Peter Harrison in The Wire.In

In 1966, just over 50 years ago, the distinguished Canadian-born anthropologist Anthony Wallace confidently predicted the global demise of religion at the hands of an advancing science: ‘belief in supernatural powers is doomed to die out, all over the world, as a result of the increasing adequacy and diffusion of scientific knowledge’. Wallace’s vision was not exceptional. On the contrary, the modern social sciences, which took shape in 19th-century western Europe, took their own recent historical experience of secularisation as a universal model. An assumption lay at the core of the social sciences, either presuming or sometimes predicting that all cultures would eventually converge on something roughly approximating secular, Western, liberal democracy. Then something closer to the opposite happened.

Not only has secularism failed to continue its steady global march but countries as varied as Iran, India, Israel, Algeria and Turkey have either had their secular governments replaced by religious ones, or have seen the rise of influential religious nationalist movements. Secularisation, as predicted by the social sciences, has failed.

To be sure, this failure is not unqualified. Many Western countries continue to witness decline in religious belief and practice. The most recent census data released in Australia, for example, shows that 30 per cent of the population identify as having ‘no religion’, and that this percentage is increasing. International surveys confirm comparatively low levels of religious commitment in western Europe and Australasia. Even the United States, a long-time source of embarrassment for the secularisation thesis, has seen a rise in unbelief.

The percentage of atheists in the US now sits at an all-time high (if ‘high’ is the right word) of around 3 per cent. Yet, for all that, globally, the total number of people who consider themselves to be religious remains high, and demographic trends suggest that the overall pattern for the immediate future will be one of religious growth. But this isn’t the only failure of the secularisation thesis.

Scientists, intellectuals and social scientists expected that the spread of modern science would drive secularisation – that science would be a secularising force. But that simply hasn’t been the case. If we look at those societies where religion remains vibrant, their key common features are less to do with science, and more to do with feelings of existential security and protection from some of the basic uncertainties of life in the form of public goods. A social safety net might be correlated with scientific advances but only loosely, and again the case of the US is instructive. The US is arguably the most scientifically and technologically advanced society in the world, and yet at the same time the most religious of Western societies. As the British sociologist David Martin concluded in The Future of Christianity (2011): ‘There is no consistent relation between the degree of scientific advance and a reduced profile of religious influence, belief and practice.’

The story of science and secularisation becomes even more intriguing when we consider those societies that have witnessed significant reactions against secularist agendas. India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru championed secular and scientific ideals, and enlisted scientific education in the project of modernisation. Nehru was confident that Hindu visions of a Vedic past and Muslim dreams of an Islamic theocracy would both succumb to the inexorable historical march of secularisation. ‘There is only one-way traffic in Time,’ he declared. But as the subsequent rise of Hindu and Islamic fundamentalism adequately attests, Nehru was wrong. Moreover, the association of science with a secularising agenda has backfired, with science becoming a collateral casualty of resistance to secularism.

Turkey provides an even more revealing case. Like most pioneering nationalists, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish republic, was a committed secularist. Atatürk believed that science was destined to displace religion. In order to make sure that Turkey was on the right side of history, he gave science, in particular evolutionary biology, a central place in the state education system of the fledgling Turkish republic.

As a result, evolution came to be associated with Atatürk’s entire political programme, including secularism. Islamist parties in Turkey, seeking to counter the secularist ideals of the nation’s founders, have also attacked the teaching of evolution. For them, evolution is associated with secular materialism. This sentiment culminated in the decision this June to remove the teaching of evolution from the high-school classroom. Again, science has become a victim of guilt by association.

The US represents a different cultural context, where it might seem that the key issue is a conflict between literal readings of Genesis and key features of evolutionary history. But in fact, much of the creationist discourse centres on moral values. In the US case too, we see anti-evolutionism motivated at least in part by the assumption that evolutionary theory is a stalking horse for secular materialism and its attendant moral commitments. As in India and Turkey, secularism is actually hurting science.

In brief, global secularisation is not inevitable and, when it does happen, it is not caused by science. Further, when the attempt is made to use science to advance secularism, the results can damage science. The thesis that ‘science causes secularisation’ simply fails the empirical test, and enlisting science as an instrument of secularisation turns out to be poor strategy. The science and secularism pairing is so awkward that it raises the question: why did anyone think otherwise?

Historically, two related sources advanced the idea that science would displace religion. First, 19th-century progressivist conceptions of history, particularly associated with the French philosopher Auguste Comte, held to a theory of history in which societies pass through three stages – religious, metaphysical and scientific (or ‘positive’). Comte coined the term ‘sociology’ and he wanted to diminish the social influence of religion and replace it with a new science of society. Comte’s influence extended to the ‘young Turks’ and Atatürk.

The 19th century also witnessed the inception of the ‘conflict model’ of science and religion. This was the view that history can be understood in terms of a ‘conflict between two epochs in the evolution of human thought – the theological and the scientific’. This description comes from Andrew Dickson White’s influential A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896), the title of which nicely encapsulates its author’s general theory. White’s work, as well as John William Draper’s earlier History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science (1874), firmly established the conflict thesis as the default way of thinking about the historical relations between science and religion. Both works were translated into multiple languages. Draper’s History went through more than 50 printings in the US alone, was translated into 20 languages and, notably, became a bestseller in the late Ottoman empire, where it informed Atatürk’s understanding that progress meant science superseding religion.

Today, people are less confident that history moves through a series of set stages toward a single destination. Nor, despite its popular persistence, do most historians of science support the idea of an enduring conflict between science and religion. Renowned collisions, such as the Galileo affair, turned on politics and personalities, not just science and religion. Darwin had significant religious supporters and scientific detractors, as well as vice versa. Many other alleged instances of science-religion conflict have now been exposed as pure inventions. In fact, contrary to conflict, the historical norm has more often been one of mutual support between science and religion. In its formative years in the 17th century, modern science relied on religious legitimation. During the 18th and 19th centuries, natural theology helped to popularise science.

The conflict model of science and religion offered a mistaken view of the past and, when combined with expectations of secularisation, led to a flawed vision of the future. Secularisation theory failed at both description and prediction. The real question is why we continue to encounter proponents of science-religion conflict. Many are prominent scientists. It would be superfluous to rehearse Richard Dawkins’s musings on this topic, but he is by no means a solitary voice. Stephen Hawking thinks that ‘science will win because it works’; Sam Harris has declared that ‘science must destroy religion’; Stephen Weinberg thinks that science has weakened religious certitude; Colin Blakemore predicts that science will eventually make religion unnecessary. Historical evidence simply does not support such contentions. Indeed, it suggests that they are misguided.

So why do they persist? The answers are political. Leaving aside any lingering fondness for quaint 19th-century understandings of history, we must look to the fear of Islamic fundamentalism, exasperation with creationism, an aversion to alliances between the religious Right and climate-change denial, and worries about the erosion of scientific authority. While we might be sympathetic to these concerns, there is no disguising the fact that they arise out of an unhelpful intrusion of normative commitments into the discussion. Wishful thinking – hoping that science will vanquish religion – is no substitute for a sober assessment of present realities. Continuing with this advocacy is likely to have an effect opposite to that intended.

Religion is not going away any time soon, and science will not destroy it. If anything, it is science that is subject to increasing threats to its authority and social legitimacy. Given this, science needs all the friends it can get. Its advocates would be well advised to stop fabricating an enemy out of religion, or insisting that the only path to a secure future lies in a marriage of science and secularism.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label secular. Show all posts

Showing posts with label secular. Show all posts

Sunday, 15 October 2017

Friday, 14 April 2017

Faith still a potent presence in Western politics

Harriet Sherwood in The Guardian

Faith remains a potent presence at the highest level of UK politics despite a growing proportion of the country’s population defining themselves as non-religious, according to the author of a new book examining the faith of prominent politicians.

Nick Spencer, research director of the Theos thinktank and the lead author of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, uses the example that all but one of Britain’s six prime ministers in the past four decades have been practising Christians to make his point.

The book examines the faith of 24 prominent politicians, mostly in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. “The presence and prevalence of Christian leaders, not least in some of the world’s most secular, plural and ‘modern’ countries, remains noteworthy. The idea that ‘secularisation’ would purge politics of religious commitment is surely misguided,” it concludes.

It includes “theo-political biographies” of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar’s daughter who has spoken publicly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her predecessors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Only John Major is absent from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer writes that May is a “politician with strong views rather than a strong ideology, and those views were seemingly shaped by her Christian upbringing and faith. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, ‘a moral backing to what I do, and I would hope that the decisions I take are taken on the basis of my faith’.”

May told Desert Island Discs in 2014 that Christianity had helped to frame her thinking but it was “right that we don’t flaunt these things here in British politics”. According to Spencer, “in this regard at very least, May practises what she preaches”.

However, the prime minister’s apparent reticence did not stop her lambasting Cadbury’s and the National Trust this month over their supposed downgrading of the word Easter in promotional materials and packaging.

Elsewhere, the book looks at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European leaders, three Australian prime ministers and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five leaders from other countries – including Nelson Mandela – complete the list.

The “great secular hope” was that religion would fade out of the political landscape, Spencer writes. But “the last 40 years have turned out somewhat different”, with the emergence of political Islam, the strength of Catholicism in central and south America and the explosion of Pentecostalism in the global south.

Even in the west, “Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so,” he says.

But Spencer told the Guardian: “There is no one size fits all, politically. You don’t find them clustering on the political spectrum.”

At the rightwing end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the president of Paraguay between 2008 and 2012, a prominent Catholic “bishop of the poor”, liberation theologist and part of a wave of leftwing leaders in Latin America.

There were also significant differences in the political contexts in which Christian politicians were operating, Spencer said. “There are places where you stand to make a lot of political capital by talking about your faith – such as the US or Russia.

“But in countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-sceptical, politicians stand to lose political capital. No politician in the UK or France talks about their faith in order to win over the electorate.”

Tony Blair in 2001. Photograph: Jonathan Evans/Reuters

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

After he left Downing Street, Blair spoke of the difficulties of talking about “religious faith in our political system. If you are in the American political system or others then you can talk about religious faith and people say ‘yes, that’s fair enough’ and it is something they respond to quite naturally. You talk about it in our system and, frankly, people do think you’re a nutter.”

Although Blair’s faith reportedly shaped all his key policy decisions in office, the same was not true of all politicians, said Spencer. “There are some politicians for whom faith has shaped politics, and others for whom you can be more confident that politics are shaping faith. Trump is an example of that,” he said.

According to the chapter on Trump – a late addition to the book – the president “is not known for his interest in theology, the church or religion. His statements about faith, not least his own faith, have been infrequent and vague. And yet, Trump is insistent that he believes in God, loves the Bible and has a good relationship with the church … Simply to dismiss Trump’s faith talk would be to dismiss Trump, and 2016 showed that that is a mistake”.

Leaders’ faith

Theresa May Daughter of an Anglican vicar, the British prime minister goes to church most Sundays and has said her Christian faith is “part of who I am and therefore how I approach things ... [it] helps to frame my thinking and my approach”.

Vladimir Putin The Russian president has increasingly presented himself as a man of serious personal faith, which some suggest is connected to a nationalist agenda. He reportedly prays daily in a small Orthodox chapel next to the presidential office.

Angela Merkel The German chancellor is a serious Christian believer but one whose faith is very private. “I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life,” she told an interviewer in 2012.

Fernando Lugo The former president of Paraguay was also a prominent Catholic bishop, a champion of the poor and a leading advocate of liberation theology. He urged “defending the gospel values of truth against so many lies, justice against so much injustice, and peace against so much violence”.

Viktor Orbán A relatively recent convert to faith, the Hungarian prime minister frequently invokes the need to defend “Christian Europe” against Muslim migrants. “Christianity is not only a religion, but is also a culture on which we have built a whole civilisation,” he said in 2014.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf The president of Liberia and a Nobel peace laureate, Sirleaf was brought up in a devout family and has frequently appealed for “God’s help and guidance” during her 10 years as head of state. In a 2010 speech, she described religion and spirituality as “the cornerstone of hope, faith and love for all peoples and races”.

Faith remains a potent presence at the highest level of UK politics despite a growing proportion of the country’s population defining themselves as non-religious, according to the author of a new book examining the faith of prominent politicians.

Nick Spencer, research director of the Theos thinktank and the lead author of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, uses the example that all but one of Britain’s six prime ministers in the past four decades have been practising Christians to make his point.

The book examines the faith of 24 prominent politicians, mostly in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. “The presence and prevalence of Christian leaders, not least in some of the world’s most secular, plural and ‘modern’ countries, remains noteworthy. The idea that ‘secularisation’ would purge politics of religious commitment is surely misguided,” it concludes.

It includes “theo-political biographies” of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar’s daughter who has spoken publicly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her predecessors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Only John Major is absent from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer writes that May is a “politician with strong views rather than a strong ideology, and those views were seemingly shaped by her Christian upbringing and faith. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, ‘a moral backing to what I do, and I would hope that the decisions I take are taken on the basis of my faith’.”

May told Desert Island Discs in 2014 that Christianity had helped to frame her thinking but it was “right that we don’t flaunt these things here in British politics”. According to Spencer, “in this regard at very least, May practises what she preaches”.

However, the prime minister’s apparent reticence did not stop her lambasting Cadbury’s and the National Trust this month over their supposed downgrading of the word Easter in promotional materials and packaging.

Elsewhere, the book looks at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European leaders, three Australian prime ministers and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five leaders from other countries – including Nelson Mandela – complete the list.

The “great secular hope” was that religion would fade out of the political landscape, Spencer writes. But “the last 40 years have turned out somewhat different”, with the emergence of political Islam, the strength of Catholicism in central and south America and the explosion of Pentecostalism in the global south.

Even in the west, “Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so,” he says.

But Spencer told the Guardian: “There is no one size fits all, politically. You don’t find them clustering on the political spectrum.”

At the rightwing end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the president of Paraguay between 2008 and 2012, a prominent Catholic “bishop of the poor”, liberation theologist and part of a wave of leftwing leaders in Latin America.

There were also significant differences in the political contexts in which Christian politicians were operating, Spencer said. “There are places where you stand to make a lot of political capital by talking about your faith – such as the US or Russia.

“But in countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-sceptical, politicians stand to lose political capital. No politician in the UK or France talks about their faith in order to win over the electorate.”

Tony Blair in 2001. Photograph: Jonathan Evans/Reuters

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

After he left Downing Street, Blair spoke of the difficulties of talking about “religious faith in our political system. If you are in the American political system or others then you can talk about religious faith and people say ‘yes, that’s fair enough’ and it is something they respond to quite naturally. You talk about it in our system and, frankly, people do think you’re a nutter.”

Although Blair’s faith reportedly shaped all his key policy decisions in office, the same was not true of all politicians, said Spencer. “There are some politicians for whom faith has shaped politics, and others for whom you can be more confident that politics are shaping faith. Trump is an example of that,” he said.

According to the chapter on Trump – a late addition to the book – the president “is not known for his interest in theology, the church or religion. His statements about faith, not least his own faith, have been infrequent and vague. And yet, Trump is insistent that he believes in God, loves the Bible and has a good relationship with the church … Simply to dismiss Trump’s faith talk would be to dismiss Trump, and 2016 showed that that is a mistake”.

Leaders’ faith

Theresa May Daughter of an Anglican vicar, the British prime minister goes to church most Sundays and has said her Christian faith is “part of who I am and therefore how I approach things ... [it] helps to frame my thinking and my approach”.

Vladimir Putin The Russian president has increasingly presented himself as a man of serious personal faith, which some suggest is connected to a nationalist agenda. He reportedly prays daily in a small Orthodox chapel next to the presidential office.

Angela Merkel The German chancellor is a serious Christian believer but one whose faith is very private. “I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life,” she told an interviewer in 2012.

Fernando Lugo The former president of Paraguay was also a prominent Catholic bishop, a champion of the poor and a leading advocate of liberation theology. He urged “defending the gospel values of truth against so many lies, justice against so much injustice, and peace against so much violence”.

Viktor Orbán A relatively recent convert to faith, the Hungarian prime minister frequently invokes the need to defend “Christian Europe” against Muslim migrants. “Christianity is not only a religion, but is also a culture on which we have built a whole civilisation,” he said in 2014.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf The president of Liberia and a Nobel peace laureate, Sirleaf was brought up in a devout family and has frequently appealed for “God’s help and guidance” during her 10 years as head of state. In a 2010 speech, she described religion and spirituality as “the cornerstone of hope, faith and love for all peoples and races”.

Sunday, 5 March 2017

Wednesday, 26 October 2016

Sunday, 22 November 2015

Don’t ignore the saner voices of moderate Muslims

SA Aiyar in The Times of India

There is much in common between those who hit Paris last week and Mumbai on 26/11. Let nobody pretend, like elements of the left, that Paris was just revenge against Western imperialism. ISIS aims to become the biggest imperialist of all, re-creating the ancient Islamic empire from Portugal to China. The Ottoman caliphate once came close to conquering the whole of Europe, and ISIS would like to finish the job. It claims a divine right to kill those who come in the way — Arabs, Jews, Americans, Europeans, Indians or anyone else.

UP home minister Azam Khan outraged many by making excuses for the Paris killings. He said this was a reaction to the actions of global superpowers like America and Russia. “History will decide who is the terrorist. Killing innocents whether in Syria or Paris is a highly deplorable act… But if you created such a situation, you have to face the backlash too.”

This determination to justify the attack, while grudgingly condemning it, is hypocritical communalism. It has parallels with the grudging criticism by BJP leaders of the lynching of the Dadri Muslim accused of eating beef. Tarun Vijay wrote that the lynching would indeed be terrible if it turned out that he had only eaten mutton. Culture minister Mahesh Sharma claims it was just “an accident.” Former MLA Nawab Singh Nagar said those who dared hurt the feelings of the dominant Thakurs should realize the consequences, and claimed that the murderous mob consisted of “innocent children” below 15 years of age. Srichand Sharma said violence was inevitable if Muslims disrespected Hindu sentiments.

The inability of these BJP leaders to condemn the lynching outright is matched by Azam Khan’s inability to condemn the Paris attackers outright. Communalists cherry-pick events from history to claim they are victims, with the right to vengeful retribution. Sorry, but groups across the world have been both attackers and victims. Through history, imperial conquest, killing and loot was considered great (hence Alexander the Great, or Peter the Great). Modern notions of civil rights, secularism and nationhood did not exist. Might was right, indeed greatness.

And so there were Muslims who conquered and plundered, and other Muslims who were at the receiving end. Christian conquerors created large empires by the sword, and were in turn subjugated by others. Hindu, Chinese, Mongol, Arab and African kings killed and looted for personal aggrandizement, and in turn were killed and looted.

Communalists harp on events in which they were victims, ignoring others where they were victimizers. ISIS and Azam Khan repeat the victimhood theme of Muslims in the 20th century, complaining of being bombed and dominated by the West, and claiming that revenge is both justifiable and inevitable. They are unable to see themselves also as victimizers who slaughtered and looted for centuries, from Portugal to China. Nor will they accept that victims from Portugal to China have a right to revenge.

Right message: Last week’s fatwa against ISIS signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis deserved more coverage

Right message: Last week’s fatwa against ISIS signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis deserved more coverage

A sane, safe society is not possible if every community wants to avenge events of the past. Every community needs to accept that it has been both a victimizer and victim, and leave the past behind. Some communities have succeeded in doing this — notably Germany after World War II — and that has been the basis for civilized progress. The contrast with ISIS could not be greater.

While the media has rightly focused on Azam Khan, they have ignored the much saner response of moderate Muslims. It’s wrong to constantly highlight communal Muslims and downplay nationalist ones.

TOI last Wednesday reported “the biggest fatwa ever” against ISIS, signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis. The fatwa, which condemned ISIS categorically as “inhuman” and “un-lslamic”, has been forwarded by Abdur Rahman Anjaria of the Islamic Defence Cybercell to the UN, several foreign governments and the Prime Minister’s Office. Anjaria says the fatwa is the biggest ever initiative by Indian ulema to reject the dangerous ideology of ISIS, which “has disgraced the name of Allah and the Prophet….It is the duty of every Muslim to join the fight to defeat it.”

I think this news should have been on page one in every newspaper. Instead it was hidden in the inside pages of the Times of India. So was another small report on a protest meeting in Delhi by the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, to condemn the strikes in Paris, Turkey and Lebanon in the name of Islam. Without naming Azam Khan, its general secretary, Maulana Madani, said “We completely dismiss the action-reaction theory propounded by some persons.”

Prime Minister Modi needs to highlight and cite such moderate views. It’s not enough to say India needs social harmony. It’s also necessary to give kudos to those who promote that moderation.

There is much in common between those who hit Paris last week and Mumbai on 26/11. Let nobody pretend, like elements of the left, that Paris was just revenge against Western imperialism. ISIS aims to become the biggest imperialist of all, re-creating the ancient Islamic empire from Portugal to China. The Ottoman caliphate once came close to conquering the whole of Europe, and ISIS would like to finish the job. It claims a divine right to kill those who come in the way — Arabs, Jews, Americans, Europeans, Indians or anyone else.

UP home minister Azam Khan outraged many by making excuses for the Paris killings. He said this was a reaction to the actions of global superpowers like America and Russia. “History will decide who is the terrorist. Killing innocents whether in Syria or Paris is a highly deplorable act… But if you created such a situation, you have to face the backlash too.”

This determination to justify the attack, while grudgingly condemning it, is hypocritical communalism. It has parallels with the grudging criticism by BJP leaders of the lynching of the Dadri Muslim accused of eating beef. Tarun Vijay wrote that the lynching would indeed be terrible if it turned out that he had only eaten mutton. Culture minister Mahesh Sharma claims it was just “an accident.” Former MLA Nawab Singh Nagar said those who dared hurt the feelings of the dominant Thakurs should realize the consequences, and claimed that the murderous mob consisted of “innocent children” below 15 years of age. Srichand Sharma said violence was inevitable if Muslims disrespected Hindu sentiments.

The inability of these BJP leaders to condemn the lynching outright is matched by Azam Khan’s inability to condemn the Paris attackers outright. Communalists cherry-pick events from history to claim they are victims, with the right to vengeful retribution. Sorry, but groups across the world have been both attackers and victims. Through history, imperial conquest, killing and loot was considered great (hence Alexander the Great, or Peter the Great). Modern notions of civil rights, secularism and nationhood did not exist. Might was right, indeed greatness.

And so there were Muslims who conquered and plundered, and other Muslims who were at the receiving end. Christian conquerors created large empires by the sword, and were in turn subjugated by others. Hindu, Chinese, Mongol, Arab and African kings killed and looted for personal aggrandizement, and in turn were killed and looted.

Communalists harp on events in which they were victims, ignoring others where they were victimizers. ISIS and Azam Khan repeat the victimhood theme of Muslims in the 20th century, complaining of being bombed and dominated by the West, and claiming that revenge is both justifiable and inevitable. They are unable to see themselves also as victimizers who slaughtered and looted for centuries, from Portugal to China. Nor will they accept that victims from Portugal to China have a right to revenge.

Right message: Last week’s fatwa against ISIS signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis deserved more coverage

Right message: Last week’s fatwa against ISIS signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis deserved more coverageA sane, safe society is not possible if every community wants to avenge events of the past. Every community needs to accept that it has been both a victimizer and victim, and leave the past behind. Some communities have succeeded in doing this — notably Germany after World War II — and that has been the basis for civilized progress. The contrast with ISIS could not be greater.

While the media has rightly focused on Azam Khan, they have ignored the much saner response of moderate Muslims. It’s wrong to constantly highlight communal Muslims and downplay nationalist ones.

TOI last Wednesday reported “the biggest fatwa ever” against ISIS, signed by 1,070 Indian imams and muftis. The fatwa, which condemned ISIS categorically as “inhuman” and “un-lslamic”, has been forwarded by Abdur Rahman Anjaria of the Islamic Defence Cybercell to the UN, several foreign governments and the Prime Minister’s Office. Anjaria says the fatwa is the biggest ever initiative by Indian ulema to reject the dangerous ideology of ISIS, which “has disgraced the name of Allah and the Prophet….It is the duty of every Muslim to join the fight to defeat it.”

I think this news should have been on page one in every newspaper. Instead it was hidden in the inside pages of the Times of India. So was another small report on a protest meeting in Delhi by the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, to condemn the strikes in Paris, Turkey and Lebanon in the name of Islam. Without naming Azam Khan, its general secretary, Maulana Madani, said “We completely dismiss the action-reaction theory propounded by some persons.”

Prime Minister Modi needs to highlight and cite such moderate views. It’s not enough to say India needs social harmony. It’s also necessary to give kudos to those who promote that moderation.

Tuesday, 3 February 2015

Can Sufism save Sind?

Suleman Akhtar in The Dawn

Sindh is under attack. The land of Shah Latif bleeds again. The seven queens of Shah Latif’s Shah Jo Risalo – Marui, Sassui, Noori, Sorath, Lilan, Sohni, and Momal – have put on black cloaks and they mourn. The troubles and tribulations are not new for the queens.

After the sack of Delhi, Nadir Shah (Shah of Iran), invaded Sindh and imprisoned the then Sindhi ruler Noor Mohammad Kalhoro in Umarkot fort. Shah Latif captured it in the yearning of Marui for her beloved land when she was locked up in the same Umarkot fort.

If looking to my native land

with longing I expire;

My body carry home, that I

may rest in desert-stand;

My bones if Malir reach, at end,

though dead, I'll live again.

(Sur Marui, XXVIII, Shah Jo Risalo)

The attack on the central Imambargah in Shikarpur is as ominous in many ways as it is horrendous and tragic.

The Sufi ethos of Sindh has long been cherished as the panacea for burgeoning extremism in Pakistan. Sufism has been projected lately as an effective alternative to rising fundamentalism in Muslim societies not only by the Pakistani liberal intelligentsia but also by some Western think-tanks and NGOs.

But the question is, how effective as an ideology can Sufism be in its role in contemporary societies?

To begin with, Sufism is not a monolithic ideology.

There are several strains within Sufism that are in total opposition to each other, thus culminating into totally opposite worldviews. The most important of them is chasm between Wahdat al-Wajud (unity of existence) and Wahdat al-Shahud (unity of phenomenon).

The former professes that there is only One real being not separated from His creation, and thus God runs through everything. While Wahdat al-Shahud holds that God is separated from His creation.

While the distinction between the two might seem purely polemical, it actually leads to two entirely opposite logical conclusions.

Wahdat al-Wajud sees God running through everything. Thus apparent differences between different religions and school of thoughts vanish at once. In diversity, there lies a unity thus paving way to acceptance of any creed, irrespective of its religious foundations.

Ibn al-Arbi was the first to lay the theoretical foundations of Wahdat al-Wajud and introduce it to the Muslim world.

On the other hand, the Wahdat al-Shahud school of thought was developed and propagated by Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, who rose to counter the secular excesses of Akbar. He pronounced Ibn al-Arbi as Kafir and went on deconstructing what he deemed as heresies.

Wahdat al-Shahud in its sociopolitical context leads to separation and confrontation. The staunch anti-Hindu and anti-Shia views of Ahmed Sirhindi are just a logical consequence of this school of thought. Ahmed Sirhindi is one of the few Sufis mentioned in Pakistani textbooks.

Historically, Sufis in today’s Pakistan have belonged to four Sufi orders: Qadriah, Chishtiah, Suharwardiah, and Naqshbandiah.

It is also interesting to note that not all of these Sufi orders have been historically anti-establishment.

While Sufis who belonged to the Chishtiah and Qadriah orders always kept a distance from emperors in Delhi and kept voicing for the people, the Suharwardia order has always been close to the power centres. Bahauddin Zikria of the Suharwardiah order enjoyed close relations with the Darbar and after that leaders of this order have always sided with the ruler (either Mughals or British) against the will of the people.

Sufism in the subcontinent in general and Sindh in particular, emerged and evolved as a formidable opposition to the King and Mullah/Pundit nexus. Not only did it give voice to the voiceless victims of religious fanaticism, but also challenged the established political order.

To quote Marx it was ‘the soul of soulless conditions’.

A case-in-point is Shah Inayat of Jhok Sharif, who led a popular peasant revolt in Sindh and was executed afterwards. Shah Latif wrote a nameless eulogy of Shah Inayat in Shah Jo Risalo.

However, the socio-political conditions that gave rise to Sufism in the subcontinent are not present anymore. The resurrection of Sufism as a potent resistance ideology is difficult if not impossible. Sufis emerged from ashes of civilizational mysticism, independent of organised religion and political powers.

Today, however, the so-called centres of Sufism known as Khanqahs are an integral part of both the contemporary political elite and the all-powerful clergy. On intellectual front self-proclaimed proponents of contemporary Sufism – Qudratullah Shahab, Ashfaq Ahmad, Mumtaz Mufti, et al – have been a part of state apparatus and ideology in one form or another.

Sufism is necessarily a humanist and universal ideology. It is next to impossible to confine it to the boundaries of modern nation states and ideological states in particular, which thrive on an exclusivist ideology.

Mansoor al-Hallaj travelled extensively throughout Sindh. His famous proclamation Ana ‘al Haq (I am the truth) is an echo of Aham Brahmasmi (I am the infinite reality) of the Upanishads. There are striking similarities between the Hindu Advaita and Muslim Wahdat al-Wajud. These ideologies complement each other and lose their essence in isolation.

Punjab has been a centre of The Bhakti Movement – one of the most humanist spiritual movements that ever happened on this side of Suez – but all the humanist teachings of the movement could not avert the genocide of millions of Punjabis during the tragic events of the Partition.

The most time-tested peace ideology of Buddhism could not keep the Buddhists from killing Muslims in Burma.

Such are the cruel realities of modern times that can overshadow the viability of any spiritual movement.

Sufism in Sindh exists today as a way of life and not an ideology.

It is an inseparable part of how people live their daily lives. In Pakistan, however, to live a daily life has come to be an act of resistance itself.

Sindh bleeds today and mourns for its people and culture that are under attack. Bhit Shah reverberates with an aggrieved but helpless voice:

O brother dyer! Dye my clothes black,

I mourn for those who never did return.

(Sur Kedaro, III, Shah Jo Risalo)

Sindh is under attack. The land of Shah Latif bleeds again. The seven queens of Shah Latif’s Shah Jo Risalo – Marui, Sassui, Noori, Sorath, Lilan, Sohni, and Momal – have put on black cloaks and they mourn. The troubles and tribulations are not new for the queens.

After the sack of Delhi, Nadir Shah (Shah of Iran), invaded Sindh and imprisoned the then Sindhi ruler Noor Mohammad Kalhoro in Umarkot fort. Shah Latif captured it in the yearning of Marui for her beloved land when she was locked up in the same Umarkot fort.

If looking to my native land

with longing I expire;

My body carry home, that I

may rest in desert-stand;

My bones if Malir reach, at end,

though dead, I'll live again.

(Sur Marui, XXVIII, Shah Jo Risalo)

The attack on the central Imambargah in Shikarpur is as ominous in many ways as it is horrendous and tragic.

The Sufi ethos of Sindh has long been cherished as the panacea for burgeoning extremism in Pakistan. Sufism has been projected lately as an effective alternative to rising fundamentalism in Muslim societies not only by the Pakistani liberal intelligentsia but also by some Western think-tanks and NGOs.

But the question is, how effective as an ideology can Sufism be in its role in contemporary societies?

To begin with, Sufism is not a monolithic ideology.

There are several strains within Sufism that are in total opposition to each other, thus culminating into totally opposite worldviews. The most important of them is chasm between Wahdat al-Wajud (unity of existence) and Wahdat al-Shahud (unity of phenomenon).

The former professes that there is only One real being not separated from His creation, and thus God runs through everything. While Wahdat al-Shahud holds that God is separated from His creation.

While the distinction between the two might seem purely polemical, it actually leads to two entirely opposite logical conclusions.

Wahdat al-Wajud sees God running through everything. Thus apparent differences between different religions and school of thoughts vanish at once. In diversity, there lies a unity thus paving way to acceptance of any creed, irrespective of its religious foundations.

Ibn al-Arbi was the first to lay the theoretical foundations of Wahdat al-Wajud and introduce it to the Muslim world.

On the other hand, the Wahdat al-Shahud school of thought was developed and propagated by Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, who rose to counter the secular excesses of Akbar. He pronounced Ibn al-Arbi as Kafir and went on deconstructing what he deemed as heresies.

Wahdat al-Shahud in its sociopolitical context leads to separation and confrontation. The staunch anti-Hindu and anti-Shia views of Ahmed Sirhindi are just a logical consequence of this school of thought. Ahmed Sirhindi is one of the few Sufis mentioned in Pakistani textbooks.

Historically, Sufis in today’s Pakistan have belonged to four Sufi orders: Qadriah, Chishtiah, Suharwardiah, and Naqshbandiah.

It is also interesting to note that not all of these Sufi orders have been historically anti-establishment.

While Sufis who belonged to the Chishtiah and Qadriah orders always kept a distance from emperors in Delhi and kept voicing for the people, the Suharwardia order has always been close to the power centres. Bahauddin Zikria of the Suharwardiah order enjoyed close relations with the Darbar and after that leaders of this order have always sided with the ruler (either Mughals or British) against the will of the people.

Sufism in the subcontinent in general and Sindh in particular, emerged and evolved as a formidable opposition to the King and Mullah/Pundit nexus. Not only did it give voice to the voiceless victims of religious fanaticism, but also challenged the established political order.

To quote Marx it was ‘the soul of soulless conditions’.

A case-in-point is Shah Inayat of Jhok Sharif, who led a popular peasant revolt in Sindh and was executed afterwards. Shah Latif wrote a nameless eulogy of Shah Inayat in Shah Jo Risalo.

However, the socio-political conditions that gave rise to Sufism in the subcontinent are not present anymore. The resurrection of Sufism as a potent resistance ideology is difficult if not impossible. Sufis emerged from ashes of civilizational mysticism, independent of organised religion and political powers.

Today, however, the so-called centres of Sufism known as Khanqahs are an integral part of both the contemporary political elite and the all-powerful clergy. On intellectual front self-proclaimed proponents of contemporary Sufism – Qudratullah Shahab, Ashfaq Ahmad, Mumtaz Mufti, et al – have been a part of state apparatus and ideology in one form or another.

Sufism is necessarily a humanist and universal ideology. It is next to impossible to confine it to the boundaries of modern nation states and ideological states in particular, which thrive on an exclusivist ideology.

Mansoor al-Hallaj travelled extensively throughout Sindh. His famous proclamation Ana ‘al Haq (I am the truth) is an echo of Aham Brahmasmi (I am the infinite reality) of the Upanishads. There are striking similarities between the Hindu Advaita and Muslim Wahdat al-Wajud. These ideologies complement each other and lose their essence in isolation.

Punjab has been a centre of The Bhakti Movement – one of the most humanist spiritual movements that ever happened on this side of Suez – but all the humanist teachings of the movement could not avert the genocide of millions of Punjabis during the tragic events of the Partition.

The most time-tested peace ideology of Buddhism could not keep the Buddhists from killing Muslims in Burma.

Such are the cruel realities of modern times that can overshadow the viability of any spiritual movement.

Sufism in Sindh exists today as a way of life and not an ideology.

It is an inseparable part of how people live their daily lives. In Pakistan, however, to live a daily life has come to be an act of resistance itself.

Sindh bleeds today and mourns for its people and culture that are under attack. Bhit Shah reverberates with an aggrieved but helpless voice:

O brother dyer! Dye my clothes black,

I mourn for those who never did return.

(Sur Kedaro, III, Shah Jo Risalo)

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

Like al-Qaeda, the Islamic State spawned by those countries now in the lead to combat it.

Brahma Chellaney in The Hindu

Like al-Qaeda, the Islamic State has been inadvertently spawned by the policies of those now in the lead to combat it. But will anything substantive be learned from this experience?

U.S. President Barack Obama has labelled the jihadist juggernaut that calls itself the Islamic State a “cancer,” while his Defence Secretary, Chuck Hagel, has called it more dangerous than al-Qaeda ever was, claiming that its threat is “beyond anything we’ve seen.” No monster has ever been born on its own. So the question is: which forces helped create this new Frankenstein?

The Islamic State is a brutal, medieval organisation whose members take pride in carrying out beheadings and flaunting the severed heads of their victims as trophies. This cannot obscure an underlying reality: the Islamic State represents a Sunni Islamist insurrection against non-Sunni rulers in disintegrating Syria and Iraq.

Indeed, the ongoing fragmentation of states along primordial lines in the arc between Israel and India is spawning de facto new entities or blocks, including Shiastan, Wahhabistan, Kurdistan, ISstan and Talibanstan. Other than Iran, Egypt and Turkey, most of the important nations from the Maghreb to Pakistan (an internally torn state that could shrink to Punjabistan or, simply, ISIstan) are modern western concoctions, with no roots in history or pre-existing identity.

The West and agendas

It is beyond dispute that the Islamic State militia — formerly the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant — emerged from the Syrian civil war, which began indigenously as a localised revolt against state brutality under Syrian President Bashar al-Assad before being fuelled with externally supplied funds and weapons. From Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)-training centres in Turkey and Jordan, the rebels set up a Free Syrian Army (FSA), launching attacks on government forces, as a U.S.-backed information war demonised Mr. Assad and encouraged military officers and soldiers to switch sides.

It is beyond dispute that the Islamic State militia — formerly the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant — emerged from the Syrian civil war, which began indigenously as a localised revolt against state brutality under Syrian President Bashar al-Assad before being fuelled with externally supplied funds and weapons. From Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)-training centres in Turkey and Jordan, the rebels set up a Free Syrian Army (FSA), launching attacks on government forces, as a U.S.-backed information war demonised Mr. Assad and encouraged military officers and soldiers to switch sides.

“By seeking to topple a secular autocracy in Syria while simultaneously working to shield jihad-bankrolling monarchies from the Arab Spring, Barack Obama ended up strengthening Islamist forces.”

“By seeking to topple a secular autocracy in Syria while simultaneously working to shield jihad-bankrolling monarchies from the Arab Spring, Barack Obama ended up strengthening Islamist forces.”

But the members of the U.S.-led coalition were never on the same page because some allies had dual agendas. While the three spearheads of the anti-Assad crusade — the U.S., Britain and France — focussed on aiding the FSA, the radical Islamist sheikhdoms such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates as well as the Islamist-leaning government in Turkey channelled their weapons and funds to more overtly Islamist groups. This splintered the Syrian opposition, marginalising the FSA and paving the way for the Islamic State’s rise.

The anti-Assad coalition indeed started off on the wrong foot by trying to speciously distinguish between “moderate” and “radical” jihadists. The line separating the two is just too blurred. Indeed, the term “moderatejihadists” is an oxymoron: Those waging jihad by the gun can never be moderate.

Invoking jihad

The U.S. and its allies made a more fundamental mistake by infusing the spirit of jihad in their campaign against Mr. Assad so as to help trigger a popular uprising in Syria. The decision to instil the spirit of jihad through television and radio broadcasts beamed to Syrians was deliberate — to provoke Syria’s majority Sunni population to rise against their secular government.

The U.S. and its allies made a more fundamental mistake by infusing the spirit of jihad in their campaign against Mr. Assad so as to help trigger a popular uprising in Syria. The decision to instil the spirit of jihad through television and radio broadcasts beamed to Syrians was deliberate — to provoke Syria’s majority Sunni population to rise against their secular government.

This ignored the lesson from Afghanistan (where the CIA in the 1980s ran, via Pakistan, the largest covert operation in its history) — that inciting jihad and arming “holy warriors” creates a deadly cocktail, with far-reaching and long-lasting impacts on international security. The Reagan administration openly used Islam as an ideological tool to spur armed resistance to Soviet forces in Afghanistan.

In 1985, at a White House ceremony in honour of several Afghan mujahideen — the jihadists out of which al-Qaeda evolved — President Ronald Reagan declared, “These gentlemen are the moral equivalent of America’s Founding Fathers.” Earlier in 1982, Reagan dedicated the space shuttle ‘Columbia’ to the Afghan resistance. He declared, “Just as the Columbia, we think, represents man’s finest aspirations in the field of science and technology, so too does the struggle of the Afghan people represent man’s highest aspirations for freedom. I am dedicating, on behalf of the American people, the March 22 launch of the Columbia to the people of Afghanistan.”

The Afghan war veterans came to haunt the security of many countries. Less known is the fact that the Islamic State’s self-declared caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi — like Libyan militia leader Abdelhakim Belhadj (whom the CIA abducted and subjected to “extraordinary rendition”) and Chechen terrorist leader Airat Vakhitov — become radicalised while under U.S. detention. As torture chambers, U.S. detention centres have served as pressure cookers for extremism.

Mr. Obama’s Syria strategy took a page out of Reagan’s Afghan playbook. Not surprisingly, his strategy backfired. It took just two years for Syria to descend into a Somalia-style failed state under the weight of the international jihad against Mr. Assad. This helped the Islamic State not only to rise but also to use its control over northeastern Syria to stage a surprise blitzkrieg deep into Iraq this summer.

Had the U.S. and its allies refrained from arming jihadists to topple Mr. Assad, would the Islamic State have emerged as a lethal, marauding force? And would large swaths of upstream territory along the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers in Syria and Iraq have fallen into this monster’s control? The exigencies of the topple-Assad campaign also prompted the Obama administration to turn a blind eye to the flow of Gulf and Turkish aid to the Islamic State.

In fact, the Obama team, until recently, viewed the Islamic State as a “good” terrorist organisation in Syria but a “bad” one in Iraq, especially when it threatened to overrun the Kurdish regional capital, Erbil. In January, Mr. Obama famously dismissed the Islamic State as a local “JV team” trying to imitate al-Qaeda but without the capacity to be a threat to America. It was only after the public outrage in the U.S. over the video-recorded execution of American journalist James Foley and the flight of Iraqi Christians and Yazidis that the White House re-evaluated the threat posed by the Islamic State.

Full circle

Many had cautioned against the topple-Assad campaign, fearing that extremist forces would gain control in the vacuum. Those still wedded to overthrowing Mr. Assad’s rule, however, contend that Mr. Obama’s failure to provide greater aid, including surface-to-air missiles, to the Syrian rebels created a vacuum that produced the Islamic State. In truth, more CIA arms to the increasingly ineffectual FSA would have meant a stronger and more deadly Islamic State.

Many had cautioned against the topple-Assad campaign, fearing that extremist forces would gain control in the vacuum. Those still wedded to overthrowing Mr. Assad’s rule, however, contend that Mr. Obama’s failure to provide greater aid, including surface-to-air missiles, to the Syrian rebels created a vacuum that produced the Islamic State. In truth, more CIA arms to the increasingly ineffectual FSA would have meant a stronger and more deadly Islamic State.

As part of his strategic calculus to oust Mr. Assad, Mr. Obama failed to capitalise on the Arab Spring, which was then in full bloom. By seeking to topple a secular autocracy in Syria while simultaneously working to shield jihad-bankrolling monarchies from the Arab Spring, he ended up strengthening Islamist forces — a development reinforced by the U.S.-led overthrow of another secular Arab dictator, Muammar Qadhafi, which has turned Libya into another failed state and created a lawless jihadist citadel at Europe’s southern doorstep.

In fact, no sooner had Qadhafi been killed than Libya’s new rulers established a theocracy, with no opposition from the western powers that brought about the regime change. Indeed, the cloak of Islam helps to protect the credibility of leaders who might otherwise be seen as foreign puppets. For the same reason, the U.S. has condoned the Arab monarchs for their long-standing alliance with Islamists. It has failed to stop these cloistered royals from continuing to fund Muslim extremist groups and madrasas in other countries. The American interest in maintaining pliant regimes in oil-rich countries has trumped all other considerations.

Today, Mr. Obama’s Syria policy is coming full circle. Having portrayed Mr. Assad as a bloodthirsty monster, Washington must now accept Mr. Assad as the lesser of the two evils and work with him to defeat the larger threat of the Islamic State.

The fact that the Islamic State’s heartland remains in northern Syria means that it cannot be stopped unless the U.S. extends air strikes into Syria. As the U.S. mulls that option — for which it would need at least tacit permission from Syria, which still maintains good air defences — it is fearful of being pulled into the middle of the horrendous civil war there. It is thus discreetly urging Mr. Assad to prioritise defeating the Islamic State.

Make no mistake: like al-Qaeda, the Islamic State is a monster inadvertently spawned by the policies of those now in the lead to combat it. The question is whether anything substantive will be learned from this experience, unlike the forgotten lessons of America’s anti-Soviet struggle in Afghanistan.

At a time when jihadist groups are gaining ground from Mali to Malaysia, Mr. Obama’s current effort to strike a Faustian bargain with the Afghan Taliban, for example, gives little hope that any lesson will be learned. U.S.-led policies toward the Islamic world have prevented a clash between civilisations by fostering a clash within a civilisation, but at serious cost to regional and international security.

Saturday, 14 June 2014

Welcome to Pseudo-Democracy – Unpacking the BJP Victory: Irfan Ahmad

MAY 25, 2014

tags: BJP victory 2014, Narendra Modi, RSS

by Nivedita Menon in Kafila

Guest Post by IRFAN AHMAD

This article offers a preliminary analysis of what the Modi phenomenon means in terms of BJP’s sweeping win on 16 May. It makes four propositions.

First, we stop seeing it as an individual phenomenon centered on the personality of Modi even as his votaries as well as some critics tend to view it that way.

Second, the Modi phenomenon is triumph of a massive ideological movement at the center of which stands the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, RSS. Sharply distinguishing between the BJP and the RSS is a naivety; the RSS’ influence goes far beyond as numerous politicians under its influence have gone to the non-RSS parties in the same way as politicians from the non-RSS parties have joined the RSS-BJP collective.

Third, the BJP victory is neither due to development nor due to anti-corruption but due to Hindutva dressed as development so that both were rendered synonymous. The BJP victory, I contend, is an outcome of a violent mobilization against “the other”, Muslims.

Fourth, BJP’s victory is not the triumph of democracy but its subversion. Charting a different genealogy of demokratiain Greek, I argue how it is pseudo democracy.

As I explain these propositions, I request readers to be somewhat patient –they are a bit long, like the night of 16 May.

Charisma: Assembled, Loaded and Televised

In a live interview to a Singapore-based television channel on the final day of voting, I was asked what I thought of Modi as a “very charismatic person” and his track record of economic growth and delivery. Clearly, Modi’s charisma was no longer merely national; it was internationalized much like the profiteering McDonald as a brand. Such a ubiquity of wave or charisma of Modi entails understanding charisma afresh. For sociologist Max Weber, charisma means the belief among followers in a leader that he has an extraordinary quality as a gift from the grace of God. But how do followers think of someone as a leader in the first place? And how do they subsequently believe that the leader has charisma?

There is no inherent charisma; certainly, not in the 2014 elections. It was built brick by brick by turning corporate theft, ecological degradation and the state-supervised pogrom into development, silenced dissent into celebrated consensus, large crimes into even larger rallies of pride (recall gauraw yātrās). The charismatic leader saw corruption and showed corruption to people only in his rival parties but never told people about Bangaru Laxmans or B.S. Yedurappas and several others within the party whose corruption doesn’t even become a public issue. That is, charisma emanated from showing corruption outside while hiding it within. Yes, it required charisma to dub those speaking out against the state violence of 2002 as promoting divisiveness over development. These “conservatives” clung to the past while the charismatic leader wished to “move ahead” on the highway of future “development” he had already delivered.

In short, the transformation of political ugliness into a bumper sale of development with charismatic Modi at the center required much labor, creativity, coordination, manpower, involvement of internationally-trained professionals, production of comic books to inspire children through Modi’s personal life story and a gigantic sum of money. In one estimate Rs. 5,000 crore (over US $900 million Dollars) was spent on advertisement alone (EPW, 24 May, p.7) –at the rate of Rs. 20 per lunch, the entire population of India, 125 crore, would have enjoyed lunch for full two days. But still all these wouldn’t have mattered significantly if they were not televised by media which obediently did. It won’t be unreasonable to say, then, that Modi’s charisma is a gift from the grace of mammon, television, Google, social media and YouTube.

The Omnipresent Collective behind the Individual

If charisma is not an inherent quality dwelling within the individual – charisma of Vinoba Bhave the “saint” who engineered the Bhoodan movement and is considered one of the most charismatic leaders in independent India was enmeshed in an economic matrix and crafted by the massive political machinery and leaders of that time, Jawaharlal Nehru included (TK Oommen “Charisma, Social Structure and Change”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1967) –what is the political collective that explains Modi’s charisma? The answer is short: the RSS which has the explicit goal of making India into a Hindu state with Muslims as its prime foe. What was distinct about the 2014 elections was that RSS’ myriad organizations –in all age groups, across gender, every walk of life and every corner of India –swung into action on camera. Unlike in the past, the RSS and the BJP publicly and proudly acknowledged their mutual contributions. The mask that the RSS was just a cultural, not political, organization was cast off. So, the question if the BJP government would be remote-controlled by the RSS headquarters in Nagpur is redundant. A day after the victory, Uma Bharti, a senior BJP leader, told NDTV:

There shouldn’t be any hesitation (sankōch) in accepting that the RSS is our policy director (nītī nirdēshak). What they [the RSS] have taught us has got mixed in our blood. Therefore, they don’t even need to remind us [the BJP].There is no need for remote control [of the BJP by the RSS]. We have come under self-control through them. We too have begun to think the way they think. Therefore, there is no need for a remote control. Now the countrymen have put a stamp of approval on it [the RSS]. A swayamsewak of the RSS who has also been itsparchārak is set to become Prime Minister of the country… People themselves have accepted our ideology.

There is no further need to belabor this point for the Kafila readers. What needs to be stressed is that the influence of Hindutva is not limited to the RSS family for it goes far beyond and deeper. That the ideology of Hindutva –different from Hinduism as a religious tradition(s) prior to the Nineteenth century –is also shared by individuals in explicitly non-Hindutva parties and organizations has a longer history. KM Munshi (1887–1971) joined the Indian National Congress in 1929 and described himself as a Gandhian. While in the Congress, he had developed such close relations with the Hindu Mahasabha (HM) that many, including Bhai Premchand, ex-President of the HM, held that Munshi’s “ideas were just the same as that of the Hindu Mahasabha”. Munshi had also joined the akhāṛās, gymnasia, for “training our [Hindu] race in the art of self-defense”. Given his militancy, he was advised to leave the Congress. Later he established Akhand Hindustan Conference to become its President. That Munshi was a Hindu nationalist determined to reestablish the Hindu glory, calling Muslims “goondas”, foreigners, invaders and Islam constituting a dark chapter in India’s history, was manifest in his numerous writings. Well-known was also his friendship with the Hindutva ideologues: VD Savarkar, BS Moonje, and Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Yet, in 1946, M.K. Gandhi asked Munshi to rejoin the Congress (Manu Bhagavan, “The Hindutva Underground”, Economic & Political Weekly, 2008).

Before I come to the post-colonial period, let me mention three other examples. Lala Lajpat Rai (1865–1928) resigned from the Congress to become the President of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1925. On Jawaharlal Nehru’s invitation Shyama Prasad Mookerjee (1901–1953), ex-President of the Hindu Mahasabha and founder of the Jana Sangh, predecessor of the BJP, joined the Cabinet Nehru formed after Partition. Pundit Madanmohan Malaviya (1861–1946), twice presidents of the Congress in 1909 and 1918, became the President of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1923 (Christophe Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalism Reader, 2006, pp.61–62). With Malaviya’s help, the RSS started its shākẖasat the Banaras Hindu University (Pralay Kanungo, RSS’S Tryst With Politics, 2002, p. 49).

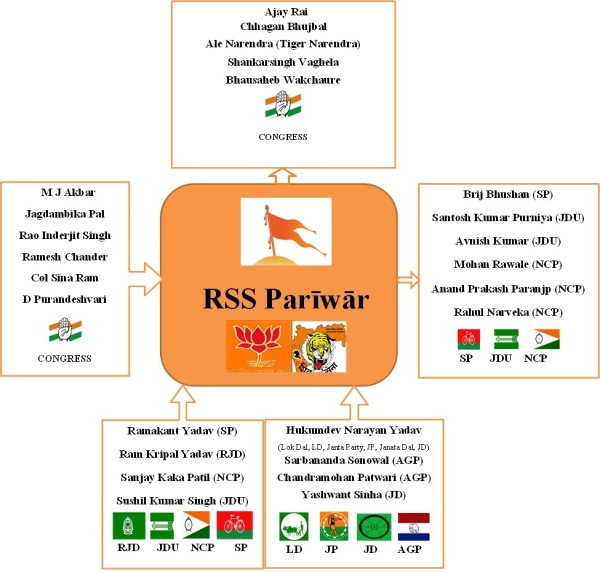

The crisscross between the RSS ideology/family and the non-RSS formations continued after 1947 as the table, by no means complete and based on individuals only (of more recent past) , shows below.

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947

The flow between the RSS ideological camp and the non-RSS parties is epic, not episodic, enduring, not fleeting. It grows out of a sustained ideological groundwork to secure political equivalence. As the table above shows, Ajay Rai switched from the BJP to Samajwadi Party and then to the Congress to contest against Modi in Varanasi. Rarely did Rai ever critique the BJP or Modi. His sole claim against Modi and Arvind Kejriwal was that while his rivals were outsiders to Varanasi he alone was a local (asthānīye) candidate. In a special session of the Gujarat Assembly bidding farewell to Modi, on 21 May, Shankar Sinh Vaghela, Congress Leader of the Opposition not only praised Modi but asked him to build the Ram Temple at Ayodhya (obviously the Babri masjid is not even an issue). He also backed Modi and the BJP on other contentious issues. Friedrich Engels’ (d. 1895) remark that “the names of political parties are never entirely right” has some merit.

My point about the political equivalence is not an external attribution but the self-claim by the RSS which should be duly acknowledged as it is. When asked about the RSS appeal across political parties, Ram Madhav, the RSS spokesperson said in 2009:

We have our members in several political parties, including the Congress. We interact with them regularly…The BJP is closest to us in…ideology. Someone is 10 feet away from us; someone else is 1 km away, that’s the difference.

Responding to a similar question, Mohan Bhagwat, the new RSS Sarsanghchālak, head, offered more details:

Joining parties other than BJP depends on the individual thinking of a swayamsewak. And swayamsewaks are present in many parties. This I can tell you. Have you heard of Tiger Narendra in Andhra [Pradesh]? … Earlier he was in the BJP, now he is not [later Narendra became an MP from the Congress in 1999 and from Telangana Rashtra Samithi in 2004]… I had gone to Varanasi where the President of the city’s weyāpāri mandal was from the Samajwadi Party as well as the gẖatnāyak [group leader] of our shākẖa there. In the camp (mahāshīwir) of Agra many district-level workers of the BSP took part… We don’t count who is from which party or caste…We consider them all Hindus.

Hindutva as Development

It is against this wider backdrop of the organizational infrastructure and ideological apparatus that the claim by the BJP and the media that the latter won on the plank of development should be unpacked. To begin with, there is no single party which is opposed to development; every party vouches for development. So how did development and the BJP become synonymous? Consider Bihar under Nitish Kumar in alliance with the BJP. As long as this alliance was in place, Bihar was projected as a model of development next only to Gujarat. However, as the alliance broke in June 2013, we were told, Bihar’s development not only stopped but also declined. In March 2014, The Times of Indiareported that its GDP dramatically declined from 15.05% during 2012–13 to an estimated 8.82% during 2013–2014. While I am not an economist, this conclusion would be convincing if it also showed a major shift in the policy in less than a year and causally linked it to the decline. So, the message of The Times of India was plain: the BJP alone could guarantee development because after the breakup of alliance, development of Bihar drastically declined. The report was not about political economy. It was more about politics and less about economy.

When the alliance between Nitish Kumar and the BJP was intact, Bihar was also regarded as a well-administered state in terms of law and order, “good governance”, again only next to Gujarat. Soon after the dissolution of the alliance Bihar returned to jungle raj. Giriraj Singh, a key Bihar BJP leader, said: “Since the breakup of alliance [between Nitish Kumar and the BJP] there is nothing called government…law and order [in Bihar]”.

The logic of development as a winning catalyst is flawed because in the states of Bihar and UP –from where the BJP won over 100 seats –the RSS-BJP had systematically manufactured an anti-Muslim polarization to consolidate the “Hindu Vote”. In UP it began with the Muzaffarnagar riots operationalized through an incident in Kaval village in August 2013 as a result of which over 50,000 Muslims were rendered as refugees living in various camps. In early January 2014, with some journalists-academics I visited many camps, including the village Kakra and the police station nearby. There was a perfect harmony in the accounts of villagers, police officials and Kakra chief (pradẖān). They all held that Muslims themselves burnt their houses and willingly left villages to claim compensation from the state government. They were “greedy”. So massive was this propaganda that the simple fact that the promised amount of compensation was far lower than the price of their lost land and properties didn’t matter. The police told us that they made every effort to arrest the culprits responsible for loot and arson but they could not find them. While in Kakra, we found the culpritsliving there without any fear; one of them saying that the police lacked courage to touch them. The Muzaffarnagar riots were preface to the 2014 elections which the BJP won.

Two months later, in October 2013, in Bihar too the anti-Muslim campaign began with the explosions in the Patna rally to be addressed by Modi. Soon after the blast, TV channels such as News 24 showed one Pankaj as culprit and police arresting him. Firstpost reported that Ramnarayan Singh, Vikas Singh and Munna Singh were suspects. Within hours, as Beyondheadlines noted, the narrative changed as did the names of the suspect. Suspects became Muslims and their names began to circulate on television screens. The National Investigation Agency arrested Aftab Alam from Muzaffarpur where my parents live. Though released after a few days, media was awash with equation between Islam and terrorism and both against India. The colony where Alam lived was described as “mini Pakistan” by local Hindi media as well as many people in the “civil society”. So terrorized were Muslims in Muzaffarpur that they stopped greeting Alam after his release. When I expressed my desire to meet Alam, many of my relatives advised me not to. I did meet him.

From the time of the Patna blast the political field was methodically mobilized along the religious lines as a result of which electorally Bihar was as productive to the BJP as was the UP after the Muzaffarnagar riots. It was precisely because of such a line of political enmity sharply drawn well before the elections with a specific electoral purpose that at their conclusion Modi said: “There is no enmity in democracy but there is competition”. Does not this appear like an affirmation through the crooked lane of denial?

Let me conclude this section on development with the statement of Uma Bharti. When asked if Modi would give priority to Hindutva over development, she said:

“Hindutva is breath of life (prān) of India… However, prān remains still in its place… Things which require maintenance are hands, feet and eyes –in other words, development”.

Faces of Pseudo Democracy: Terror of Mercy

A day before counting began Chetan Bhagat wrote a blog for The Times of India. Predicting that the BJP with “near boycott by the Muslim community” will win an “all-time high Hindu power”, he posed questions and answered them as follows:

What do the BJP and Indian majority do with this new Hindu power? Do we use it to settle scores with Muslims? Do we use it to establish a majoritarian, intolerant state where minorities are ‘put in their place’? Do we impose ourselves and say things like, ‘India is the land of Hindus’? Do we make laws more in line with Hindu religion?Frankly, we may have the power to do some of these things now. It may even appeal to sections of the population. However, be warned. This would be an awful and terrible use of this power. In the long term, such a thought process will only turn us into a conservative, regressive, unsafe and poor country where nobody would want to come for business (emphasis added).

While Bhagat’s questions are clear, his answers are not. Of the items listed in questions, in his answer he refers to “some of these things” leaving it for the readers “which ones”. What is clear, however, is that in warning about the terrible use of power, he brazenly violates the innate worth and dignity of humans and shows concern for them because “nobody would want to come for business”. Such a beastly urge –even beasts don’t have that –where treatment of humans (Muslims) is predicated on the calculations of profit and capital, is not a value for most followers of any religion, including Hinduism, in whose name Bhagat speaks. Bhagat’s vocabulary draws less from religion and more from its entanglement with supremacist nationalism and majoritarian democracy both of which must have been strangers to our forefathers in Vedic times. His invocation of the “Indian majority” which he equates with Hindus is a common, though flawed, understanding of democracy. Many dissenting with Bhagat’s lines of thinking, however, accept the idea of a Hindu majority but reject the BJP’s claim to represent all Hindus by arguing that two-thirds of them did not vote for it. Statistically, it is correct. Philosophically, it is not for it concedes the idea of an ethno majority as central to democracy.

Against the received wisdom political theorist Josiah Ober recently argued that the original meaning of demokratia in Greek is “capacity to do things, not majority rule”. In contrast to monarchia (monos: one) and oligarchia (hoi oligoi: the few), demokratia has no reference to number. It connotes a collective body of people. Since nowhere is any people monolithic, the capacity to do things would be diverse and multiple as would be the cultural goals and political idioms. The equation between democracy and majority rule was pejoratively done by Greek critics of democracy. Is it not strange that contemporary votaries of majority rule like Bhagat share grounds with ancient opponents of democracy? It is precisely this equivalence between democracy and the rule by majority where majority is construed as a distinct ethno that has caused massive violence across the globe. Theodore Roosevelt’s statement that “Extermination [of Indians] was ultimately as beneficial as it was inevitable” bears testimony to such a bloody notion of democracy.

Shortly before the build-up to the 2014 elections, Uma Bharti told Aaj Tak that “Only right-wing Hindutva leaders can be the savior of Muslims and guarantee their security. Only we can instill confidence and erode fear from the Muslim psyche”. On close reflections, it is not difficult to see that this grand assurance conceals a grander danger and threat. Like terror and mercy security and the very threat to that security are intimately connected; they are the cover and back page of the same book. To invoke Slavoj Žižek, “only a power which asserts its full terrorist…capacity to destroy anything and anyone it wants” can speak of “infinite mercy” by guaranteeing security to Muslims. Does a vocal democracy rob people of their capacity to do things and destine them to be no more than silent objects of securitization?