In an exclusive extract from his new book, Owen Jones explains how the political, social and business elites have a stranglehold on the country

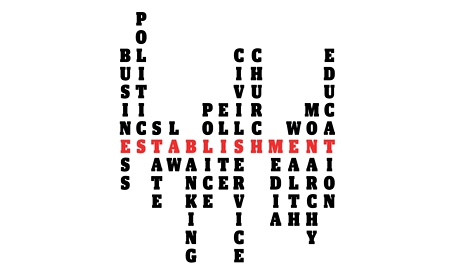

How the establishment connects all areas of life in modern Britain. Photograph: Christophe Gowans/The Guardian

Definitions of "the establishment" share one thing in common: they are always pejorative. Rightwingers tend to see it as the national purveyor of a rampant, morally corrupting social liberalism; for the left, it is more likely to mean a network of public-school and Oxbridge boys dominating the key institutions of British political life.

Here is what I understand the establishment to mean. Today's establishment is made up – as it has always been – of powerful groups that need to protect their position in a democracy in which almost the entire adult population has the right to vote. The establishment represents an attempt on behalf of these groups to "manage" democracy, to make sure that it does not threaten their own interests. In this respect, it might be seen as a firewall that insulates them from the wider population. As the well-connected rightwing blogger and columnist Paul Staines puts it approvingly: "We've had nearly a century of universal suffrage now, and what happens is capital finds ways to protect itself from, you know, the voters."

Back in the 19th century, as calls for universal suffrage gathered strength, there were fears in privileged circles that extending the vote to the poor would pose a mortal threat to their own position – that the lower rungs of society would use their newfound voice to take away power and wealth from those at the top and redistribute it throughout the electorate. "I have heard much on the subject of the working classes in this house which, I confess, has filled me with feelings of some apprehension," Conservative statesman Lord Salisbury told parliament in 1866, in response to plans to extend the suffrage. Giving working-class people the vote would, he stated, tempt them to pass "laws with respect to taxation and property especially favourable to them, and therefore dangerous to all other classes".

The worries of those 19th-century opponents of universal suffrage were not without foundation. In the decades that followed the second world war, constraints were imposed on Britain's powerful interests, including higher taxes and the regulation of private business. This was, after all, the will of the recently enfranchised masses. But today, many of those constraints have been removed or are in the process of being dismantled – and now the establishment is characterised by institutions and ideas that legitimise and protect the concentration of wealth and power in very few hands.

The interests of those who dominate British society are disparate; indeed, they often conflict with one another. The establishment includes politicians who make laws; media barons who set the terms of debate; businesses and financiers who run the economy;police forces that enforce a law that is rigged in favour of the powerful. The establishment is where these interests and worlds intersect, either consciously or unconsciously. It is unified by a common mentality, which holds that those at the top deserve their power and their ever-growing fortunes, and which might be summed up by the advertising slogan "Because I'm worth it". This is the mentality that has driven politicians to pilfer expenses, businesses to avoid tax, and City bankers to demand ever greater bonuses while plunging the world into economic disaster. All of these things are facilitated – even encouraged – by laws that are geared to cracking down on the smallest of misdemeanours committed by those at the bottom of the pecking order – for example, benefit fraud. "One rule for us, one rule for everybody else" might be another way to sum up establishment thinking.

These mentalities owe everything to the shared ideology of the modern establishment, a set of ideas that helps it to rationalise and justify its position and behaviour. Often described as "neoliberalism", this ideology is based around a belief in so-called free markets: in transferring public assets to profit-driven businesses as far as possible; in a degree of opposition – if not hostility – to a formal role for the state in the economy; support for reducing the tax burden on private interests; and the driving back of any form of collective organisation that might challenge the status quo. This ideology is often rationalised as "freedom" – particularly "economic freedom" – and wraps itself in the language of individualism. These are beliefs that the establishment treats as common sense, as being a fact of life, just like the weather.

Not to subscribe to these beliefs is to be outside today's establishment, to be dismissed by it as an eccentric at best, or even as an extremist fringe element. Members of the establishment genuinely believe in this ideology – but it is a set of beliefs and policies that, rather conveniently, guarantees them ever growing personal riches and power.

As well as a shared mentality, the establishment is cemented by financial links and a "revolving door": that is, powerful individuals gliding between the political, corporate and media worlds – or who manage to inhabit these various worlds at the same time. The terms of political debate are, in large part, dictated by a media controlled by a small number of exceptionally rich owners, while thinktanks and political parties are funded by wealthy individuals and corporate interests. Many politicians are on the payroll of private businesses; along with civil servants, they end up working for companies interested in their policy areas, allowing them to profit from their public service – something that gives them a vested interest in an ideology that furthers corporate interests. The business world benefits from the politicians' and civil servants' contacts, as well as an understanding of government structures and experience, allowing private firms to navigate their way to the very heart of power.

Yet there is a logical flaw at the heart of establishment thinking. It may abhor the state – but it is completely dependent on the state to flourish. Bailed-out banks; state-funded infrastructure; the state's protection of property; research and development; a workforce educated at great public expense; the topping up of wages too low to live on; numerous subsidies – all are examples of what could be described as a "socialism for the rich" that marks today's establishment.

This establishment does not receive the scrutiny it deserves. After all, it is the job of the media to shed light on the behaviour of those with power. But the British media is an integral part of the British establishment; its owners share the same underlying assumptions and mantras. Instead, journalists and politicians alike obsessively critique and attack the behaviour of those at the bottom of society. Unemployed people and other benefit claimants; immigrants; public-sector workers – these are groups that have faced critical exposure or even outright vilification. This focus on the relatively powerless is all too convenient in deflecting anger away from those who actually wield power in British society.

To understand what today's establishment is and how it has changed, we have to go back to 1955: a Britain shaking off postwar austerity in favour of a new era of consumerism, rock'n'roll and Teddy Boys. But there was a more sinister side to the country, and it disturbed an ambitious Tory journalist in his early 30s named Henry Fairlie.

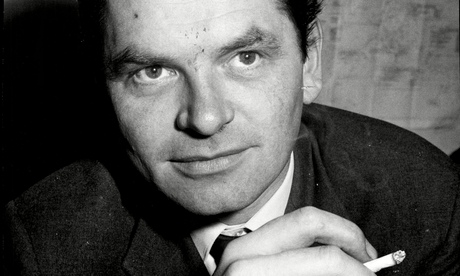

Henry Fairlie, the journalist who popularised the term 'the establishment' in the 1950s. Photograph: Associated Newspapers/Rex

Henry Fairlie, the journalist who popularised the term 'the establishment' in the 1950s. Photograph: Associated Newspapers/Rex

Early in his career, Fairlie was mixing with the powerful and the influential. In his 20s, he was already writing leader columns for the Times. But, at the age of 30, he left for the world of freelance writing and began penning a column for the Spectator magazine. Fairlie had grown cynical about the higher echelons of British society and, one day in the autumn of 1955, he wrote a piece explaining why. What attracted his attention was a scandal involving two Foreign Office officials, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, who had defected to the Soviet Union. Fairlie suggested that friends of the two men had attempted to shield their families from media attention.

This, he asserted, revealed that "what I call the 'establishment' in this country is today more powerful than ever before". His piece made "the establishment" a household phrase – and made Fairlie's name in the process.

For Fairlie, the establishment included not only "the centres of official power – though they are certainly part of it" – but "the whole matrix of official and social relations within which power is exercised".

This "exercise of power", he claimed, could only be understood as being "exercised socially". In other words, the establishment comprised a set of well-connected people who knew one another, mixed in the same circles and had one another's backs. It was not based on official, legal or formal arrangements, but rather on "subtle social relationships".

Fairlie's establishment consisted of a diverse network of people. It was not just the likes of the prime minister and the archbishop of Canterbury, but also incorporated "lesser mortals" such as the chairman of the Arts Council, the director general of the BBC and the editor of the Times Literary Supplement, "not to mention divinities like Lady Violet Bonham Carter" – the daughter of former Liberal prime minister Herbert Asquith, confidante of Winston Churchill and grandmother of future Hollywood actor Helena Bonham Carter.

The Foreign Office was, Fairlie claimed, "near the heart of the pattern of social relationships which so powerfully controls the exercise of power in this country", stacked as it was with those who "know all the right people". In other words, the establishment was all about "who you know".

But important facets of power in Britain were missing from Fairlie's definition. First, there was no reference to shared economic interests, the profound links that bring together the big-business, financial and political elites. Second, his piece gave no sense of a common mentality binding the establishment together. There was one – although it was very different from the mentality that dominates today, despite the fact that, then as now, an Old Etonian Conservative (Anthony Eden) was in Downing Street. For this was the era of welfare capitalism, and an ethos of statism and paternalism – above all, a belief that active government was necessary for a healthy, stable society – was shared by those with power.

The differences between Fairlie's era and our own show that Britain's ruling establishment is not static: the upper crust of British society has always been in a state of perpetual flux. This relentless change is driven by survival. History is littered with demands from below for ruling elites to give up some of their power, forcing members of the upper crust of British society to compromise. After all, unchecked obstinacy in the face of demands for change risks bringing down not just individual pillars of the establishment, but the entire system of power with them.

The monarchy is a striking example of a traditional pillar of power that, faced with occasionally formidable threats, has had to adapt to survive. This was evident right from the origins of a power-sharing arrangement between crown and parliament struck in the aftermath of revolution and foreign invasion in the 17th century, and which continues to exist today. Many of the monarchy's arbitrary powers, such as the ability to wage war, ended up in the hands of the prime minister. Even today, the monarchy's role is not entirely symbolic.

"The Crown is a bit of a vague institution, but it is kind of the heart of the constitution, where all the power comes from," says Andrew Child, campaign manager of Republic, a group advocating an elected head of state. The prime minister appoints and sacks government ministers without needing to consult the legislature or electorate because he is using the Queen's powers: these are the Crown's ministers, not the people's. In practice, too, members of the royal family have a powerful platform from which to intervene in democratic decisions.

Prince Charles, as next in line to the throne, has a powerful platform from which to intervene in democratic decisions. Photograph: Picasa

Prince Charles, as next in line to the throne, has a powerful platform from which to intervene in democratic decisions. Photograph: Picasa

Prince Charles, the designated successor to the throne, has met with ministers at least three dozen times since the 2010 general election and is known to have strong opinions on issues such as the environment, the hunting ban, "alternative" medicine and heritage.

In contrast to other European countries, Britain's aristocracy also managed to avoid obliteration by adapting and assimilating. In the wake of the industrial revolution it absorbed – much to the disgust of traditionalists – some prospering businessmen into its ranks, such as the City of London financier Lord Addington and the silk broker Lord Cheylesmore. The aristocracy continued to wield considerable political power throughout the 19th century, supplying many prime ministers, such as the 1st Duke of Wellington, the 2nd Earl Grey and the 2nd Viscount Melbourne. But following parliament acts passed by MPs in 1911 and 1949, this power was curtailed when the elected House of Commons enshrined in law its own dominance over the aristocrats' House of Lords. The legacy of centuries of aristocratic power has not vanished, though: more than a third of English and Welsh land – and more than 50% of rural land – remains in the hands of just 36,000 aristocrats.

Although less influential today than it has ever been, the Church of England retains the trappings of its old power. Indeed, the word establishment is testament to its one-time importance: the term is likely to derive from the fact that the Church of England is the country's "established church", or state religion, with the monarch serving as its head. The church's most senior official, the archbishop of Canterbury, is appointed by the prime minister on behalf of the monarch.

Even though Britain is one of the most irreligious countries on Earth, with just one in 10 attending church each week and a quarter of Britons having no religious beliefs, the Church of England still runs one in four primary and secondary schools in England, while its bishops sit in the House of Lords, making Britain the only country – other than Iran – to have automatically unelected clerics sitting in the legislature.

The establishment is a shape-shifter, evolving and adapting as needs must. But one thing that distinguishes today's establishment from earlier incarnations is its sense of triumphalism. The powerful once faced significant threats that kept them in check. But the opponents of our current establishment have, apparently, ceased to exist in any meaningful, organised way. Politicians largely conform to a similar script; once-mighty trade unions are now treated as if they have no legitimate place in political or even public life; and economists and academics who reject establishment ideology have been largely driven out of the intellectual mainstream. The end of the cold war was spun by politicians, intellectuals and the media to signal the death of any alternative to the status quo: "the end of history", as the US political scientist Francis Fukuyama put it. All this has left the establishment pushing at an open door. Whereas the position of the powerful was once undermined by the advent of democracy, an opposite process is now underway. The establishment is amassing wealth and aggressively annexing power in a way that has no precedent in modern times. After all, there is nothing to stop it.