'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label dialogue. Show all posts

Showing posts with label dialogue. Show all posts

Monday, 15 January 2024

Monday, 6 December 2021

Thursday, 6 October 2016

PG Wodehouse's creative writing lessons

Sam Jordison in The Guardian

Anyone wanting to learn about plotting, not to mention prose perfection, should look to Leave it to Psmith's lean, absurd genius

Anyone wanting to learn about plotting, not to mention prose perfection, should look to Leave it to Psmith's lean, absurd genius

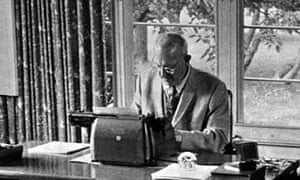

'I always feel the thing to go for is speed' … PG Wodehouse at his typewriter at his Long Island home in 1971. Photograph: AP

"I have been wondering where you would take this reading group for the book, although very enjoyable, isn't particularly nuanced or layered. What you read is all you get."

So wrote Reading group contributor AlanWSkinner wrote last week. I've been wondering too – worrying even. Leave It To Psmith offers plenty of delights. I laughed all the way through this story of impostors, jewel thieves and poets at Blandings Castle. But it's true that most of the novel's pleasures lie on the surface. AlanWSkinner may be right that there isn't much more than meets the eye. That's not a problem. But what scope does it leave for literary inquisition?

The truth is that I'd feel like I was attacking a soufflé with a pickaxe if I were to start hacking around for deep themes, dark images and political implications. Maybe it's possible to make something of the hilarious moral qualities Wodehouse ascribes to clothing. Why does he present Lord Emsworth "mould-stained and wearing a deplorable old jacket"? When we first meet Psmith, is it important that we are treated to the sight of "a very tall, very thin, very solemn young man, gleaming in a speckless top hat and a morning coat of irreproachable fit"? If this were Shakespeare I'd be looking for great significance in the similar descriptions that run throughout the book. But in Wodehouse, it just seems too much like over-explaining the joke, like attaching too much weight to an admirably light book. I think it's probably safest to assume that the only thing that really matters is that these sartorial notes are funny and help conjure up that magical inter-war world. Safe not least because burrowing any deeper would put us firmly into the camp of the poets and poseurs that Lady Constance Keeble has started to inflict on her poor old brother at Blandings Castle. And who wouldn't sympathise with Lord Emsworth when he declares: "Look here Connie … You know I hate literary fellows. It's bad enough having them in the house, but when it comes to having to go to London to fetch 'em … "

Fortunately, although I don't want to go deep, there are still things to say about Leave It To Psmith. For a start, that surface is covered in gems:

"The door opened, and Beach the butler entered, a dignified procession of one."

"My son Frederick," said Lord Emsworth, rather in the voice with which he would have called attention to the presence of a slug among his flowers."

"It contained a table with a red cloth, a chair, three stuffed birds in a glass case on the wall, and a small horsehair sofa. A depressing musty scent pervaded the place, as if a cheese had recently died there in painful circumstances. Eve gave a little shiver of distaste."

As the erstwhile editor of a series of books about Crap Towns, I also can't resist quoting the following description of the fictional Wallingford Street, West Kensington, at length:

"When the great revolution against London's ugliness really starts and yelling hordes of artists and architects, maddened beyond endurance, finally take the law into their own hands and rage through the city burning and destroying, Wallingford Street, West Kensington, will surely not escape the torch … Situated in the middle of one of those districts where London breaks out into a sort of eczema of red brick, it consists of two parallel rows of semi-detached villas, all exactly alike, each guarded by a ragged evergreen hedge, each with coloured glass of an extremely regrettable nature let into the panels of the front door; and sensitive young impressionists from the artists' colony up Holland Park way may sometimes be seen stumbling through it with hands over their eyes, muttering between clenched teeth 'How long? How long?'"

How wonderful to be in the presence of a master.

Such writing cannot be equalled. I wouldn't recommend that anyone should try. I'd also attempt to conceal from budding authors the horrifying information that Wodehouse wrote 40,000 words of this quality in just three weeks in 1922 and wrapped up the entire novel in a matter of months.

Otherwise, Leave It To Psmith should be compulsory reading for creative writing classes around the world. Especially when backed up by PG Wodehouse's own generous suggestions for a wannabe writer in a Paris Review interview given two years before his death in 1975 (a mere half-century after he wrote this novel) :

"I'd give him practical advice, and that is always get to the dialogue as soon as possible. I always feel the thing to go for is speed. Nothing puts the reader off more than a great slab of prose at the start."

In Leave It To Psmith the younger Wodehouse does just what his 91-year-old incarnation recommends. He hits the dialogue within a page of opening, and although many beautiful descriptions follow, a quick flick through suggests that there is never any more than a single page without some conversation. No danger of getting lost in details here.

In the same interview, he said:

"For a humorous novel you've got to have a scenario, and you've got to test it so that you know where the comedy comes in, where the situations come in … splitting it up into scenes (you can make a scene of almost anything) and have as little stuff in between as possible."

Again, it's all but impossible to find anything "in between". All the action takes place in clear, discrete scenes and each one leads to the other naturally and easily and with remarkable precision. It's lean. It's heading somewhere.

It almost didn't surprise me to learn that the book was successfully adapted for the stage during Wodehouse's lifetime. Almost. Because although the scenes are laid out as neatly as moody Blandings gardener Angus McAllister's flowerbeds, there's still a fiendish complexity behind them. Wodehouse also told The Paris Review:

"I think the success of every novel – if it's a novel of action – depends on the high spots. The thing to do is to say to yourself, '"Which are my big scenes?'' and then get every drop of juice out of them. The principle I always go on in writing a novel is to think of the characters in terms of actors in a play. I say to myself, if a big name were playing this part, and if he found that after a strong first act he had practically nothing to do in the second act, he would walk out. Now, then, can I twist the story so as to give him plenty to do all the way through?"

Yes, he thought about how things might work on the stage. But the crucial phrase here is "twist". The practical exercise I'd give to those lucky creative writing students would be to try to draw a schematic diagram of the plot of Leave It To Psmith, using coloured pencils, and, if they want to get really fancy, algebraic symbols for each of the characters and their movements. The resulting equations would be of fiendish complexity, there would be rainbows and arrows all over the place, leading to increasingly thick clumps where, with exquisite timing, Wodehouse has managed to land everyone in the same place at the right time. To give one quick example, the way in which he gets Psmith to Blandings Castle depends on at least three incredible coincidences, four or five bravura pieces of scene shifting that ensure Psmith lands in a chair opposite Lord Emsworth (and recently vacated by the Canadian poet Ralston McRodd) – not to mention a quite brilliant sleight of hand to enable Psmith to convince the Earl that he is the "Singer of Saskatoon" and expected at Blandings … And that's before he meets the Honourable Freddie Threepwood on a train and the plot really gets moving.

It's a masterpiece of timing and technique and the beautiful thing is, as a reader, you hardly even hear this intricate mechanism that Wodehouse has set ticking, so wonderful is everything else. There's a famous quote from VS Pritchett about his fellow Dulwich college alumnus: "The strength of Wodehouse lies not in his almost incomprehensibly intricate plots –Restoration comedy again – but in his prose style and there, above all, in his command of mind-splitting metaphor. To describe a girl as 'the sand in civilisation's spinach' enlarges and decorates the imagination."

I don't entirely agree. I think his plots are extraordinary. Few writers are better at moving characters around the board, even if few make them do sillier things. Their complexity is part of their charm and it's no surprise that Wodehouse said:

"It's the plots that I find so hard to work out. It takes such a long time to work one out."

What is surprising is that he then added:

"I like to think of some scene, it doesn't matter how crazy, and work backward and forward from it until eventually it becomes quite plausible and fits neatly into the story."

Plausible! That's almost as funny as his intentional jokes. The other delight of the Wodehouse plot is that it is almost entirely, gloriously absurd. But still. If you want to know how to construct a story, there are definitely worse places to look than Leave It To Psmith.

Where Pritchett is right, is in saying that the real glory of Wodehouse's scenarios lies in providing a platform for all his other talents. For getting Freddie Threepwood into a situation where he might propose to Eve Halliday by stating: "I say, I do think that you might marry a chap." For getting us all wondering what Ralston McTodd means when he invites us to look "across the pale parabola of joy". For sending Baxter tumbling down some stairs in a "Lucifer-like descent". For making, in short, this work of genius possible.

"I have been wondering where you would take this reading group for the book, although very enjoyable, isn't particularly nuanced or layered. What you read is all you get."

So wrote Reading group contributor AlanWSkinner wrote last week. I've been wondering too – worrying even. Leave It To Psmith offers plenty of delights. I laughed all the way through this story of impostors, jewel thieves and poets at Blandings Castle. But it's true that most of the novel's pleasures lie on the surface. AlanWSkinner may be right that there isn't much more than meets the eye. That's not a problem. But what scope does it leave for literary inquisition?

The truth is that I'd feel like I was attacking a soufflé with a pickaxe if I were to start hacking around for deep themes, dark images and political implications. Maybe it's possible to make something of the hilarious moral qualities Wodehouse ascribes to clothing. Why does he present Lord Emsworth "mould-stained and wearing a deplorable old jacket"? When we first meet Psmith, is it important that we are treated to the sight of "a very tall, very thin, very solemn young man, gleaming in a speckless top hat and a morning coat of irreproachable fit"? If this were Shakespeare I'd be looking for great significance in the similar descriptions that run throughout the book. But in Wodehouse, it just seems too much like over-explaining the joke, like attaching too much weight to an admirably light book. I think it's probably safest to assume that the only thing that really matters is that these sartorial notes are funny and help conjure up that magical inter-war world. Safe not least because burrowing any deeper would put us firmly into the camp of the poets and poseurs that Lady Constance Keeble has started to inflict on her poor old brother at Blandings Castle. And who wouldn't sympathise with Lord Emsworth when he declares: "Look here Connie … You know I hate literary fellows. It's bad enough having them in the house, but when it comes to having to go to London to fetch 'em … "

Fortunately, although I don't want to go deep, there are still things to say about Leave It To Psmith. For a start, that surface is covered in gems:

"The door opened, and Beach the butler entered, a dignified procession of one."

"My son Frederick," said Lord Emsworth, rather in the voice with which he would have called attention to the presence of a slug among his flowers."

"It contained a table with a red cloth, a chair, three stuffed birds in a glass case on the wall, and a small horsehair sofa. A depressing musty scent pervaded the place, as if a cheese had recently died there in painful circumstances. Eve gave a little shiver of distaste."

As the erstwhile editor of a series of books about Crap Towns, I also can't resist quoting the following description of the fictional Wallingford Street, West Kensington, at length:

"When the great revolution against London's ugliness really starts and yelling hordes of artists and architects, maddened beyond endurance, finally take the law into their own hands and rage through the city burning and destroying, Wallingford Street, West Kensington, will surely not escape the torch … Situated in the middle of one of those districts where London breaks out into a sort of eczema of red brick, it consists of two parallel rows of semi-detached villas, all exactly alike, each guarded by a ragged evergreen hedge, each with coloured glass of an extremely regrettable nature let into the panels of the front door; and sensitive young impressionists from the artists' colony up Holland Park way may sometimes be seen stumbling through it with hands over their eyes, muttering between clenched teeth 'How long? How long?'"

How wonderful to be in the presence of a master.

Such writing cannot be equalled. I wouldn't recommend that anyone should try. I'd also attempt to conceal from budding authors the horrifying information that Wodehouse wrote 40,000 words of this quality in just three weeks in 1922 and wrapped up the entire novel in a matter of months.

Otherwise, Leave It To Psmith should be compulsory reading for creative writing classes around the world. Especially when backed up by PG Wodehouse's own generous suggestions for a wannabe writer in a Paris Review interview given two years before his death in 1975 (a mere half-century after he wrote this novel) :

"I'd give him practical advice, and that is always get to the dialogue as soon as possible. I always feel the thing to go for is speed. Nothing puts the reader off more than a great slab of prose at the start."

In Leave It To Psmith the younger Wodehouse does just what his 91-year-old incarnation recommends. He hits the dialogue within a page of opening, and although many beautiful descriptions follow, a quick flick through suggests that there is never any more than a single page without some conversation. No danger of getting lost in details here.

In the same interview, he said:

"For a humorous novel you've got to have a scenario, and you've got to test it so that you know where the comedy comes in, where the situations come in … splitting it up into scenes (you can make a scene of almost anything) and have as little stuff in between as possible."

Again, it's all but impossible to find anything "in between". All the action takes place in clear, discrete scenes and each one leads to the other naturally and easily and with remarkable precision. It's lean. It's heading somewhere.

It almost didn't surprise me to learn that the book was successfully adapted for the stage during Wodehouse's lifetime. Almost. Because although the scenes are laid out as neatly as moody Blandings gardener Angus McAllister's flowerbeds, there's still a fiendish complexity behind them. Wodehouse also told The Paris Review:

"I think the success of every novel – if it's a novel of action – depends on the high spots. The thing to do is to say to yourself, '"Which are my big scenes?'' and then get every drop of juice out of them. The principle I always go on in writing a novel is to think of the characters in terms of actors in a play. I say to myself, if a big name were playing this part, and if he found that after a strong first act he had practically nothing to do in the second act, he would walk out. Now, then, can I twist the story so as to give him plenty to do all the way through?"

Yes, he thought about how things might work on the stage. But the crucial phrase here is "twist". The practical exercise I'd give to those lucky creative writing students would be to try to draw a schematic diagram of the plot of Leave It To Psmith, using coloured pencils, and, if they want to get really fancy, algebraic symbols for each of the characters and their movements. The resulting equations would be of fiendish complexity, there would be rainbows and arrows all over the place, leading to increasingly thick clumps where, with exquisite timing, Wodehouse has managed to land everyone in the same place at the right time. To give one quick example, the way in which he gets Psmith to Blandings Castle depends on at least three incredible coincidences, four or five bravura pieces of scene shifting that ensure Psmith lands in a chair opposite Lord Emsworth (and recently vacated by the Canadian poet Ralston McRodd) – not to mention a quite brilliant sleight of hand to enable Psmith to convince the Earl that he is the "Singer of Saskatoon" and expected at Blandings … And that's before he meets the Honourable Freddie Threepwood on a train and the plot really gets moving.

It's a masterpiece of timing and technique and the beautiful thing is, as a reader, you hardly even hear this intricate mechanism that Wodehouse has set ticking, so wonderful is everything else. There's a famous quote from VS Pritchett about his fellow Dulwich college alumnus: "The strength of Wodehouse lies not in his almost incomprehensibly intricate plots –Restoration comedy again – but in his prose style and there, above all, in his command of mind-splitting metaphor. To describe a girl as 'the sand in civilisation's spinach' enlarges and decorates the imagination."

I don't entirely agree. I think his plots are extraordinary. Few writers are better at moving characters around the board, even if few make them do sillier things. Their complexity is part of their charm and it's no surprise that Wodehouse said:

"It's the plots that I find so hard to work out. It takes such a long time to work one out."

What is surprising is that he then added:

"I like to think of some scene, it doesn't matter how crazy, and work backward and forward from it until eventually it becomes quite plausible and fits neatly into the story."

Plausible! That's almost as funny as his intentional jokes. The other delight of the Wodehouse plot is that it is almost entirely, gloriously absurd. But still. If you want to know how to construct a story, there are definitely worse places to look than Leave It To Psmith.

Where Pritchett is right, is in saying that the real glory of Wodehouse's scenarios lies in providing a platform for all his other talents. For getting Freddie Threepwood into a situation where he might propose to Eve Halliday by stating: "I say, I do think that you might marry a chap." For getting us all wondering what Ralston McTodd means when he invites us to look "across the pale parabola of joy". For sending Baxter tumbling down some stairs in a "Lucifer-like descent". For making, in short, this work of genius possible.

Thursday, 22 May 2014

How Modi defeated liberals like me

Shiv Visvanathan in The Hindu

What secularism did was it enforced oppositions in a way that the middle class felt apologetic and unconfident about its beliefs, its perspectives. Secularism was portrayed as an upwardly mobile, drawing room discourse they were inept at

On May 17, Narendra Modi revisited Varanasi to witness a pooja performed at the Kashi Vishwanath temple. After the ritual at the temple, he moved to Dashashwamedh ghat where an aarti was performed along the river. The aartiwas more than a spectacle. As a ritual, it echoed the great traditions of a city, as a performance it was riveting. As the event was relayed on TV, people messaged requesting that the event be shown in full, without commentary. Others claimed that this was the first time such a ritual was shown openly. With Mr. Modi around, the message claimed “We don’t need to be ashamed of our religion. This could not have happened earlier.”

At first the message irritated me and then made me thoughtful. A colleague of mine added, “You English speaking secularists have been utterly coercive, making the majority feel ashamed of what was natural.” The comment, though brutal and devastating, was fair. I realised at that moment that liberals like myself may be guilty of something deeper.

At the same time moment, some Leftists were downloading a complete set of National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) textbooks fearing that the advent of Mr. Modi may lead to the withdrawal of these books. The panic of some academics made them sound paranoid and brittle, positing a period of McCarthyism in India. It also brought into mind that both Right and Left have appealed to the state to determine what was correct history. With the advent of the Right, there is now a feeling that history will become another revolving door regime where the official and statist masquerade as the truth.

Secularism as a weapon

I am raising both sets of fear to understand why Left liberals failed to understand this election. Mr. Modi understood the anxieties of the middle class more acutely than the intellectuals. The Left intellectuals and their liberal siblings behaved as a club, snobbish about secularism, treating religion not as a way of life but as a superstition. It was this same group that tried to inject the idea of the scientific temper into the constitutions as if it would create immunity against religious fears and superstitions. By overemphasising secularism, they created an empty domain, a coercive milieu where ordinary people practising religion were seen as lesser orders of being.

I am raising both sets of fear to understand why Left liberals failed to understand this election. Mr. Modi understood the anxieties of the middle class more acutely than the intellectuals. The Left intellectuals and their liberal siblings behaved as a club, snobbish about secularism, treating religion not as a way of life but as a superstition. It was this same group that tried to inject the idea of the scientific temper into the constitutions as if it would create immunity against religious fears and superstitions. By overemphasising secularism, they created an empty domain, a coercive milieu where ordinary people practising religion were seen as lesser orders of being.

Secularism became a form of political correctness but sadly, in electoral India it became an invidious weapon. The regime used to placate minorities electorally, violating the majoritarian sense of fairness. In the choice between the parochialism of ethnicity and the secularism of citizenship, they veered toward ethnicity. It was a strange struggle between secularism as a form of piety or political correctness and people’s sense of religiosity, of the cosmic way religion impregnated the everydayness of their lives. The majority felt coerced by secular correctness which they saw either as empty or meaningless. Yet, they correctly felt that their syncretism was a better answer than secularism. Secularism gave one three options. The first was the separation from Church and State. This separation meant an equal distance from all religions or equal involvement in all religions. There was a sense that the constitution could uphold the first but as civilisations, as communities we were syncretic and conversational. One did not need a parliament of religions to be dialogic. Indian religions were perpetually dialogic. The dialogue of medical systems where practitioners compared their theologies, their theories and their therapies was one outstanding and constructive example.

There was a secondary separation between science and religion in the secular discourse. Yet oddly, it was Christianity that was continuously at odds with science while the great religions were always open to the sciences. Even this created a form of coerciveness, where even scientists open to religion or ritual were asked to distance themselves from it. The fuss made about a scientist coming to office after Rahukalam or even discouraging them from associating themselves with a godman like Sai Baba was like a tantrum. There is a sense of snobbery and poetry but more, there is an illiteracy here because religion, especially Christianity shaped the cosmologies of science. In many ways, Ecology is an attempt to reshape and reinvent that legacy.

Tapping into a ‘repression’

What secularism did was it enforced oppositions in a way that the middle class felt apologetic and unconfident about its beliefs, its perspectives. Secularism was portrayed as an upwardly mobile, drawing room discourse they were inept at. Secularism thus became a repression of the middle class. For the secularist, religion per se was taboo, permissible only when taught in a liberal arts or humanities class as poetry or metaphor. The secularist misunderstood religion and by creating a scientific piety, equated the religious with the communal. At one stroke a whole majority became ill at ease within its world views.

What secularism did was it enforced oppositions in a way that the middle class felt apologetic and unconfident about its beliefs, its perspectives. Secularism was portrayed as an upwardly mobile, drawing room discourse they were inept at. Secularism thus became a repression of the middle class. For the secularist, religion per se was taboo, permissible only when taught in a liberal arts or humanities class as poetry or metaphor. The secularist misunderstood religion and by creating a scientific piety, equated the religious with the communal. At one stroke a whole majority became ill at ease within its world views.

Narendra Modi sensed this unease, showed it was alienating and nursed that alienation. He turned the tables by showing secularism — rather than being a piety or a propriety — was a hypocrisy, or was becoming a staged unfairness which treated minority violations as superior to majoritarian prejudices. He showed that liberal secularism had become an Orwellian club where some prejudices were more equal than others. As the catchment area of the sullen, the coerced, and the repressed became huge, he had a middle class ready to battle the snobbery of the second rate Nehruvian elite. One sensitive case was conversion. The activism of Hindutva groups was treated as sinister but the fundamentalism of other religions was often treated as benign and as a minoritarian privilege. There was a failure of objectivity and fairness and the infelicitous term pseudo-secularism acquired a potency of its own.

While secularism was a modern theory, it was impatient in understanding the processes of being modern. Ours is a society where religion is simultaneously cosmology, ecology, ritual and metaphor. Most of us think and breathe through it. I remember a time when the epidemics of Ganesha statues were drinking milk. Hundreds of believers went to watch the phenomena and came away convinced. I remember talking to an office colleague who returned thrilled at what she had seen. I laughed cynically. She looked quietly and said, “I believe, I have faith, I saw it. You have no faith so why should the Murtitalk to you.” I realised that she felt that I was deprived. She added that the mahant of a temple where the statue had not drank milk had gone into exile and meditation to make up for his inadequacy. I realised at that moment that a lecture on hygroscopy or capillary action (the scientific explanations) would have been inadequate. I could not call her illiterate or superstitious. It was a struggle about different meanings, a juxtaposition of world views where she felt her religion gave her a meaning that my science could not. I was reminded that the great Danish physicist, Niels Bohr had a horseshoe nailed to his door. When Bohr was questioned about it, he commented that it won’t hurt to be there. Bohr had created a Pascalian Wager, content that if the horseshoe brought luck it was a good wager, but equally content that if it was inert it did no harm. I wish I had replied in a similar form to my friend.

For a pluralism of encounters

I realise that in many places in Europe, there has been a disenchantment with religion. I have seen beautiful churches in Holland become post offices as the church confronted a sheer lack of attendance. But India faces no such problem and we have to be careful about transplanting mechanical histories.

I realise that in many places in Europe, there has been a disenchantment with religion. I have seen beautiful churches in Holland become post offices as the church confronted a sheer lack of attendance. But India faces no such problem and we have to be careful about transplanting mechanical histories.

Ours is a different culture and it has responded to religion, myth and ritual. The beauty of our science Congress is that it resembles a miniature Kumbh Mela. But more, our religions have never been against science and our state has to work a more pluralistic understanding of these encounters. Secularism cannot be empty space. It has to create a pluralism of encounters and allow for levels of reality and interpretation. Tolerance is a weak form of secularism. In confronting the election, we have to reinvent secularism not as an apologetic or disciplinary space but as a playful dialogue. Only then can we offer an alternative to the resentments that Mr. Modi has thrived on and mobilised. I take hope in the words of one of my favourite scientists, the Dalai Lama. When George Bush was waxing eloquent about Muslims, the Dalai Lama commented on George Bush by saying, “He brings out the Muslim in me.” I think that captures my secular ethic brilliantly and one hopes such insights become a part of our contentious democracy.

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

Why the intellectual is on the run

Thanks to manufactured debates on TV, there is no time for irony and

nuance nor are we able to distinguish between a charlatan and an

academician

Harish Khare in The Hindu

Now that the Supreme Court has provided some sort of relief against harassment to Professor Ashis Nandy,

it has become incumbent upon all liberal voices to ponder over the

processes and arguments that combined to ensure that an eminent scholar

had to slink out of Jaipur in the middle of the night because of his

so-called controversial observations at a platform that was supposed to

be a celebration of ideas and imagination. Sensitive souls are quite

understandably dismayed; others have deplored the creeping culture of

intolerance. Some see the great sociologist as a victim of

overzealousness of identity politics. All this breast-beating is fine,

but we do need to ask ourselves as to what illiberal impulses and habits

are curdling up the intellectual’s space. We need to try to recognise

how and why Professor Nandy’s nuanced observations on a complex social

problem became “controversial.” Who deemed those remarks to be

“controversial?” And, these questions cannot be answered without

pointing out to the larger context of the current protocol of public

discourse — as also to note, regretfully, that the likes of Mr. Nandy

have themselves unwittingly countenanced these illiberal manners.

After all, this is not the first time — nor will it be the last — that a

sentence in a complex argument has been picked up to be thrashed out

into a controversy . This is now the only way we seem able to talk and

argue among ourselves. And we take pride in this descent into

unreasonableness. We are now fully addicted to the new culture of

controversy-manufacturing. We have gloriously succumbed to the

intoxicating notion that a controversy a day keeps the republic safe and

sound from the corrupt and corrosive “system.”

This happens every night. Ten or 15 words are taken out of a 3,000-word

essay or speech and made the basis of accusation and denunciation, as

part of our right to debate. We insistently perform these rituals of

denunciation and accusation as affirmation of our democratic

entitlement. Every night someone must be made to burn in the Fourth

Circle of Hell. In our nightly dance of aggression and snapping, touted

as the finest expression of civil society and its autonomy from the ugly

state and its uglier political minions, we turn our back on irony,

nuance and complexity and, instead, opt for angry bashing, respecting

neither office nor reputation. We are no longer able to distinguish

between a charlatan and an academician. A Mr. Nandy must be subjected to the same treatment as a Suresh Kalmadi.

Nandy, a collateral victim

Mr. Nandy’s discomfort is only a minor manifestation of this cultivated

bullishness. And let it be said that there is nothing personal against

him. He is simply a collateral victim of the new narrative genre in

which a “controversy” is to be contrived as a ‘grab-the-eyeballs’ game, a

game which is played out cynically and conceitedly for its own sake,

with no particular regard for any democratic fairness or intellectual

integrity. By now the narrative technique is very well-defined: a

“story” will not go off the air till an “apology” has been extracted on

camera and an “impact” is then flaunted. In this controversy-stoking

culture of bogus democratic ‘debate’, Mr. Nandy just happened to be

around on a slow day. Indeed it would be instructive to find out how

certain individuals were instigated to invoke the law against Mr. Nandy.

Perhaps the Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association needs to be

applauded for having the courage to call the Nandy controversy an

instance of “media violence.”

At any given time, it is the task of the intellectual to steer a society

and a nation away from moral uncertainties and cultural anxieties; it

is his mandate to discipline the mob, moderate its passions, disabuse it

of its prejudices, instil reasonableness, argue for sobriety and inject

enlightenment. It is not the intellectual’s job to give in to the mob’s

clamouring.

‘Middle class fundamentalism’

But, unfortunately, that is what our self-designated intellectuals have

reduced themselves to doing: getting overawed by television studio

warriors, allowing them to set the tone and tenor of dialogue. There is

now a new kind of fundamentalism — that of what is touted as the

“media-enabled middle class.” For this class of society, the heroes and

villains are well defined. Hence, the idea of debate is not to promote

understanding nor to seek middle ground nor to reason together, but to

bludgeon the reluctant into conformity. Mary McCarthy had once observed

that “to be continually on the attack is to run the risk of monotony …

and a greater risk is that of mechanical intolerance.”

When intellectuals and academicians like Ashis Nandy allow themselves to

be recruited to these “debates,” even if they are seen to be

articulating a dissenting point of view, their very presence and

participation lends credibility to the kangaroo courts of intimidation.

Manipulated voices

The so-called debate is controlled and manipulated and manufactured by

voices and groups without any democratic credentials or public

accountability. It would require an extraordinary leap of faith to

forget that powerful corporate interests have captured the sites of

freedom of speech and expressions; it would be a great public betrayal

to trust them as the sole custodians of abiding democratic values and

sentiments or promoters of public interest.

Intellectuals have connived with a culture of intolerance, accusation

and controversy-stoking that creates hysteria as an extreme form of

conformity. Every night with metronomic regularity our

discourse-overlords slap people with parking tickets.

And a controversy itself becomes a rationale for political response. Let

us recall how L.K. Advani was hounded out of the BJP leadership portals

because a “controversy” was created over his Jinnah speech. And, that

“controversy” was manufactured even before the text of the former deputy

prime minister’s Karachi remarks were available in India. Nor should we

forget how Jaswant Singh’s book on Jinnah was banned by the Gujarat

Chief Minister, Narendra Modi, even before it was published because our

newly designated national saviour had anticipated that a “controversy”

would get created.

The Nandy ordeal should also caution against the current itch to demand

“stringent” laws as a magical solution to all our complex social and

political ills like corruption. It would be sobering to keep in mind

that Mr. Nandy has been sought to be prosecuted under a stringent law

based on the formula of instant complaint, instant cognisance and

instant arrest. Mr. Nandy is lucky enough to have respected scholars

give him certificates of good conduct, testify that he is not a

“casteist” and that he is not against “reservation.” Lesser

intellectuals may not be that fortunate. We must learn to be a little

wary of our own good intentions and guard against righteous preachers.

If we insist on manufacturing controversy every day, all in the name of

giving vent to “anger”, it is only a matter of time before some sections

of society will be upset, angry and resort to violence. If we find

nothing wrong in manufacturing hysteria against Pakistan, or making wild

allegations against this or that public functionary, how can we object

to some group accusing Mr. Nandy of bias? When we do not invoke our

power of disapproval over Sushma Swaraj’s chillingly brutal demand for

“10 heads” of Pakistani soldiers, who will listen to us when we seek to

disapprove Mayawati’s demand for action against Mr. Nandy?

Just as the Delhi gang rape forced us to question and contest the

traditional complacency and conventions, the Ashis Nandy business will

be worth the trouble if it helps us wise up to the danger of culture of

bullishness and accusation. Unless we set out to reclaim the idea of

civilised dialogue, the intellectuals will continue to find themselves

on the run.

(Harish Khare is a veteran commentator and political analyst, and former media adviser to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh)

Monday, 21 January 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)