An advocate of inequality, a friend to dictators and arms dealers, a champion of power and privilege and a scourge of the poor and vulnerable. A true blue class warrior.

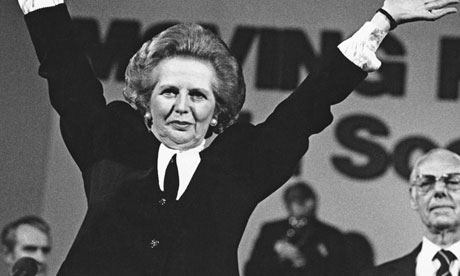

Thatcher is dead. But for years she was a shadow of her former self. After her fall from power in 1990 she slowly faded away from public life and when she did wander back onto the public stage the contrast between her frailty and the formidable figure of collective memory made these occasional spectacles almost surreal.

How we should respond when this elderly, diminished woman finally went to meet her maker has for some time been a minor talking point on the left. It is often said that we should not celebrate her passing. Not just because to do so would be distasteful, but because it is Thatcherism the idea not Thatcher the person that is the real enemy. This is of course true. Thatcher was no intellectual and did not invent what became known as Thatcherism. But neither was Thatcherism just some objectionable set of ideas to which the woman who lent it her name regrettably subscribed. Neoliberalism was, and is, a political project requiring political agency to achieve its hegemony; and in Britain it was Margaret Thatcher more than anyone who was responsible for transforming the neoliberal dreams of men like Hayek and Friedman into a waking political nightmare.

Margaret Hilda Thatcher was born in the Midlands town of Grantham in Lincolnshire on 13 October 1925, the second daughter of Alfred and Beatrice Roberts. Her father, whom she greatly admired, even idealised, was a local politician and lay preacher who owned and ran a grocery store in the town. The young Margaret Roberts was not close to her mother and once when asked about her only remarked, ‘Mother was marvellous – she helped Father.’

Her upbringing, though relatively privileged, was hardly the classic stuff of the British ruling class, and this fact doubtless strengthened her populist instincts and credentials. Both admirers and critics have attributed Thatcher’s politics to her small town, petty bourgeois roots. In 1983 the journalist Peter Riddell wrote that:

This rather romantic view of Thatcher’s politics was no doubt one that she herself shared. InThe Path To Power, she wrote: ‘There is no better course for understanding free-market economics than life in a corner shop.’ That the ‘free market’ policies associated with Thatcher in fact led to the domination of small town life by supermarkets and other powerful corporations, is just one of the many ways that the rhetoric and reality of her politics were cruelly out of sync.

In the Grantham of the real world, as opposed to the conservative utopia of Thatcher’s imagination, she will not be fondly remembered. During her premiership several of the town’s manufacturing companies were forced to shut down and the nearby Nottinghamshire coal mines were closed. As Tim Adams has reported, several years ago 85% of the readers of the town’s local paper voted against the erection of a bronze statue of Thatcher in favour of bringing back a fondly remembered disused steamroller, once a feature of the town’s largest public park.

Thatcher left Grantham in 1943 having won a scholarship at Somerville College, Oxford and seldom returned. She studied Chemistry and was appointed President of the University’s Conservative Association. After graduating in 1947 she worked for several years as a Research Chemist, first at British Xylonite (BX) Plastics, where she joined a trade union, the Association for Scientific Workers. She then joined the food company J. Lyons and Co., where it is often said that she was involved in the development of soft scoop ice cream. According to Jon Agar though, there is no firm evidence of this. [2]

In the General Elections of 1950 and 1951, when she was still in her mid-20s, Margaret Roberts, as she was then, stood as the Conservative candidate in the Labour stronghold of Dartford. 1951 was also the year she met, and soon afterwards married, the millionaire businessman Denis Thatcher. Her husband’s financial patronage proved invaluable, allowing her to train as a barrister and eventually to secure a seat in the constituency of Finchley in North London. Yet as Peter Clarke noted in reviewing her Path To Power, the importance of her husband’s considerable wealth was barely acknowledged by Thatcher. She preferred to dwell on her humble roots as a grocer’s daughter and to imagine that her achievements were attributable to drudgery and self-discipline.

Thatcher was first elected to the House of Commons in October 1959. She subsequently held junior posts in the Macmillan Government before becoming shadow spokesperson for education and in 1970 she entered the Cabinet as Education Secretary in Edward Heath’s ill-fated Tory Government. It was in this period that in response to demands for departmental spending cuts she cancelled free school milk, only to be forever taunted with the rhyme ‘Thatcher, Thatcher Milk Snatcher’.

Heath and Thatcher and were not personally well disposed to each other and along with other members of the Tory hard right she would later come to bitterly resent his supposedly conciliatory politics. As far as the Tory radicals were concerned, Heath had started out on the right track. At a January 1970 meeting at the Selsdon Park Hotel in Surrey, his shadow cabinet and policy team developed a set of reactionary policies designed to curtail the waves of radicalism and popular mobilisations which unnerved the British establishment in the 1960s. They proposed a new law on trespass (designed to combat the direct action protests of the student anti-racist movements) as well as new industrial regulations intended to curtail an increasingly intransigent working class. Meanwhile business and finance was to be deregulated and taxes cut. In words that could have been describing Thatcherism, the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson condemned the Selsdon policies as ‘an atavistic desire to reverse the course of 25 years of social revolution’ and ‘a wanton, calculated and deliberate return to greater inequality.’

If the policies were indeed intended to break with the post-war consensus (and it is not at all clear that they were), then Heath failed where Thatcher later succeeded. Attempts to limit the power of the trade unions ended in humiliating defeat at the hands of the National Union of Mineworkers and Heath’s free market policies were abandoned after Britain’s capitalists in fact showed little interest in investing in British industry. Other economic policies proved equally lamentable. The lifting of administrative controls over bank credit in 1971 (which had been lobbied for by the City of London) engineered a short-lived economic boom concentrated largely in property, which collapsed dramatically with the worldwide economic slump and the subsequent hike in oil prices.[3] In 1974 Heath was essentially forced from office by a newly assertive labour movement after he challenged the unions with the campaigning slogan ‘Who Governs Britain?’ – and lost.

Heath stayed on as Conservative Leader after suffering yet another general election defeat to his long term rival Harold Wilson. Meanwhile, Margaret Thatcher and other reactionaries in the Conservative Party, who longed for a spirited counter attack on the labour movement, began to coalesce around the figure of Keith Joseph – Heath’s former Secretary of State for Social Services who shortly after the first 1974 election defeat was apparently converted to the newly ascendant dogma of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism had been developed for several decades by a group of intellectuals belonging to an elite organisation called the Mount Pelerin Society. Probably the most influential of their number was the Austrian political economist Friedrich Hayek, who famously argued in TheRoad to Serfdom that any government intervention in the economy would ultimately lead to authoritarianism. Thatcher first read The Road to Serfdom at university and after his Damascus moment Keith Joseph encouraged her to explore Hayek’s other writings. (After being elected leader Thatcher is said to have brandished a copy of Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty, pronouncing, ‘This is what we believe!’)

In the UK Hayek’s ideas had been championed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think-tank funded by a millionaire businessman and run by two committed pamphleteers, Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon. Keith Joseph had been in contact with them both, as well as with other key neoliberal thinkers such as Alan Walters, an economist and a member of the Mount Pelerin Society, and Bill and Shirley Letwin (the parents of the Conservative Minister Oliver Letwin). With the support of these right-wing trailblazers, Thatcher and Joseph together founded a new think-tank called the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS), which set out to win over the Conservative Party to neoliberalism. Along with the Institute of Economic Affairs, the CPS became a hub for the New Right, which was now able to operate independently from the official Conservative Party policy machine, which was still aligned to the so called ‘One Nation Conservatism’ associated with Edward Heath and other influential Tories like Chris Patten and James Prior.

Thatcher came to lead the hard right faction of the Conservative Party as a result of a remarkably ill-judged speech given by Keith Joseph in October 1974 on the subject of the family and ‘civilised values’. Joseph spoke of a ‘degeneration’ and ‘moral decline reflected and intensified by economic decline’. The poor, he said, should be helped of course, but – and we hear echoes of this today in the speeches of Iain Duncan Smith – ‘to create more dependence is to destroy them morally’. Keith Joseph’s ultimate undoing was a section of the speech in which he said that the ‘balance of our population, our human stock is threatened’ since ‘a high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers… who were first pregnant in adolescence in social classes 4 and 5.’

Though often portrayed as what political journalists like to call a ‘gaffe’, Joseph had in fact long harboured such class prejudice and been inclined towards eugenics. A former Home Office official later recalled that whilst he was in government, civil servants had ‘been aware that he had inclinations in that direction but had steered him off.’[4]

Joseph was widely condemned for the speech and was discredited as a challenger for the Tory leadership. Thatcher, his closest political ally, stepped forward in his place with his full backing. She later recalled telling Joseph: ‘Look, Keith, if you’re not going to stand, I will because someone who represents our viewpoint has to stand.’[5]

Heath had lost two General Elections in one year, so Thatcher’s initial success was no great surprise. What was more unexpected was that the momentum of her success in the first ballot led her to an outright victory in the second after Heath dropped out. Thus, through some considerable good fortune, Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party in February 1975.

Her media advisor in her leadership campaign was Gordon Reece, a former television producer who had set up a company producing corporate videos and providing media advice to business executives. Thatcher, the supposed ‘conviction politician’, was thoroughly rebranded by Reece, who persuaded her to change her dress sense, posture and even to take elocution lessons. As Germaine Greer has noted, ‘Reece began the long process by which the millionaire's decorative wife with the fake, cut-glass accent was made over into the no-nonsense grocer’s daughter’. Thatcher herself later recalled: ‘Gordon was terrific. He said my hair and my clothes had to be changed and we would have to do something about my voice. It was quite an education because I had not thought about these things before.’[6]

Reece hired the advertising company Saatchi & Saatchi, whose chairman Tim Bell became another key advisor. Together Reece and Bell carefully orchestrated Thatcher’s media appearances and, in a break with the classic Tory strategy, courted the tabloid press, meeting regularly with Larry Lamb of The Sun and David English of the Daily Mail.[7]

The Sun, which had been owned by Rupert Murdoch since 1969, had for a period maintained a broadly left-wing stance, but by that point had switched its support to the Conservatives and despite having previously been highly critical of Thatcher during her time as Education Minister, had lent her its full support. As James Curran and Colin Leys note, this rightward shift reflected changes to the political economy of the media, which from the 1960s onwards became dominated by large corporations, reversing the trend toward journalist autonomy.[8]

Even with innovative campaigning strategies and the support of the majority of the press however, the Tories still lagged behind the Labour Party in the polls as it approached the end of its troubled five year term and Thatcher personally was considerably less popular than the Prime Minister James Callaghan. It was the wave of strikes during the winter of 1978/9 – the so called ‘Winter of Discontent’ – which would hand Thatcher her election victory. Her allies in the reactionary press seized the moment, attacking Callaghan as a complacent leader whose government was ‘held to ransom’ by militant trade unions. By February 1979 the Conservatives enjoyed an 18% lead and they went on to win a strong majority of 43 seats in the May 1979 election.

What was the nature of Thatcher’s electoral constituency? Though there was a notable rightward shift in the electorate in 1979, this trend has been hugely exaggerated by Thatcher’s supporters (who like to imagine her reactionary revolution as a popular uprising against the strictures of the social democratic state, rather than a top-down reassertion of class power). Like all political leaders she certainly enjoyed some cross-class support, but in the long run, working class support for the Conservatives continued its long term decline during her leadership.

The core Thatcherite voters, who were mobilised by the economic crisis and the rise of the ‘New Left’, were the most reactionary sections of the middle classes – the UKIP voters of today – whose antipathy towards trade unions and the left, and anxiety over a perceived moral and economic decline, meant they were receptive to Thatcher’s nationalist, authoritarian and petit bourgeois political rhetoric. Perhaps most importantly, though Thatcher was able to mobilise a significant section of the electorate, her support in no way represented a political mandate for neoliberalism. Indeed Thatcher and her advisors were always careful not to present their political agenda during election campaigns. During the 1979 campaign they chose to portray Thatcher as a rather homely figure and focused on attacking Labour over its lack of ‘economic credibility’. This strategy was to prove as ironic as Thatcher’s infamous promise as she entered 10 Downing Street that she would bring harmony and hope in the place of discord and despair.

The Thatcherite myth, which gradually became political common sense in Britain, is that the Conservatives introduced economic reforms which though painful and unpopular in the short term restored Britain to prosperity after years of Labour mismanagement of the economy. In fact Labour had been fairly successful in stabilising the economy. It brought down the high levels of inflation it had inherited from the Heath Government through a combination of spending cuts and wage restraints – attempting effectively to resolve the economic crisis by driving down the living standards of its own supporters. This policy had relied on the Labour Party’s relationship with the trade unions, which was obviously not an option for Thatcher. Instead her government turned to the newly fashionable theory of monetarism, according to which the ‘money supply’ was the key to controlling economic growth and inflation. The Labour leadership had already shifted somewhat towards ‘monetarist’ thinking in 1976, coerced by the IMF and influenced by James Callaghan’s son-in-law Peter Jay, but the Thatcherites now embraced a rather crude version – later referred to by Thatcher’s second Chancellor Nigel Lawson as ‘unreconstructed parochial monetarism’ – with characteristic zeal.

Thatcher, to be fair, was never able to put into practice the pure monetarism championed by her most dogmatic advisors who (beholden to neoclassical economics and thus misunderstanding the nature of money and credit) favoured controlling the monetary base as a counter-inflationary measure. Such an approach was effectively blocked by the political representatives of the City of London, who favoured instead an increase in interest rates.[9]And under Thatcher, what the City wanted, the City got. This included, most significantly, an end to exchange controls, which were abolished almost immediately, fatally undermining the political capacity for democratic management of the economy.

While the City boomed, British manufacturing suffered severely and unemployment doubled. Neither would recover. Meanwhile growth declined, inflation rose once again and, in the midst of a severe recession, Geoffrey Howe introduced public spending cuts. From a national perspective these policies were as disastrous as they were unpopular. Thatcher, having described Labour as ‘the natural party of unemployment’, and campaigned using the famous Saatchi & Saatchi poster showing a seemingly endless dole queue, now pushed unemployment up to three million. The ‘One Nation’ Tory Ian Gilmour, a member of Thatcher’s first Cabinet, noted that Thatcher and her neoliberal comrades were ‘largely cushioned by a surprising insensitivity to the human cost of their policy and by strong, if diminishing, feelings of dogmatic certainty’.[10] Nevertheless Thatcher (at this stage at least) knew when to back down. Having famously declared in October 1980 that, ‘The lady’s not for turning’, she quietly did just that in 1981.

Controlling the money supply proved far more difficult in practice than ideologues like Milton Friedman had imagined and the early commitments of the Thatcher Government were quietly abandoned. To consider this as a failure for Thatcherism though is to misunderstand the woman and the movement she headed. The Thatcherite interest in monetarism was not academic, but political. Peter Jay once remarked that explaining monetarism to Thatcher was ‘like showing Genghis Khan a map of the world’. Similarly Alan Budd, a founding member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, suggested that ‘the 1980s policies of attacking inflation by squeezing the economy and public spending were a cover to bash the workers.’[11]

What monetarism provided was an intellectual and technocratic rationale for cutting public spending and undermining the labour movement, not to mention providing more favourable conditions for financial capital, which in reality was the power behind Thatcher’s throne. Once the Thatcherites’ early approach to the economy threatened to undermine these strategic goals it was abandoned, or at least revised.

Thatcher’s early macro-economic policies were a significant departure from previous practices, but in many other respects her first few years in office were relatively cautious. This was partly because her Cabinet still included a number of influential, traditionally minded Conservatives (men she dubbed ‘wets’ for their failure to agree with her), but it was also because, despite her belligerent rhetoric, Thatcher was an adept strategist who understood that if she provoked a head on struggle with a united labour movement she would most likely lose. As one of her closest advisors, Charles Powell, remarked: ‘Mrs Thatcher was a radical, but she was a pragmatic radical.’ [12] So it was that when the National Coal Board announced pit closures in February 1981, the plans were quickly abandoned once the National Union of Mineworkers threatened to strike. As Nigel Lawson later commented: ‘Thatcher had very, very quickly backpedalled and she was quite right at that time because no preparation of any kind had been put in place for weathering a strike.’ [13] Indeed Lawson claims that on being appointed Energy Secretary in 1981, Thatcher told him, ‘Nigel, we mustn't have a coal strike.’

Though Thatcher initially shied away from conflict with the miners, secretly she prepared for war. When it came three years later, she was not only well prepared, but was emboldened by her victories in the Falklands conflict and the 1983 General Election. Her success in the latter, despite her risible record in office, is often attributed to the former and no doubt the Falklands conflict did have a significant impact on her confidence and status as a leader. But the truth is that in 1983 she was handed Britain on a plate by a divided opposition. In March 1981, a number of leading figures in the Labour Party broke off to form the Social Democratic Party, which then formed an electoral pact with the Liberals. In the 1983 election the SDP-Liberal Alliance secured 25% of the vote, but due to the first-past-the-post system received little in the way of seats. Meanwhile, the Conservatives’ share of the vote declined slightly, yet they secured the largest majority in the House of Commons since Atlee’s landslide of 1945. Just as the post-war Labour Government had fundamentally changed the governing consensus in Britain, so Thatcher would now do the same.

As Thatcher’s former advisor John Redwood later admitted, the Conservatives had once again been very vague about what policies they would introduce once they came to office.[14] But this did not matter. For Mrs Thatcher sought no mandate on policy, only a mandate to lead. Her Churchillian posturing during the Falklands conflict had given her a taste for war which was to define her. As John Campbell, one of her many biographers, notes:

At the top of Thatcher’s hit-list was the National Union of Mineworkers. Dubbed ‘the enemy within’, the miners’ crushing defeat after months of bitter struggle was probably Thatcher’s greatest single political achievement. It was not a popularity contest, and won her no new friends, but the battle fundamentally changed the political landscape of Britain. As Seumas Milne has suggested, the NUM represented an alternative vision for British society, one based on community, solidarity and collective action, rather than individualism and greed.[16] Their defeat therefore was not only a significant strategic victory, but it had an historic symbolic resonance. Thatcher’s equally truculent henchman, Norman Tebbit, later wrote that Thatcher had broken ‘not just a strike, but a spell’.

Having harnessed the full coercive powers of the state to defeat Britain’s most potent and politicised trade union, Thatcher moved to consolidate her victory. She passed legislative restrictions on picketing, strike actions and the closed shop. The trade union ‘reforms’ she instituted strengthened the hand of business and severely undermined the power and confidence of the labour movement. The left’s organisational base was further eroded by other policy innovations, now grimly familiar, such as restrictions on local government and the proliferation of quangos, the contracting out of local services and the privatisation of public utilities. In late 1984 Thatcher sold off British Telecom and she went on to sell off huge swathes of the Britain’s public infrastructure, including British Gas in December 1986, British Airways in February 1987, Rolls-Royce in May 1987, BAA in July 1987, British Steel in December 1988 and the regional water companies in December 1989.

These privatisations proved to be hugely profitable for the City of London and represented a massive transfer of wealth from public to private hands. They were carried out with a contempt for public opinion that came increasingly to characterise Thatcher’s reign. She famously described herself as a ‘conviction politician’, which in practice meant that in cabinet she was utterly intolerant of disagreement, and in government was contemptuous of all dissent. This autocratic style was not just a personal idiosyncrasy; it also reflected her underlying political philosophy – or perhaps the former attracted her to the latter. Precisely because of their peculiar notion of freedom, neoliberals have always harboured a deep suspicion of democracy. Looking back on Thatcher’s political legacy, Nigel Lawson remarked that as far as he was concerned democracy is ‘clearly less important than freedom’ and that to preserve the latter ‘strong government’ was necessary. This is precisely what Thatcher provided: a sustained, violent assault on British society launched on behalf of big business in the name of ‘strong government’ and cloaked in the rhetoric of national renewal. Her pugnacious political style would eventually prove her undoing, but there was method in her madness. Her aggression meant she was able to secure some decisive victories which could be consolidated and entrenched. She understood that the British political system afforded enough time to pursue an unpopular vanguardist strategy and betted (correctly) that social democrats would adapt to rather than challenge the profound changes she forced through.

Much has been made of the ideological power of Thatcher’s political vision, but in reality she did not seek to persuade people that ‘there is no alternative’. Rather she forced people to accept as much by attacking the social bases of collective action and ideas, emasculating those institutional forms that could make building any alternative possible or even imaginable. Like the Marxists she despised, Thatcher believed that ultimately it is the material conditions of life that determine political consciousness, and she sought therefore to bring about institutional changes which would carry with them an ideological reorientation. Hence why in an interview for the Sunday Times in May 1981 she made the chilling remark that, ‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.’ As Kean Birch has noted, the policy innovations in the Thatcher years represented a profound shift towards a political economy based on rising asset values rather than income. This, it was hoped, would tie people materially and ideologically to the capitalist system and create what Thatcherites, echoing Harold Macmillan, liked to call a ‘property-owning democracy’.

If Thatcher’s true goal was to change the heart and soul of the British public then she failed. It is clear from public opinion data that neoliberal policies remained remarkably unpopular under Thatcher and that the public remained stubbornly committed to the old social democratic consensus. In 1990, the sociologist Stephen Hill noted that the ‘evidence of the 1980s is that subordinate groups still subscribe widely to a radical-egalitarian and oppositional ideology.’[17]Indeed, Ivor Crewe long ago demolished the notion that Thatcher instituted any significant shift in public attitudes,[18] whilst the former Conservative Minister Ian Gilmour concedes that, ‘During the Thatcher years, public opinion remained centrist or, if anything, moved to the left.’

Be that as it may, the failure to win over people’s ‘hearts and souls’ did not derail Thatcher’s political project. Hegemony need not be built on popular consent and whatever Thatcher’s ambitions, it was never necessary to win us over to neoliberal ideas – only to neutralise any effective resistance. As Colin Leys has noted, ‘for an ideology to be hegemonic, it is not necessary that it be loved. It is merely necessary that it have no serious rival.’[19]

Thatcher succeeded in defeating all her serious rivals, but she was never loved, and she knew as much. In March 1990, drained of the confidence to fight another election and facing a national revolt against the poll tax, she told her confidant Woodrow Wyatt, ‘It’s me they don't like. It always has been.’[20] By that time she had a reputation as being impossibly obdurate and was increasingly seen as a political liability by her allies. Edwina Currie later commented: ‘If we wanted the revolution to be consolidated, she had become its main obstacle.’[21]

There is something pitiful about Thatcher's eventual decline and fall; that fearsome and formidable woman finally brought down by her pathetic, cowed comrades. And though she was never moved by the suffering of her many victims, she was nevertheless brought to tears as she contemplated her own misfortune. Her diehard supporters were also heartbroken. Andrew Marr remembers seeing a member of the Tory ‘No Turning Back’ group (which included Liam Fox, Francis Maude, Michael Portillo and Iain Duncan Smith) break down in tears at the news of her resignation. Beneath the pathos however lay a hidden truth about Thatcher and Thatcherism. For behind the revolt against her leadership was a contradiction that had always threatened to undermine the potent political alliance she led. John Campbell writes that: ‘Although in theory she rejected the concept of class… she was in truth an unabashed warrior on behalf of her own class.’ Campbell identifies hers as the ‘lower and middling middle class’, referred to by Thatcher as ‘the sort of people I grew up with.’ [22] In reality though it was not small business owners but multinational corporations, and the financial sector in particular, which benefited most from her reactionary revolution – and it was their interests that she most consistently served.

Thatcher had been able to appeal to a range of reactionary impulses which had developed during the slow burning crisis of the 1970s and had successfully fused them into a vaguely coherent political ideology. It is well understood that (like Rupert Murdoch) she sought to create mass support for big business by championing markets as an empowering, democratising force. More than that though, she also sought to portray markets as a moral force. Following Keith Joseph, she argued that state intervention had not only hampered Britain’s economic effectiveness, it had corrupted its moral character. As a leader of the New Right, she fused neoliberalism with the moralistic, reactionary politics of ‘Middle England’; tying the cold interests of capital to the bigoted preoccupations of the Tory base, who like Thatcher resented the complacent liberalism of the post-war establishment, its softness, permissiveness and acquiescence to the demands of society’s lower orders.

Economic elites and the lower middle class base shared an interest in undermining the power of trade unions, rolling back the welfare state and cutting taxes. But on certain questions their interests diverged and the key issue was Europe. Whilst a majority in the world of big business favoured greater European integration, this was virulently opposed by smaller businesses and the xenophobic Tory base. Thatcher herself, it should be said, was no Powellite nationalist. She had voted in favour of entry to the European Economic Community in 1970 and as Leader of the Opposition supported the ‘Yes Campaign’ in the 1975 referendum. In 1986 she gave her full support to the Single European Act, which opened up European markets to British corporations.[23] However, she strongly opposed the notion of supranational European institutions, perhaps out of authentically nationalist sentiment, or perhaps because she feared that her political victories might be diluted by European states which still retained their social democratic character.

Thatcher’s outspoken opposition to Europe towards the end of her premiership set her against influential members of her Cabinet like Nigel Lawson and Geoffrey Howe – the more authentic representatives of the social forces which, having been unleashed by Thatcher, had come to dominate British society under her leadership. Lawson resigned from the Cabinet in 1989 and Geoffrey Howe followed a year later. The latter delivered an infamous speech to the House of Commons in which, with Lawson sitting alongside him, he condemned Thatcher’s position on Europe saying, ‘What kind of vision is that for our business people, who trade there each day, for our financiers, who seek to make London the money capital of Europe…?’ As Robin Ramsay has detailed, Thatcher personally had no great love for financiers, but she had learned during her early ‘monetarist experiment’ that the City of London was one ‘interest group’ that she could not take on.[24] Years later then, when its political representatives demanded that she make what Nigel Lawson later called ‘the ultimate sacrifice’,[25] she displayed none of the defiance that had defined her time in office.

It is sometimes implied that during her many years in power Thatcher became ‘out of touch’ or drunk with power. But her authorised biographer Charles Moore, who interviewed her shortly before her final downfall, says he found her mood then to one of ‘unhappy fatalism’. Having failed to secure a decisive victory in a leadership challenge from Michael Heseltine, Thatcher lost the backing of her Cabinet and grudgingly agreed to resign. The Conservative Party Chairman Kenneth Baker told the media: ‘Once again Margaret Thatcher has put her country’s and party’s interests before personal considerations.’

Baker’s histrionics notwithstanding, Thatcher showed no grace in defeat. She resented her forced retirement and often criticised the new Tory leadership, particularly over Europe, which she came to believe represented some sort of ‘socialist’ threat. She gathered around her a team of writers to work on her memoirs in which she bitterly attacked her former comrades – Geoffrey Howe most of all, whom she accused of ‘bile and treachery’. Like Tony Blair years later, she embarked on a vanity tour and spent a period travelling around the world delivering highly paid speeches and socialising with the rich and powerful. She also took up a lucrative role working as a lobbyist for the American tobacco giant Philip Morris Inc, which hosted her $1million 70th birthday party.

Gradually though, as her proximity to power decreased, so did her health and her mental capacity. As Charles Moore writes:

By this point Thatcher’s brand of hard right politics looked as parochial and antiquated as the woman herself. A poignant moment came in 1997 when British Airways unveiled new logos for their aircraft tail fins, replacing the national colours of the Union Jack. In full sight of the television cameras, Thatcher covered a model of the new design with her handkerchief saying: ‘We fly the British flag, not these awful things you are putting on tails.’

Maybe the designs were awful. They were later abandoned by BA. But the spectacle powerfully illustrated how out of step Thatcher had become with the imperatives of a corporate elite whose power and privilege she had worked so tirelessly to defend and to bolster. Capital is a fickle thing and big business had by then already defected en masse to New Labour which looked like a far more viable prospect for consolidating the victories of Thatcher’s cruel war than the fractious party she left in her wake. Her belligerent, divisive politics had long since served its usefulness and so had the woman herself. One of her last political acts was to take a public stand in defence of Augusto Pinochet, the decrepit Chilean dictator thought to have imprisoned and tortured over 40,000 political opponents during his seventeen years in power.

In 2002, having suffered a series of minor strokes, Thatcher was ordered by doctors to refrain from any public speaking and in the years that followed her health further deteriorated. Her loss of physical and mental capacity was made the focus of the curiously apolitical biopic The Iron Lady. The film was criticised by the Tory right, who preferred to remember Thatcher at her most potent and combative. In a sense they are right. That too, I think, is how we should remember her. Not for what she became once her faculties failed her, but for what she was at the height of her power: an advocate of inequality, a friend to dictators and arms dealers, a champion of power and privilege and a scourge of the poor and vulnerable. A true blue class warrior.

Tom Millsis a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Bath and a co-editor of New Left Project, where this article was first published

1. Cited in Bob Jessop et al, Thatcherism: A Tale of Two Nations (Polity Press, 1988) p.4.

2. Jon Agar, ‘Thatcher, Scientist’, Notes and Records of the Royal Society, Vol.65, No.3, 20 September 2011, 215-232. http://rsnr.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/65/3/215.full

3. ‘Back to the future: the 1970s reconsidered’, Lobster, Winter 1998, Issue 34.

4. Cited in John Welshman, From transmitted deprivation to social exclusion: policy, poverty and parenting (The Policy Press, 2007) p.62.

5. Cited in John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.72.

6. Thatcher: The Path to Power—and Beyond, BBC1, 12 June 1995.

7. Mark Hollingsworth, The Ultimate Spin Doctor: the Life and Fast Times of Tim Bell (1997) p.70

8. James Curran and Colin Leys, ‘Media and the Decline of Liberal Corporatism in Britain’, in James Curran and Myung-Jin Park (eds.), De-Westernizing Media Studies (London: Routledge, 2000) pp. 221-36.

9. Robin Ramsay, ‘Mrs Thatcher, North Sea oil and the hegemony of the City’, Lobster, Issue 27: 1994.

10. Ian Gilmour, Dancing with Dogma (Simon & Schuster, 1992) p.60.

11. Quoted in David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism p.59.

12. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.351.

16. Seumas Milne, The Enemy Within: The Secret War Against the Miners (London: Verso, 1994) p.ix.

17. Stephen Hill, ‘Britain: The Dominant Ideology Thesis after a decade’, In Nicholas Abercrombie, Stephen Hill and Bryan S. Turner (eds.), Dominant Ideologies (London: Unwin Hyman, 1990) p.6.

18. Ivor Crewe, ‘Values: The Crusade that Failed’, in Dennis Kavanagh and Anthony Seldon (eds.), The Thatcher Effect (Oxford University Press, 1989) pp. 239-50.

19. Colin Leys, ‘Still a question of hegemony’, New Left Review, 181, p.127.

20. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.674.

21. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

22. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.352.

23. Andrew Gamble, ‘Europe and America’, in Ben Jackson and Robert Saunders (eds.),Making Thatcher’s Britain (Oxford University Press, 2012) p.219.

24. Robin Ramsay, ‘Mrs Thatcher, North Sea oil and the hegemony of the City’, Lobster, Issue 27: 1994.

25. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

How we should respond when this elderly, diminished woman finally went to meet her maker has for some time been a minor talking point on the left. It is often said that we should not celebrate her passing. Not just because to do so would be distasteful, but because it is Thatcherism the idea not Thatcher the person that is the real enemy. This is of course true. Thatcher was no intellectual and did not invent what became known as Thatcherism. But neither was Thatcherism just some objectionable set of ideas to which the woman who lent it her name regrettably subscribed. Neoliberalism was, and is, a political project requiring political agency to achieve its hegemony; and in Britain it was Margaret Thatcher more than anyone who was responsible for transforming the neoliberal dreams of men like Hayek and Friedman into a waking political nightmare.

Margaret Hilda Thatcher was born in the Midlands town of Grantham in Lincolnshire on 13 October 1925, the second daughter of Alfred and Beatrice Roberts. Her father, whom she greatly admired, even idealised, was a local politician and lay preacher who owned and ran a grocery store in the town. The young Margaret Roberts was not close to her mother and once when asked about her only remarked, ‘Mother was marvellous – she helped Father.’

Her upbringing, though relatively privileged, was hardly the classic stuff of the British ruling class, and this fact doubtless strengthened her populist instincts and credentials. Both admirers and critics have attributed Thatcher’s politics to her small town, petty bourgeois roots. In 1983 the journalist Peter Riddell wrote that:

Thatcherism is essentially an instinct, a sense of moral values and an approach to leadership rather than ideology. It is an expression of Mrs Thatcher’s upbringing in Grantham, her background of hard work and family responsibility, ambition and postponed satisfaction, duty and patriotism.[1]

This rather romantic view of Thatcher’s politics was no doubt one that she herself shared. InThe Path To Power, she wrote: ‘There is no better course for understanding free-market economics than life in a corner shop.’ That the ‘free market’ policies associated with Thatcher in fact led to the domination of small town life by supermarkets and other powerful corporations, is just one of the many ways that the rhetoric and reality of her politics were cruelly out of sync.

In the Grantham of the real world, as opposed to the conservative utopia of Thatcher’s imagination, she will not be fondly remembered. During her premiership several of the town’s manufacturing companies were forced to shut down and the nearby Nottinghamshire coal mines were closed. As Tim Adams has reported, several years ago 85% of the readers of the town’s local paper voted against the erection of a bronze statue of Thatcher in favour of bringing back a fondly remembered disused steamroller, once a feature of the town’s largest public park.

Thatcher left Grantham in 1943 having won a scholarship at Somerville College, Oxford and seldom returned. She studied Chemistry and was appointed President of the University’s Conservative Association. After graduating in 1947 she worked for several years as a Research Chemist, first at British Xylonite (BX) Plastics, where she joined a trade union, the Association for Scientific Workers. She then joined the food company J. Lyons and Co., where it is often said that she was involved in the development of soft scoop ice cream. According to Jon Agar though, there is no firm evidence of this. [2]

In the General Elections of 1950 and 1951, when she was still in her mid-20s, Margaret Roberts, as she was then, stood as the Conservative candidate in the Labour stronghold of Dartford. 1951 was also the year she met, and soon afterwards married, the millionaire businessman Denis Thatcher. Her husband’s financial patronage proved invaluable, allowing her to train as a barrister and eventually to secure a seat in the constituency of Finchley in North London. Yet as Peter Clarke noted in reviewing her Path To Power, the importance of her husband’s considerable wealth was barely acknowledged by Thatcher. She preferred to dwell on her humble roots as a grocer’s daughter and to imagine that her achievements were attributable to drudgery and self-discipline.

Thatcher was first elected to the House of Commons in October 1959. She subsequently held junior posts in the Macmillan Government before becoming shadow spokesperson for education and in 1970 she entered the Cabinet as Education Secretary in Edward Heath’s ill-fated Tory Government. It was in this period that in response to demands for departmental spending cuts she cancelled free school milk, only to be forever taunted with the rhyme ‘Thatcher, Thatcher Milk Snatcher’.

Heath and Thatcher and were not personally well disposed to each other and along with other members of the Tory hard right she would later come to bitterly resent his supposedly conciliatory politics. As far as the Tory radicals were concerned, Heath had started out on the right track. At a January 1970 meeting at the Selsdon Park Hotel in Surrey, his shadow cabinet and policy team developed a set of reactionary policies designed to curtail the waves of radicalism and popular mobilisations which unnerved the British establishment in the 1960s. They proposed a new law on trespass (designed to combat the direct action protests of the student anti-racist movements) as well as new industrial regulations intended to curtail an increasingly intransigent working class. Meanwhile business and finance was to be deregulated and taxes cut. In words that could have been describing Thatcherism, the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson condemned the Selsdon policies as ‘an atavistic desire to reverse the course of 25 years of social revolution’ and ‘a wanton, calculated and deliberate return to greater inequality.’

If the policies were indeed intended to break with the post-war consensus (and it is not at all clear that they were), then Heath failed where Thatcher later succeeded. Attempts to limit the power of the trade unions ended in humiliating defeat at the hands of the National Union of Mineworkers and Heath’s free market policies were abandoned after Britain’s capitalists in fact showed little interest in investing in British industry. Other economic policies proved equally lamentable. The lifting of administrative controls over bank credit in 1971 (which had been lobbied for by the City of London) engineered a short-lived economic boom concentrated largely in property, which collapsed dramatically with the worldwide economic slump and the subsequent hike in oil prices.[3] In 1974 Heath was essentially forced from office by a newly assertive labour movement after he challenged the unions with the campaigning slogan ‘Who Governs Britain?’ – and lost.

Heath stayed on as Conservative Leader after suffering yet another general election defeat to his long term rival Harold Wilson. Meanwhile, Margaret Thatcher and other reactionaries in the Conservative Party, who longed for a spirited counter attack on the labour movement, began to coalesce around the figure of Keith Joseph – Heath’s former Secretary of State for Social Services who shortly after the first 1974 election defeat was apparently converted to the newly ascendant dogma of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism had been developed for several decades by a group of intellectuals belonging to an elite organisation called the Mount Pelerin Society. Probably the most influential of their number was the Austrian political economist Friedrich Hayek, who famously argued in TheRoad to Serfdom that any government intervention in the economy would ultimately lead to authoritarianism. Thatcher first read The Road to Serfdom at university and after his Damascus moment Keith Joseph encouraged her to explore Hayek’s other writings. (After being elected leader Thatcher is said to have brandished a copy of Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty, pronouncing, ‘This is what we believe!’)

In the UK Hayek’s ideas had been championed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think-tank funded by a millionaire businessman and run by two committed pamphleteers, Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon. Keith Joseph had been in contact with them both, as well as with other key neoliberal thinkers such as Alan Walters, an economist and a member of the Mount Pelerin Society, and Bill and Shirley Letwin (the parents of the Conservative Minister Oliver Letwin). With the support of these right-wing trailblazers, Thatcher and Joseph together founded a new think-tank called the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS), which set out to win over the Conservative Party to neoliberalism. Along with the Institute of Economic Affairs, the CPS became a hub for the New Right, which was now able to operate independently from the official Conservative Party policy machine, which was still aligned to the so called ‘One Nation Conservatism’ associated with Edward Heath and other influential Tories like Chris Patten and James Prior.

Thatcher came to lead the hard right faction of the Conservative Party as a result of a remarkably ill-judged speech given by Keith Joseph in October 1974 on the subject of the family and ‘civilised values’. Joseph spoke of a ‘degeneration’ and ‘moral decline reflected and intensified by economic decline’. The poor, he said, should be helped of course, but – and we hear echoes of this today in the speeches of Iain Duncan Smith – ‘to create more dependence is to destroy them morally’. Keith Joseph’s ultimate undoing was a section of the speech in which he said that the ‘balance of our population, our human stock is threatened’ since ‘a high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers… who were first pregnant in adolescence in social classes 4 and 5.’

Though often portrayed as what political journalists like to call a ‘gaffe’, Joseph had in fact long harboured such class prejudice and been inclined towards eugenics. A former Home Office official later recalled that whilst he was in government, civil servants had ‘been aware that he had inclinations in that direction but had steered him off.’[4]

Joseph was widely condemned for the speech and was discredited as a challenger for the Tory leadership. Thatcher, his closest political ally, stepped forward in his place with his full backing. She later recalled telling Joseph: ‘Look, Keith, if you’re not going to stand, I will because someone who represents our viewpoint has to stand.’[5]

Heath had lost two General Elections in one year, so Thatcher’s initial success was no great surprise. What was more unexpected was that the momentum of her success in the first ballot led her to an outright victory in the second after Heath dropped out. Thus, through some considerable good fortune, Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party in February 1975.

Her media advisor in her leadership campaign was Gordon Reece, a former television producer who had set up a company producing corporate videos and providing media advice to business executives. Thatcher, the supposed ‘conviction politician’, was thoroughly rebranded by Reece, who persuaded her to change her dress sense, posture and even to take elocution lessons. As Germaine Greer has noted, ‘Reece began the long process by which the millionaire's decorative wife with the fake, cut-glass accent was made over into the no-nonsense grocer’s daughter’. Thatcher herself later recalled: ‘Gordon was terrific. He said my hair and my clothes had to be changed and we would have to do something about my voice. It was quite an education because I had not thought about these things before.’[6]

Reece hired the advertising company Saatchi & Saatchi, whose chairman Tim Bell became another key advisor. Together Reece and Bell carefully orchestrated Thatcher’s media appearances and, in a break with the classic Tory strategy, courted the tabloid press, meeting regularly with Larry Lamb of The Sun and David English of the Daily Mail.[7]

The Sun, which had been owned by Rupert Murdoch since 1969, had for a period maintained a broadly left-wing stance, but by that point had switched its support to the Conservatives and despite having previously been highly critical of Thatcher during her time as Education Minister, had lent her its full support. As James Curran and Colin Leys note, this rightward shift reflected changes to the political economy of the media, which from the 1960s onwards became dominated by large corporations, reversing the trend toward journalist autonomy.[8]

Even with innovative campaigning strategies and the support of the majority of the press however, the Tories still lagged behind the Labour Party in the polls as it approached the end of its troubled five year term and Thatcher personally was considerably less popular than the Prime Minister James Callaghan. It was the wave of strikes during the winter of 1978/9 – the so called ‘Winter of Discontent’ – which would hand Thatcher her election victory. Her allies in the reactionary press seized the moment, attacking Callaghan as a complacent leader whose government was ‘held to ransom’ by militant trade unions. By February 1979 the Conservatives enjoyed an 18% lead and they went on to win a strong majority of 43 seats in the May 1979 election.

What was the nature of Thatcher’s electoral constituency? Though there was a notable rightward shift in the electorate in 1979, this trend has been hugely exaggerated by Thatcher’s supporters (who like to imagine her reactionary revolution as a popular uprising against the strictures of the social democratic state, rather than a top-down reassertion of class power). Like all political leaders she certainly enjoyed some cross-class support, but in the long run, working class support for the Conservatives continued its long term decline during her leadership.

The core Thatcherite voters, who were mobilised by the economic crisis and the rise of the ‘New Left’, were the most reactionary sections of the middle classes – the UKIP voters of today – whose antipathy towards trade unions and the left, and anxiety over a perceived moral and economic decline, meant they were receptive to Thatcher’s nationalist, authoritarian and petit bourgeois political rhetoric. Perhaps most importantly, though Thatcher was able to mobilise a significant section of the electorate, her support in no way represented a political mandate for neoliberalism. Indeed Thatcher and her advisors were always careful not to present their political agenda during election campaigns. During the 1979 campaign they chose to portray Thatcher as a rather homely figure and focused on attacking Labour over its lack of ‘economic credibility’. This strategy was to prove as ironic as Thatcher’s infamous promise as she entered 10 Downing Street that she would bring harmony and hope in the place of discord and despair.

The Thatcherite myth, which gradually became political common sense in Britain, is that the Conservatives introduced economic reforms which though painful and unpopular in the short term restored Britain to prosperity after years of Labour mismanagement of the economy. In fact Labour had been fairly successful in stabilising the economy. It brought down the high levels of inflation it had inherited from the Heath Government through a combination of spending cuts and wage restraints – attempting effectively to resolve the economic crisis by driving down the living standards of its own supporters. This policy had relied on the Labour Party’s relationship with the trade unions, which was obviously not an option for Thatcher. Instead her government turned to the newly fashionable theory of monetarism, according to which the ‘money supply’ was the key to controlling economic growth and inflation. The Labour leadership had already shifted somewhat towards ‘monetarist’ thinking in 1976, coerced by the IMF and influenced by James Callaghan’s son-in-law Peter Jay, but the Thatcherites now embraced a rather crude version – later referred to by Thatcher’s second Chancellor Nigel Lawson as ‘unreconstructed parochial monetarism’ – with characteristic zeal.

Thatcher, to be fair, was never able to put into practice the pure monetarism championed by her most dogmatic advisors who (beholden to neoclassical economics and thus misunderstanding the nature of money and credit) favoured controlling the monetary base as a counter-inflationary measure. Such an approach was effectively blocked by the political representatives of the City of London, who favoured instead an increase in interest rates.[9]And under Thatcher, what the City wanted, the City got. This included, most significantly, an end to exchange controls, which were abolished almost immediately, fatally undermining the political capacity for democratic management of the economy.

While the City boomed, British manufacturing suffered severely and unemployment doubled. Neither would recover. Meanwhile growth declined, inflation rose once again and, in the midst of a severe recession, Geoffrey Howe introduced public spending cuts. From a national perspective these policies were as disastrous as they were unpopular. Thatcher, having described Labour as ‘the natural party of unemployment’, and campaigned using the famous Saatchi & Saatchi poster showing a seemingly endless dole queue, now pushed unemployment up to three million. The ‘One Nation’ Tory Ian Gilmour, a member of Thatcher’s first Cabinet, noted that Thatcher and her neoliberal comrades were ‘largely cushioned by a surprising insensitivity to the human cost of their policy and by strong, if diminishing, feelings of dogmatic certainty’.[10] Nevertheless Thatcher (at this stage at least) knew when to back down. Having famously declared in October 1980 that, ‘The lady’s not for turning’, she quietly did just that in 1981.

Controlling the money supply proved far more difficult in practice than ideologues like Milton Friedman had imagined and the early commitments of the Thatcher Government were quietly abandoned. To consider this as a failure for Thatcherism though is to misunderstand the woman and the movement she headed. The Thatcherite interest in monetarism was not academic, but political. Peter Jay once remarked that explaining monetarism to Thatcher was ‘like showing Genghis Khan a map of the world’. Similarly Alan Budd, a founding member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, suggested that ‘the 1980s policies of attacking inflation by squeezing the economy and public spending were a cover to bash the workers.’[11]

What monetarism provided was an intellectual and technocratic rationale for cutting public spending and undermining the labour movement, not to mention providing more favourable conditions for financial capital, which in reality was the power behind Thatcher’s throne. Once the Thatcherites’ early approach to the economy threatened to undermine these strategic goals it was abandoned, or at least revised.

Thatcher’s early macro-economic policies were a significant departure from previous practices, but in many other respects her first few years in office were relatively cautious. This was partly because her Cabinet still included a number of influential, traditionally minded Conservatives (men she dubbed ‘wets’ for their failure to agree with her), but it was also because, despite her belligerent rhetoric, Thatcher was an adept strategist who understood that if she provoked a head on struggle with a united labour movement she would most likely lose. As one of her closest advisors, Charles Powell, remarked: ‘Mrs Thatcher was a radical, but she was a pragmatic radical.’ [12] So it was that when the National Coal Board announced pit closures in February 1981, the plans were quickly abandoned once the National Union of Mineworkers threatened to strike. As Nigel Lawson later commented: ‘Thatcher had very, very quickly backpedalled and she was quite right at that time because no preparation of any kind had been put in place for weathering a strike.’ [13] Indeed Lawson claims that on being appointed Energy Secretary in 1981, Thatcher told him, ‘Nigel, we mustn't have a coal strike.’

Though Thatcher initially shied away from conflict with the miners, secretly she prepared for war. When it came three years later, she was not only well prepared, but was emboldened by her victories in the Falklands conflict and the 1983 General Election. Her success in the latter, despite her risible record in office, is often attributed to the former and no doubt the Falklands conflict did have a significant impact on her confidence and status as a leader. But the truth is that in 1983 she was handed Britain on a plate by a divided opposition. In March 1981, a number of leading figures in the Labour Party broke off to form the Social Democratic Party, which then formed an electoral pact with the Liberals. In the 1983 election the SDP-Liberal Alliance secured 25% of the vote, but due to the first-past-the-post system received little in the way of seats. Meanwhile, the Conservatives’ share of the vote declined slightly, yet they secured the largest majority in the House of Commons since Atlee’s landslide of 1945. Just as the post-war Labour Government had fundamentally changed the governing consensus in Britain, so Thatcher would now do the same.

As Thatcher’s former advisor John Redwood later admitted, the Conservatives had once again been very vague about what policies they would introduce once they came to office.[14] But this did not matter. For Mrs Thatcher sought no mandate on policy, only a mandate to lead. Her Churchillian posturing during the Falklands conflict had given her a taste for war which was to define her. As John Campbell, one of her many biographers, notes:

One of Margaret Thatcher’s defining characteristics as a politician was a need for enemies. To fuel the aggression that drove her career she had to find new antagonists all the time to be successively demonised, confronted and defeated.[15]

At the top of Thatcher’s hit-list was the National Union of Mineworkers. Dubbed ‘the enemy within’, the miners’ crushing defeat after months of bitter struggle was probably Thatcher’s greatest single political achievement. It was not a popularity contest, and won her no new friends, but the battle fundamentally changed the political landscape of Britain. As Seumas Milne has suggested, the NUM represented an alternative vision for British society, one based on community, solidarity and collective action, rather than individualism and greed.[16] Their defeat therefore was not only a significant strategic victory, but it had an historic symbolic resonance. Thatcher’s equally truculent henchman, Norman Tebbit, later wrote that Thatcher had broken ‘not just a strike, but a spell’.

Having harnessed the full coercive powers of the state to defeat Britain’s most potent and politicised trade union, Thatcher moved to consolidate her victory. She passed legislative restrictions on picketing, strike actions and the closed shop. The trade union ‘reforms’ she instituted strengthened the hand of business and severely undermined the power and confidence of the labour movement. The left’s organisational base was further eroded by other policy innovations, now grimly familiar, such as restrictions on local government and the proliferation of quangos, the contracting out of local services and the privatisation of public utilities. In late 1984 Thatcher sold off British Telecom and she went on to sell off huge swathes of the Britain’s public infrastructure, including British Gas in December 1986, British Airways in February 1987, Rolls-Royce in May 1987, BAA in July 1987, British Steel in December 1988 and the regional water companies in December 1989.

These privatisations proved to be hugely profitable for the City of London and represented a massive transfer of wealth from public to private hands. They were carried out with a contempt for public opinion that came increasingly to characterise Thatcher’s reign. She famously described herself as a ‘conviction politician’, which in practice meant that in cabinet she was utterly intolerant of disagreement, and in government was contemptuous of all dissent. This autocratic style was not just a personal idiosyncrasy; it also reflected her underlying political philosophy – or perhaps the former attracted her to the latter. Precisely because of their peculiar notion of freedom, neoliberals have always harboured a deep suspicion of democracy. Looking back on Thatcher’s political legacy, Nigel Lawson remarked that as far as he was concerned democracy is ‘clearly less important than freedom’ and that to preserve the latter ‘strong government’ was necessary. This is precisely what Thatcher provided: a sustained, violent assault on British society launched on behalf of big business in the name of ‘strong government’ and cloaked in the rhetoric of national renewal. Her pugnacious political style would eventually prove her undoing, but there was method in her madness. Her aggression meant she was able to secure some decisive victories which could be consolidated and entrenched. She understood that the British political system afforded enough time to pursue an unpopular vanguardist strategy and betted (correctly) that social democrats would adapt to rather than challenge the profound changes she forced through.

Much has been made of the ideological power of Thatcher’s political vision, but in reality she did not seek to persuade people that ‘there is no alternative’. Rather she forced people to accept as much by attacking the social bases of collective action and ideas, emasculating those institutional forms that could make building any alternative possible or even imaginable. Like the Marxists she despised, Thatcher believed that ultimately it is the material conditions of life that determine political consciousness, and she sought therefore to bring about institutional changes which would carry with them an ideological reorientation. Hence why in an interview for the Sunday Times in May 1981 she made the chilling remark that, ‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.’ As Kean Birch has noted, the policy innovations in the Thatcher years represented a profound shift towards a political economy based on rising asset values rather than income. This, it was hoped, would tie people materially and ideologically to the capitalist system and create what Thatcherites, echoing Harold Macmillan, liked to call a ‘property-owning democracy’.

If Thatcher’s true goal was to change the heart and soul of the British public then she failed. It is clear from public opinion data that neoliberal policies remained remarkably unpopular under Thatcher and that the public remained stubbornly committed to the old social democratic consensus. In 1990, the sociologist Stephen Hill noted that the ‘evidence of the 1980s is that subordinate groups still subscribe widely to a radical-egalitarian and oppositional ideology.’[17]Indeed, Ivor Crewe long ago demolished the notion that Thatcher instituted any significant shift in public attitudes,[18] whilst the former Conservative Minister Ian Gilmour concedes that, ‘During the Thatcher years, public opinion remained centrist or, if anything, moved to the left.’

Be that as it may, the failure to win over people’s ‘hearts and souls’ did not derail Thatcher’s political project. Hegemony need not be built on popular consent and whatever Thatcher’s ambitions, it was never necessary to win us over to neoliberal ideas – only to neutralise any effective resistance. As Colin Leys has noted, ‘for an ideology to be hegemonic, it is not necessary that it be loved. It is merely necessary that it have no serious rival.’[19]

Thatcher succeeded in defeating all her serious rivals, but she was never loved, and she knew as much. In March 1990, drained of the confidence to fight another election and facing a national revolt against the poll tax, she told her confidant Woodrow Wyatt, ‘It’s me they don't like. It always has been.’[20] By that time she had a reputation as being impossibly obdurate and was increasingly seen as a political liability by her allies. Edwina Currie later commented: ‘If we wanted the revolution to be consolidated, she had become its main obstacle.’[21]

There is something pitiful about Thatcher's eventual decline and fall; that fearsome and formidable woman finally brought down by her pathetic, cowed comrades. And though she was never moved by the suffering of her many victims, she was nevertheless brought to tears as she contemplated her own misfortune. Her diehard supporters were also heartbroken. Andrew Marr remembers seeing a member of the Tory ‘No Turning Back’ group (which included Liam Fox, Francis Maude, Michael Portillo and Iain Duncan Smith) break down in tears at the news of her resignation. Beneath the pathos however lay a hidden truth about Thatcher and Thatcherism. For behind the revolt against her leadership was a contradiction that had always threatened to undermine the potent political alliance she led. John Campbell writes that: ‘Although in theory she rejected the concept of class… she was in truth an unabashed warrior on behalf of her own class.’ Campbell identifies hers as the ‘lower and middling middle class’, referred to by Thatcher as ‘the sort of people I grew up with.’ [22] In reality though it was not small business owners but multinational corporations, and the financial sector in particular, which benefited most from her reactionary revolution – and it was their interests that she most consistently served.

Thatcher had been able to appeal to a range of reactionary impulses which had developed during the slow burning crisis of the 1970s and had successfully fused them into a vaguely coherent political ideology. It is well understood that (like Rupert Murdoch) she sought to create mass support for big business by championing markets as an empowering, democratising force. More than that though, she also sought to portray markets as a moral force. Following Keith Joseph, she argued that state intervention had not only hampered Britain’s economic effectiveness, it had corrupted its moral character. As a leader of the New Right, she fused neoliberalism with the moralistic, reactionary politics of ‘Middle England’; tying the cold interests of capital to the bigoted preoccupations of the Tory base, who like Thatcher resented the complacent liberalism of the post-war establishment, its softness, permissiveness and acquiescence to the demands of society’s lower orders.

Economic elites and the lower middle class base shared an interest in undermining the power of trade unions, rolling back the welfare state and cutting taxes. But on certain questions their interests diverged and the key issue was Europe. Whilst a majority in the world of big business favoured greater European integration, this was virulently opposed by smaller businesses and the xenophobic Tory base. Thatcher herself, it should be said, was no Powellite nationalist. She had voted in favour of entry to the European Economic Community in 1970 and as Leader of the Opposition supported the ‘Yes Campaign’ in the 1975 referendum. In 1986 she gave her full support to the Single European Act, which opened up European markets to British corporations.[23] However, she strongly opposed the notion of supranational European institutions, perhaps out of authentically nationalist sentiment, or perhaps because she feared that her political victories might be diluted by European states which still retained their social democratic character.

Thatcher’s outspoken opposition to Europe towards the end of her premiership set her against influential members of her Cabinet like Nigel Lawson and Geoffrey Howe – the more authentic representatives of the social forces which, having been unleashed by Thatcher, had come to dominate British society under her leadership. Lawson resigned from the Cabinet in 1989 and Geoffrey Howe followed a year later. The latter delivered an infamous speech to the House of Commons in which, with Lawson sitting alongside him, he condemned Thatcher’s position on Europe saying, ‘What kind of vision is that for our business people, who trade there each day, for our financiers, who seek to make London the money capital of Europe…?’ As Robin Ramsay has detailed, Thatcher personally had no great love for financiers, but she had learned during her early ‘monetarist experiment’ that the City of London was one ‘interest group’ that she could not take on.[24] Years later then, when its political representatives demanded that she make what Nigel Lawson later called ‘the ultimate sacrifice’,[25] she displayed none of the defiance that had defined her time in office.

It is sometimes implied that during her many years in power Thatcher became ‘out of touch’ or drunk with power. But her authorised biographer Charles Moore, who interviewed her shortly before her final downfall, says he found her mood then to one of ‘unhappy fatalism’. Having failed to secure a decisive victory in a leadership challenge from Michael Heseltine, Thatcher lost the backing of her Cabinet and grudgingly agreed to resign. The Conservative Party Chairman Kenneth Baker told the media: ‘Once again Margaret Thatcher has put her country’s and party’s interests before personal considerations.’

Baker’s histrionics notwithstanding, Thatcher showed no grace in defeat. She resented her forced retirement and often criticised the new Tory leadership, particularly over Europe, which she came to believe represented some sort of ‘socialist’ threat. She gathered around her a team of writers to work on her memoirs in which she bitterly attacked her former comrades – Geoffrey Howe most of all, whom she accused of ‘bile and treachery’. Like Tony Blair years later, she embarked on a vanity tour and spent a period travelling around the world delivering highly paid speeches and socialising with the rich and powerful. She also took up a lucrative role working as a lobbyist for the American tobacco giant Philip Morris Inc, which hosted her $1million 70th birthday party.

Gradually though, as her proximity to power decreased, so did her health and her mental capacity. As Charles Moore writes:

The passage of time, and possibly the delayed effect of so many years of relentless work, blunted the edge of Lady Thatcher’s mind. By the late 1990s it became gradually apparent that her short-term memory was failing. ... By the time the century turned, she had lost her – until then – passionate and detailed interest in current events.

By this point Thatcher’s brand of hard right politics looked as parochial and antiquated as the woman herself. A poignant moment came in 1997 when British Airways unveiled new logos for their aircraft tail fins, replacing the national colours of the Union Jack. In full sight of the television cameras, Thatcher covered a model of the new design with her handkerchief saying: ‘We fly the British flag, not these awful things you are putting on tails.’

Maybe the designs were awful. They were later abandoned by BA. But the spectacle powerfully illustrated how out of step Thatcher had become with the imperatives of a corporate elite whose power and privilege she had worked so tirelessly to defend and to bolster. Capital is a fickle thing and big business had by then already defected en masse to New Labour which looked like a far more viable prospect for consolidating the victories of Thatcher’s cruel war than the fractious party she left in her wake. Her belligerent, divisive politics had long since served its usefulness and so had the woman herself. One of her last political acts was to take a public stand in defence of Augusto Pinochet, the decrepit Chilean dictator thought to have imprisoned and tortured over 40,000 political opponents during his seventeen years in power.

In 2002, having suffered a series of minor strokes, Thatcher was ordered by doctors to refrain from any public speaking and in the years that followed her health further deteriorated. Her loss of physical and mental capacity was made the focus of the curiously apolitical biopic The Iron Lady. The film was criticised by the Tory right, who preferred to remember Thatcher at her most potent and combative. In a sense they are right. That too, I think, is how we should remember her. Not for what she became once her faculties failed her, but for what she was at the height of her power: an advocate of inequality, a friend to dictators and arms dealers, a champion of power and privilege and a scourge of the poor and vulnerable. A true blue class warrior.

Tom Millsis a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Bath and a co-editor of New Left Project, where this article was first published

1. Cited in Bob Jessop et al, Thatcherism: A Tale of Two Nations (Polity Press, 1988) p.4.

2. Jon Agar, ‘Thatcher, Scientist’, Notes and Records of the Royal Society, Vol.65, No.3, 20 September 2011, 215-232. http://rsnr.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/65/3/215.full

3. ‘Back to the future: the 1970s reconsidered’, Lobster, Winter 1998, Issue 34.

4. Cited in John Welshman, From transmitted deprivation to social exclusion: policy, poverty and parenting (The Policy Press, 2007) p.62.

5. Cited in John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.72.

6. Thatcher: The Path to Power—and Beyond, BBC1, 12 June 1995.

7. Mark Hollingsworth, The Ultimate Spin Doctor: the Life and Fast Times of Tim Bell (1997) p.70

8. James Curran and Colin Leys, ‘Media and the Decline of Liberal Corporatism in Britain’, in James Curran and Myung-Jin Park (eds.), De-Westernizing Media Studies (London: Routledge, 2000) pp. 221-36.

9. Robin Ramsay, ‘Mrs Thatcher, North Sea oil and the hegemony of the City’, Lobster, Issue 27: 1994.

10. Ian Gilmour, Dancing with Dogma (Simon & Schuster, 1992) p.60.

11. Quoted in David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism p.59.

12. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.351.

16. Seumas Milne, The Enemy Within: The Secret War Against the Miners (London: Verso, 1994) p.ix.

17. Stephen Hill, ‘Britain: The Dominant Ideology Thesis after a decade’, In Nicholas Abercrombie, Stephen Hill and Bryan S. Turner (eds.), Dominant Ideologies (London: Unwin Hyman, 1990) p.6.

18. Ivor Crewe, ‘Values: The Crusade that Failed’, in Dennis Kavanagh and Anthony Seldon (eds.), The Thatcher Effect (Oxford University Press, 1989) pp. 239-50.

19. Colin Leys, ‘Still a question of hegemony’, New Left Review, 181, p.127.

20. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.674.

21. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

22. John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (Random House, 2011) p.352.

23. Andrew Gamble, ‘Europe and America’, in Ben Jackson and Robert Saunders (eds.),Making Thatcher’s Britain (Oxford University Press, 2012) p.219.

24. Robin Ramsay, ‘Mrs Thatcher, North Sea oil and the hegemony of the City’, Lobster, Issue 27: 1994.

25. Tory! Tory! Tory! The Exercise of Power, Broadcast on BBC 4 on 11 August 2007, 01:40.

The US has indeed played a large (and usually negative) role in Pakistani politics (and continues to play a large role). But while US imperial intervention is a fact of life, it is not (and has never been) omnipotent or omniscient. Many countries have maneuvered from a position of dependency to one of near-independence. Pakistani nationalism and its supposedly Islamic ideal are neither a necessary result of US intervention, nor its best antithesis. The Pakistani bourgeoisie