird watchers of Bharatpur.

As Parisians struggled to make sense of their new reality, a report in the New York Times described parents whose children slept through the ordeal while they grappled to fudge the explanation to offer them in the morning why so many planned activities had been cancelled.

To my Indian sensibilities so used to one prime minister declaring aar-paar ki ladai (a fight to the finish) and another flaunting his supposedly 56-inch chest in response to terror provocations, the philosophical demeanour of Bertrand Bourgeois, a 42-year old French accountant, was eye-catching.

He was lost in thought as he cast a fishing line beneath the Invalides bridge. Bourgeois, the NYT told us, normally avoids fishing in Paris. Instead, he preferred the quieter sections of the Seine near his home in Poissy. But after the violence, he said he felt drawn to come into the city out of a sense of solidarity.

What an amazing response compared with the televised clamour in India after a similar attack on Mumbai. Shrill opinion vendors called Prime Minister Manmohan Singh a weakling for refusing to carpet-bomb Pakistan. Singh saw through the insane chorus, as did the ordinary Indian people. They elected him for a second consecutive term just for keeping his nerve and for continuing to talk to Pakistan.

Drum beaters of war anywhere might want to benefit from the insights of Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari.

“As the literal meaning of the word indicates, terror is a military strategy that hopes to change the political situation by spreading fear rather than by causing material damage,” Harari wrote in The Guardian after the Paris attacks. “This strategy is almost always adopted by very weak parties, who are unable to inflict much material damage on their enemies.”

Whatever be the score of the casualties inflicted by an act of terror it can never be even a fraction of the losses from a conventional war. “On the first day of the battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, 19,000 members of the British army were killed and another 40,000 wounded,” reminded the author of the international bestseller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.

“By the time the battle ended in November, both sides together had suffered more than a million casualties, which included 300,000 dead. Yet this unimaginable carnage hardly changed the political balance of power in Europe. It took another two years and millions of additional casualties for something finally to snap.”

What was the reaction of President Hollande to the coordinated strikes in Paris? He threatened merciless retribution, but against who? If helpless Syrian or other refugees get caught in the crossfire between the government and the terrorists, well that’s playing to the wrong script.

To avenge the Paris attacks, French warplanes carried out heavy bombardments of the militant group that calls itself Islamic State. Should they not have been doing the bombings without the Paris carnage as justification? Would the terror command centres and fuel hubs not be touched if Paris were not attacked? Hollande can do no more than look over his shoulder to see the Le Pens and the Sarkozys mock him. But that is not the point.

Western powers have struck up a compromise with Russian President Putin for a coordinated strategy in Syria. Have the terrorists in Paris inadvertently cooked the goose of Kiev? What are the chances that a number of states in the Middle East that were seen as a source of strength to the Islamists, led by Israel and Saudi Arabia, accept the conditions implicit in a no-holds-barred targeting of Daesh?

In any case, what is in store in all this for South Asia, more so for Pakistan? We have discussed the hypocrisy of delinking Al Nusra from Al Qaeda. How many shades of extremists has Pakistan got in its arsenal to deal with India and Afghanistan or even Iran? Will a school in Peshawar remain more worthy of protection from future harm than schools in the neighbourhood?

As I was leaving the bird sanctuary, a guide pointed to a row of marble tablets with names embossed of viceroys, maharajas and even of Gen J.N. Chaudhuri. They had shot helpless migratory birds for sport. Lord Linlithgow — 4,273 birds with 39 guns led the field. Gen Chaudhuri shot 556 birds for half a day with 51 guns. That was in September 1964. Had the India-Pakistan war broken out a year before it did, at least the birds might have been spared a predatory assault. Such is the circuitous logic of terror and its remedies. Most people seem to know this though their governments may not.

Sunday 15 November 2015

India is more sensitive now, not more intolerant

Swaminathan Anklesaria Aiyer in the Times of India

Narendra Modi said in London that “India will not tolerate intolerance”. Secular critics jeered, since the BJP had raised the communal temperature during the Bihar election. Over 50 writers have returned national awards in protest against intolerance. They cite the Dadri beef lynching, murder of three prominent writers, and the ink attack on Sudheendra Kulkarni.

But it’s fiction to pretend that India used to be tolerant and has turned intolerant today. Intolerance has actually diminished substantially. Nothing can compare with the communal killings at Partition in 1947. Communal riots have continued with sickening regularity since then, but diminished in recent years, with the notable exception of 2002.

Ambedkar said violence against dalits was the worst of all. The Indian Constitution banned caste discrimination, yet caste violence remained embedded in society. Dalits could be attacked, raped, killed and humiliated at will, with impunity, by upper castes. This was also true, to a lesser extent, of other backward castes. Villages did not have riots, yet their very ethos was based on the most oppressive threat of caste violence. Fortunately, caste discrimination has fallen gradually, though it remains a harsh reality. The last two decades have seen the rise of almost 4,000 dalit millionaire businessmen, something unthinkable in the past.

Modi will never be forgiven by many for the 2002 Gujarat riots. But JS Bandukwala, the Muslim professor who barely escaped mob murder, told me that the 1969 Gujarat riots were worse. Yet the then Congress chief minister did not resign or become a social pariah. Regional newspapers relegated many of the 1969 incidents to inside pages.

Why? What has changed? The answer is the rise of private TV. This has brought the awfulness of communal violence into every household in every language. In 1969, there was no TV. All India Radio had a radio monopoly. The government deliberately played down the riots, to try and reduce communal tension. Newspapers those days had shoestring budgets. Reporters did not rush from all corners of India to Gujarat, or go into every affected town. Most newspapers depended on briefings from the home ministry, and co-operated with government pleas to play down killings, to douse communal tensions. No photos were published of the blood and gore. Newspapers avoided saying “Hindu” or “Muslim,” and just said “people of another community”.

Media reportage was stronger during the Babri Masjid agitation. But there was no private TV in 1992 to expose the gore and violence of the masjid destruction, or the horrific post-masjid riots.

By the 2002 riots in Gujarat, a media revolution had occurred. Private TV channels with ample resources sent reporters to every riot site. They competed in exposing communal hate and gore. Far from hiding the identity of communities, TV highlighted the Hindu-Muslim divide starkly. Far from trying to douse tension, TV competed in highlighting horrific events, including even fictions like the supposed pregnant woman whose womb was slit by Hindu fanatics.

Did the aggressive media in 2002 increase communal tensions and violence compared with 1969? Quite possibly. Yet the media were right to pull no punches. By conveying the horror of 2002 all over India, they created a revulsion that Modi himself heeded in his next 12 years in Gujarat. Subsequently too, media competition greatly increased coverage of all sorts of discrimination and violence. Events once buried in the inside pages of newspapers became prime time TV news. This improved public sensitivity to discrimination and thuggery, and hence government accountability.

The BJP says it is being treated unfairly today, since there have been a few stray communal incidents but no riots. The BJP was not behind the Dadri or Jammu lynchings, or the killing of rationalist writers, and was actually a victim in the ink-throwing incident. However, BJP spokesmen have found it almost impossible to condemn these incidents outright, and sought to convert the cow into a vote-gaining tactic in Bihar. This BJP hypocrisy has rightly been condemned. Yet its current sins are absolutely nothing compared with 1992 or 2002.

Intolerance has not worsened. Rather, our civic standards have improved, and we are quicker to get disgusted. Competitive TV has made us much more easily horrified, terrified, alarmed, disgusted, and angry. That’s an excellent development. Private TV has not just improved entertainment and variety, but also hugely increased our sensitivity to all that’s wrong in society, to all its horrors and atrocities.

This is a major gain of economic liberalization. In 1991, leftists opposed private TV channels, saying these would be tools in the hands of big business. What rubbish. Private TV has empowered the citizen to view the horrors that government channels had always downplayed and sanitized. That has raised our civic standards, lowering our thresholds for anger and revulsion. Hurrah!

Saturday 14 November 2015

The global economy is slowing down. But is it recession – or protectionism?

Heather Stewart and Fergus Ryan in The Guardian

For one Chinese company that depends on global trade, fears over the worldwide economy have come to pass already. “The global economy is pretty bleak at the moment,” says Luo Dong, the owner of Doyoung, a Beijing-based exporter of frozen seafood and fruit. “This is having a big effect on us. Our clients’ sales are a lot slower than they used to be, and as purchasing power overseas drops, our exports are taking a hit.”

Luo’s observations were echoed on a wider stage last week, when the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development voiced the fear gripping many economists: that the drop-off in trade, driven by China, may be a harbinger of something more worrying – a global recession.

Days later, Rolls-Royce became the latest British exporter to face what it called “headwinds” from China, joining a slew of others, from carmaker Jaguar Land Rover to luxury brand Burberry. Meanwhile, commodities including platinum and crude oil resumed their decline in value as investors continued to fret about sliding demand for the raw materials of global commerce. Beijing has cut interest rates six times in less than a year and let the yuan slide against the dollar, underlining the sense of alarm about slowing growth.

Official figures show GDP expanding at around 6.9% in the world’s second-largest economy, conveniently in line with the government’s official target of “around 7%”; but outside analysts believe it may be much weaker. “We find these numbers pretty implausible,” says Andrew Brigden of City consultancy Fathom. “China is slowing a lot more markedly than the official figures show.” Fathom’s calculations, based on alternative indicators such as electricity use, suggest GDP growth of 3% or even less.

However, inside China it feels as though sluggish demand from the eurozone, rather than a homegrown problem, is to blame for the deterioration in the economic weather.

Luo, whose company exports to the US, Europe, Middle East and Africa, says exports have roughly halved since last year. “The worst market has been Europe, largely due to exchange rate fluctuations,” he says.

The European Central Bank has deliberately driven down the value of the single currency by implementing quantitative easing. “The other major factor has been labour costs here, which have gone up about a third,” Luo adds.

For the UK, so far, the impact of global trade headwinds has been relatively mild, notwithstanding the tone of alarm from exporters. Lee Hopley, chief economist at the UK manufacturers’ association EEF, says: “It’s something that’s certainly on our members’ radar, and it’s a source of concern.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest Angel Gurría of the OECD: ‘Global trade, which was already growing slowly over the past few years, appears to have stagnated.’ Photograph: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images

But for a string of other countries, especially those heavily dependent on commodities exports, the result has been economic chaos – and the OECD fears worse may be to come. After the great financial crisis hit in 2008, reports that demand for exports had “fallen off a cliff”, as it was often put at the time, were among the first signals that a deep downturn was under way.

“Global trade, which was already growing slowly over the past few years, appears to have stagnated,” said Angel Gurría, the OECD’s secretary general, presenting its latest economic forecasts and predicting trade growth of around 2% this year. “What happened in the past 50 years whenever there was such a slowdown in trade growth, it was a harbinger of a very sharp turn of the economy for the worse.”

Gurría explained that the recent slowdown in emerging market economies, led by China, had been particularly damaging because it had come at a time when the advanced economies, in particular the eurozone and Japan, were not yet growing at a robust enough pace to drive global growth.

“A further sharp slowdown in emerging market economies is weighing down on activity and trade. At the same time, subdued investment and productivity growth are checking the momentum of the recovery in advanced economies. It’s a double whammy,” Gurría said.

The OECD’s prescription for this malaise is a collective effort by the advanced economies to ramp up investment – helping to boost demand, improve productivity and generate stronger growth. A similar approach was set out by President Barack Obama on Friday, and he is likely to press for more action to prop up domestic demand at this weekend’s G20 meeting in Turkey.

But with Germany and the UK still enthusiastically espousing austerity, any commitment to new investment seems highly unlikely; so economists have been left trying to count the costs of China’s transition from high-speed, export-led growth to a new economic model at a time when demand in other markets is far from booming.

Economist and China-watcher George Magnus reckons the world will avoid recession, but the damage will be severe for economies that have hitched themselves to the Chinese bandwagon in recent years.

“In Africa, exports to China are 12% of total exports, but three-quarters of the exposure is concentrated among five countries: Angola, South Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea,” he said in a recent blogpost. “In Australia, exports to China are a third of total exports. In Latin America, exports to China are about 2% of regional GDP.”

Most of these countries are exporters of coal, oil and minerals, and their struggles coincide with the end of what became known as the “commodities supercycle” – a decade or so in which prices were held aloft by the belief that demand for raw materials would continue rising, as developing economies became the engines of global growth.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Protests in Brazil, which is now in recession. Photograph: Imago/Barcroft Media

Goldman Sachs’s decision to close down its loss-making Bric fund was a symbolic reminder that the days are gone when the economic rise of Brazil, Russia, India and China (the four countries from which the fund drew its name) seemed guaranteed. Indeed, Brazil and Russia are both in recession.

The US Federal Reserve’s plans to raise interest rates from near zero, which many experts now expect to happen next month, could deepen the agony of countries already struggling with plunging currencies and rising borrowing costs. The International Monetary Fund has warned of a flurry of bankruptcies in emerging economies as rates rise.

“A lot of these countries haven’t been helping themselves: Taiwan, Korea; they’ve all been cranking up their own credit growth,” says Russell Jones of Llewellyn Consulting, an economics advisory firm. But he too believes the world should escape a general slump. “I don’t think we’re on the cusp of a major downturn — probably more of the same.”

Simon Evenett of St Gallen University in Switzerland, who collates detailed data for the thinktank Global Trade Alert, offers an alternative explanation for the recent slide in trade volumes. He calculates that about half of the fall, since exports peaked in September last year, has been caused by the commodity price rout; but the rest, rather than evidence of sickly global demand, has resulted from a creeping rise in protectionism.

His analysis suggests the declines have overwhelmingly taken place in just 28 categories of product. “That’s very concentrated; that makes me doubt that it’s a global downturn.” Eight of these categories are commodities; but the rest map closely on to areas where countries have taken protectionist measures.

In the wake of the financial crisis, policymakers from the G20 countries pledged not to resort to the tit-for-tat protectionism that led to collapsing trade volumes in the wake of the Great Crash of 1929, and was ultimately seen as a contributor to the Great Depression. Since then, there has been little sign of anything with the scope of America’s Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which slapped import tariffs on more than 800 products.

But Evenett says there has been a flurry of more subtle manoeuvres: restricting public procurement to domestic firms, for example, or quietly tightening regulations to raise the bar against imports. “I think the China story is adding spice to it, but I think there’s more going on here,” he says.

He is concerned that unless action is taken, politicians will continue to throw sand in the wheels of the international trading system. If he’s right, the downturn seen so far may not be sending a warning signal about global demand; instead, it would be best read as a measure of the fragility of globalisation.

For one Chinese company that depends on global trade, fears over the worldwide economy have come to pass already. “The global economy is pretty bleak at the moment,” says Luo Dong, the owner of Doyoung, a Beijing-based exporter of frozen seafood and fruit. “This is having a big effect on us. Our clients’ sales are a lot slower than they used to be, and as purchasing power overseas drops, our exports are taking a hit.”

Luo’s observations were echoed on a wider stage last week, when the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development voiced the fear gripping many economists: that the drop-off in trade, driven by China, may be a harbinger of something more worrying – a global recession.

Days later, Rolls-Royce became the latest British exporter to face what it called “headwinds” from China, joining a slew of others, from carmaker Jaguar Land Rover to luxury brand Burberry. Meanwhile, commodities including platinum and crude oil resumed their decline in value as investors continued to fret about sliding demand for the raw materials of global commerce. Beijing has cut interest rates six times in less than a year and let the yuan slide against the dollar, underlining the sense of alarm about slowing growth.

Official figures show GDP expanding at around 6.9% in the world’s second-largest economy, conveniently in line with the government’s official target of “around 7%”; but outside analysts believe it may be much weaker. “We find these numbers pretty implausible,” says Andrew Brigden of City consultancy Fathom. “China is slowing a lot more markedly than the official figures show.” Fathom’s calculations, based on alternative indicators such as electricity use, suggest GDP growth of 3% or even less.

However, inside China it feels as though sluggish demand from the eurozone, rather than a homegrown problem, is to blame for the deterioration in the economic weather.

Luo, whose company exports to the US, Europe, Middle East and Africa, says exports have roughly halved since last year. “The worst market has been Europe, largely due to exchange rate fluctuations,” he says.

The European Central Bank has deliberately driven down the value of the single currency by implementing quantitative easing. “The other major factor has been labour costs here, which have gone up about a third,” Luo adds.

For the UK, so far, the impact of global trade headwinds has been relatively mild, notwithstanding the tone of alarm from exporters. Lee Hopley, chief economist at the UK manufacturers’ association EEF, says: “It’s something that’s certainly on our members’ radar, and it’s a source of concern.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest Angel Gurría of the OECD: ‘Global trade, which was already growing slowly over the past few years, appears to have stagnated.’ Photograph: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images

But for a string of other countries, especially those heavily dependent on commodities exports, the result has been economic chaos – and the OECD fears worse may be to come. After the great financial crisis hit in 2008, reports that demand for exports had “fallen off a cliff”, as it was often put at the time, were among the first signals that a deep downturn was under way.

“Global trade, which was already growing slowly over the past few years, appears to have stagnated,” said Angel Gurría, the OECD’s secretary general, presenting its latest economic forecasts and predicting trade growth of around 2% this year. “What happened in the past 50 years whenever there was such a slowdown in trade growth, it was a harbinger of a very sharp turn of the economy for the worse.”

Gurría explained that the recent slowdown in emerging market economies, led by China, had been particularly damaging because it had come at a time when the advanced economies, in particular the eurozone and Japan, were not yet growing at a robust enough pace to drive global growth.

“A further sharp slowdown in emerging market economies is weighing down on activity and trade. At the same time, subdued investment and productivity growth are checking the momentum of the recovery in advanced economies. It’s a double whammy,” Gurría said.

The OECD’s prescription for this malaise is a collective effort by the advanced economies to ramp up investment – helping to boost demand, improve productivity and generate stronger growth. A similar approach was set out by President Barack Obama on Friday, and he is likely to press for more action to prop up domestic demand at this weekend’s G20 meeting in Turkey.

But with Germany and the UK still enthusiastically espousing austerity, any commitment to new investment seems highly unlikely; so economists have been left trying to count the costs of China’s transition from high-speed, export-led growth to a new economic model at a time when demand in other markets is far from booming.

Economist and China-watcher George Magnus reckons the world will avoid recession, but the damage will be severe for economies that have hitched themselves to the Chinese bandwagon in recent years.

“In Africa, exports to China are 12% of total exports, but three-quarters of the exposure is concentrated among five countries: Angola, South Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea,” he said in a recent blogpost. “In Australia, exports to China are a third of total exports. In Latin America, exports to China are about 2% of regional GDP.”

Most of these countries are exporters of coal, oil and minerals, and their struggles coincide with the end of what became known as the “commodities supercycle” – a decade or so in which prices were held aloft by the belief that demand for raw materials would continue rising, as developing economies became the engines of global growth.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Protests in Brazil, which is now in recession. Photograph: Imago/Barcroft Media

Goldman Sachs’s decision to close down its loss-making Bric fund was a symbolic reminder that the days are gone when the economic rise of Brazil, Russia, India and China (the four countries from which the fund drew its name) seemed guaranteed. Indeed, Brazil and Russia are both in recession.

The US Federal Reserve’s plans to raise interest rates from near zero, which many experts now expect to happen next month, could deepen the agony of countries already struggling with plunging currencies and rising borrowing costs. The International Monetary Fund has warned of a flurry of bankruptcies in emerging economies as rates rise.

“A lot of these countries haven’t been helping themselves: Taiwan, Korea; they’ve all been cranking up their own credit growth,” says Russell Jones of Llewellyn Consulting, an economics advisory firm. But he too believes the world should escape a general slump. “I don’t think we’re on the cusp of a major downturn — probably more of the same.”

Simon Evenett of St Gallen University in Switzerland, who collates detailed data for the thinktank Global Trade Alert, offers an alternative explanation for the recent slide in trade volumes. He calculates that about half of the fall, since exports peaked in September last year, has been caused by the commodity price rout; but the rest, rather than evidence of sickly global demand, has resulted from a creeping rise in protectionism.

His analysis suggests the declines have overwhelmingly taken place in just 28 categories of product. “That’s very concentrated; that makes me doubt that it’s a global downturn.” Eight of these categories are commodities; but the rest map closely on to areas where countries have taken protectionist measures.

In the wake of the financial crisis, policymakers from the G20 countries pledged not to resort to the tit-for-tat protectionism that led to collapsing trade volumes in the wake of the Great Crash of 1929, and was ultimately seen as a contributor to the Great Depression. Since then, there has been little sign of anything with the scope of America’s Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which slapped import tariffs on more than 800 products.

But Evenett says there has been a flurry of more subtle manoeuvres: restricting public procurement to domestic firms, for example, or quietly tightening regulations to raise the bar against imports. “I think the China story is adding spice to it, but I think there’s more going on here,” he says.

He is concerned that unless action is taken, politicians will continue to throw sand in the wheels of the international trading system. If he’s right, the downturn seen so far may not be sending a warning signal about global demand; instead, it would be best read as a measure of the fragility of globalisation.

Thursday 12 November 2015

Saudi Arabia risks destroying Opec and feeding the Isil monster

'Saudi Arabia is acting directly against the interests of half the cartel and is running Opec over a cliff,' says RBC

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in the Telegraph

The rumblings of revolt against Saudi Arabia and the Opec Gulf states are growing louder as half a trillion dollars goes up in smoke, and each month that goes by fails to bring about the long-awaited killer blow against the US shale industry.

"Saudi Arabia is acting directly against the interests of half the cartel and is running Opec over a cliff"

Helima Croft, RBC Capital Markets

Algeria's former energy minister, Nordine Aït-Laoussine, says the time has come to consider suspending his country's Opec membership if the cartel is unwilling to defend oil prices and merely serves as the tool of a Saudi regime pursuing its own self-interest. "Why remain in an organisation that no longer serves any purpose?" he asked.

Saudi Arabia can, of course, do whatever it wants at the Opec summit in Vienna on December 4. As the cartel hegemon, it can continue to flood the global market with crude oil and hold prices below $50.

It can ignore desperate pleas from Venezuela, Ecuador and Algeria, among others, for concerted cuts in output in order to soak the world glut of 2m barrels a day, and lift prices to around $75. But to do so is to violate the Opec charter safeguarding the welfare of all member states.

"Saudi Arabia is acting directly against the interests of half the cartel and is running Opec over a cliff. There could be a total blow-out in Vienna," said Helima Croft, a former oil analyst at the US Central Intelligence Agency and now at RBC Capital Markets.

The Saudis need Opec. It is the instrument through which they leverage their global power and influence, much as Germany attains world rank through the amplification effect of the EU.

The 29-year-old deputy crown prince now running Saudi Arabia, Mohammad bin Salman, has to tread with care. He may have inherited the steel will and vaulting ambitions of his grandfather, the terrifying Ibn Saud, but he has ruffled many feathers and cannot lightly detonate a crisis within Opec just months after entangling his country in a calamitous war in Yemen. "It would fuel discontent in the Kingdom and play to the sense that they don't know what they are doing," she said.

"We are feeling the pain and we’re taking it like a God-driven crisis"

Mohammed Bin Hamad Al Rumhy, Oman's oil minister

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the oil price crash has cut Opec revenues from $1 trillion a year to $550bn, setting off a fiscal crisis that has already been going on long enough to mutate into a bigger geostrategic crisis.

Mohammed Bin Hamad Al Rumhy, Oman's (non-Opec) oil minister, said the Saudi bloc has blundered into a trap of their own making - a view shared by many within Saudi Arabia itself.

“If you have 1m barrels a day extra in the market, you just destroy the market. We are feeling the pain and we’re taking it like a God-driven crisis. Sorry, I don’t buy this, I think we’ve created it ourselves,” he said.

The Saudis tell us with a straight face that they are letting the market set prices, a claim that brings a wry smile to energy veterans. One might legitimately suspect that they will revert to cartel practices when they have smashed their rivals, if they succeed in doing so.

One might also suspect that part of their game is to check the advance of solar and wind power in a last-ditch effort to stop the renewable juggernaut and win another reprieve for the status quo. If so, they are too late. That error was made five or six years ago when they allowed oil prices to stay above $100 for too long. But Opec can throw sand in the wheels.

At root is a failure to grasp how quickly the ground has already shifted from under the feet of the petro-rentier regimes. Opec forecasts that oil demand will keep rising relentlessly, adding 21m barrels of oil per day (b/d) to 111m by 2040 as if nothing had changed. They have their heads in the sand.

The climate pledges made for the COP21 summit in Paris by the US, China and India - to name a few - imply a radical shift in the global energy landscape. Subsequent deals by 2025 may well bring a "two degree world" within sight.

The IEA says oil demand will be just 103m b/d in 2040 even under modest carbon curbs. It would collapse to 83.4m b/d if global leaders grasp the nettle. My own view is that it will happen by natural market forces.

The next leap foward in technology is going to be in energy storage. Teams of scientists at Harvard, MIT and the world's elite universities are in a race to slash the cost of batteries - big and small - and overcome the curse of intermittency for wind and solar.

A team in Cambridge says it has cracked the technology for lithium-air batteries that cut costs by four-fifths and enable car journeys of hundreds of miles on a single charge. By the time we reach 2040, it is a fair bet the only petrol cars still on the road will be relics, if they can find fuel at all.

"Everything will be electrified. The internal combustion engine is a dead-end. We all know that, and the car companies ought to know that," said one official handling the COP21 talks.

Opec might be better advised to target prices of $75 to $80 and maximize revenues while it still can, taking advantage of a last window to break reliance on energy and diversify their economies.

The current war of attrition against shale is a hard slog. US output has dropped by 500,000 b/d since April, but the fall in October slowed to 40,000 b/d. Total production of 9.1m b/d is roughly where it was a year ago when the price war began.

"The expectation that a swift tailing-off in tight oil would lead to a rapid rebalancing in the market has proved to be misplaced," said the IEA. Costs are plummeting as rig fees drop and drilling time is slashed.

There is a time-lag effect. Shale cannot keep switching to high-yielding wells forever. Their hedging contracts are running out. The US energy departmentexpects a further erosion of 600,000 b/d next year, but this is not a collapse.

By then Opec will have foregone another half trillion dollars. "What is winning supposed to look like for the Saudis? Can they really endure another year of this?" said Ms Croft.

Opec can certainly bankrupt high-debt frackers but this does not shut down US shale in any meaningful way. The infrastructure and technology will remain. Stronger players will move in. Output will bounce back as soon as oil nears $60.

Shale frackers will respond with lightning speed to any rebound and create a permanent headwind for Opec over years to come, or a sort of "whack-a-mole" effect, contrary to warnings by the IEA this week that Mid-East producers may regain their 1970s stranglehold once rivals are cleared out.

What is clear is that the Opec squeeze has killed off $200bn of upstream oil investment, mostly in offshore projects, Canadian oil sands and Arctic ventures. That will cut oil output in the distant future, but it is a different story.

Saudi Arabia has certainly regained market share, but the cost is causing many in Riyadh to ask whether the brash new team in power has thought through the trade-off. While the Kingdom has deep pockets, they are not limitless. Kuwait, Qatar and Abu Dhabi all have foreign reserves that are three higher per capita.

It has been downgraded to A+ by Standard & Poor's and has a budget deficit of $100bn a year, forcing it to burn through reserves at a commensurate pace and now to tap the global bond market.

Austerity has finally arrived, a nasty shock that was not in the original plan. A confidential order from King Salman - marked "highly urgent" - has frozen new hiring by the state, stopped property contracts and purchases of cars, and halted a long list of projects. The Kingdom will have to slim down the edifice of subsidies and social patronage that keeps the lid on protest.

It is far from clear whether Saudi Arabia can continue to prop up allies in the region and bankroll Egypt, already struggling to defeat Isil forces in the Sinai. An Isil cell captured - and beheaded - a Croatian engineer on the outskirts of Cairo in August, even before the suspected bombing of a Russian airline this month.

The Isil brand has established a front in Libya and has launched attacks in Algeria, where the old regime is fraying, and oil and gas revenues fund the vitally-needed social welfare net.

Iraq is pumping oil a record pace but it is nevertheless spiraling into economic crisis, with a budget deficit of 23pc of GDP. Public sector wages are to be cut. The austerity budget for 2016 - based on $45 oil, down from $80 last year - has set off a political storm.

The government has slashed funding for the "Popular Mobilization" militia fighting Isil. "The Iraqi state faces a grave challenge. The budget crisis makes the status quo intractable," says Patrick Martin from the Institute for the Study of War.

Helima Croft says Isil is now operating close to Iraq's oil facilities near Basra, detonating a car bomb at a market in Zubayr last month. They clearly have the ability to attack energy targets, and have an incentive to do so since oil production within their Caliphate heartland is their main source of income.

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb showed it could launch a devastating surprise when it crossed into the Sahara two years ago and seized the Amenas gas facility in Algeria, killing 39 foreign hostages. Variants of Isil can strike anywhere they find a weak link.

"We remain concerned that they may eventually set their sights on a major oil facility. These are obvious targets of choice, and none of this geopolitical risk is priced into the market," she said.

Saudi Arabia itself is vulnerable. There have been five Isil-linked terrorist acts on Saudi soil since May. They include an attack on a security facility near the giant oil installation at Abqaiq, where clusters of pipelines offer the most inviting sabotage target in the petroleum world and where the aggrieved Shia minority sit on the Kingdom's oil reserves.

It would be a macabre irony if Saudi Arabia's high-risk oil strategy so enflamed a region already in the grip of four civil wars that the Kingdom was hoisted by its own petard. That would certainly clear the global glut of crude oil.

Batting:The downside of up

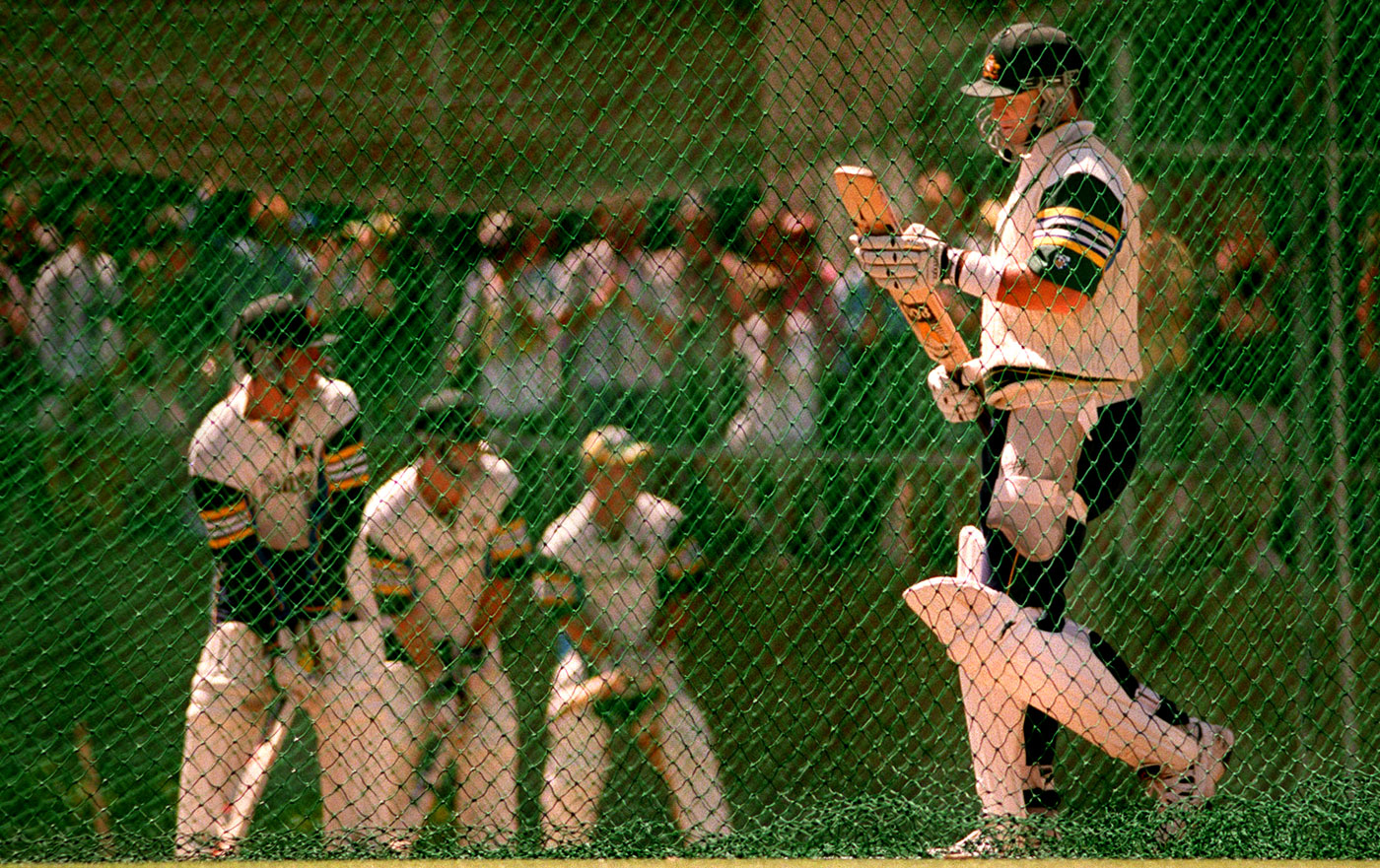

Grounded for life: Justin Langer at the Gabba© Getty Images

What began as a technical tweak for one Aussie batsman is now a nationwide fad. And not everyone is impressed

SB TANG in Cricinfo | NOVEMBER 2015

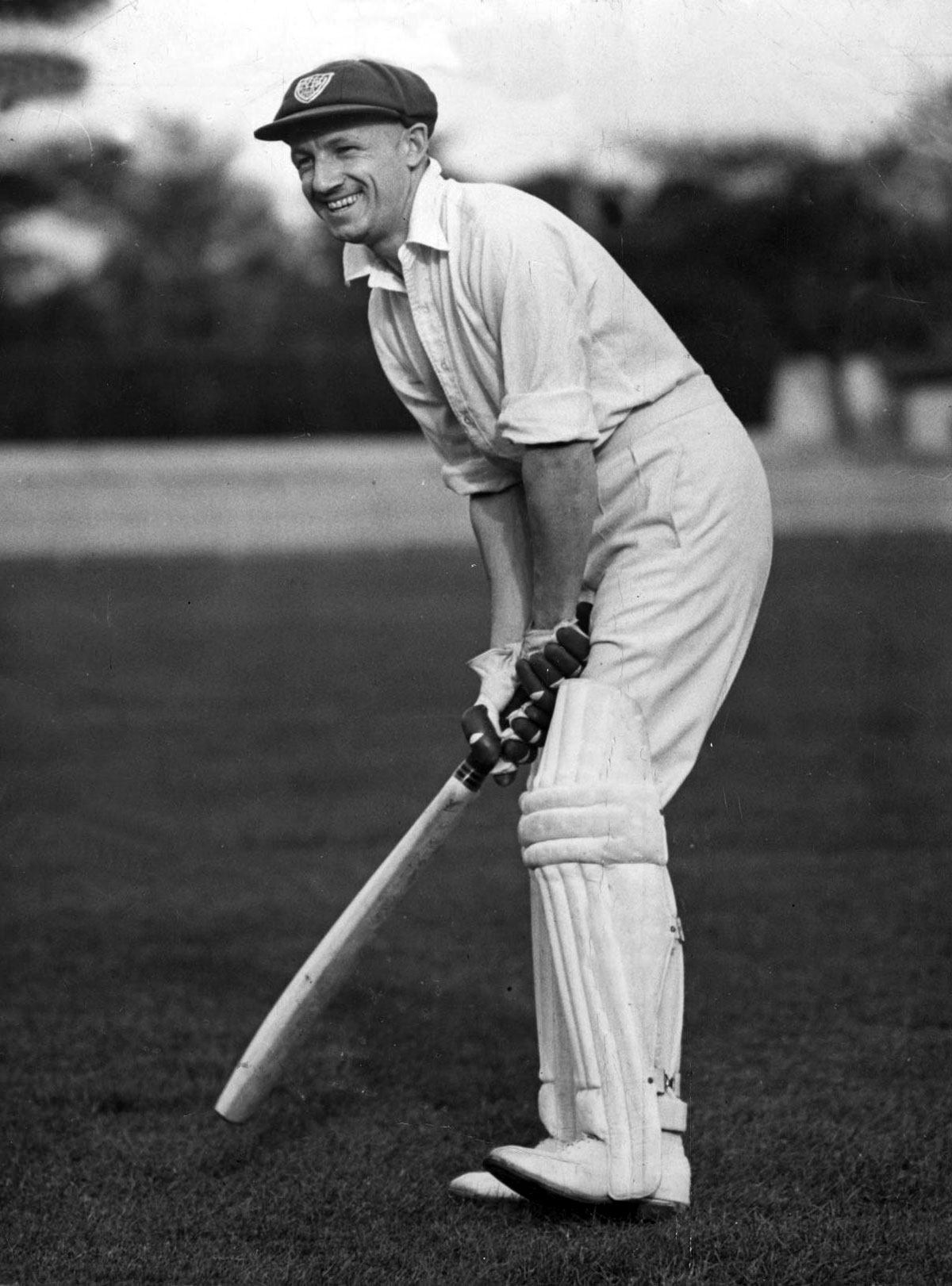

For the first 128 years of Australia's Test history, there was one constant in a boundless sea of technical heterodoxy - great Australian batsmen gently and rhythmically tapped their bats on the ground as the bowler ran in, and kept their bats grounded until around the time the bowler jumped into his delivery stride.

Every permanent member of the top seven (Matthew Hayden, Michael Slater/Justin Langer, Ricky Ponting, Mark Waugh, Steve Waugh, Damien Martyn and Adam Gilchrist) of Australia's victorious 2001 Ashes team - the last to win an Ashes series on English soil - adhered to this method.

Mike Hussey was not a member of that top seven. In the English summer of 2001, Hussey was a 26-year-old Western Australian opening batsman who had never played for Australia at the senior level. In the preceding Australian summer, he had averaged 30.25 in first-class cricket, passing 50 only twice in 21 innings. In the seemingly ever-growing queue of applicants for a spot in the Test line-up, he was, at a conservative estimate, behind Slater, Simon Katich, Darren Lehmann, Brad Hodge, Martin Love, Matthew Elliott, Jimmy Maher, Greg Blewett and Jamie Cox.

As a kid acting out his dream of playing for Australia in backyard games with his younger brother David in the beachside Perth suburb of Mullaloo in the '80s, Hussey tapped his bat and kept it down because, as he revealed to the Cricket Monthly, all the guys he watched batting for Australia, "likeGreg Chappell" and his "hero", Allan Border, did so. The thought of holding his bat up like a baseballer never occurred to him as a kid; none of the Australian Test batsmen he watched and admired did that.

When Hussey scored his solitary first-class hundred of an otherwise dismal summer in March 2001, he was still tapping his bat and keeping it down. But not long thereafter, he realised he had a problem that he would have to rectify if he was to realise his dream of playing for Australia - his bat-tap was causing his head to "fall over too much towards the off side and so… was having trouble hitting the balls off his pads and getting LB". Hussey is five foot ten inches tall and has "quite long legs". He "tried batting with a long blade bat, just to try and keep myself a little more upright and keep my weight more upright, but every time I leant over to tap the bat it took my head over [towards the off side] and I had bad balance".

The pioneer: Mike Hussey's success with holding the bat up in the stance kicked off a revolution in Australian cricket © AFP

Some time after that middling season - he can't remember exactly when - Hussey did something momentous, something that - according to photographic and video evidence compiled by Dean Plunkett, the WACA's Performance Analysis Coordinator - no great Australian Test or Sheffield Shield batsman before him had done: he got rid of his bat-tap and started holding his bat up above knee level as the bowler ran in to bowl. Since his bat-tap was causing his head to fall over, he reasoned that removing it and "standing upright" would enable him to get his head into the best balanced position and "access the straight balls a bit better".

Once he went bat-up, Hussey was unstoppable. He made his one-day international debut in February 2004 and his Test debut in November 2005. After his first 20 Tests, the only batsman he could statistically be compared with was Donald Bradman - he was averaging 84.80.

Hussey retired from Test cricket in January 2013 - with 6235 runs and 19 hundreds, at an average of 51.52 - as the first great Australian Test batsman to use a bat-up technique.

He won't be the last.

Steven Smith uses a bat-up technique. When Australia won a fifth World Cup earlier this year, five batsmen - Smith, Aaron Finch, Shane Watson, Glenn Maxwell and James Faulkner - in Australia's top seven used bat-up. (A sixth member of that top seven, Michael Clarke, could be argued to have had a bat-up technique by that very late stage of his illustrious career, having been bat-down for most of it.)

The significant, and growing, proportion of Australian batsmen who have started holding their bats up like baseballers over the past decade has been, to borrow a phrase from WG Grace, one of those "silent revolutions transforming cricket". Chappell certainly believes so. He said that it's "a revolution that is changing batting like it's never changed before in the history of the game".

Ed Cowan grew up in Sydney, with a poster of Ricky Ponting on his bedroom wall, as a naturally attacking, free-flowing batsman who destroyed bowling attacks and once, according to the renowned junior coach Trent Woodhill, scored 199 off 34 overs in an Under-21 game.

Greg Chappell, one in a long line of bat-down Australian batsmen, believes the traditional method is more efficient since it helps synchronise hand and foot movement © Getty Images

Cowan said he "had always been a very strong back-foot player" and had pulled and hooked the quicks fluently at first-grade level. But, he explained, "when you hit first-class cricket you go from facing guys bowling 125 k's an hour and wickets that don't tend to bounce above your belly button in club cricket to [faster, bouncier] first-class wickets", and bowlers averaging 135kph and regularly exceeding 140. In Cowan's first three Shield matches in early 2005, he faced: Shaun Tait (in his fearsome prime), Ryan Harris, Andy Bichel, Ashley Noffke, Steve Magoffin and Brad Williams. Those blokes didn't bowl at 125kph.

The 22-year-old Cowan quickly realised: "I can't [hook and pull fluently] at this level and I need to find a way because it is limiting what I am doing." He looked at what the best batsmen in Australia and the world were doing. What he saw, in the Australian winter of 2005, was: "the best player in the [New South Wales] squad" and "probably the best player of the short ball in Shield cricket at the time", Katich, with his bat up; Jacques Kallis, one of the best batsmen in the world, with his bat up; Kevin Pietersen, a swashbuckling 25-year-old whose maiden Test hundred had just consigned Australia to their first Ashes series defeat in nearly 19 years, with his bat up; and Hussey, who had an ODI average of 123.50 and a strike rate of 94.45 after the first 21 months of his international career, with his bat up.

Thus, Cowan decided to experiment with his bat up to try to give himself "a chance to play" the hook and pull shots against Shield quicks. Like Hussey before him, Cowan made the decision to go bat-up himself and takes full responsibility for it. He had a conversation with Trevor Bayliss, NSW's coach at the time, about his decision. Bayliss, like most of the best coaches in the land, respected the player's decision. He made no attempt to change it, but he did explain the inherently risky nature of any technical change.

Australian cricketers are always looking for a competitive edge. Their "Darwinian first-class competition", in the words of historian Gideon Haigh, demands it. In light of that and what Haigh calls the "Australian tradition of autodidactism", it was inevitable that once some batsmen, especially a prominent Australian, started dominating at Test level with a bat-up technique, young Australians would give it a go. As Cowan explained: "You can't stop searching for improvement and I think that's player-driven because… players want to perform." For example, "I don't think Steve Smith liked getting out caught in the slips consistently [when he first came into the Test XI in 2010]", therefore, he worked his tail off and rectified that problem by, among other things, adopting a bat-up set-up in around May 2013.

Ian "Mad Dog" Callen played one Test for Australia against India at the Adelaide Oval in 1978, taking 6 for 191 - including the prize wicket of Sunil Gavaskar - to help Bob Simpson's Packer-depleted Australian side win the Test and clinch the five-match series 3-2.

Up or down? Should kids be allowed to develop their own rhythms? © Getty Images

Callen now lives on a property named Kookaburra, near the small Victorian country town of Tarrawarra with his wife, Susan. He greets me with a warm grin inside the two-storey wooden barn, nestled at the bottom of a grassy hill, where he spends his days hand-making cricket bats from his own Australian-grown English willow and training Australian bat-makers in the ancient craft. He takes a seat at the dining table, directly underneath his framed Australian team blazer from the 1977-78 tour of the West Indies, and highlights two technological reasons why the bat-up method has risen in popularity in Australia over the course of the last decade: helmets and bats.

Firstly, the more upright bat-up batsman presents a bigger target for the fast bowler with a good bouncer than the classical, bat-down batsman who is tapping his bat (and therefore at least slightly crouched, on his toes, at the ready, like a boxer). Thus, in the pre- and early-helmet era, the greater likelihood of being struck by a bouncer dissuaded batsmen from going bat-up. However, by the mid-2000s, advancements in helmet technology had greatly reduced the risk of serious injury.

Secondly, Callen found, through systematic testing, that the quality of the sweet spot on a good English willow bat has not changed much, if at all, over the last century - if you drop a ball onto the sweet spot of a 1930s bat, it will bounce as high as one dropped onto the sweet spot of a current-day bat. But the size of the sweet spot has increased exponentially. Therefore, today's batsmen have a much greater margin for error than batsmen in the 1930s or even the 1970s.

Proponents of the bat-down method, such as Chappell, who is now Cricket Australia's National Talent Manager, believe that it enables a batsman to more easily synchronise his hand and foot movement, thereby making it easier for him to get into "a more optimal position" to play the shot that he has imagined, "at the correct time", which in turn enables him to consistently hit "the ball in the middle of the sweet spot". There is obviously less need for him to do that if the sweet spot on his bat is much larger. According to Chappell, bat-up is a "less efficient" method of batting and "it's probably the improvement in the bats that has allowed these [less efficient] methods to prosper, because the mishit goes better than it's ever gone before, so batsmen are probably not getting the feedback… that these methods are less efficient than methods that have been used before".

Firstly, the more upright bat-up batsman presents a bigger target for the fast bowler with a good bouncer than the classical, bat-down batsman who is tapping his bat (and therefore at least slightly crouched, on his toes, at the ready, like a boxer). Thus, in the pre- and early-helmet era, the greater likelihood of being struck by a bouncer dissuaded batsmen from going bat-up. However, by the mid-2000s, advancements in helmet technology had greatly reduced the risk of serious injury.

Secondly, Callen found, through systematic testing, that the quality of the sweet spot on a good English willow bat has not changed much, if at all, over the last century - if you drop a ball onto the sweet spot of a 1930s bat, it will bounce as high as one dropped onto the sweet spot of a current-day bat. But the size of the sweet spot has increased exponentially. Therefore, today's batsmen have a much greater margin for error than batsmen in the 1930s or even the 1970s.

Proponents of the bat-down method, such as Chappell, who is now Cricket Australia's National Talent Manager, believe that it enables a batsman to more easily synchronise his hand and foot movement, thereby making it easier for him to get into "a more optimal position" to play the shot that he has imagined, "at the correct time", which in turn enables him to consistently hit "the ball in the middle of the sweet spot". There is obviously less need for him to do that if the sweet spot on his bat is much larger. According to Chappell, bat-up is a "less efficient" method of batting and "it's probably the improvement in the bats that has allowed these [less efficient] methods to prosper, because the mishit goes better than it's ever gone before, so batsmen are probably not getting the feedback… that these methods are less efficient than methods that have been used before".

Graham Gooch was one of the early proponents of the bat-up method, which worked in English conditions © PA Photos

Chappell provides another reason why bat-up has become so popular: "Young batsmen using bats that are too heavy for them find it very difficult from the bat-down position because it's really hard to overcome inertia, to get started, so they feel that they need to get the bat up early." Justin Langer concurs: "When I was a kid, Kenny Meuleman used to make me use a two-pound-five or -six bat, it was so light. You look at some of these kids, they have got these big, heavy bats, it is a lot harder to pick it up and get rhythm". Langer reveals that up until around 2001 he "was [successfully] playing Test cricket and Shield cricket using two-pound-five or -six bats". Bradman, writing over half a century ago in The Art of Cricket, observed that "a good serviceable weight is about 2 lb. 4 ozs". Nowadays, the national chain of cricket stores that bears Greg Chappell's name doesn't even stock two-pound-five bats for sale!

Two other factors may have contributed to the rise of bat-up over the last decade. Cowan astutely points out that from "six, seven years ago, right until maybe two years ago, Shield wickets were very sporting and so people discovered that [bat-up] helped their game [in those conditions]".

It makes sense that in those green, English-style conditions, Australian batsmen would experiment with, and ultimately adopt, a technique that had been popularised by two successful English batsmen, Tony Greig and Graham Gooch. A bat-up technique helps a batsman achieve a basic level of competence in those conditions - because the bat is already up, the batsman can make a late decision to play or leave the ball, thereby accounting for late lateral movement. But the empirical evidence suggests that it may also hinder a batsman's ability to achieve mastery in them.

From 1989 to 2001, when Australian Test teams touring England featured batting line-ups composed entirely of bat-down batsmen (with the notable exception of Geoff Marsh in 1989), Australia comfortably won every Ashes series played in England. Since the mid-2000s, when bat-up batsmen started filtering into the Test XI, Australia have not won a single Ashes series in England. From 1989 to 2001, Australia's regular top six averaged 52.17 per batsman and scored 31 hundreds in 23 Tests. From 2005 to 2015, Australia's regular top six averaged 37.62 per batsman and scored 17 hundreds in 20 Tests.

Moreover, Chappell observes: "I've seen more low scores in top-level cricket in recent times than I've seen throughout my life because of that reason - [bat-up] batsmen are not able to change their position." That limitation, he explains, is exposed when the ball seams, swings or turns: see, for example, Australia's 60 at Trent Bridge in 2015, 131 in Hyderabad in 2013, 47 at Newlands in 2011, 98 at the MCG in 2010 and 88 at Headingley in 2010.

Two other factors may have contributed to the rise of bat-up over the last decade. Cowan astutely points out that from "six, seven years ago, right until maybe two years ago, Shield wickets were very sporting and so people discovered that [bat-up] helped their game [in those conditions]".

It makes sense that in those green, English-style conditions, Australian batsmen would experiment with, and ultimately adopt, a technique that had been popularised by two successful English batsmen, Tony Greig and Graham Gooch. A bat-up technique helps a batsman achieve a basic level of competence in those conditions - because the bat is already up, the batsman can make a late decision to play or leave the ball, thereby accounting for late lateral movement. But the empirical evidence suggests that it may also hinder a batsman's ability to achieve mastery in them.

From 1989 to 2001, when Australian Test teams touring England featured batting line-ups composed entirely of bat-down batsmen (with the notable exception of Geoff Marsh in 1989), Australia comfortably won every Ashes series played in England. Since the mid-2000s, when bat-up batsmen started filtering into the Test XI, Australia have not won a single Ashes series in England. From 1989 to 2001, Australia's regular top six averaged 52.17 per batsman and scored 31 hundreds in 23 Tests. From 2005 to 2015, Australia's regular top six averaged 37.62 per batsman and scored 17 hundreds in 20 Tests.

Moreover, Chappell observes: "I've seen more low scores in top-level cricket in recent times than I've seen throughout my life because of that reason - [bat-up] batsmen are not able to change their position." That limitation, he explains, is exposed when the ball seams, swings or turns: see, for example, Australia's 60 at Trent Bridge in 2015, 131 in Hyderabad in 2013, 47 at Newlands in 2011, 98 at the MCG in 2010 and 88 at Headingley in 2010.

99.94 reasons to go bat-down © Getty Images

One reason commonly - and incorrectly - cited for the rise of bat-up is the influence of elite-level coaches. It has been widely rumoured that Victoria's coaching staff, led by Greg Shipperd(the state's hugely successful head coach from January 2004 to March 2015), pushed batsmen into adopting bat-up. There is no truth to that rumour. What happened was this: Victorian players, starting with their young captain Cameron White in the mid-2000s, made the decision to go bat-up and then ran it by Shipperd and his coaching staff. Shipperd said that he and his staff were happy to respect the player's decision. "If that's the way you want to go, well, we'll coach around that as your preferred model."

Peter Handscomb - the 24-year-old Victoria batsman-keeper, one of the rising stars of Australian cricket - said that his original decision to start holding his bat up was made in around 2006-07 at the Victorian U-17s carnival at the suggestion of a coach. Handscomb was also "definitely" influenced by the success of batsmen such as Hussey, Kallis and Pietersen, who "were making runs and making it look easier with a bat-up approach".

For Handscomb and many other batsmen of the T20 generation, the bat-up method helps them to play "new shots in the game that weren't there 20 or 30-odd years ago… like reverse sweep, lap sweep, lap shot, basically anything reverse. If you have got your bat on the ground when the ball is released, then to get your bat up and then change and… try and hit the ball, it can almost be too long."

If anyone in Australian cricket has seen it all, it's 40-year-old Brad Hodge. The compact, classical batsman made his debut for Victoria as an 18-year-old in October 1993. And he is still playing - very successfully - all around the world as a T20 freelancer, in addition to working as an assistant coach with Adelaide Strikers. He is bat-down and has always been so, because that is what works for him, but cheerfully acknowledges that bat-up works for other batsmen such as Chris Gayle.

Many coaches fear that the proliferation of bat-up batsmen in the country could endanger the Australian style of aggressive, free-flowing batting © Getty Images

Hodge underlined a benefit of bat-down that Chappell mentioned too - "the feeling of your hands and the rest of your body moving through the ball". By contrast, the bat-up method can make a batsman more "robotic" - as he "rigidly pushes at the ball" - and make him lose that natural "feeling".

Langer, now the highly successful coach of Western Australia and Perth Scorchers, uses a similar word to describe the bat-up method: mechanical. "What often happens when you hold the bat up is that you [have] just got one plane to come down, so you are really stopping the ball, rather than having nice rhythm throughout the delivery". The problem with many mediocre bat-up batsmen is that they stand still and stiff in their stance, with their wrists fully cocked and their bat locked-in at the top of its bat-swing. This means that, like a marble statue of a batsman at the top of his backswing, they often limit themselves to one pre-selected swing plane.

The obvious strength of bat-up, as Cowan observes, is that it allows batsmen to "get a pretty regular [bat-swing]" that is "easy to replicate". But that strength is also the method's greatest flaw. Batting - in the words of two of Australia's greatest batsmen, Bradman and Chappell - is an "art", not a science. Picking the bat up from a neutral, bat-down position allows a batsman to wield his bat like an artist wields his paintbrush on a blank canvas - he can literally do anything with it, as he has an almost infinite variety of swing planes to choose from - whereas the rigid, bat-up batsman, with only a limited number of pre-selected swing planes available to him, often wields his bat like a robot on a factory assembly line.

Moreover, Hodge points out that the bat-down batsman's act of picking his bat up off the ground provides him with "fluid momentum" and natural power. That is particularly beneficial for a batsman like him with "a small stature" who cannot use brute force to muscle the ball over the rope. As his hands pick his bat up off the ground, and his feet move - in sync with his hands - out to the ball, he achieves what Langer lyrically describes as "that beautiful free-flowing fling" as the ball pings off the middle of his bat's sweet spot. This, according to proponents of bat-down, is the method's primary benefit. Chappell calls it "synchronisation". Langer calls it "having good footwork patterns" and "being relaxed at the crease". In the revised 1984 edition of The Art of Cricket, Bradman referred to it as the batsman's "coordination" of "the movements of his bat and feet", before swiftly declaring that he is "an opponent of the [bat-up] method".

Watch any successful bat-up batsman closely at the approximate point of release and one immediately notices that he employs a range of countermeasures to ameliorate the flaws of the bat-up method by effectively imitating the actions of a bat-down batsman. Langer highlights the "very loose" arms, "like a hose in a swimming pool", of the batsmen he admires who have successfully gone bat-up - Steven Smith, Hashim Amla, Katich and Phillip Hughes ("magnificent player he was, a beautiful player") - but concludes that, in his opinion, "the best way to get that relaxation in your shoulders and in your arms is to tap your bat". Chappell concurs and adds that by tapping his bat "subconsciously, the batsman is acting in time with the bowler's rhythm… getting into rhythm with the bowler… is a really important part of batting".

Australia's top seven in the 1990s and early 2000s all faced the bowler from neutral, bat-down positions, which allowed them to choose from a variety of swing planes © Getty Images

Other common countermeasures employed by bat-up batsmen include: wrists that are not cocked (Smith and Maxwell), bent knees (Smith and Handscomb), rocking hands down and up (Joe Root), and a preliminary bat-wiggle (Handscomb and Ben Stokes). Handscomb agrees to an extent with the argument that bat-up can adversely affect balance and synchronisation, but says:

"… there are ways to combat that and you can have your bat up and still be very, very, very balanced… if you watch a lot of batsmen that have bat up, just as the ball's released, there's always a little pre-movement or just something that changes it up and gets them into a strong position. For example, my bat's up but as the ball's coming down my bat goes back down and then back up again, so it's almost as if I've just picked it up off the ground."

Thus, it seems that in order for the bat-up method to work, the batsman must implement a range of countermeasures whose purpose is to imitate a bat-down batsman. That, essentially, is the point that Chappell is making when he describes bat-down as "the most efficient method".

In recent times, seasoned Australian batsmen, such as Cowan and Adam Voges, have substantially improved their performances by reverting to bat-down. Chappell and Langer both played a part in persuading Cowan to make the change. Langer was rather more blunt with his mate "Vogey", a man he respects and admires. "He'd been playing county cricket and he was batting like Graham Gooch with his left foot pointing down the wicket and I said, 'Mate, what the f*** are you doing?' He goes: 'Aw, I'll be in trouble [if I change now].' I said: 'Mate, nah, I'm not throwing you one more ball, I'm coach of Western Australia now, please start getting your stance right, start tapping again, mate, just get natural again.' Well, the rest is history."

Voges, after taking a season to bed down the technical change, put together two outstanding Shield summers, averaging 54.92and 104.46, to earn his Test cap at the age of 35. He proceeded to score a match-winning century on debut and was recently named the vice-captain of Australia for the eventually postponed Test tour of Bangladesh.

Two schools of thought have arisen in Australia in response to the spread of bat-up. The first, the freedom school, has no objection to kids experimenting with bat-up - but does not actively tell kids to go bat-up - because, as Shipperd explains, coaches like him believe that the decision belongs to the individual batsman. "We coach around that [decision], as opposed to fighting [it]." Shipperd and Woodhill - Steven Smith's highly respected junior coach, who currently works as David Warner's personal batting coach - belong to this school. Woodhill cautions that broad anti-bat-up pronouncements could hinder young batsmen establishing their own technique and we could "miss out on the more unusual superstar like a Steven Smith".

Comedown: Adam Voges returned to the bat-down method in 2012, and his subsequent prolific domestic seasons won him a Test cap at the age of 35 © Getty Images

The second school of thought, the Bradman-Chappell school, believes that the bat-up method, if used by kids, threatens the ability to produce truly Australian batsmen - that is, outstanding, free-flowing artists who destroy all types of bowling in all conditions - which, in turn, would threaten the ability to continue to play a distinctly Australian style of cricket - aggressive, attacking and winning. Accordingly, Chappell believes that Cricket Australia should adopt a "coherent policy" which explains to kids (and coaches) why bat-down is the most efficient way to learn to bat so that they have the opportunity - that "they've not been given in recent times" - "to experiment with the bat down".

Langer broadly agrees with Chappell's policy proposal. Ultimately the empirical evidence in favour of that policy is simply too persuasive. Plunkett compiled photographs and videos of Australia's top 15 Test and top 15 Shield run scorers at the approximate point of the bowler's release. Of those 29 great Australian batsmen (Langer appears on both lists), only two - Hussey and Chris Rogers - were bat-up.

It must be emphasised that the batsmen are categorised by reference to their position at the approximate point of the bowler's release. The great Australian batsmen did not all lift their bats at exactly the same point in time - there is, and has always been, a range of temporal lift points. At one end of the spectrum are Steve Waugh and Greg Chappell, who kept their bats grounded until just before the bowler released the ball. At the other end are Border and Michael Clarke, who lifted their bats relatively early - roughly when the fast bowlers jumped into their delivery stride. Border and Clarke are still categorised as bat-down, bat-tappers in Plunkett's data - because by tapping their bats as the bowler ran in to bowl and only lifting their bats at the approximate point of release, they accessed the substantive benefits of the bat-down method.

Cowan describes Plunkett's empirical evidence as compelling and acknowledges that "that's what brought me back to where I am now", which is bat-down, like he was as a kid. As Chappell points out, even those batsmen who have successfully gone bat-up as adults - for example, Hussey, Handscomb, Katich, Steven Smith, Kallis and AB de Villiers - learned the game as kids with their bats down.

Former Victoria coach Greg Shipperd was happy to allow his players to experiment with their batting stances, coaching around it, rather than fighting it © Getty Images