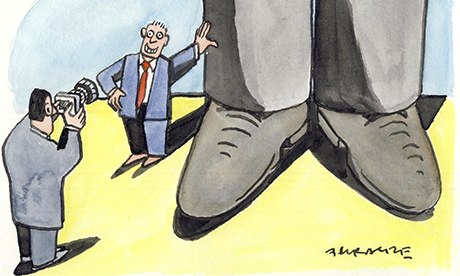

Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

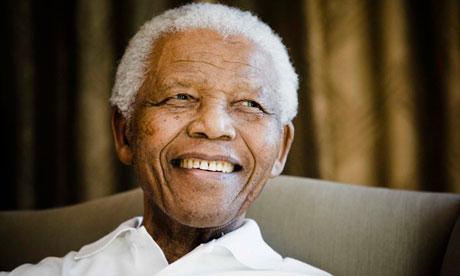

Asked for his feelings on meeting the Spice Girls in 1997 – shortly after Mel B had compared their "girl power quest" with the anti-apartheid movement – Nelson Mandela obliged. "I don't want to be emotional," he explained, "but this is one of the greatest moments of my life."

The twinkly-eyed gag was taken at face value by the group and plenty of dullard commentators, who were bemused, when they should simply have been amused. Mandela was a very funny man. In fact, every time I read the remark again I find myself laughing – not at Geri et al, which says something about how Mandela elevates even the cynical, but with him, who somehow contrived to tread the most elegant path through the unique absurdities of much of his later existence.

Less adroit, it must be said, are many of those lumbering to salute him in death – a global throng of Zeligs, from politicians to press, whose lifelong reverence for Mandela as a man and leader of a struggle was simply failed by the greatest superlatives. How on earth did apartheid endure so long, younger viewers may be wondering, considering everyone who was anyone seems to have been on Mandela's side?

"Nelson Mandela was a hero of our time," intoned David Cameron, who went off on a jolly to apartheid South Africa in 1989, with all expenses paid by a firm lobbying against sanctions. " President Mandela was one of the great forces for freedom and equality of our time," declared George W Bush, neglecting to mention that the ANC were still on a US terror-watch list until 2008, which meant the secretary of state had to certify that Mandela was not a terrorist in order for him to visit the country.

You have to laugh – mostly because that is probably what Mandela would have done. How often photos showed him roaring with laughter next to fawning leaders or dignitaries or whoever wanted a piece of him that day. I always imagined him getting the cosmic joke of it all – here he was, feted often by people who either couldn't have given a toss in his darkest times, or had transparently wished him ill.

Sainthood can be very sanitising, of course, and the right have a vested interest in smothering the realities of Mandela's radicalism under a lead blanket of tributes. But Mandela not only made history, he also did so in such a way that he made others wish to rewrite their own histories. In some cases, they seem to have done this because the argument against apartheid – and it actually was a matter of debate for plenty of people at the time, kids – was won so totally that to retrospectively admit in public that you were on the wrong side of it, or in effect on the fence, became akin to saying you were as politically witless as you were wicked.

Others have since discovered misty-eyed pasts. Not long ago, I asked Nigel Farage if Nelson Mandela was a political hero, on the basis that he has to be everyone's these days. "He's a human hero," the Ukip leader replied reverentially. "That day he came out of Robben Island" – it wasn't Robben Island, but anyway – "and stood there and forgave everybody, I just thought: 'This is Jesus.'"

Now, Farage was a rightwing Conservative activist in 1990, and doubtless it was uncharitable of me to think it odd that he should have thought about Mandela in those terms at that time, considering it would have been bizarrely uncharacteristic of his tribe (it wasn't awfully long after the Federation of Conservative Students used to wear Hang Mandela badges, while in the US the likes of Dick Cheney were voting against resolutions calling for his release). But more importantly, my scepticism – for which there was absolutely no evidence, I should say – was irrelevant. The point was that Farage believed he had thought that, and it is part of his personal folklore.

It's not just politicians, naturally. All self-respecting self-regarders jostled to touch Mandela's robe. At a 90th birthday party in London, Elton John sang a worshipful Happy Birthday to him – a track that presumably wasn't on the set list when Elton played Sun City in 1983. "My respects to an extraordinary person, probably one of the greatest humanists of our time," declared Thursday's tribute from Sepp Blatter, the man who demanded the frail elder statesman present himself at the World Cup final in South Africa, to the vocal distress of Mandela's family given he was mourning the tragic death of his 13-year-old great-granddaughter.

"Death of a colossus," was the headline in yesterday's Daily Mail, who marked his 1990 release with "The violent homecoming". "Violence and death disfigured the release of Nelson Mandela yesterday …" began that take on history.

They all came round in the end. Lesser people – minuscule folk such as myself, in fact – would occasionally have felt overwhelmed with the urge to inquire, even smilingly: "Well, where the hell were you when I was rotting in a cell for the best part of 30 years?" But in his superhuman magnanimity, Mandela never once mentioned it. So to follow his example in an infinitely smaller way, perhaps we should just roar with laughter ourselves at all the rightwing Mandela-venerators crawling out of the woodwork to weave themselves into his achievements. Such monumental progress could only be achieved by someone with the grace to understand a political reality: it is better that Johnny should come lately than not at all.