Google’s search algorithm appears to be systematically promoting information that is either false or slanted with an extreme rightwing bias on subjects as varied as climate change and homosexuality.

Following a recent investigation by the Observer, which uncovered that Google’s search engine prominently suggests neo-Nazi websites and antisemitic writing, the Guardian has uncovered a dozen additional examples of biased search results.

Google’s search algorithm and its autocomplete function prioritize websites that, for example, declare that climate change is a hoax, being gay is a sin, and the Sandy Hook mass shooting never happened.

The increased scrutiny on the algorithms of Google – which removed antisemitic and sexist autocomplete phrases after the recent Observer investigation – comes at a time of tense debate surrounding the role of fake news in building support for conservative political leaders, particularly US President-elect Donald Trump.

Facebook has faced significant backlash for its role in enabling widespread dissemination of misinformation, and data scientists and communication experts have argued that rightwing groups have found creative ways to manipulate social media trends and search algorithms.

Google alters search autocomplete to remove 'are Jews evil' suggestion

The Guardian’s latest findings further suggest that Google’s searches are contributing to the problem.

In the past, when a journalist or academic exposes one of these algorithmic hiccups, humans at Google quietly make manual adjustments in a process that’s neither transparent nor accountable.

At the same time, politically motivated third parties including the ‘alt-right’, a far-right movement in the US, use a variety of techniques to trick the algorithm and push propaganda and misinformation higher up Google’s search rankings.

These insidious manipulations – both by Google and by third parties trying to game the system – impact how users of the search engine perceive the world, even influencing the way they vote. This has led some researchers to study Google’s role in the presidential election in the same way that they have scrutinized Facebook.

Robert Epstein from the American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology has spent four years trying to reverse engineer Google’s search algorithms. He believes, based on systematic research, that Google has the power to rig elections through something he calls the search engine manipulation effect (SEME).

Epstein conducted five experiments in two countries to find that biased rankings in search results can shift the opinions of undecided voters. If Google tweaks its algorithm to show more positive search results for a candidate, the searcher may form a more positive opinion of that candidate.

In September 2016, Epstein released findings, published through Russian news agency Sputnik News, that indicated Google had suppressed negative autocomplete search results relating to Hillary Clinton.

“We know that if there’s a negative autocomplete suggestion in the list, it will draw somewhere between five and 15 times as many clicks as a neutral suggestion,” Epstein said. “If you omit negatives for one perspective, one hotel chain or one candidate, you have a heck of a lot of people who are going to see only positive things for whatever the perspective you are supporting.”

Even changing the order in which certain search terms appear in the autocompleted list can make a huge impact, with the first result drawing the most clicks, he said.

At the time, Google said the autocomplete algorithm was designed to omit disparaging or offensive terms associated with individuals’ names but that it wasn’t an “exact science”.

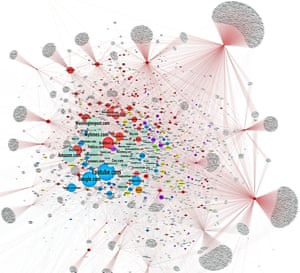

Then there’s the secret recipe of factors that feed into the algorithm Google uses to determine a web page’s importance – embedded with the biases of the humans who programmed it. These factors include how many and which other websites link to a page, how much traffic it receives, and how often a page is updated. People who are very active politically are typically the most partisan, which means that extremist views peddled actively on blogs and fringe media sites get elevated in the search ranking.

“These platforms are structured in such a way that they are allowing and enabling – consciously or unconsciously – more extreme views to dominate,” said Martin Moore from Kings College London’s Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power.

Appearing on the first page of Google search results can give websites with questionable editorial principles undue authority and traffic.

“These two manipulations can work together to have an enormous impact on people without their knowledge that they are being manipulated, and our research shows that very clearly,” Epstein said. “Virtually no one is aware of bias in search suggestions or rankings.”

This is compounded by Google’s personalization of search results, which means different users see different results based on their interests. “This gives companies like Google even more power to influence people’s opinions, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors,” he said.

Epstein wants Google to be more transparent about how and when it manually manipulates the algorithm.

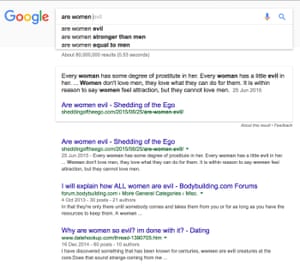

“They are constantly making these adjustments. It’s absurd for them to say everything is automated,” he said. Manual removals from autocomplete include “are jews evil” and “are women evil”. Google has also altered its results so when someone searches for ways to kill themselves they are shown a suicide helpline.

Shortly after Epstein released his research indicating the suppression of negative autocomplete search results relating to Clinton, which he credits to close ties between the Clinton campaign and Google, the search engine appeared to pull back from such censorship, he said. This, he argued, allowed for a flood of pro-Trump, anti-Clinton content (including fake news), some of which was created in retaliation to bubble to the top.

“If I had to do it over again I would not have released those data. There is some indication that they had an impact that was detrimental to Hillary Clinton, which was never my intention.”

Rhea Drysdale, the CEO of digital marketing company Outspoken Media, did not see evidence of pro-Clinton editing by Google. However, she did note networks of partisan websites – disproportionately rightwing – using much better search engine optimization techniques to ensure their worldview ranked highly.

Meanwhile, tech-savvy rightwing groups organized online and developed creative ways to control and manipulate social media conversations through mass actions, said Shane Burley, a journalist and researcher who has studied the alt-right.

“What happens is they can essentially jam hashtags so densely using multiple accounts, they end up making it trending,” he said. “That’s a great way for them to dictate how something is going to be covered, what’s going to be discussed. That’s helped them reframe the discussion of immigration.”

Burley noted that “cuckservative” – meaning conservatives who have sold out – is a good example of a term that the alt-right has managed to popularize in an effective way. Similarly if you search for “feminism is...” in Google, it autocompletes to “feminism is cancer”, a popular rallying cry for Trump supporters.

“It has this effect of making certain words kind of like magic words in search algorithms.”

The same groups – including members of the popular alt-right Reddit forum The_Donald – used techniques that are used by reputation management firms and marketers to push their companies up Google’s search results, to ensure pro-Trump imagery and articles ranked highly.

“Extremists have been trying to play Google’s algorithm for years, with varying degrees of success,” said Brittan Heller, director of technology and society at the Anti-Defamation League. “The key has traditionally been connected to influencing the algorithm with a high volume of biased search terms.”

The problem has become particularly challenging for Google in a post-truth era, where white supremacist websites may have the same indicator of “trustworthiness” in the eyes of Google as other websites high in the page rank.

“What does Google do when the lies aren’t the outliers any more?” Heller said.

“Previously there was the assumption that everything on the internet had a glimmer of truth about it. With the phenomenon of fake news and media hacking, that may be changing.”

A Google spokeswoman said in a statement: “We’ve received a lot of questions about autocomplete, and we want to help people understand how it works: Autocomplete predictions are algorithmically generated based on users’ search activity and interests. Users search for such a wide range of material on the web – 15% of searches we see every day are new. Because of this, terms that appear in Autocomplete may be unexpected or unpleasant. We do our best to prevent offensive terms, like porn and hate speech, from appearing, but we don’t always get it right. Autocomplete isn’t an exact science and we’re always working to improve our algorithms.”

Coca-Cola is among the companies named by Oxfam

Coca-Cola is among the companies named by Oxfam