Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

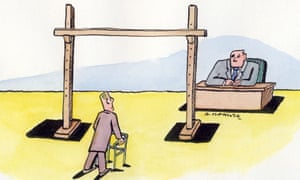

Illustration: Andrzej Krauze

John’s world was torn apart on a Monday morning three weeks ago. First came a text message that read: “We will ring you within 2-3 hours to discuss the outcome of your work capability assessment.” Then the phone went. A “decision maker” at the Department for Work and Pensions told John he’d been judged fit for work – despite his extreme pain, despite all his doctors had said. One of the benefits he needed to live on – employment and support allowance – would stop immediately.

John’s world was torn apart on a Monday morning three weeks ago. First came a text message that read: “We will ring you within 2-3 hours to discuss the outcome of your work capability assessment.” Then the phone went. A “decision maker” at the Department for Work and Pensions told John he’d been judged fit for work – despite his extreme pain, despite all his doctors had said. One of the benefits he needed to live on – employment and support allowance – would stop immediately.

Maximus fit-for-work tests fail mental health patients, says doctor

You may have seen the new film I, Daniel Blake; John is living it. Just like Ken Loach’s character, he’s in his late 50s. He too is in no condition to hold down a full-time job, yet has been told by his own government that he must find work. His story tells you that the nightmare depicted by Loach and the scriptwriter Paul Laverty is neither fictional nor historical – but is being visited right now on our friends, our neighbours and us.

Just like Daniel Blake, John is slowly being crushed between the twin forces of a lumbering, unsympathetic, tick-box, brown-envelope bureaucracy, and a Tory government hellbent on slashing social security. The result is that a disabled man is today being forced to look for jobs that he can’t possibly do, purely to get benefits that won’t even keep a roof above his head.

John doesn’t want his full details made public. “A mauling by the rightwing press would be more than I could bear.” But he’s funny, good on Victorian novels and gentler than I would be in his position. His life has been shaped by an attack he suffered one evening in London 30 years ago. It left him in hospital for three months – and with major injuries to his leg, back and shoulder. They’ve got worse over the years, causing him to give up work about 15 years ago. He recently had a knee replacement; doctors are now contemplating a tricky operation on his spine.

He’s on Tramadol and other heavy-duty painkillers, yet even on the best of days he still has constant pins and needles. At other times, “it’s like someone is stamping on my spine in heavy hobnail boots and smashing nails into my feet and up my leg.” Even on sleeping pills, he hasn’t managed more than three hours a night for over 15 years.

This spring the government decided to test John’s capability for work. I’ve seen the forms myself: in his best exam-boy handwriting, John answers the questions with an almost painful trustingness. No exaggeration, no flinching from admitting that he sometimes wets himself. When it came to assessment day, he took along a local councillor, Denise Jones. At the testing centre run by Maximus – the outsourced provider of assessments – he faced the usual robotic questions about whether he could lift an empty box.

This spring the government decided to test John’s capability for work. I’ve seen the forms myself: in his best exam-boy handwriting, John answers the questions with an almost painful trustingness. No exaggeration, no flinching from admitting that he sometimes wets himself. When it came to assessment day, he took along a local councillor, Denise Jones. At the testing centre run by Maximus – the outsourced provider of assessments – he faced the usual robotic questions about whether he could lift an empty box.

Then came the physical examination. The table was so high John can’t believe he managed to climb on it; Jones says he did, just. Both say the effort cost him visible struggle and pain – and both recall that the “healthcare professional” said she didn’t want to examine him. But the report stripping John of his ESA says it was he who “declined examination”.

That’s not the only discrepancy. The report talks of “lower back pain” – nothing about the legs or feet. It claims he can stay in one place for an hour – no mention of John’s need to move every 10-15 minutes. Other details that John and Jones remember coming up – the hours it takes him just to stretch out in the morning; his habit of falling over; the fact his pain is constant – are simply missing. Jones says in puzzlement: “The report looks like it was just cut and paste.”

I put these and several other detailed points to the DWP last week, but was advised on Monday that John’s was now a “historic claim”. Maximus would need to write to the DWP, then await the details to be posted back – a process that could take about a week. “A giant bureaucracy,” the Maximus spokesman said. If that’s how the head of communications for the company at the centre of this bureaucracy sees things, what hope for the likes of John?

I received instead a “generic response”, which states in part: “We will look into the issues raised in this particular case. All of our healthcare professionals – doctors, nurses and physiotherapists – are fully qualified with a minimum of two years’ postgraduate experience and they receive ongoing training.”

None of this helps John, but it’s not meant to. While awaiting the “reconsideration” of his claim, he’s been to the jobcentre and signed a declaration that he can work for 40 hours a week and commute 90 minutes each way. Both claims are a lie – the stupid, necessary lies John must now tell to get money. Perhaps he should have lied like that in the first place, rather than getting into debt just to keep going. This is for a man who doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke and hasn’t been to the cinema in two years.

His “coach” has lined him up for computer training and a course on how to do a CV. John doesn’t need either, but then this Kafka-meets-IDS bureaucracy in which Britons hand cash to private companies to frustrate other Britons isn’t about what anyone wants or needs. It has more in common with a correctional process – complete with nonsense tasks, the aggressive emphasis on procedure, and the disregard for people. There is only the occasional pinprick of humanity, like the DWP official who at the end of one phone call thanked John “for not shouting at me”.

John’s story is part of a much bigger national process, in which austerity Britain is narrowing down who deserves to live here. On the reject pile go “shirkers”, “benefit tourists” (however many they are), refugees fleeing the bombs of Syria who look insufficiently childlike. And disabled people who, according to the Centre for Welfare Reform, have been hit nine times harder by the Tories’ cuts than has any other group.

Loach’s film ends in defiance. “When you lose your self-respect you’re done for,” says Daniel Blake. But I wonder what it takes to keep your self-respect in a system intent on dehumanising you. I met a couple earlier this year; the husband faced a cut to his disability benefits. Paul Chapman remembered what he’d told his wife, Lisa: “The best thing we can do now is … I’ll clear off and I won’t take my tablets. And it’ll be over then. I won’t be here.” All for the sake of £49 a week.

Denise Jones can see how knackered John is, how often he wells up. “In three weeks, he’s collapsed,” she says. John knows it too. “I don’t want anybody to know how bad this is,” he tells me. “I don’t want anybody to see me so weak. I just feel beaten.” Not for the last time that morning, he breaks down crying.

That’s not the only discrepancy. The report talks of “lower back pain” – nothing about the legs or feet. It claims he can stay in one place for an hour – no mention of John’s need to move every 10-15 minutes. Other details that John and Jones remember coming up – the hours it takes him just to stretch out in the morning; his habit of falling over; the fact his pain is constant – are simply missing. Jones says in puzzlement: “The report looks like it was just cut and paste.”

I put these and several other detailed points to the DWP last week, but was advised on Monday that John’s was now a “historic claim”. Maximus would need to write to the DWP, then await the details to be posted back – a process that could take about a week. “A giant bureaucracy,” the Maximus spokesman said. If that’s how the head of communications for the company at the centre of this bureaucracy sees things, what hope for the likes of John?

I received instead a “generic response”, which states in part: “We will look into the issues raised in this particular case. All of our healthcare professionals – doctors, nurses and physiotherapists – are fully qualified with a minimum of two years’ postgraduate experience and they receive ongoing training.”

None of this helps John, but it’s not meant to. While awaiting the “reconsideration” of his claim, he’s been to the jobcentre and signed a declaration that he can work for 40 hours a week and commute 90 minutes each way. Both claims are a lie – the stupid, necessary lies John must now tell to get money. Perhaps he should have lied like that in the first place, rather than getting into debt just to keep going. This is for a man who doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke and hasn’t been to the cinema in two years.

His “coach” has lined him up for computer training and a course on how to do a CV. John doesn’t need either, but then this Kafka-meets-IDS bureaucracy in which Britons hand cash to private companies to frustrate other Britons isn’t about what anyone wants or needs. It has more in common with a correctional process – complete with nonsense tasks, the aggressive emphasis on procedure, and the disregard for people. There is only the occasional pinprick of humanity, like the DWP official who at the end of one phone call thanked John “for not shouting at me”.

John’s story is part of a much bigger national process, in which austerity Britain is narrowing down who deserves to live here. On the reject pile go “shirkers”, “benefit tourists” (however many they are), refugees fleeing the bombs of Syria who look insufficiently childlike. And disabled people who, according to the Centre for Welfare Reform, have been hit nine times harder by the Tories’ cuts than has any other group.

Loach’s film ends in defiance. “When you lose your self-respect you’re done for,” says Daniel Blake. But I wonder what it takes to keep your self-respect in a system intent on dehumanising you. I met a couple earlier this year; the husband faced a cut to his disability benefits. Paul Chapman remembered what he’d told his wife, Lisa: “The best thing we can do now is … I’ll clear off and I won’t take my tablets. And it’ll be over then. I won’t be here.” All for the sake of £49 a week.

Denise Jones can see how knackered John is, how often he wells up. “In three weeks, he’s collapsed,” she says. John knows it too. “I don’t want anybody to know how bad this is,” he tells me. “I don’t want anybody to see me so weak. I just feel beaten.” Not for the last time that morning, he breaks down crying.