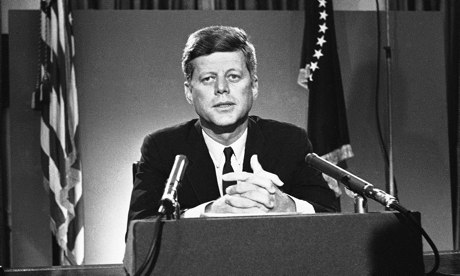

'If you were pushing anyone who couldn’t walk but wasn’t a baby, people would happily put themselves out a bit.' Photograph: Rex Features/J.Norden/IBL

Dr Aric Sigman, at a conference convened by Mothers At Home Matter (if you want a clue, as to its agenda, I refer you to the name), warned of the rise of "motherism"; a prejudice against stay-at-home mothers. Sigman is well known for his re-traditionalising intentions, to which end he has been accused of misrepresenting behavioural and neurological evidence, a charge he has denied. So, he says "motherism" is dangerous because it puts women off being stay-at-home mothers, which is the developmental ideal. I'd reject the second part of the argument, but not the first – there is a prejudice against stay-at-home mothers. There is a presentation of women who look after their own children full time as air-headed, spoilt and dowdy. However, there is also a prejudice against women who look after their children but aren't dowdy (yummy mummies); women who go back to work after having had children; women who stay out of work but also employ nannies; women who work part-time and look after their children the rest of the time.

I think the only way you could gain approval for your time-management, as a mother, would be to look after your children all the time as well as working full-time but for some socially useful enterprise (ideally voluntary work), while never relying on a man for money, yet never claiming benefits either, but God forbid that you should have a private income. Mothers in society act as whipping boys for almost all other social fissures; oh, the irony of there being no female equivalent for the phrase "whipping boy", when it is almost always a female. Oh the side-spitting irony. Here are four examples of "motherisms" at work:

1) What they say: "I don't see why mothers need these enormous buggies"

If you were pushing anyone who couldn't walk but wasn't a baby, people would happily put themselves out a bit. The act of pushing a baby, however, confers an aura of smugness about you ("look at you, so in love, with your baby") that makes it unthinkable to just help you out. There's an element of sense in this; mothers are in love with their babies, for the most part. And they would see you step into a puddle just to avoid the smallest jolt to their airsprung sleeping chariot. But it's not the end of the sodding world, is it, mothers temporarily losing their social etiquette while they fall in love with their babies?

2. What they say (at the school gates, whispered): "You never see the mother"

Even if the child is dropped off by the father, there is very little quarter given to the mother who isn't visible to the child's social circle, and not much consideration of the possibility that maybe her work starts at 9am precisely so she can get home by 6pm. I personally think this is a Freudian throwback, the resentment of children of the 70s and 80s, who were the first generation having to contend with bloody maternal no-shows at the harvest festival. It's the only rationale I can think of for why a person would think it was any of their business how a mother organised her time.

3. What they say (going in to a cafe, during the hours of standard economic activity): 'Look at all these women who don't work. I wish I could afford not to work'

I personally think the greatest misconception around childcare, shared by a huge proportion of the adult population, the people who've never done it, plus people who've done it but can't remember it, is that it is easy. It is by far the most demanding job conceived by society, wringing you out like a blood-drenched bedsheet, each day leaving you physically drained and mentally poleaxed, without even the energy to close your own mouth or hold your head upright, often making an involuntary gargling noise. Some of it's quite fun. But anyway, that's an aside. There's no economic sense to this question; if the women drinking coffee weren't looking after their children, someone else would have to, which would in most cases cost as much as their wages. So what people are really objecting to is not that mothers can afford not to work, but that they can still afford coffee.

4. What they say: 'I never have anything to say to these yummy mummies'

Dressed up as a deficiency of the speaker (I never have anything to say) it is actually a charge levelled at the mother, that she has no interests; why? Because, being "yummy", she is narcissistic and can't see beyond pilates and Brazilian hot waxing. The true resentment is of her wealth – that her life isn't one of drudgery and servitude, but spa treatments and interiors. Well, that's fine – it's possible to make a good case for objecting to wealth, since so much of it is unjustly come by. But at least object to the people unjustly coming by it. It seems a little tangential to make the wife the object of the opprobrium. All she's done is have a kid and fancy up her pubic area.