12 Aug 2015

If China really is trying to drive down its currency in any meaningful way to gain trade advantage, the world faces an extremely dangerous moment.

Such desperate behaviour would send a deflationary shock through a global economy already reeling from near recession earlier this year, and would risk a repeat of East Asia's currency crisis in 1998 on a larger planetary scale.

China's fixed investment reached $5 trillion last year, matching the whole of Europe and North America combined. This is the root cause of chronic overcapacity worldwide, from shipping, to steel, chemicals and solar panels.

A Chinese devaluation would export yet more of this excess supply to the rest of us. It is one thing to do this when global trade is expanding: it amounts to beggar-thy-neighbour currency warfare to do so in a zero-sum world with no growth at all in shipping volumes this year.

It is little wonder that the first whiff of this mercantilist threat has set off an August storm, ripping through global bourses. The Bloomberg commodity index has crashed to a 13-year low.

Europe and America have failed to build up adequate safety buffers against a fresh wave of imported deflation. Core prices are rising at a rate of barely 1pc on both sides of the Atlantic, a full six years into a mature economic cycle.

One dreads to think what would happen if we tip into a global downturn in these circumstances, with interest rates still at zero, quantitative easing played out, and aggregate debt levels 30 percentage points of GDP higher than in 2008.

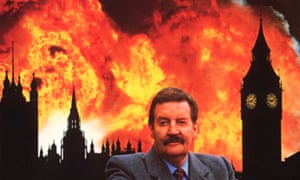

"The world economy is sailing across the ocean without any lifeboats to use in case of emergency," said Stephen King from HSBC in a haunting reportin May.

Whether or not Beijing sees matters in this light, it knows that the US Congress would react very badly to any sign of currency warfare by a country that racked up a record trade surplus of $137bn in second quarter, an annual pace above 5pc of GDP. Only deficit states can plausibly justify resorting to this game.

Senators Schumer, Casey, Grassley, and Graham have all lined up to accuse Beijing of currency manipulation, a term that implies retaliatory sanctions under US trade law.

Any political restraint that Congress might once have felt is being eroded fast by evidence of Chinese airstrips and artillery on disputed reefs in the South China Sea, just off the Philippines.

It is too early to know for sure whether China has in fact made a conscious decision to devalue. Bo Zhuang from Trusted Sources said there is a "tug-of-war" within the Communist Party.

All the central bank (PBOC) has done so far is to switch from a dollar peg to a managed float. This is a step closer towards a free market exchange, and has been welcomed by the US Treasury and the International Monetary Fund.

The immediate effect was a 1.84pc fall in the yuan against the dollar on Tuesday, breathlessly described as the biggest one-day move since 1994. The PBOC said it was a merely "one-off" technical adjustment.

If so, one might also assume that the PBOC would defend the new line at 6.32 to drive home the point. What is faintly alarming is that the central bank failed to do so, letting the currency slide a further 1.6pc on Wednesday before reacting.

The PBOC put out a soothing statement, insisting that "currently there is no basis for persistent depreciation" of the yuan and that the economy is in any case picking up. So take your pick: conspiracy or cock-up.

The proof will now be in the pudding. The PBOC has $3.65 trillion reserves to prevent any further devaluation for the time being. If it does not do so, we may legitimately suspect that the State Council is in charge and has opted for covert currency warfare.

Personally, I doubt that this is the start of a long slippery slide. The risks are too high. Chinese companies have borrowed huge sums in US dollars on off-shore markets to circumvent lending curbs at home, and these are typically the weakest firms shut off from China's banking system.

Hans Redeker from Morgan Stanley says short-term dollar liabilities reached $1.3 trillion earlier this year. "This is 9.5pc of Chinese GDP. When short-term foreign debt reaches this level in emerging markets it is a perfect indicator of coming stress. It is exactly what we saw in the Asian crisis in the 1990s," he said.

Devaluation would risk setting off serious capital flight, far beyond the sort of outflows seen so far - with estimates varying from $400bn to $800bn over the last five quarters.

This could spin out of control easily if markets suspect that Beijing is itself fanning the flames. While the PBOC could counter outflows by running down reserves - as it is already doing to a degree, at a pace of $15bn a month - such a policy entails automatic monetary tightening and might make matters worse.

The slowdown in China is not yet serious enough to justify such a risk. True, the trade-weighted exchange rate has soared 22pc since mid-2012, the result of being strapped to a rocketing dollar at the wrong moment. The yuan is up 60pc against the Japanese yen.

This loss of competitiveness has been painful - and is getting worse as the shrinking supply of migrant labour from the countryside pushes up wages - but it was not the chief cause of the crunch in the first half of the year.

The economy hit a brick wall because monetary and fiscal policy were too tight. The authorities failed to act as falling inflation pushed one-year borrowing costs in real terms from zero in 2011 to 5pc by the end of 2014.

They also failed to anticipate a “fiscal cliff” earlier this year as official revenue from land sales collapsed, and local governments were prohibited from bank borrowing -- understandably perhaps given debts of $5 trillion, on some estimates.

The calibrated deleveraging by premier Li Keqiang simply went too far. He has since reversed course. The local government bond market is finally off the ground, issuing $205bn of new debt between May and July. This is serious fiscal stimulus.

Nomura says monetary policy is now as loose as in the depths of the post-Lehman crisis. Its 'growth surprise index' for China touched bottom in May and is now signalling a “strong rebound”.

Capital Economics said bank loans jumped to 15.5pc in June, the fastest pace since 2012. "There are already signs that policy easing is gaining traction," it said.

It is worth remembering that the authorities are no longer targeting headline growth. Their lode star these days is employment, a far more relevant gauge for the survival of the Communist regime. On this score, there is no great drama. The economy generated 7.2m extra jobs in the first half half of 2015, well ahead of the 10m annual target.

Few dispute that China is in trouble. Credit has been stretched to the limit and beyond. The jump in debt from 120pc to 260pc of GDP in seven years is unprecedented in any major economy in modern times.

For sheer intensity of credit excess, it is twice the level of Japan's Nikkei bubble in the late 1980s, and I doubt that it will end any better. At least Japan was already rich when it let rip. China faces much the same demographic crisis before it crosses the development threshold.

It is in any case wrestling with an impossible contradiction: aspiring to hi-tech growth on the economic cutting edge, yet under top-down Communist party control and spreading repression. That way lies the middle income trap, the curse of all authoritarian regimes that fail to reform in time.

Yet this is a story for the next fifteen years. The Communist Party has not yet run out of stimulus and is clearly deploying the state banking system to engineer yet another mini-cycle right now. One day China will pull the lever and nothing will happen. We are not there yet.