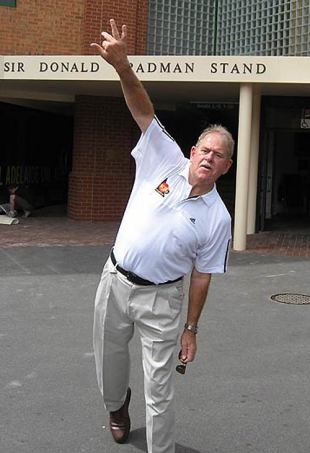

Michael Moore says of Capitalism: A Love Story, 'I want audiences to get off the bench and become active.' Photograph: Kevork Djansezian/AP/PA Photos

Michael Moore has been accused of many things. Mendacity. Manipulation. Rampant egotism. Bullying a frail old man with Alzheimer's. And that is by people who generally agree with his views. His latest film Capitalism: A Love Story is already out in the US when we meet. He comes storming down the hotel corridor, predictably unkempt in ragged jeans that have the unusual quality of appearing both too large and too small at the same time.

I wasn't sure what to expect. Arrogance, perhaps. Cynicism. But he begins to schmooze while he's still some distance away, shouting he feels he knows me. A few months ago one of Moore's producers interviewed me for the film. I was cut from the finished version but Moore says he watched my every word.

Settled on a couch I ask why he hasn't managed to persuade the downtrodden, uninsured, exploited masses to revolt. "My films don't have instant impact because they're dense with ideas that people have not thought about," he says. "It takes a while for the American public to wrap its head around some of the things I'm saying. Twenty years ago I told them that General Motors was going to collapse and take a lot of towns down with them. I was ridiculed, and GM sent around this packet of information about me, my past writings – pinko! With Bowling for Columbine, I told people that these shootings are going to continue, we've got too many guns, too easy access to the guns. [In Fahrenheit 9/11] I'm telling people that we're not going to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, we've been lied to."

Capitalism: A Love Story seems the natural culmination of all his others, an overarching look at the insidious control of Wall Street and corporate interests over politics and lives. Its timing is exquisite, coming in the wake of the biggest financial collapse in living memory. And once again Moore is bracing himself: as the film drew to a close at its premiere in Los Angeles, he posted a message on Twitter: "The packed house gets up to grab their torches and pitchforks …"

The film is certainly shocking. Early on, Moore sets out the meaning of "Dead Peasants" insurance. It turns out that Wal-Mart, a company with a revenue larger than any other in the world, bets on its workers dying, taking out life insurance policies on its 350,000 shop-floor workers without their knowledge or approval. When one of them dies, Wal-Mart claims on the policy. Not a cent of the payout, which sometimes runs to a $1m (£620,000) or more, goes to the family of the dead worker, often struggling with expensive funeral bills. Wal-Mart keeps the lot. If a worker dies, the company profits.

Wal-Mart is not alone. Moore talks to a woman whose husband died of brain cancer in 2008. He worked at a bank until it fired him because he was sick. But the bank retained a life insurance policy on the unfortunate man and cashed it in for $4.7m (£2.9m) when he died. There were gasps from the audience in a Washington cinema at that.

They came again as Moore focused on the eviction of the foreclosed. The Hacker family of Peoria filmed themselves being chucked out of their home because of skyrocketing mortgage payments. Randy Hacker, gun owner, observes that he can understand why someone might want to shoot up a bank. In a final twist, the eviction squad offers the Hackers cash to clear out their yard.

The Hackers are Republicans. So was the widow of the bank worker. It is the gap, between the ordinary American – Democrat or Republican, middle-class or dirt-poor – and predatory banks and mammoth corporations that Moore has made his target ever since Roger and Me, his first film, set out to expose the damage wreaked by General Motors on his hometown of Flint, Michigan.

"One movie maybe can't make a difference," Moore says. "I'll say, what's the point of this? What do I want [my audiences] to do? Obviously I want them to be engaged in their democracy. I want them to get off the bench and become active."

Last summer something happened that renewed Moore's conviction that his film-making was politically worthwhile. "I'm in the edit room and there's Bill Moyers on the TV interviewing the vice-president of Sigma health insurance. Massive, billion-dollar company. He's sitting there, telling the country that he's quit his job and he wants to come clean. That he and the other health insurance companies got together and pooled their resources to smear me and the film Sicko to try and stop people from going to see it because, as he said, everything Michael Moore said in Sicko was true, and we were afraid this film would be a tipping point.

"I came away from that, with 'Wow, they're

afraid of this movie, they believe it can actually create a revolution.' The idea that cinema can be dangerous is a great idea."

Moore's critics would argue this is his ego speaking. The idea that his film about the failings of the US healthcare system was on the brink of prompting a revolution of any kind looks all the more far-fetched given how the political fight over the issue has panned out. But if Moore's primary intention is to send up a warning flare, to alert Americans to what is going on in their country but not usually reported, he's been pretty successful.

At the end of Capitalism: A Love Story, Moore makes a pronouncement: "Capitalism is an evil, and you cannot regulate evil. You have to eliminate it and replace it with something that is good for all people and that something is democracy." Michael Moore once planned to be a priest. In his youth he was drawn to the Berrigan brothers, a pair of radical priests who pulled anti-Vietnam war stunts such as pouring blood on military service records. In an instructive moment for Moore, the brothers made clear they weren't just protesting against the war, but against religious organisations that kept silent about it.

These days he disagrees with Catholic orthodoxy exactly where you would expect him to – he supports abortion rights and gay marriage – but he credits his Catholic upbringing with instilling in him a sense of social justice, and an activism tinged with theatre that lives on his films.

But what does it mean, to replace capitalism with democracy? He sighs and tries to explain. In the old Soviet bloc, he says, communism was the political system and socialism the economic. But with capitalism, he complains, you get political and economic rolled in to one. Big business buys votes in Congress. Lobbyists write laws. The result is that the US political system is awash in capitalist money that has stripped the system of much of its democratic accountability.

"What I'm asking for is a new economic order," he says. "I don't know how to construct that. I'm not an economist. All I ask is that

it have two organising principles. Number one, that the economy is run democratically. In other words, the people have a say in how its run, not just the 1%. And number two, that it has an ethical and moral core to it. That nothing is done without considering the ethical nature, no business decision is made without first asking the question, is this for the common good?"

These days Moore, the son of a Flint car worker, lives in the smalltown surrounds of Traverse City with his wife Kathleen Glynn and stepdaughter Natalie, a four-hour drive and a world away from where he came from. But Traverse City, which is on Lake Michigan, has endured its own decline. Walking along the restored foreshore, a sign says that the city was once a major lumber exporter. Now it is known as the "Cherry Capital" of America.

"When I first got here the theatre was boarded up," says Moore. "It was a mess. I said, look, let me reopen this theatre, I'll create a non-profit. It has brought, like, half a million people downtown in the first two years. If they're downtown they go out to dinner, they go to the bookstore. It livens everything up. Stores open. Now there's no plywood on any windows." This, says Moore, has made him something of a local hero even in a town that votes Republican.

"The county voted for McCain and for Bush twice. But not a day goes by when a Republican here doesn't stop me on the street and shake my hand and thank me. Me, the pariah!"

There are conservatives who get Moore's message, particularly families such as the Hackers who have been betrayed by the system they thought was working for them. But identifying their suffering, and even the cause of their problems, is very different from persuading them that capitalism is evil, although they might just buy in to what Moore says is the core message of his latest film – "that Wall Street and the banks are truly the enemy, and we need to tie that beast down and quick".

His enemies in the rightwing media will be doing everything they can to ensure this doesn't happen, portraying him as a propagandist. And even some of his supporters say he is too willing to leave out inconvenient facts. But there's no denying some very powerful truths in Capitalism, one of which is that it didn't need to be this way in America.

Moore has dug out of a South Carolina archive a piece of film buried away 66 years ago because it threatened to rock the foundations of the capitalist system as Americans now know it.

President Franklin D Roosevelt was ailing. Too ill to make his 1944 state of the nation address to Congress, he instead broadcast it by radio. But at one point he called in the cameras, and set out his vision of a new America he knew he would not live to see.

Roosevelt proposed a second bill of rights to guarantee every American a job with a living wage, a decent home, medical care, protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness and unemployment, and, perhaps most dangerously for big business, freedom from unfair monopolies. He said that "true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence".

The film was quickly locked away.

"The next week on the newsreels – and we've gone back and researched this – they didn't run that," said Moore. "They talked about other parts of his speech, the war. Nothing about this. The footage became lost. When we called the Roosevelt presidential library and asked them about it they said it wasn't filmed. His own family told us it wasn't filmed." Moore's team scoured the country without luck until they were given a tip about a collector connected to the university of South Carolina.

The university didn't have anything archived under FDR's speeches that fitted, but there were a couple of boxes from that week in 1944.

"We pop it in. It was all there. We had tears in our eyes watching it. For 65 years not a single American saw that speech, not one. I decided right then that we're going to fulfil Roosevelt's wishes that the American people see him saying this. Of all the things in the film, probably I feel most privileged that I get to share this. I get to give him his stage." It's a powerful moment not only because it offers an alternative view of American values rarely spoken of today – almost all of which would be condemned as rampant socialism – but also an interesting reference point with which to compare the more restrained ambitions of the Obama administration.

It is hard to imagine any circumstances in which Obama could put forward such an agenda, I suggest. Moore disagrees.

"He could make that speech."

And survive politically?

"He has told people he's going to operate these four years not with an eye on getting re-elected but on getting things done. I have been very happy for the last year. We came out of eight dark years and his election was – what's the word? – the

relief I felt that night, I've been filled with hope since then. Now my patience is running a bit thin. He hasn't taken the reins and said: I'm in charge here, this is what we're doing. Do it. I can understand he's afraid but he's gotta do it."

Dude, where's my country? Michael Moore's America

"A thief-in-chief … a drunk, a possible felon, an unconvicted deserter and a crybaby"

On George Bush, 2001 "I say stupid white men are always the problem. That's never going to change"

After 9/11, in response to his publisher's pleas that he go easy on Bush "It was pretty much like any other morning in America. The farmer did his chores. The milkman made his deliveries. The president bombed another country whose name we couldn't pronounce"

In Bowling for Columbine, 2002 "Back home we call it fuck-you money, OK? What that means is, the distributor of the film can't ever say to me, 'Don't you dare say this in the interview' or 'You better change that in the movie because if you don't, you're not going to get another movie deal.' Because I already have my home and my family taken care of, and enough money from this film and book to make the next film, I'm able to say, 'Fuck you.' No one in authority can hold money over me to get me to conform."

2002 "There is a country I would like to tell you about. It is a country like no other on the planet. Many of you, I am certain, would love to live there. It is a very, very liberal, liberated, and free-thinking country. Its people hate the thought of going to war. The vast majority of its men have never served in any kind of military and they aren't rushing to sign up now … The majority of its residents strongly believe in equal rights for women and oppose any attempt by the government or religious groups who would seek to control their reproductive organs ..."

2003 "There's a gullible side to the American people. Religion is the best device used to mislead them … and we have disastrous media."

2003 "I would like to apologise for referring to George W Bush as a 'deserter'. What I meant to say is that George W Bush is a deserter, an election thief, a drunk-driver, a WMD liar and a functional illiterate. And he poops his pants."

2004 "Halliburton is not a 'company' doing business in Iraq. It is a

war profiteer, bilking millions from the pockets of average Americans. In past wars they would have been arrested – or worse."

2004 Research by Isabelle Chevallot Capitalism: A Love Story is released on 26 February