Courtney Martin in The Guardian

I spent Saturday morning at the public library with my 2.5-year-old daughter. She sat in the centre of a multi-racial, multi-lingual group of toddlers, spread her arms out as wide as they would go, and screamed: “He turned into a beautiful butterfly!” at the end of the consummate classic, The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The parents and grandparents giggled at the collective exuberance of little ones. The kids’ insanely spongy brains soaked up the sea of words surrounding them.

This may sound like a mundane scene, but it’s a surprising triumph for philanthropic equity – one of the few that exists at a meaningful, functional scale in our increasingly unequal country. At a time when early childhood has exploded as a lucrative market opportunity, no money is exchanged at the nation’s public libraries.

Why? Because in the 1850s, a wealthy guy invited a poor, 13-year-old immigrant boy to spend Saturday afternoons at his private library in Pittsburgh.

That boy grew up to be steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie rememberedthat, as a child, “I resolved, if wealth ever came to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries.” True to his word, Carnegie’s funding built about half of the 3,500 public libraries that existed by 1920.

Philanthropy has come a long way since the “Patron Saint of Libraries” took a childhood experience and turned it into a national legacy. Too often, it feels like we’ve lost our core wisdom about how change actually happens.

As they say, money can’t buy love. It can’t, ultimately, buy equity either. Both start with the seed of relationship.

There would be no three-year-old black kid in Oakland screaming hungry caterpillar exuberance without Andrew Carnegie. And there would no Andrew Carnegie without that Pittsburgh bibliophile.

So what does this mean for philanthropy? It means that the only philanthropy worth engaging in – both ethically and strategically speaking – is the kind that honours the wisdom of relationships and the power of money.

In what organiser and human rights activist Ella Baker deemed the “foundation complex” in 1963, those with money usually call the shots. Typically, a foundation positions itself as the expert and judges the merits of a nonprofit to solve a particular problem, whether it’s childhood hunger, or deforestation, or homelessness.

A girl stamping her own book at the old Aberystwyth Carnegie-funded public library, Wales. Photograph: Keith Morris/Alamy

I’ve been on the phone myself, scrambling to feel worthy of a foundation officer’s attention and money; nothing has inflicted me with a more toxic form of impostor syndrome. The questions foundation representatives ask, like those little bubbles on a standardised test, seem to pop up one after the other. With each one, I feel my breath get shallow. I’m feverishly tap-dancing when what I want to be doing is have good faith, meaningful conversation.

With individual donors, the hierarchy is often softened with social graces – a cup of coffee, a chat about shared passions, the scent of camaraderie – but ultimately the power dynamic is no different. One of us has the means and therefore is in the position of judging the other’s “good works”. In some ways, these interactions can be even more demoralising because they are deeply confusing; sometimes it can feel like you are performing friendship.

In the midst of particularly demoralising experiences with wealthy philanthropists, I have often reminded myself of my own privilege – a white woman from an upper-middle-class background with an Ivy League degree. If these interactions make me feel this way, imagine how confusing and alienating they likely are for people even further afield of the social class of most philanthropists.

A note about philanthropists’ demographics: three-fourths of foundations’ full-time staff are white and nearly 90% are over 30. Women flourish at smaller foundations – about three of four fundraisers are female – but at those with assets of more than $750m, women comprise only 28.9% of CEOs and CGOs (chief growth officers).

Board leadership is even more demographically starved. “Fully 85% of foundation board members are white, while just 7% are African American and only 4% are Hispanic,” said Gara LaMarche, president of the Democracy Alliance. “Nearly three-quarters of foundations have no written policy on board diversity, and fewer than 10% of board members are under 40.”

This means a lot of people who are not white, male and older are hustling their asses off to understand the sensibility of those who are. They are spending energy being tactical about how they talk about their work and build relationships, however transactional or tokenising. I admire their commitment and acuity, but even if some get good at translating and tap-dancing for dollars, that should not comfort the philanthropic world about its own inclusivity or transparency.

It only means that some people are willing to put in the work to get good at the game, not that the game isn’t profoundly rigged or that it doesn’t distract from getting real work done.

And the truth is, I imagine it’s a disconcerting experience for most philanthropists, too. On some level, they must know that they’re not the wisest authorities on the issues they’re seeking to effect. Money doesn’t make you an expert on poverty alleviation; in fact, it can make you dumber with distance. And yet, traditional philanthropy is set up to put you – the one with financial wealth – in the position of playing god with something you deeply care about. Even if it strokes your ego to be the decider, it’s got to erode your sense of integrity.

How can we reinvent philanthropy with an eye toward true equity? How can we create new cultures and structures that allow resources – financial, experiential, energetic – to flow in ways that feel dignifying? How do we create paradigm-shifting shit together, not just send LinkedIn requests and push money and paper around?

One obvious thing we can do is work to change the demographics of those giving away money and sitting on boards. But even that isn’t a fix; it’s a good bet to slowly shift culture, but not a promise of radical restructuring. There has been a slight uptick in black executives at foundations, for example, but as soon as they arrive, many are looking for an out, according to the Association of Black Foundation Executives. They overwhelmingly cite as their reason for fleeing that they want to be “more directly engaged in creating community change.” Duh.

If we really want to reinvent philanthropy then we are going to have to look at the underlying historic and structural causes of poverty and work to dismantle them and put new systems in their place. It’s also about culture – intentionally creating boundary-bashing friendships, learning to ask better, more generous questions, taking up less space.

It’s about what we are willing to acknowledge about the origins of our own wealth and privilege. It’s about reclaiming values that privilege often robs us of: first and foremost, humility. But also trust in the ingenuity and goodness of other people, particularly those without financial wealth. And a more accurate sense of proportion – where and how are philanthropists really most crucial in the fight for a more just society?

Several groups are working to show us what this kind of giving might look like. An example: a group of trust fund kids, calling themselves the Gulf South Allied Funders, took their own inheritances, raised even more money from their own networks and then donated the sum to the Twenty-First Century Foundation, which has a long-standing presence in New Orleans. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, they acknowledged their unfamiliarity with the community, and decided to funnel their resources to someone who could make a bigger difference.

Emergency response team volunteers clean up debris from a home destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. Photograph: Mark Humphrey/AP

Another: poor families in Boston and Detroit and Fresno track data about their own strengths and goals and then come together on a regular basis to talk about what they’re learning and the kinds of support they need. The families provide the moral support, while Family Independence Initiative provides the financial support in the form of scholarships, small business grants and other capital, on an as-needed basis.

And another: Self-Help, a family of nonprofit credit unions in North Carolina, California, and Florida, counter predatory lenders and high-fee check cashers in underserved communities by providing low-interest banking and loan services, financing community development projects and rehabilitating historic buildings with local partners. They celebrate the ways in which their current banking structure is significantly imprinted with the historic intelligence of African-American credit unions so critical during the Jim Crow era.

What makes these different than the average “foundation complex” experience? They have authentic, trusting relationships at the centre. They acknowledge history and local context. They walk their talk – moving beyond radical theory to radical practice.

To their credit, many of the world’s most powerful donors have begun to question the ethical underpinnings and best practicesof status quo philanthropy. In 2013,Peter Buffett, chairman of the NoVo Foundation, wrote a manifesto that, at its essence, was a call for more structural consciousness and less cognitive dissonance among wealthy altruists: “Because of who my father is, I’ve been able to occupy some seats I never expected to sit in. Inside any important philanthropy meeting, you witness heads of state meeting with investment managers and corporate leaders. All are searching for answers with their right hand to problems that others in the room have created with their left.”

More recently, Darren Walker, the President of the Ford Foundation, has called fora “new ‘gospel of wealth’ for the 21st century” – one that addresses “the underlying causes that perpetuate human suffering. In other words, philanthropy can no longer grapple simply with what is happening in the world, but also withhow and why.”

The shift in zeitgeist is promising. A critical mass of people working within philanthropy is hungry to do work with more ethical rigor; more systemic, cultural, and emotional intelligence; less bureaucracy and hubris. There is a growing conversation about these shifts. On paper, the will is there.

But philanthropists need more than “big ideas” about how their profession could and should change. They need radically new habits or these ideas just become bold in theory.

As Vu Le, the Executive Director of Rainier Valley Corps, points out: “True Equity takes time, energy, and thoughtfulness. It requires us to reexamine everything we know and change systems and practices that we have been using for hundreds of years. This is often painful and uncomfortable.”

In part, this is about scale. Philanthropists must push themselves to give more, and in particular, give more to address American poverty. Only 12% of total giving in 2015 went to “human services,” according to Giving USA. Wealthy donors are more likely to support the arts and higher education and less likely to give to social service charities, according to the Chronicle of Philanthropy. And they’re not as generous as those with less income: “The wealthiest Americans – those who earned $200,000 or more – reduced the share of income they gave to charity by 4.6% from 2006 to 2012. Meanwhile, Americans who earned less than $100,000 chipped in 4.5% more of their income during the same time period.”

In 2014, the poverty rate in the US reached 15%. Photograph: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

How and where do you meet potential grantees?

If you don’t have genuine relationships with those outside of your racial or class category, you’re going to have a hell of a time finding out about the most interesting, powerful work going on to tackle poverty.

How do you approach general operating funds or capital campaigns?

Have you ever noticed that foundations feel justified in spending millions on beautifully designed headquarters, but frown on nonprofits using money to spend a fraction of that on dignifying spaces of their own? Poor people, and those that partner with them, deserve fair salaries and beauty, too.

How can grant reporting be redesigned so it doesn’t create such huge frustration and a misuse of time and energy on the part of grantee organisations?

Human-centered design is so often heralded by foundations these days, but too often their own bureaucracies are filled with soul-deadening detail that is anything but humanising.

Do you build relationships for the long, systemic haul?

Funding also shapes and dictates our work by forcing us to conceptualise our communities as victimsAdjoa Florência Jones de Almeida, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded

Gara LaMarche takes his peers to task for talking big game about sustainability, but then essentially treating grantees like “the right wing would treat single mothers on welfare, imposing strict time limits and cutoffs – the fact is that most sustainability strategies are aimed at helping grantees move from dependency on one foundation to another.”

This may all seem “in the weeds”, but it has a huge impact of the daily lives of those tackling poverty on the ground. How we treat one another every day, as cliched as it may sound, becomes the nature of our relationships, and the nature of our relationships, becomes the nature of our institutions and, ultimately, systems.

Perhaps the most profound question that philanthropists can ask themselves at this ripe time for reinvention is this: what stories do you want or expect grantees to tell you? What stories do you tell about yourself?

Adjoa Florência Jones de Almeida of the Sista II Sista Collective in Brooklyn, NY,wrote in the groundbreaking anthology, The Revolution will not be Funded:

In theory, foundation funding provides us with the ability to do the work – it is supposed to facilitate what we do. But funding also shapes and dictates our work by forcing us to conceptualise our communities as victims. We are forced to talk about our members as being “disadvantaged” and “at risk”, and to highlight what we are doing to prevent them from getting pregnant or taking drugs – even when this is not, in essence, how we see them or the priority for our work.

Six years later, organiser and activist Mia Birdsong, took the TED stage and furthered the paradigm-shifting narrative: “The quarter-truths and limited plot lines have us convinced that poor people are a problem that needs fixing. What if we recognised that what’s working is the people and what’s broken is our approach?”

The story we’ve told about the poor in America, the story that we continue to ask them to tell in order to get funding, is that they’re broken. In fact, we are.

The ultimate irony of the way the philanthropic sector is structured is that it is actually the recipients – people of colour, the working class, women – that may be the most masterful at creating and maintaining long-lasting, catalytic relationships. They are disproportionately poor in terms of dollars and cents, but rich with experience of making a way out of no way and persevering in the face of huge, intractable, sometimes downright exploitative systems. This usually involves relying on friends and extended family, nurturing people’s gifts for the betterment of whole communities and having grace through challenge.

We have an ethical imperative to acknowledge and build new systems around that intelligence. Carnegie’s one ask of the public libraries that he funded, to be built in communities across the country, was that they each be engraved with an image of a rising sun and the words: “Let there be light.”

That light, for him, was present in books, but in truth, it was sparked by an unlikely relationship. Long-lasting change so often is.

Holly Baxter in The Independent

Watching the absurdity that is TrainGate unfold last night, I couldn’t help but feel that this was a real David and Goliath moment. Isn’t it nice when a billionaire tax-avoiding business magnate with a knighthood takes on a cruel and calculating powerhouse like Labour’s autocratically-minded leader of the opposition and wins? Isn’t it heartening to see the mainstream media take Richard Branson’s side for once, rather than deferring to the statements of a political figure who probably has lots to gain financially from the renationalisation of the railways? After all, it’s not like Branson, the owner of a private company that operates trains, would be affected by things like that. So I think we can all agree that, at the very least, his motives are pure and driven by a rigorous pursuit of objective justice and truth. As for Corbyn, who knows what devious schemes he could have up his sleeve once he’s allowed to hand control of some public transport back to the taxpayer? Isn’t that how Nazi Germany started?

As a born-and-bred Geordie who moved to London for university and stayed for work, I’ve taken the same Newcastle-bound train from London that Jeremy Corbyn sat on the floor of more times than I could count. In case anyone’s actually interested, I can categorically state that it was a lot more pleasant affair when East Coast Trains – the last nationalised arm of British railways – was running the show. The first thing that happened when it was sold off to Virgin was that prices went up and the loyalty scheme which allowed you to accrue points and use them to buy future journeys was stopped (it was replaced with a Nectar Points collaboration and a scheme that encourages you to collect Flying Club miles – two laughable air miles per £1 spent – which, you guessed it, can only be used on Virgin Atlantic planes).

Virgin might have released a press release (yes, for real) about Jeremy Corbyn’s journey this week, claiming that he’d find brilliantly cheap rail fares on their trains in future if he booked in advance, but the £120 return ticket to Durham that I bought weeks in advance for a friend’s wedding this weekend isn’t an anomaly. London to Durham is a journey of two and a half hours. The ridiculous fact that £90 is the cheapest I’ve ever seen a return ticket for it since Virgin took over speaks for itself.

Whether Corbyn sat on the floor to make a point, or because he didn’t look properly in all of the coaches for free seats, or because there were a couple of seats dotted about but he needed a few together for his team is immaterial to me. I’ve spent more than one Christmas Eve sitting curled up inside the luggage rack on the four-hour slow service back to my hometown because even the corridors are too packed to fit into, and I’ve paid extortionate amounts for the privilege. I know what Virgin Trains’ service on the east coast lines are like, even at their least crowded and their very best. A chirpy press release is, of course, going to talk up the “excellent offerings” available from London to Newcastle – but those people have never tried to eat one of their microwaved paninis or operate their on-board wifi, which, to put it kindly, exists more in the conceptual than the physical plane.

Privatised railways are a win for big businesses for obvious reasons: you can’t operate more than one train on one part of a railway line at one time; it’s not like selling a number of competing products together in a shop. Since new lines are hardly ever built, all a business really has to do is have enough money to buy up a monopoly on people’s journeys through whichever part of Britain it chooses. Then – hey presto! – guaranteed sky-high prices with the potential to increase exponentially, since your customer base has very little choice in the matter but to pay up or not travel at all. It’s a naturally uncompetitive business, which makes it a very good candidate for nationalisation and a very good profit-maker for companies with their eyes on the prize. Rail ticket prices, after all, go up like clockwork every year.

Astounded as I am by the fact that people have leapt on what is essentially one of the most boring political stories to have ever hit the headlines, I do support Corbyn’s policy of rail nationalisation in theory. Whether he sat on the floor and announced to camera that ram-packed trains are “a problem that many passengers face every day” as a publicity stunt or after only a half-hearted poke around for seats doesn’t concern me; the simple fact is that the statement is true.

What does concern me, however, is the way in which a discussion about one man sitting on the floor of a packed train has escalated into something which people are now referring to as TrainGate by anti-Corbyn factions, as if accidentally walking past a couple of unreserved seats on a train is genuinely comparable to one of modern America’s most controversial political scandals. I know this has been said a lot in the last few weeks, but really, Labour, have you lost your mind?

By David Robson in the BBC

Could you be fooled into “seeing” something that doesn’t exist?

Matthew Tompkins, a magician-turned-psychologist at the University of Oxford, has been investigating the ways that tricksters implant thoughts in people’s minds. With a masterful sleight of hand, he can make a poker chip disappear right in front of your eyes, or conjure a crayon out of thin air.

And finally, let’s watch the “phantom vanish trick”, which was the focus of his latest experiment:

What did he tuck into his fist? A red ball? A handkerchief?

Although interesting in themselves, the first three videos are really a warm-up for this more ambitious illusion, in which Tompkins tries to plant an image in the participant’s minds using the power of suggestion alone.

Around a third of his participants believed they had seen Tompkins take an object from the pot and tuck it into his hand – only to make it disappear later on. In fact, his fingers were always empty, but his clever pantomiming created an illusion of a real, visible object.

How is that possible? Psychologists have long known that the brain acts like an expert art restorer, touching up the rough images hitting our retina according to context and expectation. This “top-down processing” allows us to build a clear picture from the barest of details (such as this famous picture of the “Dalmatian in the snow”). It’s the reason we can make out a face in the dark, for instance. But occasionally, the brain may fill in too many of the gaps, allowing expectation to warp a picture so that it no longer reflects reality. In some ways, we really do see what we want to see.

This “top-down processing” is reflected in measures of brain activity, and it could easily explain the phantom vanish trick. The warm-up videos, the direction of his gaze, and his deft hand gestures all primed the participants’ brains to see the object between his fingers, and for some participants, this expectation overrode the reality in front of their eyes.

Lisa Wade in The Guardian

Moments before it happened, Cassidy, Jimena and Declan were sitting in the girls’ shared dorm room, casually chatting about what the cafeteria might be offering for dinner that night. They were just two weeks into their first year of college and looking forward to heading down to the meal hall – when suddenly Declan leaned over, grabbed the waist of Cassidy’s jeans, and pulled her crotch toward his face, proclaiming: “Dinner’s right here!”

Sitting on her lofted bunk bed, Jimena froze. Across the small room, Cassidy squealed with laughter, fell back onto her bed and helped Declan strip off her clothes. “What is happening!?” Jimena cried as Declan pushed his cargo shorts down and jumped under the covers with her roommate. “Sex is happening!” Cassidy said. It was four o’clock in the afternoon.

Cassidy and Declan proceeded to have sex, and Jimena turned to face her computer. When I asked her why she didn’t flee the room, she explained: “I was in shock.” Staying was strangely easier than leaving, she said, because the latter would have required her to turn her body toward the couple, climb out of her bunk, gather her stuff, and find the door, all with her eyes open. So, she waited it out, focusing on a television show played on her laptop in front of her, and catching reflected glimpses of Declan’s bobbing buttocks on her screen. That was the first time Cassidy had sex in front of her. By the third, she’d learned to read the signs and get out before it was too late.

'What is happening!?' Jimena cried. 'Sex is happening!' Cassidy said.

Cassidy and Jimena give us an idea of just how diverse college students’ attitudes toward sex can be. Jimena, a conservative, deeply religious child, was raised by her Nicaraguan immigrant parents to value modesty. Her parents told her, and she strongly believed, that “sex is a serious matter” and that bodies should be “respected, exalted, prized”. Though she didn’t intend to save her virginity for her wedding night, she couldn’t imagine anyone having sex in the absence of love.

Cassidy, an extroverted blond, grew up in a stuffy, mostly white, suburban neighborhood. She was eager to grasp the new freedoms that college offered and didn’t hesitate. On the day that she moved into their dorm, she narrated her Tinder chats aloud to Jimena as she looked to find a fellow student to hook up with. Later that evening she had sex with a match in his room, then went home and told Jimena everything. Jimena was “astounded” but, as would soon become clear, Cassidy was just warming up.

The cloisters at New College Oxford. Photograph: Alamy

Students like Cassidy have been hypervisible in news coverage of hookup culture, giving the impression that most college students are sexually adventurous. For years we’ve debated whether this is good or bad, only to discover, much to our surprise, that students aren’t having as much sex as we thought. In fact, they report the same number of sexual partners as their parents did at their age and are even more likely than previous generations to be what one set of scholars grimly refers to as “sexually inactive”.

One conclusion is to think that campus hookup culture is a myth, a tantalizing, panic-inducing, ultimately untrue story. But to think this is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is. It can’t be measured in sexual activity – whether high or low – because it’s not a behavior, it’s an ethos, an atmosphere, a milieu. A hookup culture is an environment that idealizes and promotes casual sexual encounters over other kinds, regardless of what students actually want or are doing. And it isn’t a myth at all.

I followed 101 students as part of the research for my book American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus. I invited students at two liberal arts schools to submit journals each week for a full semester, in which they wrote as much or as little as they liked about sex and romance on campus. The documents they submitted – varyingly rants, whispered gossip, critical analyses, protracted tales or simple streams of consciousness – came to over 1,500 single-spaced pages and exceeded a million words. To protect students’ confidentiality, I don’t use their real names or reveal the colleges they attend.

My read of these journals revealed four main categories of students. Cassidy and Declan were “enthusiasts”, students who enjoyed casual sex unequivocally. This 14% genuinely enjoyed hooking up and research suggests that they thrive. Jimena was as “abstainer”, one of the 34% who voluntary opted out in their first year. Another 8% abstained because they were in monogamous relationships. The remaining 45% were “dabblers”, students who were ambivalent about casual sex but succumbed to temptation, peer pressure or a sense of inevitability. Other more systematic quantitative research produces similar percentages.

These numbers show that students can opt out of hooking up, and many do. But my research makes clear that they can’t opt out of hookup culture. Whatever choice they make, it’s made meaningful in relationship to the culture. To participate gleefully, for example, is to be its standard bearer, even while being a numerical minority. To voluntarily abstain or commit to a monogamous relationship is to accept marginalization, to be seen as socially irrelevant and possibly sexually repressed. And to dabble is a way for students to bargain with hookup culture, accepting its terms in the hopes that it will deliver something they want.

Burke, for example, was a dabbler. He was strongly relationship-oriented, but his peers seemed to shun traditional dating. “It’s harder to ask someone out than it is to ask someone to go back to your room after fifteen minutes of chatting,” he observed wryly. He resisted hooking up, but “close quarters” made it “extremely easy” to occasionally fall into bed with people, especially when drunk. He always hoped his hookups would turn into something more – which is how most relationships form in hookup culture – but they never did.

‘To think that campus hookup culture is a myth … is to fundamentally misunderstand what hookup culture really is.’ Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

Wren dabbled, too. She identified as pansexual and had been hoping for a “queer haven” in college, but instead found it to be “quietly oppressive”. Her peers weren’t overtly homophobic and in classrooms they eagerly theorized queer sex, but at parties they “reverted back into gendered codes” and “masculine bullshit”. So she hooked up a little, but not as much as she would have liked.

My abstainers simply decided not to hook up at all. Some of these, like Jimena, were opposed to casual sex no matter the context, but most just weren’t interested in “hot”, “meaningless” sexual encounters. Sex in hookup culture isn’t just casual, it’s aggressively slapdash, excluding not just love, but also fondness and sometimes even basic courtesy.

Hookup culture prevails, even though it serves only a minority of students, because cultures don’t reflect what is, but a specific group’s vision of what should be. The students who are most likely to qualify as enthusiasts are also more likelythan other kinds of students to be affluent, able-bodied, white, conventionally attractive, heterosexual and male. These students know – whether consciously or not – that they can afford to take risks, protected by everything from social status to their parents’ pocketbooks.

Students who don’t carry these privileges, especially when they are disadvantaged in many different ways at once, are often pushed or pulled out of hooking up. One of my African American students, Jaslene, stated bluntly that hooking up isn’t “for black people”, referring specifically to a white standard of beauty for women that disadvantaged women like her in the erotic marketplace. She felt pushed out. Others pulled away. “Some of us with serious financial aid and grants,” said one of my students with an athletic scholarship, “tend to avoid high-risk situations”.

Hookup culture, then, isn’t what the majority of students want, it’s the privileging of the sexual lifestyle most strongly endorsed by those with the most power on campus, the same people we see privileged in every other part of American life. These students, as one Latina observed, “exude dominance”. On the quad, they’re boisterous and engage in loud greetings. They sunbathe and play catch on the green at the first sign of spring. At games, they paint their faces and sing fight songs. They use the campus as their playground. Their bodies – most often slim, athletic and well-dressed – convey an assured calm; they move among their peers with confidence and authority. Online, social media is saturated with their chatter and late night snapshots.

On big party nights, they fill residence halls with activity. Students who don’t party, who have no interest in hooking up, can’t help but know they’re there. “You can hear every conversation occurring in the hallway even with your door closed,” one of my abstainers reported. For hours she would listen to the “click-clacking of high heels” and exchanged reassurances of “Shut up! You look hot!” Eventually there would be a reprieve, but revelers always return drunker and louder.

The morning after, college cafeterias ring with a ritual retelling of the night before. Students who have nothing to contribute to these conversations are excluded just by virtue of having nothing to say. They perhaps eat at other tables, but the raised voices that come with excitement carry. At the gym, in classes, and at the library, flirtations lay the groundwork for the coming weekend. Hookup culture reaches into every corner of campus.

The conspicuousness of hookup culture’s most enthusiastic proponents makes it seem as if everyone is hooking up all the time. In one study students guessed that their peers were doing it 50 times a year, 25 times what the numbers actually show. In another, young men figured that 80% of college guys were having sex any given weekend. They would have been closer to the truth if they were guessing the percentage of men who’d ever had sex.

••

College students aren’t living up to their reputation and hookup culture is part of why. It offers only one kind of sexual experiment, a sexually hot, emotionally cold encounter that suits only a minority of students well. Those who dabble in it often find that their experiences are as mixed as their feelings. One-in-three students say that their sexual encounters have been “traumatic” or “very difficult to handle”. Almost two dozen studies have documented feelings of sexual regret,frustration, disappointment, distress and inadequacy. Many students decide, if hookups are their only option, they’d rather not have sex at all.

We’ve discovered that hookup culture isn’t the cause for concern that some once felt it was, but neither is it the utopia that others hoped. If the goal is to enable young people to learn about and share their sexualities in ways that help them grow to be healthy adults (if they want to explore at all), we’re not there yet. But the more we understand about hookup culture, the closer we’ll be able to get.

Richard P Grant in The Guardian

A video did the rounds a couple of years ago, of some self-styled “skeptic” disagreeing – robustly, shall we say – with an anti-vaxxer. The speaker was roundly cheered by everyone sharing the video – he sure put that idiot in their place!

Scientists love to argue. Cutting through bullshit and getting to the truth of the matter is pretty much the job description. So it’s not really surprising scientists and science supporters frequently take on those who dabble in homeopathy, or deny anthropogenic climate change, or who oppose vaccinations or genetically modified food.

It makes sense. You’ve got a population that is – on the whole – not scientifically literate, and you want to persuade them that they should be doing a and b (but not c) so that they/you/their children can have a better life.

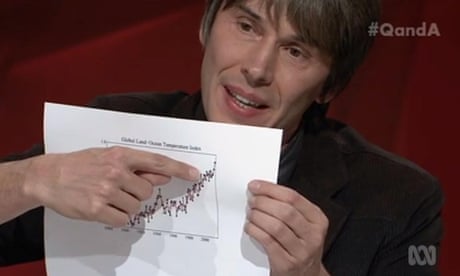

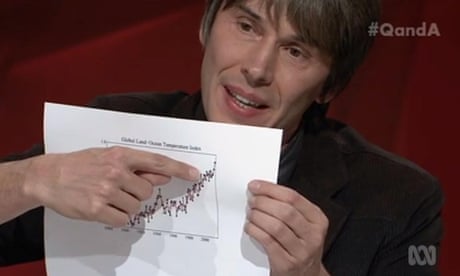

Brian Cox was at it last week, performing a “smackdown” on a climate change denier on the ABC’s Q&A discussion program. He brought graphs! Knockout blow.

Q&A smackdown: Brian Cox brings graphs to grapple with Malcolm Roberts

And yet … it leaves me cold. Is this really what science communication is about? Is this informing, changing minds, winning people over to a better, brighter future?

I doubt it somehow.

There are a couple of things here. And I don’t think it’s as simple as people rejecting science.

First, people don’t like being told what to do. This is part of what Michael Gove was driving at when he said people had had enough of experts. We rely on doctors and nurses to make us better, and on financial planners to help us invest. We expect scientists to research new cures for disease, or simply to find out how things work. We expect the government to try to do the best for most of the people most of the time, and weather forecasters to at least tell us what today was like even if they struggle with tomorrow.

But when these experts tell us how to live our lives – or even worse, what to think – something rebels. Especially when there is even the merest whiff of controversy or uncertainty. Back in your box, we say, and stick to what you’re good at.

We saw it in the recent referendum, we saw it when Dame Sally Davies said wine makes her think of breast cancer, and we saw it back in the late 1990s when the government of the time told people – who honestly, really wanted to do the best for their children – to shut up, stop asking questions and take the damn triple vaccine.

Which brings us to the second thing.

On the whole, I don’t think people who object to vaccines or GMOs are at heart anti-science. Some are, for sure, and these are the dangerous ones. But most people simply want to know that someone is listening, that someone is taking their worries seriously; that someone cares for them.

It’s more about who we are and our relationships than about what is right or true.

This is why, when you bring data to a TV show, you run the risk of appearing supercilious and judgemental. Even – especially – if you’re actually right.

People want to feel wanted and loved. That there is someone who will listen to them. To feel part of a family.

The physicist Sabine Hossenfelder gets this. Between contracts one time, she set up a “talk to a physicist” service. Fifty dollars gets you 20 minutes with a quantum physicist … who will listen to whatever crazy idea you have, and help you understand a little more about the world.

How many science communicators do you know who will take the time to listen to their audience? Who are willing to step outside their cosy little bubble and make an effort to reach people where they are, where they are confused and hurting; where they need?

Atul Gawande says scientists should assert “the true facts of good science” and expose the “bad science tactics that are being used to mislead people”. But that’s only part of the story, and is closing the barn door too late.

Because the charlatans have already recognised the need, and have built the communities that people crave. Tellingly, Gawande refers to the ‘scientific community’; and he’s absolutely right, there. Most science communication isn’t about persuading people; it’s self-affirmation for those already on the inside. Look at us, it says, aren’t we clever? We are exclusive, we are a gang, we are family.

That’s not communication. It’s not changing minds and it’s certainly not winning hearts and minds.

It’s tribalism.

Ben Chu in The Independent

Big numbers are all around us, shaping our political debates, influencing the way we think about things. For instance we hear a great deal about the prodigious size of the national debt: £1,603bn in July according to the latest official statistics.

There has been a proliferation of stories about the aggregate deficit of pension schemes, which has jumped to an estimated £1trn in the wake of the Brexit vote. And how could we forget that record net migration figure of 333,000, which figured so prominently in the recent European Union referendum campaign?

Yet there are other massive numbers we seldom hear about. The Office for National Statistics published some estimates for the “national balance sheet” last week. This is the place to look if you want really big numbers. They showed that the aggregate value of the UK’s residential housing stock in 2015 was £5.2 trillion – that’s up £350bn in just 12 months. A lot of people are a lot wealthier than they were a year ago.

That’s property wealth. What about the total value of households’ financial assets? According to the ONS, that stands at £6.2 trillion – up £113bn over the year. It will be even higher since the Brexit vote. Why? Because those ballooning pension scheme deficits we hear about represent a part of the financial assets of households.

Incidentally, a majority of the national debt, indirectly, represents a financial asset of UK households too. We often forget that for every financial liability there has to be a financial asset.

There’s still a good deal of handwringing in some quarters about the supposedly excessive borrowing of the state. But we don’t tend to hear anything about the debt of the corporate sector these days. The ONS reports that the total debt (loans and bonds combined) of British-based companies in 2015 was £1.35 trilion, pretty much where it was back in 2010.

If debt is something to get excited about, shouldn’t company borrowing be a cause for concern? Not, of course, if companies are borrowing to increase their productive capacities.

Actually, the major problem with corporate balance sheets lies in a different area. The ONS data shows that the corporate sector’s overall stocks of cash rose to £581bn in 2015, up £41bn on last year and a sum representing an astonishing 31 per cent of our GDP. It should be seriously worrying that firms are still choosing to keep so much cash on their balance sheets at a time when we badly need them to invest.

We tend to fret about the wrong big numbers. Consider the data on the liabilities of UK-based financial institutions. If you want a large number try this: £20.5 trillion. And around a quarter of these are financial derivative contracts. Many of those companies are foreign firms with UK operations. But UK banks – which we taxpayers still effectively underwrite because they are “too big to fail” – have aggregate liabilities worth £7.5 trillion.

That’s around four times larger than our GDP, yet Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, has rather strangely suggested he would be comfortable with that figure eventually rising to nine times national income.

Sometimes we fail to appreciate what lies behind the big numbers that shape our debates. The headlines this week said total UK employment grew by 172,000 in the three months to June. But this only tells one part of the story. Other data from the ONS showed that 478,000 people without jobs got them in the quarter, while 317,000 people entered the ranks of the unemployed. That headline figure is a net change in employment figure. And this wasn’t an unusually busy quarter for the jobs market.

This churn goes on constantly, with hundreds of thousands of us leaving jobs and hundreds of thousands taking new ones. The economic threat from the Brexit vote aftermath isn’t just people being made redundant – it’s a slowdown in hiring and that mighty labour market churn.

There’s a similar issue with those ubiquitous net migration figures. Newspapers talk of immigration creating “a new city the size of Newcastle each year” (or some variation on that line). That is rhetoric designed to stir public anxiety.

Yet that’s in context of an estimate of 36 million tourist visits to the UK each year, flows equal to half of the British population. And there are double the number of tourists visits going the other way each year.

What these big numbers emphasise is that we live in a mind-bendingly busy, complex and internationally connected economy. The figures we hear about, and which pundits fixate upon, are often the differences between two, or sometimes more, very large numbers. That bigger context should not be ignored.

The economic risks and fragilities of our economy are not always where we’re invited to believe they are.

Paul Mason in The Guardian

If you walk along Britain’s poorest streets, the phrase “left behind” – in vogue again after many such places voted to leave the EU – takes on a complex meaning. It’s not just that they are lagging behind the richer, better-connected places. It can seem, as you survey the pound stores and shuttered pubs, that these towns have been discarded: left behind, as in “unwanted on the journey”. Wealth has flowed out of them to somewhere else.

The logical question should be: who did this? Sometimes it’s obvious: in Ebbw Vale, for example, the answer is the Anglo-Dutch steel company Corus, which closed the plant in 2002. In many places it’s not obvious. Jobs seep away; council services are privatised; bus timetables dwindle; the local school gets taken over by a “superhead” from somewhere else, outsourcing the dinner ladies on day one. You can get angry about it, but there is nobody specific to be angry at.

Faced with the same problem, union and community organisers in the US have, in the past 12 months, adopted a novel way of fighting back. Through a campaign group called Hedge Clippers, they have begun tracing the lineages of financial power behind the decisions that affect specific places, and targeting those financiers – pension funds – with a new kind of pressure.

Steve Lerner, one of the instigators of the 1980s Justice for Janitors campaign, which, for the first time, organised migrant cleaning workers in the US, explains how the tactic evolved. “We were organising janitors working for contract cleaning companies: but they’re just middlemen,” he said. “So we targeted the building owners. It turned out they, too, were dependent on banks and pension companies, so we got a trillion dollars worth of pension money to say it won’t invest unless there is decent pay. Then we asked ourselves: OK, what else do they own?”

It turns out, quite a lot. In Baltimore, the city’s privatised water industry hiked its bills. Then, when people started to fall behind in payments, the city agreed to bundle up their unpaid bills into a financial vehicle called a “tax lien” and sell it to investors. The investors can, after two years, evict people from their homes for non-payment.

When campaigners looked at who was buying up the debt, they included an anonymous company linked to one of the biggest hedge funds in America: Fortress Investments, with $23bn worth of assets invested in “the largest pension funds, university endowments and foundations”.

Since the 2008 crisis, with returns on government bonds negative, and stock market dividends depressed, pension funds have been pouring money into the hedge fund sector. “It’s a form of assisted suicide,” Lerner argues: “Workers are investing their pension money into firms whose mission is to destroy us.”

He set up Hedge Clippers, which aims to force pension funds to divest from companies whose investment strategies fuel the cycle of impoverishment.

If you apply the same approach to Britain, you’re dealing with a different ecosystem. No city has yet securitised the unpaid debts of the poor, as Baltimore did. While there is no shortage of predatory lenders to the poor, there are – after a campaign led by Labour MP Stella Creasy – at least elementary controls on them.

However, pension funds are now the biggest source of money for UK hedge funds, according to a Financial Conduct Authority survey last year, with 43% of their money coming from institutional investors. The most obvious act of financial predation is the private finance initiative (PFI), where schools and hospitals were built with vastly lucrative private loans. As a result, the taxpayer is committed to paying back £232bn on assets worth £57bn.

Many pension funds, either directly or indirectly, are investing in the so-called “infrastructure funds” who buy up PFI debt. The investment analyst Preqin found 588 institutional investors worldwide with “a preference for funds targeting PFI”, 40% of which were based in Europe.

Tracing the more complex ways institutional finance is funding the cycle of impoverishment is not easy. What you would want to know, in places such as Stoke-on-Trent or Newport, is not just who took the decisions to close high-value workplaces but, more importantly, who makes the decisions that lead to chronic under-investment now. Governments, including the devolved ones of the UK, spend a lot of time and money effectively bribing global companies to create jobs and keep them in Britain’s depressed areas. Communities themselves have little or no input into the process, which is in any case all carrot and no stick.

Lerner’s initiative in the US grew out of trade union activism, because the unions there learned to follow the money instead of wasting time trying to negotiate with the powerless underlings of global finance. They worked out that, in an age where the workplace and the community can seem like two different spheres of activism, it is the finance system that links the two.

Older ‘left-behind’ voters turned against a political class with values opposed to theirs

Union organising of the unorganised, and community activism in Britain have both traditionally been weak because top-down Labourism has been strong. Faced with PFI, predatory loans, rip-off landlords and privatisation, the British way is to demand legislation, not chain yourself to the door of a Mayfair hedge fund.

With or without Jeremy Corbyn, the near-impossibility of Labour gaining a Commons majority in 2020 – whether because of Scotland, boundary changes, a hostile media or self-destruction – has to refocus the left on to what is possible to achieve from below. We have to start, as the Americans did, by mapping the invisible forces that strip jobs, value and hope out of communities; make them visible; trace their dependencies and then use direct action to kick them in the corporate goolies until they desist.