Statistics have long been argued one way or the other, but this government twists them beyond reality to suit its ruthless agenda

Illustration by Matt Kenyon

"Lies, damn lies and statistics," they say. "Torture a statistic enough and it will tell you anything," they say. Aphorisms that once sounded sound wry and urbane now make me want to set fire to things. I know, it is a risky old business, making a threat of arson, but I've already done it in an email, so this will hardly be news to GCHQ.

Worldwide, the era of post-truth politics began some time ago; during the last US elections, there were how-to guides for media outlets. "How does one evolve for the post-truth age?" asked the Atlantic, and it was a serious question. If you were trained in the "he-said, she-said" mode of reporting ("the chancellor says we are on the road to recovery; the shadow chancellor says, on the contrary, we are up shit creek with a baguette for a paddle") that will seem to you to be the fair and defensible way of doing things. If, however, one party starts to peddle a deliberate falsehood ("the chancellor says the deficit has gone down; the shadow chancellor says, on the contrary, the ONS figures show the deficit has gone up" – this is an example from real life, and happened on Tuesday), then the act of reporting both positions, in a tone of impartiality, serves to give them equal weight. Your neutrality shores up a lie.

-------

Also Read

Ministers who misuse statistics to mislead voters must pay the price

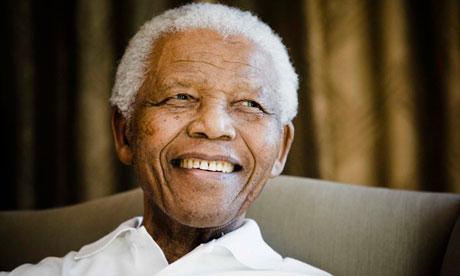

Lies, damned lies and Iain Duncan Smith

-------

This is for newshounds to tie themselves in knots over; I have never aimed at nor pretended impartiality. But I did prefer it when politicians, broadly speaking, told the truth. I have a pretty high tolerance for personal fibbing, who did and didn't have sex with whom, who was driving when the speed limit was broken. I don't enjoy, but I accept as the price of human variety, perspectives so different to mine that we exist in the orbit of extra-fact, our ideological magnets repelling one another so strongly that facts wouldn't help, because we'd never get close enough to jointly examine them (examples: Osborne on the Philpotts' benefits lifestyle; Hunt on the unaffordability of the NHS; Gove on most things). I used to get riled by the misuse of statistics, but at least that's done on the shared understanding that people should tell the truth in public life. A fact may turn out to have so much topspin that it isn't really true, but so long as the politicians have plausible deniability the contract isn't broken.

That deal is over. As Daniel Knowles of the Economist pointed out, more in impatience than in anger: "Over the last few months, as welfare cuts have started, questionable numbers have floated out of Iain Duncan Smith's office into the public debate like raw sewage." The protest group Disabled People Against Cuts collated 35 major untruths to emit from the government since 2010, and almost half of them came from IDS, who is well known to the (statistics) authorities, and has been reprimanded many times. If I were in charge, I would institute an asbo system in parliament; beyond a certain number of lies, MPs would have to sport a visible tattoo so that the casual onlooker would know to double-check their remarks.

The key things to watch with IDS are claims that the benefit cap is working; claims that the Work Programme is working; claims that the benefit system is rife with fraudsters; any claim about jobless households; most things he says about foreigners (with the caveat that if he is talking about a specific foreigner, José Mourinho or Angelina Jolie, it's likely that defamation laws will keep him on the straight and narrow); and everything he says about family breakdown.

But what chilled me most was the (relatively) minor lie, put about in November 2010, that private sector rents had fallen by 5% the previous year, while the amount paid by local authorities in housing benefit had gone up by 3% (Inside Housing analysed and rejected the claim). The clear implication was that people claiming the benefit were on the take – it was never said outright because it would have been functionally impossible (housing benefit is paid directly to the landlord); yet there it was, an impression hanging in the air, yet more craftiness from the feckless spongers.

David Cameron, meanwhile, has been reprimanded by the Office for Budget Responsibility (for lying about what it had said); and by the UK Statistics Authority for lying about the direction of the national debt (he said we were "paying it down", when in fact we were beefing it up). Osborne, besides lying this week about the deficit, has been reprimanded by the OBR (for lying about the nation's risk of bankruptcy) and by the UKSA. Amusingly, the Office for National Statistics was recently reprimanded by the UKSA for allowing the chancellor to pretend that a raid on the Bank of England's cash pile was equivalent to tax receipts. It's a carousel of meta-rebukes, as Osborne pulls ever more agencies into his circle of deliberate untruth.

There is a point on the spectrum of deceit at which the totally unprincipled, who will say anything to hold sway (I put Osborne in this category), meet the deeply religious, who are so sold on the notion of their own superiority that it is not necessary for reality to support them, merely for us all to be quiet, while they set us on the course of righteousness (and IDS in this one). But more important than any of their motives – there must, surely, be conservatives who would rather lose the argument than win it like this.