Molly Crabapple in Boing Boing

Here's what I've learned.

1. The number one thing that would let more independent artists exists in America is a universal basic income. The number one thing that has a possibility of happening is single payer healthcare. This is because artists are humans who need to eat and live and get medical care, and our country punishes anyone who wants to go freelance and pursue their dream by telling them they might get cancer while uninsured, and then not be able to afford to treat it.

2. Companies are not loyal to you. Please never believe a company has your back. They are amoral by design and will discard you at a moment's notice. Negotiate aggressively, ask other freelancers what they're getting paid, and don't buy into the financial negging of some suit.

3. I've cobbled together many different streams of income, so that if the bottom falls out of one industry, I'm not ruined. My mom worked in packaging design. When computers fundamentally changed the field, she lost all her work. I learned from this.

4. Very often people who blow up and become famous fast already have some other sort of income, either parental money, spousal money, money saved from another job, or corporate backing behind the scenes. Other times they've actually been working for 10 years and no one noticed until suddenly they passed some threshold. Either way, its good to take a hard look- you'll learn from studying both types of people, and it will keep you from delusional myth-making.

5. I've never had a big break. I've just had tiny cracks in this wall of indifference until finally the wall wasn't there any more

6. Don't be a dick. Be nice to everyone who is also not a dick, help people who don't have the advantages you do, and never succumb to crabs in the barrel infighting.

7. Remember that most people who try to be artists are kind of lazy. Just by busting your ass, you're probably good enough to put yourself forward, so why not try?

8. Rejection is inevitable. Let it hit you hard for a moment, feel the hurt, and then move on.

9. Never trust some Silicon Valley douchebag who's flush with investors' money, but telling creators to post on their platform for free or for potential crumbs of cash. They're just using you to build their own thing, and they'll discard you when they sell the company a few years later.

10. Be a mercenary towards people with money. Be generous and giving to good people without it.

11. Working for free is only worth it if its with fellow artists or grassroots organizations you believe in, and only if they treat your respectfully and you get creative control.

12. Don't ever submit to contests where you have to do new work. They'll just waste your time, and again, only build the profile of the judges and the sponsoring company. Do not believe their lies about “exposure”. There is so much content online that just having your work posted in some massive image gallery is not exposure at all.

13. Don't work for free for rich people. Seriously. Don't don't don't. Even if you can afford to, you're fucking over the labor market for other creators. Haggling hard for money is actually a beneficial act for other freelancers, because it is a fight against the race to the bottom that's happening online.

14. If people love your work, treat them nice as long as they're nice to you.

15. Be massively idealistic about your art, dream big, open your heart and let the blood pour forth. Be utterly cynical about the business around your art.

Finally...

The Internet will not save creators.

Social media will not save us. Companies will not save us. Crowd-funding will not save us. Grants will not save us. Patrons will not save us.

Nothing will save us but ourselves and each other.

Now make some beautiful things.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label creative. Show all posts

Showing posts with label creative. Show all posts

Sunday, 1 January 2017

Friday, 23 December 2016

Friday, 19 August 2016

Creative Visualisation - Your Mind Can Keep You Well

PSI TEK

Did you know that it is only recently that medical doctors have accepted how important the power of the mind is in influencing the immune system of the human body? Many decades passed before these men of science decided to test the proposition that the brain is involved in the optimum functioning of the different body systems. Recent research shows the undeniable connection --the link-- between mind and body, which challenged the long-held medical assumption. A new science called psychoneuroimmunology or PNI, the study of how the mind affects health and bodily functions, has come out of such research.

A psychologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Lean Achterberg, suggests that emotion may form the link between mind and immunity. “Many of the autonomic functions connected with health and disease,” she explains,” are emotionally triggered.”

Exercises which encourage relaxation and mental activities such as creative visualization, positive thinking, and guided imagery produce subtle changes in the emotions which can trigger either a positive or a negative effect on the immune system. This explains why positive imaging techniques have resulted in dramatic healings in people with very serious illnesses, including cancer.

OMNI magazine claims (February, 1989), in a cover article entitled “Mind Exercises That Boost Your Immune System”:

“As far back as the Thirties, Edmund Jacobson found that if you imagine or visualize yourself doing a particular action - say, lifting an object with your right arm - the muscles in that arm show increased electrical activity. Other scientists have found that imagining an object moving across the sky produces more eye movements than visualizing a stationary object.”

One of the most dramatic applications of imagery in coping with illness is the work of Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist in Dallas, Texas. “By combining relaxation with personalized images,” reports OMNI magazine, “he has helped terminal cancer patients reduce the size of their tumors and sometimes experience complete remission of the disease.”

Many of his patients have benefited from this technique. It simply shows how positive visualization can help alleviate - if not totally cure - various diseases including systemic lupus erythomatosus, migraine, chronic back pain, hyperthyroidism, high blood pressure, hyper-acidity, etc.

However, individual differences have to be taken into consideration when discussing each patient’s progress. It’s understandable that individuals have varying abilities to visualize or create mental images clearly; some people will benefit more from positive-imagery techniques than others

Nevertheless, if visualization can help people overcome diseases, it could possibly help healthy individuals keep their immune system in top shape. Says OMNI magazine: “Practicing daily positive-imaging techniques may, like a balanced diet and physical exercise routine, tip the scales of health toward wellness.”

The Simonton process of visualization for cancer

Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist, and his wife, Stephanie Matthews-Simonton, a psychotherapist and counselor specializing in cancer patients, have developed a special visualization or imaging technique for the treatment of cancer which is now popularly known as the Simonton process. Ridiculed at first by the medical profession, the Simonton process is now being used in at least five hospitals across the United States to fight cancer.

The technique itself is the height of simplicity and utilizes the tremendous powers of the mind, specifically its faculty for visualization and imagination, to control cancer. First, the patient is shown what a normal healthy cell looks like. Next, he is asked to imagine a battle going on between the cancer cell and the normal cell. He is asked to visualize a concrete image that will represent the cancer cell and another image of the normal cell. Then he is asked to see the normal cell winning the battle against the cancer cell.

One youngster represented the normal cell as the video game character Pacman and the cancer cell as the “ghosts” (enemies of Pacman), and then he saw Pacman eating up the ghosts until they were all gone.

A housewife saw her cancer cell as dirt and the normal cell as a vacuum cleaner. She visualized the vacuum cleaner swallowing up all the dirt until everything was smooth and clean.

Patients are asked to do this type of visualization three times a day for 15 minutes each time. And the results of the initial experiments in visualization to cure cancer were nothing short of miraculous. Of course, being medical practitioners, Dr. Simonton and his psychologist wife were aware of the placebo effect and spontaneous remission of illness. As long as they were getting good results with the technique, it didn’t seem to matter whether it was placebo or spontaneous remission.

The Simontons also noticed that those who got cured had a distinct personality. They all had a strong will to live and did everything to get well. Those who didn’t succeed had resigned themselves to their fate.

While the Simontons were exploring the motivation of cancer patients, they were also looking into two interesting areas of research at that time: biofeedback and the surveillance theory. Both areas had something to do with the influence of the mind over body processes. Stephanie Simonton explains in her book The Healing Family:

In biofeedback training, an individual is hooked up to a device that feeds back information on his physiological processes. A patient with tachycardia, an irregular heartbeat, might be hooked up to an oscilloscope, which will give a constant visual readout of the heartbeat. The patient watches the monitor while attempting to relax…when he succeeds in slowing his heartbeat through his thinking, he is rewarded immediately by seeing that fact on visual display.

The surveillance theory holds that the immune system does in fact produce ‘killer cells’ which seek out and destroy stray cancer cells many times in our lives, and it is when this system breaks down, that the disease can take hold. When most patients are diagnosed with cancer, surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy are used to destroy as much of the tumor as possible. But once the cancer is reduced, we wondered if the immune system could be reactivated to seek out and destroy the remaining cancer cells.

The Simontons reasoned that since people can learn how to influence their blood flow and heart rate by using their minds, they could also learn to influence their immune system. Later research proved their approach to be valid.

For instance, according to the Time-Life Book The Power of Healing, “chronic stress causes the brain to release into the body a host of hormones that are potent inhibitors of the immune system”. “This may explain why people experience increased rates of infection, cancer, arthritis, and many other ailments after losing a spouse.” Dr. R.W. Berthop and his associates in Australia found that blood samples of bereaved individuals showed a much lower level of lymphocyte activity than was present in the control group’s samples. Lymphocytes are a variety of white blood cells consisting of T cells and B cells, both critical to the action of the immune system. T cells directly attack disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and toxins, and regulate the other parts of the immune system. B cells produce antibodies, which neutralize invaders or mark them for destruction by other agents of the immune system.

The Power of Healing concludes: “The idea that there is a mental element to healing has gained acceptance within the medical establishment in recent years. Many physicians who once discounted the mind’s ability to influence healing are now reconsidering, in the light of new scientific evidence. All these have led some physicians and medical institutions toward a more holistic approach, to treating the body and mind as a unit rather than as two distinct entities. Inherent in this philosophy is the belief that patients must be active participants in the treatment of their illnesses.

Using visualization for minor ailments

Today, many scientific breakthroughs have proven that minor infections and viruses may be healed, or at least lessened in severity by employing mental techniques similar to those used by cancer patients who have successfully shrunk tumors through positive imaging or visualization.

The theory is that creative visualization can create the same physiological changes in the body that a real experience can. For example, if you imagine squeezing a lemon into you mouth, you will most likely salivate, the same way as when a real lemon is actually being squeezed into your mouth. Einstein once declared that, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In the 1985 World Conference on Imaging, reports OMNI magazine (February 1989), registered nurse Carol Fajoni observed that “people who used imagery techniques to heal wounds recovered more quickly than those who did not. In workshops, the same technique has been used by individuals suffering from colds with similar results.” The process has been hailed as a positive breakthrough and is currently being used by more enlightened doctors, according to OMNI magazine.

Visualize that part of your body which is causing the problem. Then erase the negative image and instead picture that organ or part to be healthy. Let's say you have a sinus infection. Just picture your sinus passageways and cavities as beginning to unclog. Or if you have a kidney disorder, imagine a sick-looking kidney metamorphose into a healthier one.

“In trying to envision yourself healthy, you need not view realistic representations of the ailing body part. Instead, imagine a virus as tiny spots on a blackboard that need erasing. Imagine yourself building new, healthy cells or sending cleaning blood to an unhealthy organ or area.”

“If you have a headache, picture your brain as a rough, bumpy road that needs smoothing and proceed to smooth it out. The point is to focus on the area you believe is causing you to feel sick, and to concentrate on visualizing or imaging it to be well. The more clearly and vividly you can do this, the more effective the technique becomes.”

Another method for banishing pain was developed by Russian memory expert, Solomon V. Sherehevskii, as reported by Russian psychologist Professor Luria. To banish pain, such as a headache, Sherehevskii would visualize the pain as having an actual shape, mass and color. Then, when he had a “tangible” image of the pain in his mind, he would visualize or imagine this concrete picture slowly becoming smaller and smaller until it disappeared from his mental vision. The real pain disappears with it. Others have modified this same technique and suggest that you imagine a big bird or eagle taking the concrete image of the pain away. As it flies over the horizon, see it becoming smaller until it disappears from your view. The actual pain will disappear with it.

Of course, the effectiveness of this imaging technique depends on the strength of your desire to improve your health and your ability to visualize well. But there is no harm in trying it, because unlike drugs, creative visualization has no side effects.

Practice any of these visualization techniques three times a day for one week and observe your health improve.

Did you know that it is only recently that medical doctors have accepted how important the power of the mind is in influencing the immune system of the human body? Many decades passed before these men of science decided to test the proposition that the brain is involved in the optimum functioning of the different body systems. Recent research shows the undeniable connection --the link-- between mind and body, which challenged the long-held medical assumption. A new science called psychoneuroimmunology or PNI, the study of how the mind affects health and bodily functions, has come out of such research.

A psychologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Lean Achterberg, suggests that emotion may form the link between mind and immunity. “Many of the autonomic functions connected with health and disease,” she explains,” are emotionally triggered.”

Exercises which encourage relaxation and mental activities such as creative visualization, positive thinking, and guided imagery produce subtle changes in the emotions which can trigger either a positive or a negative effect on the immune system. This explains why positive imaging techniques have resulted in dramatic healings in people with very serious illnesses, including cancer.

OMNI magazine claims (February, 1989), in a cover article entitled “Mind Exercises That Boost Your Immune System”:

“As far back as the Thirties, Edmund Jacobson found that if you imagine or visualize yourself doing a particular action - say, lifting an object with your right arm - the muscles in that arm show increased electrical activity. Other scientists have found that imagining an object moving across the sky produces more eye movements than visualizing a stationary object.”

One of the most dramatic applications of imagery in coping with illness is the work of Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist in Dallas, Texas. “By combining relaxation with personalized images,” reports OMNI magazine, “he has helped terminal cancer patients reduce the size of their tumors and sometimes experience complete remission of the disease.”

Many of his patients have benefited from this technique. It simply shows how positive visualization can help alleviate - if not totally cure - various diseases including systemic lupus erythomatosus, migraine, chronic back pain, hyperthyroidism, high blood pressure, hyper-acidity, etc.

However, individual differences have to be taken into consideration when discussing each patient’s progress. It’s understandable that individuals have varying abilities to visualize or create mental images clearly; some people will benefit more from positive-imagery techniques than others

Nevertheless, if visualization can help people overcome diseases, it could possibly help healthy individuals keep their immune system in top shape. Says OMNI magazine: “Practicing daily positive-imaging techniques may, like a balanced diet and physical exercise routine, tip the scales of health toward wellness.”

The Simonton process of visualization for cancer

Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist, and his wife, Stephanie Matthews-Simonton, a psychotherapist and counselor specializing in cancer patients, have developed a special visualization or imaging technique for the treatment of cancer which is now popularly known as the Simonton process. Ridiculed at first by the medical profession, the Simonton process is now being used in at least five hospitals across the United States to fight cancer.

The technique itself is the height of simplicity and utilizes the tremendous powers of the mind, specifically its faculty for visualization and imagination, to control cancer. First, the patient is shown what a normal healthy cell looks like. Next, he is asked to imagine a battle going on between the cancer cell and the normal cell. He is asked to visualize a concrete image that will represent the cancer cell and another image of the normal cell. Then he is asked to see the normal cell winning the battle against the cancer cell.

One youngster represented the normal cell as the video game character Pacman and the cancer cell as the “ghosts” (enemies of Pacman), and then he saw Pacman eating up the ghosts until they were all gone.

A housewife saw her cancer cell as dirt and the normal cell as a vacuum cleaner. She visualized the vacuum cleaner swallowing up all the dirt until everything was smooth and clean.

Patients are asked to do this type of visualization three times a day for 15 minutes each time. And the results of the initial experiments in visualization to cure cancer were nothing short of miraculous. Of course, being medical practitioners, Dr. Simonton and his psychologist wife were aware of the placebo effect and spontaneous remission of illness. As long as they were getting good results with the technique, it didn’t seem to matter whether it was placebo or spontaneous remission.

The Simontons also noticed that those who got cured had a distinct personality. They all had a strong will to live and did everything to get well. Those who didn’t succeed had resigned themselves to their fate.

While the Simontons were exploring the motivation of cancer patients, they were also looking into two interesting areas of research at that time: biofeedback and the surveillance theory. Both areas had something to do with the influence of the mind over body processes. Stephanie Simonton explains in her book The Healing Family:

In biofeedback training, an individual is hooked up to a device that feeds back information on his physiological processes. A patient with tachycardia, an irregular heartbeat, might be hooked up to an oscilloscope, which will give a constant visual readout of the heartbeat. The patient watches the monitor while attempting to relax…when he succeeds in slowing his heartbeat through his thinking, he is rewarded immediately by seeing that fact on visual display.

The surveillance theory holds that the immune system does in fact produce ‘killer cells’ which seek out and destroy stray cancer cells many times in our lives, and it is when this system breaks down, that the disease can take hold. When most patients are diagnosed with cancer, surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy are used to destroy as much of the tumor as possible. But once the cancer is reduced, we wondered if the immune system could be reactivated to seek out and destroy the remaining cancer cells.

The Simontons reasoned that since people can learn how to influence their blood flow and heart rate by using their minds, they could also learn to influence their immune system. Later research proved their approach to be valid.

For instance, according to the Time-Life Book The Power of Healing, “chronic stress causes the brain to release into the body a host of hormones that are potent inhibitors of the immune system”. “This may explain why people experience increased rates of infection, cancer, arthritis, and many other ailments after losing a spouse.” Dr. R.W. Berthop and his associates in Australia found that blood samples of bereaved individuals showed a much lower level of lymphocyte activity than was present in the control group’s samples. Lymphocytes are a variety of white blood cells consisting of T cells and B cells, both critical to the action of the immune system. T cells directly attack disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and toxins, and regulate the other parts of the immune system. B cells produce antibodies, which neutralize invaders or mark them for destruction by other agents of the immune system.

The Power of Healing concludes: “The idea that there is a mental element to healing has gained acceptance within the medical establishment in recent years. Many physicians who once discounted the mind’s ability to influence healing are now reconsidering, in the light of new scientific evidence. All these have led some physicians and medical institutions toward a more holistic approach, to treating the body and mind as a unit rather than as two distinct entities. Inherent in this philosophy is the belief that patients must be active participants in the treatment of their illnesses.

Using visualization for minor ailments

Today, many scientific breakthroughs have proven that minor infections and viruses may be healed, or at least lessened in severity by employing mental techniques similar to those used by cancer patients who have successfully shrunk tumors through positive imaging or visualization.

The theory is that creative visualization can create the same physiological changes in the body that a real experience can. For example, if you imagine squeezing a lemon into you mouth, you will most likely salivate, the same way as when a real lemon is actually being squeezed into your mouth. Einstein once declared that, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In the 1985 World Conference on Imaging, reports OMNI magazine (February 1989), registered nurse Carol Fajoni observed that “people who used imagery techniques to heal wounds recovered more quickly than those who did not. In workshops, the same technique has been used by individuals suffering from colds with similar results.” The process has been hailed as a positive breakthrough and is currently being used by more enlightened doctors, according to OMNI magazine.

Visualize that part of your body which is causing the problem. Then erase the negative image and instead picture that organ or part to be healthy. Let's say you have a sinus infection. Just picture your sinus passageways and cavities as beginning to unclog. Or if you have a kidney disorder, imagine a sick-looking kidney metamorphose into a healthier one.

“In trying to envision yourself healthy, you need not view realistic representations of the ailing body part. Instead, imagine a virus as tiny spots on a blackboard that need erasing. Imagine yourself building new, healthy cells or sending cleaning blood to an unhealthy organ or area.”

“If you have a headache, picture your brain as a rough, bumpy road that needs smoothing and proceed to smooth it out. The point is to focus on the area you believe is causing you to feel sick, and to concentrate on visualizing or imaging it to be well. The more clearly and vividly you can do this, the more effective the technique becomes.”

Another method for banishing pain was developed by Russian memory expert, Solomon V. Sherehevskii, as reported by Russian psychologist Professor Luria. To banish pain, such as a headache, Sherehevskii would visualize the pain as having an actual shape, mass and color. Then, when he had a “tangible” image of the pain in his mind, he would visualize or imagine this concrete picture slowly becoming smaller and smaller until it disappeared from his mental vision. The real pain disappears with it. Others have modified this same technique and suggest that you imagine a big bird or eagle taking the concrete image of the pain away. As it flies over the horizon, see it becoming smaller until it disappears from your view. The actual pain will disappear with it.

Of course, the effectiveness of this imaging technique depends on the strength of your desire to improve your health and your ability to visualize well. But there is no harm in trying it, because unlike drugs, creative visualization has no side effects.

Practice any of these visualization techniques three times a day for one week and observe your health improve.

Sunday, 6 March 2016

How can we know ourself?

Questioner: How can

we know ourselves?

Jiddu

Krishnamurti: You know your face because you have often looked at it reflected

in the mirror. Now, there is a mirror in which you

can see yourself entirely - not your face, but all that you think, all that you

feel, your motives, your appetites, your urges and fears. That mirror is the

mirror of relationship: the relationship between you and your parents, between

you and your teachers, between you and the river, the trees, the earth, between

you and your thoughts. Relationship is a mirror in which you can see yourself,

not as you would wish to be, but as you are. I may wish, when looking in an

ordinary mirror, that it would show me to be beautiful, but that does not

happen because the mirror reflects my face exactly as it is and I cannot

deceive myself. Similarly, I can see myself exactly as I am in the mirror of my

relationship with others. I can observe how I talk to people: most politely to

those who I think can give me something, and rudely or contemptuously to those

who cannot. I am attentive to those I am afraid of. I get up when important

people come in, but when the servant enters I pay no attention. So, by

observing myself in relationship, I have found out how falsely I respect

people, have I not? And I can also discover myself as I am in my relationship

with the trees and the birds, with ideas and books.

You may have all the

academic degrees in the world, but if you don't know yourself you are a most

stupid person. To know oneself is the very purpose of all education. Without

self-knowledge,merely to gather facts or take notes so that you can pass

examinations is a stupid way of existence. You may be able to quote the Bhagavad

Gita, the Upanishads, the Koran and the Bible, but unless you know yourself you

are like a parrot repeating words. Whereas, the moment you begin to know

yourself, however little, there is already set going an extraordinary process

of creativeness. It is a discovery to suddenly see yourself as you actually

are: greedy, quarrelsome, angry, envious, stupid. To see the fact without

trying to alter it, just to see exactly what you are is an astonishing

revelation. From there you can go deeper and deeper, infinitely, because there

is no end to self-knowledge.

Through

self-knowledge you begin to find out what is God, what is truth, what is that

state which is timeless. Your teacher may pass on to you the knowledge which he

received from his teacher, and you may do well in your examinations, get a

degree and all the rest of it; but, without knowing yourself as you know your

own face in the mirror, all other knowledge has very little meaning. Learned

people who don't know themselves are really unintelligent; they don't know what

thinking is, what life is. That is why it is important for the educator to be

educated in the true sense of the word, which means that he must know the

workings of his own mind and heart, see himself exactly as he is in the mirror

of relationship. Self-knowledge is the beginning of wisdom. in self-knowledge

is the whole universe; it embraces all the struggles of humanity.Friday, 19 February 2016

We need a new language to talk about the economy - With determined effort, the terms in which policies get discussed can be changed.

Tom Clark in The Guardian

The images used by politicians can simplify difficult theories, but they are also being used to mislead us

John Maynard Keynes with Harry Dexter White in 1946. ‘Keynes was a master of the disruptive metaphor.’ Photograph: Thomas D McAvoy/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

The engineer-turned-economist Bill Phillips illustrated this insight by building a marvellous machine that shunted coloured water about to illustrate how the components of national income related to one another. But there is no need to go to the lengths of constructing a physical metaphor to make the point about how the bubbling stream of a healthy economy can wash away the debris of debt. Or, indeed, how decisive interventions can be required to clear blockages in the arteries of finance.

The question endlessly put to the Labour opposition is whether it can put together a “credible, costed package of alternative economic plans”, and doing that will, of course, have to be part of the answer – but only part. For no such programme, whether it stacks up or not, will compete with Osborne’s until the public can be persuaded to talk about the economy differently.

John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, has put great effort into assembling brainy economists to help refine his detailed commitments, but the results of their deliberations will likely attract even less attention than his one rhetorical flourish to date – “socialism with an iPad”. A creative writing competition might do more to help him prevail in the battles ahead.

‘The big ideas that might make a difference – targeting higher inflation, printing money, or ploughing public funds into infrastructure – remain too contentious for politicians to voice out loud.’ Illustration: Ben Jennings

Banks trembling, shares tumbling and gathering fears of a new slump. The start of 2016 has been chilling for a global economy that has still to shake off the crisis of 2008. Worse, there is no agreement on what to do should the worst happen again. The big ideas that might make a difference – targeting higher inflation, printing money to give consumers something to spend with, or ploughing serious public funds into infrastructure – remain too contentious for politicians to voice out loud. That is a shame, because history suggests that the words they use matter.

Of course policies and theories have to pass muster, but just as significant in determining which ones end up being pursued are the language in which they are discussed. A smart metaphor can do more to shift the sense of the possible than the negative interest rates that increasingly desperate central bankers are relying on to alter the mood.

From economics seminar rooms to rage-pumped Donald Trump rallies there is a consensus on one thing: we need to do better next time. The last recession was followed by years of anaemic growth and squeezed pay, and taxpayers saddled with the bill for bailing out the banks. Nobody is going to be thrilled with that mix, but the despair is most acute on the left.

A crisis caused by footloose finance and preceded by decades in which the rich had raced ahead of the rest might have ushered in a new order of stability and fair shares. Instead we have quantitative easing – which puffs up asset prices for the haves and renders homes less affordable for the have-nots – and fiscal austerity, which makes the poor poorer and also leaves them more exposed, by knocking down the old storm defences of the welfare state. In the US, the top 1% grabbed more than half the total growth in the first five years of recovery, while in the UK, George Osborne, a chancellor who saw no choice to imposing the bedroom tax, still found room to trim the tax rate on top incomes.

None of this should have been possible, but it was successfully sold as necessary. To understand how, we must reckon with the deep foundations of economic orthodoxy in our culture, especially the language.

It was, RH Tawney explained, the genius of the Reformation, the ideological revolution that readied the way for capitalism, to reimagine the “natural frailty” of human greed “into a resounding virtue”. Whereas poverty, in medieval religious theory at least, had been next to godliness, early modern thinkers from Hobbes to Smith equated wealth with worth. Trade became respectable, and lending money for profit, which had been sinful usury, became a fruitful outlet for thrift. Credit became interwoven with honour and pride, while debt was shot through with weighty moral obligations.

These are the orthodox financial prejudices that have, with brief exceptions, held sway ever since – in Gladstone’s red box as much as Thatcher’s handbag. When the 2008 economic storm hit (a metaphor which itself does ideological work, implying an act of nature rather than a crisis of human folly) the then shadow chancellor Osborne reached for a tried and tested script. “The cupboard is bare,”he sternly announced, likening bankrupt Britain to an over-indebted home.

Economists have objected to lazy comparisons between domestic and national finances for the best part of a century: governments can tax, grow or even print their way out of debt, three important escape routes not open to individuals. In the 30 years after the second world war there were deficits in all but six. But far from this leaving Britain’s cupboard bare, the national debt dwindled from 250% to 50% of GDP.

So the household metaphor is deeply misleading but it remains irresistible to politicians and powerful with the public. It offers a way to make sense of the otherwise baffling billions in national debt through analogy with everyday experience. Furthermore, explains Jonathan Charteris-Black, an expert on rhetoric at the University of the West of England, it embeds “one of the most widely used of all political images: the nation as family, with the government as responsible parent”.

It is all so familiar that only restless, malcontent minds will argue back against the claim that There Is No Alternative. But the awkward squad should not lose heart: with determined effort, the terms in which policies get discussed can sometimes be changed. One modest example was the one-off charge made on the utilities soon after Labour came to power in 1997. Few taxes are popular, but by being badged a “windfall levy” this one came to be seen as a fair way to share good fortune that had dropped into the lap of these firms.

Looking further back, Keynes was a master of the disruptive metaphor. He described the “animal spirits” of investors whose rationality he questioned, and dismissed the self-styled “wolves and tiger” of industry as pathetically “domesticated” beasts. He was even credited with livening technical debate about the efficacy of monetary policy in a liquidity trap by talking of “pushing on a piece of string”. Keynesians across the Atlantic, such as Lauchlin Currie, rationalised the deficits of Roosevelt’s New Deal as “pump priming” the economy. The image here is of an old-fashioned well, where you have to pour in a little fluid to clear air from the valve, which then allows you to pump out a far larger volume of water. It had intuitive appeal for the very many Americans who had then been raised on farms, but hydraulics remains a promising source of imagery. Where orthodox economics and the moralising that goes with it emphasises solid “stocks”, assets and liabilities of particular values – a nasty debt, a nice nest egg or indeed an empty cupboard – the real economy operates through continuous “flows” of payment and activity.

Banks trembling, shares tumbling and gathering fears of a new slump. The start of 2016 has been chilling for a global economy that has still to shake off the crisis of 2008. Worse, there is no agreement on what to do should the worst happen again. The big ideas that might make a difference – targeting higher inflation, printing money to give consumers something to spend with, or ploughing serious public funds into infrastructure – remain too contentious for politicians to voice out loud. That is a shame, because history suggests that the words they use matter.

Of course policies and theories have to pass muster, but just as significant in determining which ones end up being pursued are the language in which they are discussed. A smart metaphor can do more to shift the sense of the possible than the negative interest rates that increasingly desperate central bankers are relying on to alter the mood.

From economics seminar rooms to rage-pumped Donald Trump rallies there is a consensus on one thing: we need to do better next time. The last recession was followed by years of anaemic growth and squeezed pay, and taxpayers saddled with the bill for bailing out the banks. Nobody is going to be thrilled with that mix, but the despair is most acute on the left.

A crisis caused by footloose finance and preceded by decades in which the rich had raced ahead of the rest might have ushered in a new order of stability and fair shares. Instead we have quantitative easing – which puffs up asset prices for the haves and renders homes less affordable for the have-nots – and fiscal austerity, which makes the poor poorer and also leaves them more exposed, by knocking down the old storm defences of the welfare state. In the US, the top 1% grabbed more than half the total growth in the first five years of recovery, while in the UK, George Osborne, a chancellor who saw no choice to imposing the bedroom tax, still found room to trim the tax rate on top incomes.

None of this should have been possible, but it was successfully sold as necessary. To understand how, we must reckon with the deep foundations of economic orthodoxy in our culture, especially the language.

It was, RH Tawney explained, the genius of the Reformation, the ideological revolution that readied the way for capitalism, to reimagine the “natural frailty” of human greed “into a resounding virtue”. Whereas poverty, in medieval religious theory at least, had been next to godliness, early modern thinkers from Hobbes to Smith equated wealth with worth. Trade became respectable, and lending money for profit, which had been sinful usury, became a fruitful outlet for thrift. Credit became interwoven with honour and pride, while debt was shot through with weighty moral obligations.

These are the orthodox financial prejudices that have, with brief exceptions, held sway ever since – in Gladstone’s red box as much as Thatcher’s handbag. When the 2008 economic storm hit (a metaphor which itself does ideological work, implying an act of nature rather than a crisis of human folly) the then shadow chancellor Osborne reached for a tried and tested script. “The cupboard is bare,”he sternly announced, likening bankrupt Britain to an over-indebted home.

Economists have objected to lazy comparisons between domestic and national finances for the best part of a century: governments can tax, grow or even print their way out of debt, three important escape routes not open to individuals. In the 30 years after the second world war there were deficits in all but six. But far from this leaving Britain’s cupboard bare, the national debt dwindled from 250% to 50% of GDP.

So the household metaphor is deeply misleading but it remains irresistible to politicians and powerful with the public. It offers a way to make sense of the otherwise baffling billions in national debt through analogy with everyday experience. Furthermore, explains Jonathan Charteris-Black, an expert on rhetoric at the University of the West of England, it embeds “one of the most widely used of all political images: the nation as family, with the government as responsible parent”.

It is all so familiar that only restless, malcontent minds will argue back against the claim that There Is No Alternative. But the awkward squad should not lose heart: with determined effort, the terms in which policies get discussed can sometimes be changed. One modest example was the one-off charge made on the utilities soon after Labour came to power in 1997. Few taxes are popular, but by being badged a “windfall levy” this one came to be seen as a fair way to share good fortune that had dropped into the lap of these firms.

Looking further back, Keynes was a master of the disruptive metaphor. He described the “animal spirits” of investors whose rationality he questioned, and dismissed the self-styled “wolves and tiger” of industry as pathetically “domesticated” beasts. He was even credited with livening technical debate about the efficacy of monetary policy in a liquidity trap by talking of “pushing on a piece of string”. Keynesians across the Atlantic, such as Lauchlin Currie, rationalised the deficits of Roosevelt’s New Deal as “pump priming” the economy. The image here is of an old-fashioned well, where you have to pour in a little fluid to clear air from the valve, which then allows you to pump out a far larger volume of water. It had intuitive appeal for the very many Americans who had then been raised on farms, but hydraulics remains a promising source of imagery. Where orthodox economics and the moralising that goes with it emphasises solid “stocks”, assets and liabilities of particular values – a nasty debt, a nice nest egg or indeed an empty cupboard – the real economy operates through continuous “flows” of payment and activity.

John Maynard Keynes with Harry Dexter White in 1946. ‘Keynes was a master of the disruptive metaphor.’ Photograph: Thomas D McAvoy/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

The engineer-turned-economist Bill Phillips illustrated this insight by building a marvellous machine that shunted coloured water about to illustrate how the components of national income related to one another. But there is no need to go to the lengths of constructing a physical metaphor to make the point about how the bubbling stream of a healthy economy can wash away the debris of debt. Or, indeed, how decisive interventions can be required to clear blockages in the arteries of finance.

The question endlessly put to the Labour opposition is whether it can put together a “credible, costed package of alternative economic plans”, and doing that will, of course, have to be part of the answer – but only part. For no such programme, whether it stacks up or not, will compete with Osborne’s until the public can be persuaded to talk about the economy differently.

John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, has put great effort into assembling brainy economists to help refine his detailed commitments, but the results of their deliberations will likely attract even less attention than his one rhetorical flourish to date – “socialism with an iPad”. A creative writing competition might do more to help him prevail in the battles ahead.

Monday, 2 February 2015

Why sport needs to be playful

Ed Smith in Cricinfo

I'd like to make a case for sport. My argument ignores the usual theories - weight lost, arteries unclogged, endorphins released, friendships made, purpose gained, associations formed, communities knit together.

All true enough. But my theme is different. My focus is the value of play, within sport and also in life. Because it is usually perceived as the opposite of serious, we tend to trivialise play. In fact, play needs to be taken much more seriously.

I am making a deliberate distinction between merely "doing" sport and really "playing" sport. For it is possible to play sport unplayfully, joylessly going through the motions, merely acting out a prearranged plan, becoming a cog in a cold machine, becoming totally closed to instinct or mischief. Indeed, one of the ironies of the development of modern sport - both professional and, more depressingly, amateur - is that it has become progressively less playful.

There is, I think, a unique category of play, different and special: playful play. This is not, obviously, the exclusive preserve of sport - it is also central to good conversation, intellectual life, music and scientific invention. In my personal experience, however, I feel a great debt to sport in particular. Perhaps unusually for a professional sportsman, I am reflective, analytical and happy with long periods of solitude. Playing sport - really playing sport - was not only a counterpoint (and a pleasure). It has also been a catalyst.

My experience is backed up by academic research. I recently read Play, Playfulness, Creativity and Innovation by the scientists Patrick Bateson and Paul Martin. I recommend it to sports fans and sceptics alike.

Much of the book is unconnected to sport. According to Bateson and Martin, play is "an evolved biological adaptation that enables the individual to escape from local optima and discover better solutions". They use the example of a squirrel swinging on a branch merely playfully, which by accident enables it to reach nuts that were previously inaccessible. So the change in behaviour becomes a learned modification; an activity that was apparently without purpose becomes all too useful. That is how kids learn, too, the authors propose: more playful children become creative adults.

The word "creative" has become a corporate cliché. Corporate life wants everyone to be creative, which is a bit like a coach wanting every batsman to score a hundred. Well, of course. But how? The link between creativity and playfulness is rarely accounted for. As the zoologist George Bartholomew concluded: "Creativity often appears to be some complex function of play… The most profoundly creative humans of course never lose this."

Alexander Fleming, who created the penicillin vaccine, was described, disapprovingly, by his boss as treating research like a game. When asked what he did, Fleming replied, "I play with microbes… it is very pleasant to break the rules and to be able to find something that nobody had thought of."

In contrast, "the meeting" - enforced boredom orchestrated by authority - is the most anti-playful invention known to man. Any event that is closed, bounded and explicitly humourless is almost certain to be uncreative. In calling a meeting, in the traditional sense, corporations increase the probability of not finding a solution.

Thinking about play has encouraged me to rethink certain aspects of sport. When I was still a professional player, I naturally revered high performance - the score on the board. Now, from the vantage point of retirement, I can see that the only way to "win" at sport, in the deepest sense, is also to enjoy it.

I was fascinated while commentating with Sunil Gavaskar last summer to hear the master batsman say he enjoyed the second half of his career far more than the first. This from the man who scored 20 Test hundreds in his first 50 matches! A slight diminution in output was outweighed, from Gavaskar's perspective, by a far more joyful approach to batting.

When Tiger Woods was in his pomp, many of my colleagues used him as a model, perceiving him as the ultimate sportsman. But I was never so sure. Was it really so enviable, Woods' life? To Woods, sport seemed to be about negating his humanity, ironing the play out of his game rather than embracing it. We might admire his iron willpower. But how many people would a Woods-style career really suit? Santi Cazorla, the impish and mischievous Spain and Arsenal midfielder, seems to have more fun in 90 minutes than Woods has in an entire season.

For the apotheosis of unplayful sport, look no further than Lance Armstrong. Forget the cheating and the bullying for a moment. What could be more depressing than tweeting a photo of yourself sitting alone in suburban luxury surrounded by (fraudulent) yellow jerseys? Were there no happy memories, in his mind rather than his camera, to soften the blow of disgrace?

It is also possible for sportsmen, even within the fiercest battles, to cooperate in permitting an air of playfulness.

You see this occasionally in tennis. Most of the time, of course, tactics are explicitly reductionist and self-interested: doing what the opponent least wants. But occasionally a point develops that is different. Both players are constantly trying to win the point, but they also implicitly - and surely subconsciously - enter a different mode. A slice is followed by another slice (apparently inexplicably), a change of pace leads to another change of pace. In short, a conversation develops, something to be enjoyed and extended. And won. For I'm not interested in showmanship here, exhibition-style showing off or playing to the gallery. But there also are moments within proper combat when players are trying to do three things simultaneously - to win, to play (for the fun of it, selfishly) and also to encourage a similar mood on the other side of the net. It must be a rarefied, complete mode of living.

In normal life there is a simpler reason to stay playful. "We don't stop playing because we grow old," George Bernard Shaw remarked, "we grow old because we stop playing."

Friday, 2 January 2015

Easy to sneer at arts graduates. But we’ll need their skills

Creative types have the confidence to take risks. And they understand that money isn’t everything

Anthony Ward Thomas, of Ward Thomas Removals, has a problem that he shares with the public. After a life spent turning a man with a van into a multimillion-pound firm, he finds his children are not interested in taking over. “They have different interests,” he says. He is sad, but agrees “there should be no divine right that they get the business”. They should make their own way in the world. This they are doing. His daughters are country and western singers and his son is an actor. I doubt if they are as rich.

When penal supertaxes were ended in the 1980s, the surplus spending power was expected to go on cars, yachts and houses. Much of it did. But a new form of supertax emerged, no less insistent than the last. It was called children. And not just any children, who might look after their parents in old age, but ones seeking a life of fashionable but impecunious “creativity”.

Statistics say the chief cost of child-rearing occurs in the teens. To get an offspring housed, clothed, fed and educated to the age of 21 takes an average of £225,000, or half a million if privately educated. This has more than doubled over the past decade. But ask most parents, and the expense does not stop at 21. It continues through further education, travel, internship, ongoing board and lodging, even early marriage.

Thousands the world over are returning to live at home after university. Australians have “boomerang” children, Italians bamboccioni (big babies), the Japanese parasaito shinguru (parasite singles) and the Germans “hotel mama”. To the youth psychologist Haim Omer, this “entitled dependency” has become “the new hedonism … an ideology at the parents’ expense, nothing less than a pandemic”. Behind this phenomenon stands the famous “bank of mum and dad”, notably in the matter of housing: its motto is “pay up or we stay”. In Britain this bespoke baby bank reportedly hands out a staggering £27bn annually. The loans have nothing to do with investment. The bank would go swiftly bust if they did. Money is spent, above all, on property. A trivial £600m is reckoned to go on business ventures. The bank is too proud to fail. The Ward Thomas branch of this bank is more specific. I am not privy to the family’s circumstances, but if the bank is like many I know, it existed to fund careers in “something creative”, often what the parents once called a hobby but their children consider a talent in need of full occupational rein. This bank of mum and dad becomes a private arts council, far outstripping the resources available to the real one.

A cultural economist might welcome this. It forces down pay and costs in the arts, making it cheaper to run literary festivals, music venues, provincial rep, galleries and publishing. Children are far more expert at extracting “grants” from parents than is the Treasury; HMRC has no clout to compare with “Edinburgh could be our big break, Dad”.

But the phenomenon has consequences. It biases “subsidy”, and the jobs to which they give access, towards the children of the rich. It also seriously distorts higher education, with a booming demand for courses in drama, dance, fine art, music, film, photography, design and creative writing.

Britain now has 160,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students in “creative arts and design”, with more than 20,000 in drama alone. This is more than in the whole of engineering or in maths and computing combined.

This academic bias is far beyond what the market for such skills can sustain. Just 28% of graduates in performing arts find jobs in the arts or media, while almost the same proportion find their way into retail and catering. Britain’s bursting drama schools are training a better class of waiter.

Does this matter? The lethargy afflicting Japan’s once-tiger economy over the past decade is attributed to precisely this career demotivation of the post-salaryman generation. Young Japanese have been able to afford to turn away from their parents’ grinding labour and its karoshi, or death from overwork. A similar collapse may one day afflict Chinese entrepreneurialism. Even the continued vitality of the US and Germany is attributed not to natives but to migrant talent drawn from less favoured countries.

Europe is in the economic doldrums. It may produce the best opera singers and write the best novels, but its cars and computers are rubbish. Its bankers can hedge markets and its tour operators can market hedges, but the funds come from Asian enterprise. Either it will discourage its young from dancing, film-making and creative writing and galvanise it to risk-taking innovation, or it will slither into becoming a gigantic Bournemouth, living off the dwindling fat of its past.

So says the economist. Or should we put more faith in the dynamic of a humanistic education? Graduates in the performing arts are actually high achievers in finding work outside their skill group, probably through enhanced confidence and articulacy. They take chances and do not regard money as everything. They seem better equipped to use their imagination and challenge conventional wisdom.

The pop science bestseller Sapiens, by Yuval Noah Harari, suggests that humans “are now beginning to break the laws of natural selection, replacing them with the laws of intelligent design”. Human advance through natural selection has reached its limit. Strides forward will now be technological rather than biological.

For Harari the question for our species is not “what do we want to become?”, but the far harder question, “what do we want to want?”. Who makes the choices? The answer will not lie in the brave new world of cyborgs and robots. It can only lie in what are rightly called the humanities, the history and imagination of human beings. Alexander Pope was always right: “The proper study of mankind is man.”

Most British adults now believe their offspring will be poorer than themselves. Yet millions indulge their children in careers they know will yield neither financial reward nor national advantage. I am not convinced the world they are creating will really be worse off for that. There is plenty for the robots to do, like running removal firms.

Sunday, 6 October 2013

Rise and shine: the daily routines of history's most creative minds

Benjamin Franklin spent his mornings naked. Patricia Highsmith ate only bacon and eggs. Marcel Proust breakfasted on opium and croissants. The path to greatness is paved with a thousand tiny rituals (and a fair bit of substance abuse) – but six key rules emerge

One morning this summer, I got up at first light – I'd left the blinds open the night before – then drank a strong cup of coffee, sat near-naked by an open window for an hour, worked all morning, then had a martini with lunch. I took a long afternoon walk, and for the rest of the week experimented with never working for more than three hours at a stretch.

This was all in an effort to adopt the rituals of some great artists and thinkers: the rising-at-dawn bit came from Ernest Hemingway, who was up at around 5.30am, even if he'd been drinking the night before; the strong coffee was borrowed from Beethoven, who personally counted out the 60 beans his morning cup required.Benjamin Franklin swore by "air baths", which was his term for sitting around naked in the morning, whatever the weather. And the midday cocktail was a favourite of VS Pritchett (among many others). I couldn't try every trick I discovered in a new book, Daily Rituals: How Great Minds Make Time, Find Inspiration And Get To Work; oddly, my girlfriend was unwilling to play the role of Freud's wife, who put toothpaste on his toothbrush each day to save him time. Still, I learned a lot. For example: did you know that lunchtime martinis aren't conducive to productivity?

As a writer working from home, of course, I have an unusual degree of control over my schedule – not everyone could run such an experiment. But for anyone who thinks of their work as creative, or who pursues creative projects in their spare time, reading about the habits of the successful, can be addictive. Partly, that's because it's comforting to learn that even Franz Kafkastruggled with the demands of his day job, or that Franklin was chronically disorganised. But it's also because of a covert thought that sounds delusionally arrogant if expressed out loud: just maybe, if I took very hot baths like Flaubert, or amphetamines like Auden, I might inch closer to their genius.

Several weeks later, I'm no longer taking "air baths", while the lunchtime martini didn't last more than a day (I mean, come on). But I'm still rising early and, when time allows, taking long walks. Two big insights have emerged. One is how ill-suited the nine-to-five routine is to most desk-based jobs involving mental focus; it turns out I get far more done when I start earlier, end a little later, and don't even pretend to do brain work for several hours in the middle. The other is the importance of momentum. When I get straight down to something really important early in the morning, before checking email, before interruptions from others, it beneficially alters the feel of the whole day: once interruptions do arise, they're never quite so problematic. Another technique I couldn't manage without comes from the writer and consultant Tony Schwartz: use a timer to work in 90-minute "sprints", interspersed with signficant breaks. (Thanks to this, I'm far better than I used to be at separating work from faffing around, rather than spending half the day flailing around in a mixture of the two.)

The one true lesson of the book, says its author, Mason Currey, is that "there's no one way to get things done". For every Joyce Carol Oates, industriously plugging away from 8am to 1pm and again from 4pm to 7pm, or Anthony Trollope, timing himself typing 250 words per quarter-hour, there's a Sylvia Plath, unable to stick to a schedule. (Or a Friedrich Schiller, who could only write in the presence of the smell of rotting apples.) Still, some patterns do emerge. Here, then, are six lessons from history's most creative minds.

1. Be a morning person

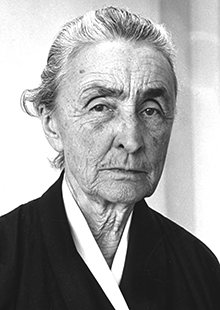

Georgia O'Keeffe: one of a majority of very early morning risers. Photograph: AP

Georgia O'Keeffe: one of a majority of very early morning risers. Photograph: AP

It's not that there aren't successful night owls: Marcel Proust, for one, rose sometime between 3pm and 6pm, immediately smoked opium powders to relieve his asthma, then rang for his coffee and croissant. But very early risers form a clear majority, including everyone from Mozart to Georgia O'Keeffe to Frank Lloyd Wright. (The 18th-century theologian Jonathan Edwards, Currey tells us, went so far as to argue that Jesus had endorsed early rising "by his rising from the grave very early".) For some, waking at 5am or 6am is a necessity, the only way to combine their writing or painting with the demands of a job, raising children, or both. For others, it's a way to avoid interruption: at that hour, as Hemingway wrote, "There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write." There's another, surprising argument in favour of rising early, which might persuade sceptics: that early-morning drowsiness might actually be helpful. At one point in his career, the novelist Nicholson Baker took to getting up at 4.30am, and he liked what it did to his brain: "The mind is newly cleansed, but it's also befuddled… I found that I wrote differently then."

Psychologists categorise people by what they call, rather charmingly, "morningness" and "eveningness", but it's not clear that either is objectively superior. There is evidence that morning people are happier and more conscientious, but also that night owls might be more intelligent. If you're determined to join the ranks of the early risers, the crucial trick is to start getting up at the same time daily, but to go to bed only when you're truly tired. You might sacrifice a day or two to exhaustion, but you'll adjust to your new schedule more rapidly.

2. Don't give up the day job

TS Eliot’s day job at Lloyds bank gave him crucial financial security. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

TS Eliot’s day job at Lloyds bank gave him crucial financial security. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

"Time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy," Franz Kafka complained to his fiancee, "and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible, then one must try to wriggle through by subtle manoeuvres." He crammed in his writing between 10.30pm and the small hours of the morning. But in truth, a "pleasant, straightforward life" might not have been preferable, artistically speaking: Kafka, who worked in an insurance office, was one of many artists who have thrived on fitting creative activities around the edges of a busy life. William Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in the afternoons, before commencing his night shift at a power plant; TS Eliot's day job at Lloyds bank gave him crucial financial security; William Carlos Williams, a paediatrician, scribbled poetry on the backs of his prescription pads. Limited time focuses the mind, and the self-discipline required to show up for a job seeps back into the processes of art. "I find that having a job is one of the best things in the world that could happen to me," wroteWallace Stevens, an insurance executive and poet. "It introduces discipline and regularity into one's life." Indeed, one obvious explanation for the alcoholism that pervades the lives of full-time authors is that it's impossible to focus on writing for more than a few hours a day, and, well, you've got to make those other hours pass somehow.

3. Take lots of walks

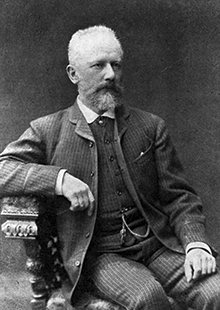

Tchaikovsky 'believed he had to take a walk of exactly two hours a day and that if he returned even a few minutes early, great misfortunes would befall him.' Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Tchaikovsky 'believed he had to take a walk of exactly two hours a day and that if he returned even a few minutes early, great misfortunes would befall him.' Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

There's no shortage of evidence to suggest that walking – especially walking in natural settings, or just lingering amid greenery, even if you don't actually walk much – is associated with increased productivity and proficiency at creative tasks. But Currey was surprised, in researching his book, by the sheer ubiquity of walking, especially in the daily routines of composers, including Beethoven, Mahler, Erik Satie and Tchaikovksy, "who believed he had to take a walk of exactly two hours a day and that if he returned even a few minutes early, great misfortunes would befall him". It's long been observed that doing almost anything other than sitting at a desk can be the best route to novel insights. These days, there's surely an additional factor at play: when you're on a walk, you're physically removed from many of the sources of distraction – televisions, computer screens – that might otherwise interfere with deep thought.

4. Stick to a schedule

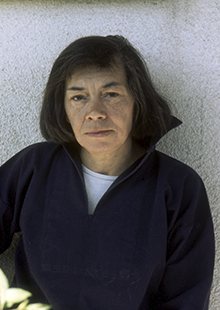

Patricia Highsmith, among others, ate virtually the same thing for every meal, in her case bacon and fried eggs. Photograph: Corbis Sygma

Patricia Highsmith, among others, ate virtually the same thing for every meal, in her case bacon and fried eggs. Photograph: Corbis Sygma

There's not much in common, ritual-wise, between Gustave Flaubert – who woke at 10am daily and then hammered on his ceiling to summon his mother to come and sit on his bed for a chat – and Le Corbusier, up at 6am for his 45 minutes of daily calisthenics. But they each did what they did with iron regularity. "Decide what you want or ought to do with the day," Auden advised, "then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble." (According to legend, Immanuel Kant's neighbours in Königsberg could set their clocks by his 3.30pm walk.) This kind of existence sounds as if it might require intimidating levels of self-discipline, but on closer inspection it often seems to be a kind of safety net: the alternative to a rigid structure is either no artistic creations, for those with day jobs, or the existential terror of no structure at all.

It was William James, the progenitor of modern psychology, who best articulated the mechanism by which a strict routine might help unleash the imagination. Only by rendering many aspects of daily life automatic and habitual, he argued, could we "free our minds to advance to really interesting fields of action". (James fought a lifelong struggle to inculcate such habits in himself.) Subsequent findings about "cognitive bandwidth" and the limitations of willpower have largely substantiated James's hunch: if you waste resources trying to decide when or where to work, you'll impede your capacity to do the work. Don't consider afresh each morning whether to work on your novel for 45 minutes before the day begins; once you've resolved that that's just what you do, it'll be far more likely to happen. It might have been a similar desire to pare down unnecessary decisions that led Patricia Highsmith, among others, to eat virtually the same thing for every meal, in her case bacon and fried eggs. Although Highsmith also collected live snails and, in later life, promulgated anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, so who knows?

5. Practise strategic substance abuse

Ayn Rand took Benzedrine. Photograph: New York Times Co/Getty Images

Ayn Rand took Benzedrine. Photograph: New York Times Co/Getty Images

Almost every potential chemical aid to creativity has been tried at some time or another: Auden, Ayn Rand and Graham Greene had their Benzedrine, the mathematician Paul Erdös had his Ritalin (and his Benzedrine); countless others tried vodka, whisky or gin. But there's only one that has been championed near-universally down the centuries: coffee. Beethoven measured out his beans, Kierkegaard poured black coffee over a cup full of sugar, then gulped down the resulting concoction, which had the consistency of mud; Balzac drank 50 cups a day. It's been suggested that the benefits of caffeine, in terms of heightened focus, might be offset by a decrease in proficiency at more imaginative tasks. But if that's true, it's a lesson creative types have been ignoring for ever. Consume in moderation, though: Balzac died of heart failure at 51.

6. Learn to work anywhere

Agatha Christie didn’t have a desk. Any stable tabletop for her typewriter would do. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

Agatha Christie didn’t have a desk. Any stable tabletop for her typewriter would do. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

One of the most dangerous procrastination-enabling beliefs is the idea that you must find exactly the right environment before you can get down to work. "For years, I said if only I could find a comfortable chair, I would rival Mozart," the American composer Morton Feldman recalled. Somerset Maugham had to face a blank wall before the words would come (any other view, he felt, was too distracting). But the stern message that emerges from many other artists' and authors' experiences is: get over yourself. During Jane Austen's most productive years, at Chawton in Hampshire in the 1810s, she wrote mainly in the family sitting-room, often with her mother sewing nearby. Continually interrupted by visitors, she wrote on scraps of paper that could easily be hidden away. Agatha Christie, Currey writes, had "endless trouble with journalists, who inevitably wanted to photograph the author at her desk": a problematic request, because she didn't have one. Any stable tabletop for her typewriter would do.

In any case, absolute freedom from distraction may not be as advantageous as it sounds. One study recently suggested that some noise, such as the background buzz of a coffee shop, may be preferable to silence, in terms of creativity; moreover, physical mess may be as beneficial for some people as an impeccably tidy workspace is for others. The journalistRon Rosenbaum cherishes a personal theory of "competing concentration": working with the television on, he says, gives him a background distraction to focus against, keeping his attentional muscles flexed and strong.

But there is a broader lesson here. The perfect workspace isn't what leads to brilliant work, just as no other "perfect" routine or ritual will turn you into an artistic genius. Flaubert didn't achieve what he did because of hot baths, but through immeasurable talent and extremely hard work. Which is unfortunate, because I'm really good at running baths.

Benzedrine, naps, an early night: an extract from Daily Rituals

Gertrude Stein

In Everybody's Autobiography, Stein confirmed that she had never been able to write for much more than half an hour a day, but added, "If you write a half-hour a day, it makes a lot of writing year by year." Stein and her lifelong partner, Alice B Toklas, had lunch at about noon and ate an early, light supper. Toklas went to bed early, but Stein liked to stay up arguing and gossiping with visiting friends. After her guests finally left, Stein would wake Toklas, and they would talk over the day before both going to sleep.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven rose at dawn and wasted little time getting down to work. His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care: 60 beans per cup. After his midday meal, he embarked on a long walk, which would occupy much of the rest of the afternoon. As the day wound down, he might stop at a tavern to read the newspapers. Evenings were often spent with company or at the theatre, although in winter he preferred to stay at home and read. He retired early, going to bed at 10pm at the latest.

WH Auden

"Routine, in an intelligent man, is a sign of ambition," Auden wrote in 1958. If that's true, the poet was one of the most ambitious men of his generation. He rose shortly after 6am, made coffee and settled down to work quickly, perhaps after taking a first pass at the crossword. He usually resumed after lunch and continued into the late afternoon. Cocktail hour began at 6.30pm sharp, featuring several strong vodka martinis. Then dinner was served, with copious amounts of wine. To maintain his energy and concentration, he relied on amphetamines, taking Benzedrine each morning. At night, he used Seconal or another sedative to get to sleep.

Sylvia Plath

Plath's journal, which she kept from age 11 until her suicide at 30, records a near-constant struggle to find and stick to a productive writing schedule. Only near the end of her life, separated from her husband, Ted Hughes, and taking care of their two small children alone, did she find a routine that worked for her. She was using sedatives to get to sleep, and when they wore off at about 5am, she would get up and write until the children awoke. Working like this for two months in 1962, she produced nearly all the poems of Ariel.

Alice Munro

In the 1950s, as a young mother taking care of two small children, Munro wrote in the slivers of time between housekeeping and child-rearing. When neighbours dropped in, Munro didn't feel comfortable telling them she was trying to work. She tried renting an office, but the garrulous landlord interrupted her and she hardly got any writing done. It ultimately took her almost two decades to put together the material for her first collection, Dance Of The Happy Shades.

David Foster Wallace

"I usually go in shifts of three or four hours with either naps or fairly diverting do-something-with-other-people things in the middle," Wallace said in 1996, shortly after the publication of Infinite Jest. "So I'll get up at 11 or noon, work till two or three." Later, however, he said he followed a regular writing routine only when the work was going badly. "Once it starts to go, it requires no effort. And then actually the discipline's required in terms of being willing to be away from it and to remember, 'Oh, I have a relationship that I have to nurture, or I have to grocery-shop or pay these bills.' "

Ingmar Bergman

"Do you know what moviemaking is?" Bergman asked in a 1964 interview. "Eight hours of hard work each day to get three minutes of film." But it was also writing scripts, which he did on the remote island of Fårö, Sweden. He followed the same schedule for decades: up at 8am, writing from 9am until noon, then an austere meal. "He eats the same lunch," actorBibi Andersson remembered. "It's some kind of whipped sour milk and strawberry jam – a strange kind of baby food he eats with corn flakes." After lunch, Bergman worked from 1pm to 3pm, then slept for an hour. In the late afternoon he went for a walk or took the ferry to a neighbouring island to pick up the newspapers and the mail. In the evening he read, saw friends, screened a movie, or watched TV (he was particularly fond of Dallas). "I never use drugs or alcohol," Bergman said. "The most I drink is a glass of wine and that makes me incredibly happy."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)