As the British government cut benefits for the poor at home, in Europe it fought to keep millions in subsidies for wealthy farmers

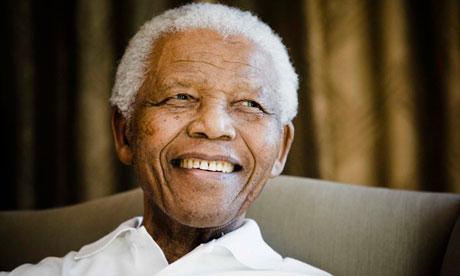

‘Most of the land in Britain is owned by very rich people, including millionaires from abroad who pay no UK taxes.' Illustration by Daniel Pudles

It's the silence that puzzles me. Last week the chancellor stood up in parliament to announce that benefits for the very poor would be cut yet again. On the same day, in Luxembourg, the British government battled to maintain benefits for the very rich. It won. As a result, some of the richest people in the country will each continue to receive millions of pounds in income support from taxpayers.

There has been not a whimper of protest. The Guardian hasn't mentioned it. UK Uncut is silent. So, at the other end of the spectrum, is the UK Independence party.

I'm talking about the most blatant transfer of money from the poor to the rich that has occurred in the era of universal suffrage. Farm subsidies. The main subsidy, the single farm payment, is doled out by the hectare. The more land you own or rent, the more money you receive.

Since 1999, more progressive European nations have been trying to limit the amount of public money a farmer can capture under the common agricultural policy. It looked as if, this year, they might at last succeed. But throughout the negotiations that ended last week, two governments in particular resisted: those resolute champions of the free market, Germany and the UK. Thanks to their lobbying, any decision has yet again been deferred.

There were two proposals for limiting handouts to the super-rich, known as capping and degressivity. Capping means that no one should receive more than a certain amount: the proposed limit was €300,000 (£250,000) a year. Degressivity means that beyond a certain point the rate received per hectare begins to fall. This was supposed to have kicked in at €150,000. The UK's environment secretary, Owen Paterson, knocked both proposals down.

When our government says "we must help the farmers", it means "we must help the 0.1%". Most of the land here is owned by exceedingly wealthy people. Some of them are millionaires from elsewhere: sheikhs, oligarchs and mining magnates who own vast estates in this country. Although they might pay no taxes in the UK, they receive millions in farm subsidies. They are the world's most successful benefit tourists. Yet, amid the manufactured terror of immigrants living off British welfare payments, we scarcely hear a word said against them.

The minister responsible for cutting income support for the poor, Iain Duncan Smith, lives on an estate owned by his wife's family. During the last 10 years it has received €1.5m in income support from taxpayers. How much more obvious do these double standards have to be before we begin to notice?

Thanks in large part to subsidies, the value of farmland in the UK has tripled in 10 years: it has risen faster than almost any other speculative asset. Farmers are exempted from inheritance tax and capital gains tax. They can build, without planning permission, structures which lesser mortals would be forbidden to erect, boosting both their capital and income. And they have a guaranteed income from the state. Yet all we hear from their leaders is one long whinge.

I have yet to detect a word of gratitude from the National Farmers' Union to the hard-pressed taxpayers who keep its members in such style. The NFU, dominated by the biggest landowners, has a peculiar genius for bringing out the violins. It pushes forward small, struggling hill farmers. The real beneficiaries of its policies are the arable barons hiding behind them.

An uncapped subsidy system damages the interests of small farmers. It reinforces the economies of scale enjoyed by the biggest landlords, helping them to drive the small producers out of business. A fair cap (say of €30,000) would help small farmers compete with the big ones.

So here's the question: why do we keep deferring to Big Farmer? Why do its sob stories go unchallenged? Why is this spectacular feudal boondoggle tolerated in the 21st century?

Here are three possible explanations. A high proportion of the books aimed at very young children are about farm animals. There is usually one family of every kind of animal, and they live in harmony with each other and the rosy-cheeked farmer. Understandably, slaughter, butchery, castration, separation, crates and cages, pesticides and slurry never feature. The petting farms that have sprung up around Britain reify and reinforce this fantasy. Perhaps these books unintentionally implant – at the very onset of consciousness – a deep, unquestioned faith in the virtues of the farm economy.

Perhaps too, after being brutally evicted from the land through centuries of enclosure, we have learned not to go there – even in our minds. To engage in this question feels like trespass, though we have handed over so much of our money that we could have bought all the land in Britain several times over.

Perhaps we also suffer from a cultural cringe towards people who make their living from the land and the sea, seeing their lives, however rich and cossetted they are, as somehow authentic, while ours feel artificial.

Whatever the reason, it's time we overcame these inhibitions and confronted this unembarrassed robbery of the poor by the rich. The current structure of farm subsidies epitomises the British government's defining project: capitalism for the poor and socialism for the rich.