1. I'm a proctologist. (Proc·tol·o·gy n. The branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of disorders affecting the colon, rectum, and anus.)

2. "I'm unemployed since leaving prison. But I have applications in to be a bouncer at several whorehouses. Why do you ask?"

3. The Queen: "Oh. I ride around in the last horse-drawn carriage in England—and give tiny hand-waves. But the pay is good."

4. 'Work covered by official secrets act'

5. 'Model for a contraceptive products company'

6. 'Fiction writer for the police'

7. "It depends what day of the week it is"

8. Not a lot, but its how I do it that counts.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 8 March 2014

Discrimination UK style: Meet the professional refugees lucky to get the minimum wage in the UK

They were professionals in their own countries – lawyers, doctors, academics. Now, having fled and sought asylum in the UK, they're lucky if they can get a minimum-wage job. We meet six refugees adjusting to a very different way of life

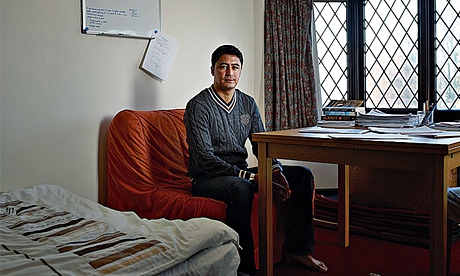

Wahid Ahmad: ‘The people I work with are very kind. They know I am an educated person.’ Photographs: David Emery for the Guardian

Wahid Ahmad, 33

Was: civil engineer, Afghanistan

Now: shelf stacker, north London

Now: shelf stacker, north London

Wahid Ahmad trained as a civil engineer in Afghanistan, where he worked in a senior role for the UN on infrastructure projects, overseeing road- and bridge-building. "I was proud of the job I was doing, helping with the development of my country," he says. It was a well-paid job and very satisfying: the new roads he worked on helped farmers get produce to the markets more quickly and children to school more safely. But his role working for an international agency attracted disapproving attention from the Taliban and after receiving a series of threats, in 2008 Ahmad fled to the UK with his wife and two children.

For six months, while his asylum application was being considered, Ahmad was not allowed to work. He studied to pass high-level English language exams, so he could take a one-year post-graduate certificate in construction management. While studying, he worked part-time in a cafe, making pizzas, kebabs and burgers, and delivering takeaway meals.

When he started applying for engineering jobs, he was so discouraged by the constant rejections that he was prescribed antidepressants. Most of the time he gets no response to his applications, just an automated email that tells him to assume his application has been unsuccessful if he hears nothing back within four days. When he calls to ask why, despite his excellent qualifications, he has not been invited for an interview, he is told he has no UK experience. At this point, he often proposes that he volunteers with the company, but the offer is always rejected. "How am I to get experience if they won't even let me volunteer?"

He took on a job in a food shop, working first as a halal butcher and later on the shop floor. "For a while it was very new to me. I would be preparing the fruit and vegetables, and it would keep coming to my mind what I was and what I am now. To be honest, it made me cry, but I have no option but to continue. The people I work with are very kind. They know I am an educated person. They tell me, 'Please don't be sad. You will find a job in your own field eventually.'"

He has been getting support from a charity, Transitions, which helped him work on his CV, try to get work experience and stay positive. On his CV, under the section detailing his civil engineering experience, he summarises the skills he has gained in his new job: "Be attentive to customers' needs; handle the payment for any purchases; make the customer aware of any special offers."

Iftikhar-ul-haq Khan, 46

Was: supreme court lawyer, Pakistan

Now: volunteer, Citizens Advice, Liverpool

Now: volunteer, Citizens Advice, Liverpool

In March 2010, Iftikhar-ul-haq Khan was dropping his children off at school when his car was stopped and he was kidnapped by a group hostile to the Ahmadiyya Muslim community to which he belongs. He was held for 19 days, in brutal conditions. As soon as he was released (upon the payment of a substantial ransom by his family), he made preparations to flee to England. It was clear to him that he and his wife and children would be in danger if they were to remain.

The transition was stark: "In Quetta, we had maids, a garden. We had a smooth life. In London, we shared one room in a bed and breakfast." It took almost two years before his asylum request was granted, during which time he was not allowed to work. "That was very difficult for me, particularly from a professional point of view." Once he was granted refugee status in October 2012 and began trying to find work, he was told that, without UK qualifications, his professional experience in Pakistan counted for little. "I was a legal adviser to the UN, to the National Bank of Pakistan." He worked on amending the Pakistan constitution and ran a private legal practice. To work here, he has to do an expensive legal conversion course. "After the course, I would need to start from scratch. People will still be asking what experience I have in this country. I achieved the highest level in my profession. Here I am at the beginning again."

The jobcentre is encouraging him to apply for work in the admin sector. "It feels a bit ridiculous. I had status, my own law firm, my profession. After three years here, I am in no man's land. I want to stand on my own two feet. I don't like being on benefits. I'm more used to helping others than taking help."

Khan has volunteered for Refugee Action and for the local Citizens Advice bureau. He enjoys it, but feels occasionally frustrated about the gulf between what he does now and what he once did. "I don't always think of myself as a supreme court lawyer. I try to give what I can. But sometimes it is in my mind that maybe I'm not doing the work I really should be doing."

His eldest daughter, 15, completed a two-year GCSE course in six months and got A*s, and a local newspaper interviewed her. "She made a contribution," Khan says. "We all want to give things back to this country. That makes me happy. I have no regrets. No complaints."

Agnes Tanoh, 57

Was: senior government adviser, Ivory Coast

Now: destitute asylum seeker, Birmingham

Now: destitute asylum seeker, Birmingham

Agnes Tanoh, former government adviser on financial and social affairs in Ivory Coast, fled her country because she faced arrest and long-term imprisonment, after regime change pushed her to the wrong side of the political divide. Before the government fell, she worked for the first lady, as her aide, then as head of her administration. Three years after fleeing to England, Tanoh has swapped a five-bedroom house in Abidjan for a flat paid for by the charity Women for Refugee Women in Birmingham. Her initial claim for asylum has been rejected, which means she has no entitlement to benefits and gets only £20 a week from the Hope Projects, a local asylum charity; £15.50 of that goes on her bus pass, which allows her to travel to language classes; she feeds herself by picking up basic supplies once a month from a food bank.

Most of her family have fled Ivory Coast; her husband of 33 years is in Ghana, her four children scattered in different countries. But for the moment, what makes her unhappy is the enforced idleness: the UK Border Agency stipulates, in emphatic capitals, in correspondence with her, "You are NOT allowed to work."

"Work is health," she says, taking off her glasses and rubbing her eyes. "I started working when I was 21. I am an active person. When you have nothing to do, you look on your situation and start to think. You say to yourself: 'What am I doing? What will become of me?'"

Although she is not a qualified teacher, in Ivory Coast she founded and ran a secondary school. For a while, when she was in a hostel in Bolton, she volunteered with a charity and taught French to retired people. "I enjoyed it a lot. I felt I was bringing something to people."

Hasan Abdalla, 58

Was: academic and artist, Syria

Now: jobseeker, London

Now: jobseeker, London

Hasan Abdalla had a well-equipped studio in the garden outside his Damascus flat; every morning he would walk past orange, apple, pear and pomegranate trees, to paint inside or in the open when the weather was fine. Now he paints in the bedroom of the south London bedsit where he has been living since he was granted asylum. It's much noisier, and he finds that the sounds from the Iceland loading station in front of the house and the railway tracks behind are often distracting. He has tried listening to music or singing to himself to drown out the noise, but on the whole it has been a difficult period for painting. He misses his wife and three sons, whom he hasn't seen since his hurried departure from Syria in July 2011. He finds London an inspirational place, but he also feels disoriented and alone.

Every stretch of wall in his small flat is covered with the artworks he managed to bring with him, and a few that he has done since arriving here. Beneath his bed he keeps rolled-up 3m canvases. The small kitchen table is covered with old newspaper, ready for him to start painting, but at the moment this happens rarely.

When you are dependent on jobseeker's allowance, painting is an expensive habit. In Syria, Abdalla regularly exhibited with two galleries, and made a good living from selling his work. But his reputation has not travelled with him, and although he has had pictures exhibited in three galleries here, he has sold very little. For three months he went by bus every Sunday to Bayswater Road, with as many paintings as he could carry, to try selling them on the park railings. It was a dispiriting experience, since the pictures got battered on the journey; and although passersby made appreciative comments, they rarely bought pictures.

In Syria and Libya, Abdalla sold his work for around £2,500. He has sold only four pictures since coming to England, each for a fraction of that price. Despite these difficulties, he knows that fleeing Syria, and paying an agent £20,000 of his savings, was the right thing to do. Two of his friends, who had been with him on a protest march in 2011, were shot by the authorities. He had spent time in prison in 2010, and been badly beaten. He was sacked from his job as a university lecturer because he failed security checks. Following his departure, his flat was searched and one of his sons arrested.

He has been supported by the Red Cross and thinks he is lucky to have ended up in England. "People are friendly. They try not to make you feel like a stranger."

Tiegisty Kibrom, 27

Was: IT graduate, Eritrea

Now: hotel cleaner, London

Now: hotel cleaner, London

Tiegisty Kibrom graduated with distinction in her computer science degree and hoped to open a computer business. "I wanted to have my own shop, which would be open for people who had no access to computers – I could train people on them. There's a real need for places like that in Eritrea."

She fled after being persecuted for her religious beliefs. When she was gone, her mother was arrested and held for three weeks. She thinks that it would not be safe to return.

With her excellent degree, she thought it would be easy to find work here, but when she realised how hard it would be to get a job, she enrolled on a BSc in internet computing at Manchester Metropolitan University. Even after completing the course, she has not found work in computing; last autumn she took a job cleaning rooms in a five-star hotel near Hyde Park. She works an evening shift, is responsible for cleaning 45 rooms and is paid £6.31 an hour. "I was expecting I'd get a better job. I am not ashamed to do a cleaning job. It just embarrasses me that, with all my skills, I can't find a single opportunity to work in my field." The work is hard. "Sometimes you feel abused. They say: 'If you don't do this, we will sack you.' I have enough stress in my life. They say: 'You know, girls, you have to be more grateful. Some people don't have any jobs.'"

She has volunteered as a computer instructor in a refugee centre; ultimately, she would like to be a database assistant, but mostly her job applications are not acknowledged. "I'm a fast learner, I know I could do it if they gave me a chance," she says.

Helal Attayee, 30

Was: doctor, Afghanistan

Now: healthcare assistant, London

Now: healthcare assistant, London

Before qualifying as a doctor, Helal Attayee worked for a US charity, Samaritan's Purse International Relief, as well as the British army and for the International Security Assistance Force as an interpreter and project manager in his home town, Mazar-i-Sharif.

He was repeatedly targeted by local fundamentalists, who branded him a traitor and threatened his family. He decided it would be safer to leave the country for his medical training, and went to Turkey. Once he had qualified, he returned to Afghanistan to work as a doctor, but quickly realised his life was at risk. "The local fundamentalists, who became Taliban later, told me that I was helping the infidels," Attayee says. "They warned me that I should stop."

He was forced to flee to the UK. He has been supported by the Red Cross while he studies for a number of exams he must pass before he can take up his old career, including a very demanding English exam. His English sounds flawless to me (as you would expect from a former UN interpreter), but he has failed the exam three times already. Each time he has to retake it, he has to pay £145. His bedroom, in a shared flat in north London, is filled with books and test papers, and ahead of his next test, he has covered a whiteboard on the wall with words that he finds challenging.

Attayee is currently working as a locum phlebotomist, taking blood for testing. "To become a doctor, you have to study for six or seven years," he says. "For phlebotomy, you just have to complete a four-day course. Anyone can do it. It was very, very difficult to find a job, so I was lucky,. Phlebotomy is fine. I know that it is only temporary."

A Primer on Sahara

Way back on August 31, 2012, the Supreme Court had asked Sahara group companies Sahara Housing Investment Corporation Ltd (SHICL) and Sahara Real Estate Corporation Ltd (SIRECL) to hand over Rs 24,029.73 crore to SEBI, with 15 per cent interest per annum from the date of receipt of the amount till the date of repayment, within a period of three months. SEBI was ordered to return the money after ascertaining the genuineness of each of the 2.96 crore investors and deposit the balance in the government revenue account.

- Sahara group only paid the first tranche of Rs 5,120 crore and defaulted in giving back the remaining amount. But they claimed in December 2012 that they had already paid off the investors Rs 22,885 crore. That is repayment within 4 months—in cash!

- The source of these 22885 crore—all cash—is a mystery that they wouldn't disclose even to the Supreme Court.

- If we add the accumulated interest, the total repayment from SAHARA would be 37000 crores.

- Earlier, they had claimed the deposits with them as private placement from 3.07 crores of friends, families, associates and employees! They first claimed that no general public was involved at all.

- Even before the SEBI case, when they first came under the RBI scanner, Sahara companies claimed to be dealing with small amounts deposited by millions of depositors. When the RBI revised the rules for Residual Non Banking Companies (RNBCs) and sought to control its para banking activities, Sahara claimed to haverepaid Rs 73000 crore, four years before maturity, and announced the same through ads. SEBI came into the picture when a Sahara group company filed a prospectus to go for a public issue of shares and the details included deposits raised by two other Sahara Companies.

- After the Supreme Court passed the order, Subrata Roy Sahara, in a full page ad, challenged SEBI for a national TV debate, to settle the matter!

- When the SEBI order was passed, depository accounts in India totalled 15 million. The largest company in India today has 4 million investors. Sahara claimed to have 30.7 million!

- The latest ad by Sahara talks about 80 million investors. India has about 250 million households. A third of India is below poverty line. That means every second household in India would be a Sahara investor.

- Based on investors details submitted by Sahara, SEBI sent out 21000 letters:

- Only 280 responded.

- 7000 letters were returned with addressee not found.

- The list of investors submitted to SEBI, on a cursory examination, included:

- 5984 Kalawatis

- 55 Kalawatis at the same address

- A Kalawati having the same address as a Mairunnissa, another investor

- A Kalawati being paid back on the same day multiple times

- 1433 Anirudh Singhs, all of them S/ O Hukum Singh

- One depositor's name was Haridwar.

- An address was Jaipur, Nagpur, Maharashtra.

- Another address was Aurangabad, Lucknow, UP.

- There are numerous instances of:

- one person having multiple accounts

- one account having multiple beneficiaries

- one person with multiple addresses

- one address having multiple investors.

- People whose claimed dues spread over multiple accounts running into crores.

- Many depositors addresses are untraceable,

- There were cases having addresses like national highways, and just names of villages with no specific house number etc.

- In SC, Saharas deposited a title deed of a 106 acre plot in Versova and claimed its worth at Rs.19300 Crores!! SEBI says it is not worth a penny, because it is in a mangrove and in a no construction zone.

- Sahara claims to employ 12 lakh employees. Applying the minimum Act Including PF, ESI, Bonus etc, the cost is 12500 per month. If i were to take different scales, the average would be 25000/month. That would be 36,000 Crores p.a of salaries alone!

- And the PF dues on such salaries would be about 5000 crores/annum. EPFO did ask for the details as they scarcely match with their records and Saharas go to Lucknow High Court and start another 'merry go round'.

- In an ad recently, they declared a 60% increment across the board. Wouldn't you love to work with them? As Rajnikanth would have said ''Any doubt'?

Questions for Narendra Modi

Reference AAM AADMI PARTY

1. If you become the PM, will you raise price of the KG Basin gas, which has already been doubled by the UPA government to $8 per unit?

2. Why does your government buy solar power at Rs 13 per unit? Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka are buying it at Rs 7.50 and Rs 5 per unit, respectively.

3. You claim 11% agriculture growth in state while your government's data says production has shrunk at 1.18% annually and revenue declined from Rs 27,815 crore in 2006-07 to Rs 25,908 crore in 2012-13. Why?

4. In the past 10 years, two-thirds of all SMEs have shut down in Gujarat, especially in your home town Mehsana where 140 units out of 187 died away. Do you want to concentrate all power in the hands of a few big industrial houses?

5. You claim to have eradicated corruption in Gujarat. People here claim that up to Rs 10 lakh bribe is demanded for appointment of a 'talati' (revenue official).

6. Your ministry has people like Babu Bokhiria, convicted for three years in a mining case, and Purshottam Solanki, accused in a Rs 450 crore fishing scandal. Why?

7. Why have you inducted in your cabinet a minister who is the son-in-law of the Ambani family?

8. About 13 lakh people applied for 1,500 posts of 'talati' recently. How can you claim to have solved the problem of unemployment?

9. Why is your government exploiting young graduates by paying them only Rs 5,300 per month for five years on contract basis?

10. There are only three teachers to teach 600 students at some schools. What is your comment?

11. Medical and health services are in a shambles.

12. Around 800 farmers have committed suicide in Gujarat in recent years because the government has stopped subsidies and is not paying support prices. Your reaction.

13. Electricity is a distant dream for four lakh farmers waiting for years to get a connection. Why do you claim 24x7 availability of electricity? Farmers have not been paid adequately for their land while the Ambanis and Adanis have got it for just one rupee per square metre.

14. Sardar Sarovar dam's height was raised in 2005 but people of Kutch have not got water. Industries have been given water. Why?

15. Despite assurances, the Gujarat government has not withdrawn court cases against Sikh farmers of Kutch who have lost their land. Why?

16. How many planes and helicopters do you have? Who owns them? How much do you pay or does someone else pay for them? Why don't you make public these air expenses?

1. If you become the PM, will you raise price of the KG Basin gas, which has already been doubled by the UPA government to $8 per unit?

2. Why does your government buy solar power at Rs 13 per unit? Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka are buying it at Rs 7.50 and Rs 5 per unit, respectively.

3. You claim 11% agriculture growth in state while your government's data says production has shrunk at 1.18% annually and revenue declined from Rs 27,815 crore in 2006-07 to Rs 25,908 crore in 2012-13. Why?

4. In the past 10 years, two-thirds of all SMEs have shut down in Gujarat, especially in your home town Mehsana where 140 units out of 187 died away. Do you want to concentrate all power in the hands of a few big industrial houses?

5. You claim to have eradicated corruption in Gujarat. People here claim that up to Rs 10 lakh bribe is demanded for appointment of a 'talati' (revenue official).

6. Your ministry has people like Babu Bokhiria, convicted for three years in a mining case, and Purshottam Solanki, accused in a Rs 450 crore fishing scandal. Why?

7. Why have you inducted in your cabinet a minister who is the son-in-law of the Ambani family?

8. About 13 lakh people applied for 1,500 posts of 'talati' recently. How can you claim to have solved the problem of unemployment?

9. Why is your government exploiting young graduates by paying them only Rs 5,300 per month for five years on contract basis?

10. There are only three teachers to teach 600 students at some schools. What is your comment?

11. Medical and health services are in a shambles.

12. Around 800 farmers have committed suicide in Gujarat in recent years because the government has stopped subsidies and is not paying support prices. Your reaction.

13. Electricity is a distant dream for four lakh farmers waiting for years to get a connection. Why do you claim 24x7 availability of electricity? Farmers have not been paid adequately for their land while the Ambanis and Adanis have got it for just one rupee per square metre.

14. Sardar Sarovar dam's height was raised in 2005 but people of Kutch have not got water. Industries have been given water. Why?

15. Despite assurances, the Gujarat government has not withdrawn court cases against Sikh farmers of Kutch who have lost their land. Why?

16. How many planes and helicopters do you have? Who owns them? How much do you pay or does someone else pay for them? Why don't you make public these air expenses?

Wednesday, 5 March 2014

India's activist role in breaking the pharmaceutical patent monopolies

Ritu Kumar in The Indian Express 4 March 2014

Recently, there were rumours that the United States Trade Representative (USTR) was getting ready to announce “trade enforcement actions” or sanctions against India over its intellectual property rights regime. The Obama administration has been under pressure from the US Chamber of Commerce and lobby groups, like the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, to take a tough stance against Indian rulings that have vetoed several multinational pharmaceutical company patents.

The lobbyists are pushing for India to be classified as a “priority foreign country”, a label associated with the worst offenders of patent law. The row blew over, but not before the USTR had filed a case at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) against India’s domestic content requirements for its solar programme.

In the last few years, the Indian government and judiciary have taken up major cases on patent protection for life-saving cancer drugs. Novartis’s drug Glivec was denied patent protection by the Supreme Court and India granted a compulsory licence to Bayer’s drug Nexavar, which treats kidney and liver cancer.

Compulsory licences are a provision in international patent norms, including the WTO’s TRIPS agreement, under which a government permits someone else to manufacture the patented product without the consent of the patent owner, usually to lower prices of life-saving drugs and increase access to them.

This is not the first time that India has taken a strong stance in the pharmaceutical patent wars. In 2001, Indian generic manufacturers played a crucial role in slashing prices of anti-retroviral (ARV) drugs used against HIV, bringing down the cost of the drugs per patient per year from around $15,000 to about $300. Today, the cost of ARV drugs is as low as $60 per patient per year. This remarkable achievement was only possible because at the time, India was not party to WTO agreements on patent protection.

Indian generic manufacturers were able to disregard patents, and ended up supplying over 80 per cent of all ARV drugs purchased in the world. India was recognised as playing a leading role in providing quality healthcare to people in developing countries.

It is evident that India’s role in the pharmaceutical patent wars has great implications for poor people’s access to healthcare, not just at home but around the world. Emerging economies like Brazil and South Africa follow the Indian model when they modify their intellectual property laws in order to bar awards to frivolous and obvious patents, and to allow pre-and post-grant challenges. For instance, Brazil’s proposed changes to its patent policy quote provisions in India’s Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005. Doctors Without Borders, meanwhile, has publicly encouraged South Africa to borrow from India when drafting its new patent policy.

With markets in the developed world becoming saturated, multinational drug companies are increasingly looking to emerging economies with large populations for sales expansion and growth. However, their model of intellectual property protection as an incentive for innovation is running into obstacles in low- and middle-income countries. Supporters of the pharmaceutical industry believe that without patent protections, there will be no breakthrough innovations and no new life-saving technologies.

They argue that the high costs of research and development for new drugs can only be compensated by patent monopolies that allow expensive drug prices. Yet, developing economies are keen on providing affordable healthcare products for their citizens. The developed world itself is beset with unsustainable rising healthcare costs and is looking for cost-effective innovation. A reassessment of patent monopolies, especially in the case of life-saving products, is essential if healthcare access is to be broadened beyond wealthy patients.

Some new models of incentivising medical research are being proposed. Since large funds are required for the development of new medical technologies, scholars have proposed the creation of attractive prizes, along the lines of the XPrize, which was instituted to encourage space exploration by giving successful teams up to $10 million in awards. The idea behind prizes is that the winning team receives a large one-time payment, but it cannot patent the solution, which ensures that the technology remains in the public domain.

Other models of funding innovation have already seen success in the marketplace, such as the public-private partnership that created a new rotavirus vaccine. This vaccine, called Rotavac, is now sold in India and other developing countries by Bharat Biotech, at profit, for about $1 per dose.

Millions of patients are suffering from many other poorly managed or untreatable diseases, such as diabetes or dengue fever. They would greatly benefit if companies were incentivised to create therapies at affordable prices that were widely accessible. India must not slow the pace of developing new therapies, nor shy away from the difficult work of making healthcare available to all. The rest of the world is watching.

For ‘cheering’ Pakistan in India match, university in Meerut suspends 67 Kashmiri students

Written by Amit Sharma , Mir Ehsan | Meerut | March 5, 2014 7:58 am in The Indian Express

A large private university in Meerut has suspended 67 Kashmiri students for allegedly cheering Pakistan during the India-Pak match at the Asia Cup on Sunday. The students were told to vacate their hostel rooms, and were escorted by police and university officials to nearby Ghaziabad. Some students are now back with their families in the Valley.

Groups of students were watching the match on TV in the community hall of the hostel at the Swami Vivekananda Subharti University (SVSU). A clash broke out soon after India lost, a result which the Kashmiris allegedly celebrated. No action was taken against the other group.

G S Bansal, the warden of the hostel, said the Kashmiri students had been punished for being “anti-national”. “By raising pro-Pakistan slogans, the Kashmiri boys did an anti-national act, and that was why we suspended them and did not take any action against the others,” Bansal told The Indian Express.

SVSU vice-chancellor Manzoor Ahmed said the suspension was a “precautionary measure”.

“There was strong resentment against the students who had shouted anti-national and pro-Pakistan slogans after Pakistan won the match. So as a precautionary measure, we temporarily suspended students of J&K for three days. We arranged for two buses to take the boys to Ghaziabad. We also sent three senior university officials with them,” Ahmed said.

Eyewitnesses said heated exchanges followed all-rounder Shahid Afridi’s last-over sixes off Ravichandran Ashwin, which quickly escalated to brawls, followed by several rounds of stone-throwing. “Security guards did not intervene for nearly an hour after the violence began. The students were ultimately forced to go to their rooms, but the groups clashed again on Monday,” said a student who spoke on condition of anonymity.

University registrar R K Garg said the students were sent home because the university feared more violence. “Meerut is communally sensitive. We were apprehensive that if word of the violence got out, outsiders would storm the campus and target students,” Garg said.

In Srinagar, families of the suspended students said they hoped for normalcy to return to the campus soon. “The university has ordered the students to leave for some time in order to avert confrontations between groups,” Abdul Majeed Khan of Uri said. Khan’s son is a second year student of BBA at the university. He added that the university administration had taken the right steps.

Shahid Bashir, whose son Talib Bashir had to leave Meerut, said, “The university has asked the students to leave for a few days. Most of the students have left for the Valley, while a few are staying in Delhi with friends. Once the situation improves, they will rejoin the university.”

Monday, 3 March 2014

Can the cricket coach be king?

The role is still evolving, but it's hard to see it become the centrepiece of the narrative like in football

Ed Smith in Cricinfo

March 3, 2014

| |||

Where is cricket's Jose Mourinho, its Pep Guardiola, its Sir Alex Ferguson?

I intend no disrespect to cricket coaches. But the question is unavoidable. The football manager has evolved not only as the boss - the "gaffer" - but also the central and controlling mind. He is the team's selector, its tactician and its figurehead. Compare cricket's separation of powers, a three-way division of responsibility. The selectors determine which players get onto the field; the captain sets the field, declares and changes the bowling; while the coach - well, hang on a minute, what does the coach do? This second question partly answers my first one: the role of the coach leads us to the absence of Jose Mourinho.

The original football manager was Herbert Chapman, whose first job was at Northampton Town in 1907. He pioneered a new style of play, rebranded his teams (it was Chapman who termed Arsenal "the Gunners"), and signed players at lower prices by plying rival directors with alcohol while he sipped ginger ale from a whisky glass. No wonder his nickname was "Football's Napoleon". That tradition of managerial control continues to this day. Arsenal's club captain is Thomas Vermaelen. You may not have noticed because he very rarely makes the team. The manager, Arsene Wenger, in contrast, is ever-present.

With occasional exceptions - meddling owners, egotistical chairmen, exceptional captains - there is no doubt who runs a football team: the manager. This has long made them the envy of the coaching fraternity. When the Welsh rugby visionary Carwyn James, who coached the British Lions, was asked if he had any regrets, he replied that he would have liked to be a football manager instead: they didn't have to put up with the interference of selectors.

Cricket didn't even have coaches when James was shaping his teams in the 1970s, let alone Chapman his in the 1910s. English cricket's first full-time professional coach was Micky Stewart, who took over as team manager for the 1986-87 tour of Australia. But Stewart and his generation of coaches were managers in name, not reality. They were more organisers than bosses. David Lloyd, who succeeded Stewart in the England job, put it like this: "The captain ruled the roost, he was the boss really, and you were there to support him. So I wouldn't cross either of the captains I worked with, Atherton or Stewart."

So history, clearly, is part of the explanation. The cricket coach is relatively new. There has not yet been much time for cricket's pioneering coaches to expand and enhance the role. One perfectly plausible projection is that cricket will become more like other sports and a single manager will assume control of the central decisions. Michael Vaughan believes that selectors are now superfluous and their role should been ceded to the coach. Sir Clive Woodward, who coached England to the rugby World Cup, recently accused cricket of being "stuck in the dark ages", with an over-mighty captain and a weak manager. Woodward was baffled that English cricket could sack Kevin Pietersen before the appointment of a new coach. Surely, Woodward argued, that decision was for the coach, not the captain and administrators? This line of argument holds that the cricket coach is still taking infant steps towards its logical evolution and that - in a decade or two - the coach will be king.

| A football coach can alter the effect of individual players by tinkering with the structure in which they operate. Cricket, in contrast, is the accumulation of what statisticians call "discrete" events, actions that occur in a comparative vacuum | |||

There is a counter argument. Ian Chappell and Shane Warne, among others, believe that the cricket coach should be held in check rather than allowed to launch a power grab. At international level, in Warne's words, "the coach shouldn't be coaching." The coach can certainly help create the right environment. But the Warne-Chappell approach remains suspicious of interventionist technical coaching once players have reached Test level. They believe it must be the captain, not the coach, who runs the team on the field.

This is the nub of the issue. Is there something about cricket, almost unique among sports, that makes it harder (perhaps impossible) for a coach to shape what happens during the match? We know it is the baseball manager who pulls off the pitcher and replaces him with a fresher arm. We know it is the football manager who devises the playing system and structure for each match. Why not cricket?

We now run into a parallel question: how central is captaincy? For if the coach wishes to become the defining figure, he can assume selection control from the selectors, but tactics he must wrestle from the captain. As a teenager, I was 12th man for Kent in a one-day match. I organised the drinks bottles while sitting next to the coach. When Kent took a wicket and I prepared to run onto the pitch, the coach pulled me to one side. "Tell the captain to change the bowling at the far end and move mid-off deeper. And tell him that has come from me!" I relayed the message. "Tell the coach to f*** off and let me captain the team," the captain replied, "and tell him that's from me." It was an early lesson in a familiar confusion about roles and responsibilities.

The structure of cricket may work against an off-field mastermind, certainly in the longer formats of the game. In a five-day match, the coach can only directly speak to his players at lunch, tea or the close of play. During each session, the captain must make his own decisions - as Bob Woolmer discovered when his coach-to-captain walkie-talkie system was outlawed in 1999. It is possible to imagine a T20 match mapped out in advance because there are only a small number of bowling changes to make. But a Test match is so fluid and unpredictable, with so many moving parts interacting and influencing each other, that a "planned" Test is a contradiction in terms.

In other respects cricket is anything but fluid. The ball is "live" in cricket for a very small percentage of the match. And for the vast majority of that time, only two or three players are involved: the bowler, the batsmen and sometimes a fielder. Crucially, their individual actions take place in perfect isolation. No one else can help you hit a cover drive or bowl a yorker. This truth is captured by the old cliché that cricket is a team game played by individuals.

That makes it very different from football. When an attacking player tracks back, the job of being a defender becomes fundamentally easier. When a coach devises a different midfield formation, the experience of being out on the pitch materially changes. The spaces are in different places, so it becomes a changed match. Not so in cricket. A coach (or captain) can change his batting order. But no coach can soften or alter the isolated examination that awaits all the batsmen when they eventually face Mitchell Johnson's thunderbolts. You can shuffle the pack, but the cards must be played individually.

This is the greatest challenge facing a cricket coach. A football coach can alter the effect of individual players by tinkering with the structure in which they operate. The presence of a good defensive midfielder frees up the playmaker to push up-field and express himself. Just ask the playmaker. When Real Madrid sold the defensive midfielder Claude Makelele and bought David Beckham instead, Zinedine Zidane felt the pinch. "Why put another layer of gold paint on the Bentley," asked Zidane, "when you are losing the entire engine?" These are managerial judgements, decisions about structure and strategy that affect almost every moment of a football match. Cricket, in contrast, is the accumulation of what statisticians call "discrete" events, actions that occur in a comparative vacuum.

Paradoxically, this makes it harder for cricket coaches to influence the shape of the match. They come up against an impenetrable wall: every player, with bat or ball, is on his own when it really matters. This, I suspect, is why cricket coaches, during periods of desperate failure, are so often reduced to the worst of all managerial failings: telling their players how to bat and bowl. It almost never works, but you can see how they end up there.

By my own logic, cricket coaching could evolve in either of two opposite directions. Given the technical and individual nature of the game, the trend may be towards individual coaches who work for the player, rather than vice versa - exactly as already happens in golf and tennis. Alternatively, cricket may eventually accept a version of the football model, despite its structural differences. One thing is certain. Unless that happens - and I'm not sure it should - I can't see a cricketing Jose Mourinho putting up with the constraints of the job. After all, pity the poor chief selector who relays the following message, "Jose, here's the team we've picked for you to play against Manchester City."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)