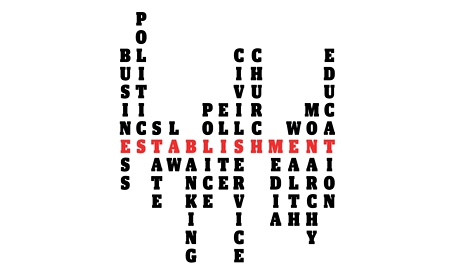

‘I had a fairly normal couple of days before the inspectors arrived: I planned my lessons and went home at a normal time because I was meeting my mate Rob for a run.’ Photograph: Peter Morrison/AP

The Secret Teacher

I have a certain sympathy with the concept of accountability: we all want to know if our local school is any good and that our taxpayer contributions are spent effectively. But the way this straightforward desire has manifested itself in Ofsted– and the way some managers in schools have chosen (and it is a choice) to implement the inspectorate’s criteria – has turned the entire process into a pointless, stressful, tick-box exercise.

I’ve been teaching in secondary schools for 16 years and have just been through my fifth Ofsted inspection. I never used to think much about inspections, but now they’re seen as a life-altering, career-defining Armageddon. It’s hard to identify a tipping point that led us to the current state of affairs, where colleagues try to redefine teaching and work idiotic hours to invent lessons that achieve the impossible. I saw one teacher sob uncontrollably in the staffroom because he’d been up until 4 am preparing a lesson which wasn’t inspected. A colleague and I tried to console him, but finding words of support did not come easily. I found myself angry and frustrated that educated adults and experienced professionals were being reduced to tears.

Driving home that day, I was determined this wouldn’t be me. I’ve no problem with being held accountable for my students’ achievements, but if I wanted to keep doing the job I love, I needed to find a new way of dealing with it.

So now I treat Ofsted inspections as a purposeless farce and never ask for feedback on my lessons. I care about my students’ outcomes great deal, but making judgments about a lesson based on a spurious grid of phrases that defy consistent interpretation has become so lamentably futile there is nothing left to do other than laugh.

At my last school, I had a lesson inspection conducted by two assistant headteachers during a mocksted. The lesson was graded as “good” so I asked them what I could do to make it “outstanding”. They looked blank and eventually suggested I should have spent a bit longer during a discussion section of the lesson. I pointed out that this would have reduced the time for plenary reflection – the latest targeted initiative – and they agreed. I never did get a clear answer on whether it was even possible to make the lesson “outstanding”.

Fast forward a week and the headteacher dropped in on me unannounced. By pure chance I was teaching the same lesson (with some minor tweaks) to a parallel year group of almost identical ability range. The head deemed my lesson “inadequate”. I pointed out that her two assistant heads, one of whom is in charge of teaching and learning, thought the same lesson was “good” – her reponse was to dispute whether the lesson was the same.

I could feel a sense of overwhelming frustration building up. I pointed out at some length that my GCSE and A-level results had been above the school average and that student uptake and retention had grown since my appointment, and then asked to be observed again to prove I know what I’m doing. She never came.

My current school was inspected by Ofsted late last year. As the meeting was called to tell us of the impending visit, I immediately reflected on how my previous experiences could help me. I decided that while I can’t choose when or if I will be inspected – nor what the outcome will be – I can choose how I respond to it.

As expected, senior management went into overdrive with last-minute initiatives and tick-box exercises. But I had a fairly normal couple of days: I planned my lessons normally and went home at a normal time because I was meeting my mate Rob for a run. I told my department what I was doing and that we’d all be best prepared for the next few days with a decent night’s sleep. I said that under no circumstances should they change their evening plans: I trusted their judgement about how best to plan their lessons, and that we would deal with the outcomes – good or bad – afterwards. I’ve no idea what senior management thought, but I assured my department we weren’t going to be sacked for leaving before 9pm. Sure enough, the next day an inspector wandered in to see my year 11s. The lesson passed without hitch, and he invited me to see him at the end of the day for feedback.

I didn’t go. What’s the point? He wasn’t a specialist in my subject and he was only going to tell me his interpretation of a grid of lesson descriptors that has changed virtually every year for the last decade. As far as I know, no-one has been fired or had their pay reduced directly as a result of one Ofsted lesson inspection alone. Some colleagues thought I was mad or disrespectful, but if the inspector had a problem with my teaching and results, he could have found me and said what was wrong and why. Any good teacher knows that students’ progress is neither linear nor predictable, or consistent across subjects and time. Any good teacher also knows that building skills of resilience, humility, determination, awareness, ambition and curiosity cannot be measured by a grid.

I’m not a maverick. Maybe other teachers are worried about the consequences of taking a different approach because some school managers continually “motivate” staff by waving a big Ofsted stick.

But it’s my choice. I’m going to care less about Ofsted and put my energy into my students. I love my job and I don’t want to waste energy resenting certain aspects of what it has become. I know at times this will be easier said than done, but to continue doing what I do best, I need to make sure I keep what is lacking in the current climate – perspective.

The Secret Teacher

I have a certain sympathy with the concept of accountability: we all want to know if our local school is any good and that our taxpayer contributions are spent effectively. But the way this straightforward desire has manifested itself in Ofsted– and the way some managers in schools have chosen (and it is a choice) to implement the inspectorate’s criteria – has turned the entire process into a pointless, stressful, tick-box exercise.

I’ve been teaching in secondary schools for 16 years and have just been through my fifth Ofsted inspection. I never used to think much about inspections, but now they’re seen as a life-altering, career-defining Armageddon. It’s hard to identify a tipping point that led us to the current state of affairs, where colleagues try to redefine teaching and work idiotic hours to invent lessons that achieve the impossible. I saw one teacher sob uncontrollably in the staffroom because he’d been up until 4 am preparing a lesson which wasn’t inspected. A colleague and I tried to console him, but finding words of support did not come easily. I found myself angry and frustrated that educated adults and experienced professionals were being reduced to tears.

Driving home that day, I was determined this wouldn’t be me. I’ve no problem with being held accountable for my students’ achievements, but if I wanted to keep doing the job I love, I needed to find a new way of dealing with it.

So now I treat Ofsted inspections as a purposeless farce and never ask for feedback on my lessons. I care about my students’ outcomes great deal, but making judgments about a lesson based on a spurious grid of phrases that defy consistent interpretation has become so lamentably futile there is nothing left to do other than laugh.

At my last school, I had a lesson inspection conducted by two assistant headteachers during a mocksted. The lesson was graded as “good” so I asked them what I could do to make it “outstanding”. They looked blank and eventually suggested I should have spent a bit longer during a discussion section of the lesson. I pointed out that this would have reduced the time for plenary reflection – the latest targeted initiative – and they agreed. I never did get a clear answer on whether it was even possible to make the lesson “outstanding”.

Fast forward a week and the headteacher dropped in on me unannounced. By pure chance I was teaching the same lesson (with some minor tweaks) to a parallel year group of almost identical ability range. The head deemed my lesson “inadequate”. I pointed out that her two assistant heads, one of whom is in charge of teaching and learning, thought the same lesson was “good” – her reponse was to dispute whether the lesson was the same.

I could feel a sense of overwhelming frustration building up. I pointed out at some length that my GCSE and A-level results had been above the school average and that student uptake and retention had grown since my appointment, and then asked to be observed again to prove I know what I’m doing. She never came.

My current school was inspected by Ofsted late last year. As the meeting was called to tell us of the impending visit, I immediately reflected on how my previous experiences could help me. I decided that while I can’t choose when or if I will be inspected – nor what the outcome will be – I can choose how I respond to it.

As expected, senior management went into overdrive with last-minute initiatives and tick-box exercises. But I had a fairly normal couple of days: I planned my lessons normally and went home at a normal time because I was meeting my mate Rob for a run. I told my department what I was doing and that we’d all be best prepared for the next few days with a decent night’s sleep. I said that under no circumstances should they change their evening plans: I trusted their judgement about how best to plan their lessons, and that we would deal with the outcomes – good or bad – afterwards. I’ve no idea what senior management thought, but I assured my department we weren’t going to be sacked for leaving before 9pm. Sure enough, the next day an inspector wandered in to see my year 11s. The lesson passed without hitch, and he invited me to see him at the end of the day for feedback.

I didn’t go. What’s the point? He wasn’t a specialist in my subject and he was only going to tell me his interpretation of a grid of lesson descriptors that has changed virtually every year for the last decade. As far as I know, no-one has been fired or had their pay reduced directly as a result of one Ofsted lesson inspection alone. Some colleagues thought I was mad or disrespectful, but if the inspector had a problem with my teaching and results, he could have found me and said what was wrong and why. Any good teacher knows that students’ progress is neither linear nor predictable, or consistent across subjects and time. Any good teacher also knows that building skills of resilience, humility, determination, awareness, ambition and curiosity cannot be measured by a grid.

I’m not a maverick. Maybe other teachers are worried about the consequences of taking a different approach because some school managers continually “motivate” staff by waving a big Ofsted stick.

But it’s my choice. I’m going to care less about Ofsted and put my energy into my students. I love my job and I don’t want to waste energy resenting certain aspects of what it has become. I know at times this will be easier said than done, but to continue doing what I do best, I need to make sure I keep what is lacking in the current climate – perspective.