The

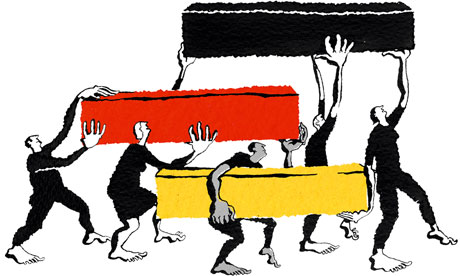

DOJ is making headlines with high-profile suits against Wall Street

firms, but singling out a few won't fix systemic wrongdoing

Standard & Poor's

faces a Department of Justice lawsuit alleging the firm succumbed to

conflicts of interest in their ratings for banks of mortgage-backed

securities. Photograph: Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images

In politics, public humiliation can often be a useful motivator.

Take the Department of Justice, which was hauled over the coals in a

recent PBS Frontline documentary on its lack of vigor in Wall Street prosecutions. The DOJ has been on a rampage lately.

The DOJ has been reportedly planning to file charges against the Royal Bank of Scotland, and last night, it filed an actual lawsuit against Standard & Poor's for misrating mortgage bonds before the financial crisis.

The Department of Justice is also getting creative and taking a novel tack. Standard & Poor's and other ratings firms have long maintained that their ratings, which were opinions, were protected under freedom of speech; in essence, you can't kill the messenger. This has proven a bulletproof defense for years.

The DOJ, in its lawsuit, counters that S&P acted as a double agent by allegedly violating its own standards. Ratings firms are paid by banks to rate products created by banks – an obvious conflict of interest in many cases. Standard & Poor's, like other firms, promised objectivity.

Thus the DOJ has alleged that S&P, while purporting to provide objectivity, was working on behalf of banks that needed good ratings for bad mortgage securities. To support this allegation, the DOJ quotes several emails that show S&P fretting over losing business to Moody's.

DOJ v Wall Street: from zero to hero

This rampage is great … directionally. The DOJ generally has to go crawling to Wall Street, tentatively striking deals that won't hurt financial reputations too badly and the bottom line hardly at all.

So, who doesn't love a major character finally overcoming its low self-esteem and owning its power?

In movie terms, this is the equivalent of the nerdy librarian who doffs her glasses and shakes out her hair, at which someone must yell, "Why, Miss Jones, you are magnificent!" It is Beyonce, pointedly filing her nails in the video for "Irreplaceable", squaring her shoulders and declaring, "You must not know about me. You got me twisted." It is Patrick Dempsey growing from spindly tween idol into a silvery heartthrob.

Considering that the DOJ is trying to regain its swagger, it seems churlish to object that it still may not be thinking big enough. And yet …

The DOJ's approach is great, in theory. It's good for a prosecutor's reputation to rake one firm over the coals and humiliate it publicly. But the truth is, the effect is limited. Other firms, rather than looking at the embarrassed firm and thinking, chastened, "there but for the grace of God go I," instead think, "God, glad I'm not like that poor sucker who got caught for doing what everyone does."

The DOJ is the greatest prosecutorial force in the country. It has subpoena power – excellent for commandeering embarrassing financial documents – and just enough resources and publicity power to really strike fear into Wall Street wrongdoers. The SEC is too underfunded; the CFTC has a shorter reach. The DOJ is, in short, the only entity in the country with any hope of accomplishing anything in the way of white-collar law enforcement.

Why 'making an example' doesn't work

There is some method to striking fear into the hearts of villains. For one thing, villains always believe they are exceptional. This is the case on Wall Street as well. Anyone who does anything dodgy involving money is usually pretty self-aware. He never deludes himself into thinking, "Oh, I am not doing anything wrong." He thinks, instead, "The authorities will never be smart enough to catch me."

This is why singling out RBS, or UBS, or S&P, will never have the fearsome deterrent effect that the DOJ really wants. In fact, by going after the firms piecemeal, the DOJ may actually be encouraging future wrongdoers rather than turning them away from crime.

You see, the DOJ is going after one or two firms for actions that were widespread across the industry. Fixing interest rates was the work of thousands of people. It's safe to say that S&P was not the only ratings firm that fretted that it would lose fees if it started downgrading bonds. In fact, S&P, according to the emails provided by the DOJ, frequently worried that it was not keeping up with Moody's.

This is a familiar pattern in Wall Street cases: Merrill Lynch, for instance, packaged all those bad mortgage securities partly because it was trying to outdo the profits of Goldman Sachs.

Wall Street's culture of rule-breaking

The dirty secret of Wall Street is that it delights in evading rules – not just for profit, but also for sport. To keep its skills sharp. The finance industry is full of clever people who love nothing more than finding loopholes to subvert authority, whether of government or of their own head of trading. The reason Wall Street leaders are always yelling about the necessity of teamwork is because acting mostly in one's individual self-interest – and the interest of one's bonus payment – is almost always the rule.

So, yes, this sudden burst of enthusiasm from the DOJ is a great development. There's no question that it's good, for most of the populace, to see one of America's great prosecutorial forces finally pull its act together on one of the defining scandals of our age: the greed – and sometimes fraud – that turned the housing crash into a financial crisis.

Yes, it's late – in fact, it pushes the traditional statute of limitations on such cases – but at least, some of the gears are finally moving. "Wisdom too often never comes, and so one ought not to reject it merely because it comes late," the supreme court Justice Felix Frankfurter once said, and he could have been talking about all these delayed actions.

It's also always fun to participate in the ritual of reading the hilariously self-incriminating internal emails that the DOJ captured. One of the best includes an S&P analyst sarcastically commenting that, after the crisis, the firm looked like something out of the 1980s hapless Wall Street comedy Trading Places:

Bond ratings now less relevant

Wall Street, of course, didn't need to see these emails to see which way the wind was blowing with the ratings firms. Most banks and trading floors stopped depending on official bond ratings ages ago, even though all the ratings firms retain excellent records on corporate and municipal bonds (in fact, anything that is not mortgage-related).

BlackRock, one of the favorite bond managers of the federal government, has boasted for years that it does its own analysis on potential defaults rather than rely on ratings firms. (BlackRock's founder, Larry Fink, was not coincidentally one of the creators of the mortgage-backed security.) Official ratings are often only a technical requirement, but rarely do many banks or investors rely on them any more – the same way those banks don't rely on the Libor interest rate any more.

Which is why the DOJ should cast its net wider. Ultimately, the DOJ lawsuit against S&P may make a splash, but it probably won't be a deterrent. The only thing that will do that is banks and investors forcing ratings firms to behave differently.

That's easy in times of calm, like now, but much harder in bubble times, when greed rules.

The DOJ has been reportedly planning to file charges against the Royal Bank of Scotland, and last night, it filed an actual lawsuit against Standard & Poor's for misrating mortgage bonds before the financial crisis.

The Department of Justice is also getting creative and taking a novel tack. Standard & Poor's and other ratings firms have long maintained that their ratings, which were opinions, were protected under freedom of speech; in essence, you can't kill the messenger. This has proven a bulletproof defense for years.

The DOJ, in its lawsuit, counters that S&P acted as a double agent by allegedly violating its own standards. Ratings firms are paid by banks to rate products created by banks – an obvious conflict of interest in many cases. Standard & Poor's, like other firms, promised objectivity.

Thus the DOJ has alleged that S&P, while purporting to provide objectivity, was working on behalf of banks that needed good ratings for bad mortgage securities. To support this allegation, the DOJ quotes several emails that show S&P fretting over losing business to Moody's.

DOJ v Wall Street: from zero to hero

This rampage is great … directionally. The DOJ generally has to go crawling to Wall Street, tentatively striking deals that won't hurt financial reputations too badly and the bottom line hardly at all.

So, who doesn't love a major character finally overcoming its low self-esteem and owning its power?

In movie terms, this is the equivalent of the nerdy librarian who doffs her glasses and shakes out her hair, at which someone must yell, "Why, Miss Jones, you are magnificent!" It is Beyonce, pointedly filing her nails in the video for "Irreplaceable", squaring her shoulders and declaring, "You must not know about me. You got me twisted." It is Patrick Dempsey growing from spindly tween idol into a silvery heartthrob.

Considering that the DOJ is trying to regain its swagger, it seems churlish to object that it still may not be thinking big enough. And yet …

The DOJ's approach is great, in theory. It's good for a prosecutor's reputation to rake one firm over the coals and humiliate it publicly. But the truth is, the effect is limited. Other firms, rather than looking at the embarrassed firm and thinking, chastened, "there but for the grace of God go I," instead think, "God, glad I'm not like that poor sucker who got caught for doing what everyone does."

The DOJ is the greatest prosecutorial force in the country. It has subpoena power – excellent for commandeering embarrassing financial documents – and just enough resources and publicity power to really strike fear into Wall Street wrongdoers. The SEC is too underfunded; the CFTC has a shorter reach. The DOJ is, in short, the only entity in the country with any hope of accomplishing anything in the way of white-collar law enforcement.

Why 'making an example' doesn't work

There is some method to striking fear into the hearts of villains. For one thing, villains always believe they are exceptional. This is the case on Wall Street as well. Anyone who does anything dodgy involving money is usually pretty self-aware. He never deludes himself into thinking, "Oh, I am not doing anything wrong." He thinks, instead, "The authorities will never be smart enough to catch me."

This is why singling out RBS, or UBS, or S&P, will never have the fearsome deterrent effect that the DOJ really wants. In fact, by going after the firms piecemeal, the DOJ may actually be encouraging future wrongdoers rather than turning them away from crime.

You see, the DOJ is going after one or two firms for actions that were widespread across the industry. Fixing interest rates was the work of thousands of people. It's safe to say that S&P was not the only ratings firm that fretted that it would lose fees if it started downgrading bonds. In fact, S&P, according to the emails provided by the DOJ, frequently worried that it was not keeping up with Moody's.

This is a familiar pattern in Wall Street cases: Merrill Lynch, for instance, packaged all those bad mortgage securities partly because it was trying to outdo the profits of Goldman Sachs.

Wall Street's culture of rule-breaking

The dirty secret of Wall Street is that it delights in evading rules – not just for profit, but also for sport. To keep its skills sharp. The finance industry is full of clever people who love nothing more than finding loopholes to subvert authority, whether of government or of their own head of trading. The reason Wall Street leaders are always yelling about the necessity of teamwork is because acting mostly in one's individual self-interest – and the interest of one's bonus payment – is almost always the rule.

So, yes, this sudden burst of enthusiasm from the DOJ is a great development. There's no question that it's good, for most of the populace, to see one of America's great prosecutorial forces finally pull its act together on one of the defining scandals of our age: the greed – and sometimes fraud – that turned the housing crash into a financial crisis.

Yes, it's late – in fact, it pushes the traditional statute of limitations on such cases – but at least, some of the gears are finally moving. "Wisdom too often never comes, and so one ought not to reject it merely because it comes late," the supreme court Justice Felix Frankfurter once said, and he could have been talking about all these delayed actions.

It's also always fun to participate in the ritual of reading the hilariously self-incriminating internal emails that the DOJ captured. One of the best includes an S&P analyst sarcastically commenting that, after the crisis, the firm looked like something out of the 1980s hapless Wall Street comedy Trading Places:

"You should see how it is here. It's like a friggin trading floor. 'Downgrade, Mortimer, downgrade!'"

Bond ratings now less relevant

Wall Street, of course, didn't need to see these emails to see which way the wind was blowing with the ratings firms. Most banks and trading floors stopped depending on official bond ratings ages ago, even though all the ratings firms retain excellent records on corporate and municipal bonds (in fact, anything that is not mortgage-related).

BlackRock, one of the favorite bond managers of the federal government, has boasted for years that it does its own analysis on potential defaults rather than rely on ratings firms. (BlackRock's founder, Larry Fink, was not coincidentally one of the creators of the mortgage-backed security.) Official ratings are often only a technical requirement, but rarely do many banks or investors rely on them any more – the same way those banks don't rely on the Libor interest rate any more.

Which is why the DOJ should cast its net wider. Ultimately, the DOJ lawsuit against S&P may make a splash, but it probably won't be a deterrent. The only thing that will do that is banks and investors forcing ratings firms to behave differently.

That's easy in times of calm, like now, but much harder in bubble times, when greed rules.