Shehab Khan in The Independent

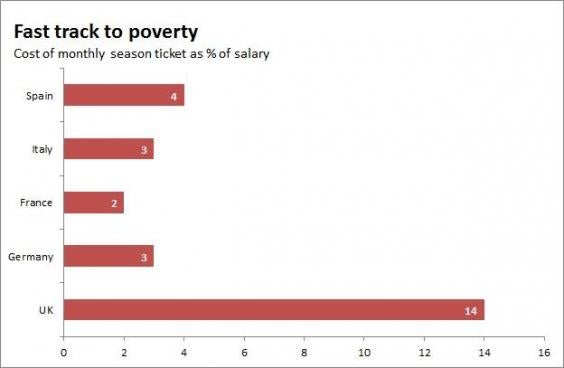

Rail passengers are spending six times more on fares than their peers in Europe - with 14 per cent of their income being spent on monthly season tickets.

Those commuting from Luton to London pay an average of £387 a month, significantly more than the £61 paid by those in Paris and Rome.

This equates to an average of 14 per cent of monthly earnings, significantly higher than the 2 per cent seen in France, 3 per cent in Germany and 4 per cent in Spain, according to Action for Rail.

TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady said that not only are prices high but trains were “overcrowded”, “understaffed” and the infrastructure was “out-of-date”.

"British commuters are forced to shell out far more on rail fares than others in Europe. Many will look with envy at the cheaper, publicly-owned services on the continent,” he said.

"Years of failed privatisation have left us with sky-high ticket prices, overcrowded trains, understaffed services and out-of-date infrastructure. Private train companies are milking the system, and the government is letting them get away with it."

Country

|

From

|

To

|

Distance (miles)

|

Monthly season ticket cost

|

Monthly earnings

|

% of monthly earnings

|

UK

|

Luton

|

London St. Pancras

|

35

|

£387

|

£2,759

|

14%

|

UK

|

Liverpool Lime Street

|

Manchester Piccadilly

|

32

|

£292

|

£2,759

|

11%

|

Germany

|

Dusseldorf

|

Cologne

|

28

|

£85

|

£2,624

|

3%

|

France

|

Mantes-la-Jolie

|

Paris

|

34

|

£61

|

£2,545

|

2%

|

Italy

|

Anzio

|

Rome

|

31

|

£61

|

£2,015

|

3%

|

Spain

|

Aranjuez

|

Madrid

|

31

|

£75

|

£1,917

|

4%

|

RMT General Secretary Mick Cash said: "British passengers are paying the highest fares in Europe to travel on rammed services while the private train companies are laughing all the way to the bank. Companies like Southern Rail and their French owners are siphoning off cash to subsidise rail services in Paris and beyond."

Mick Whelan, the General Secretary of ASLEF added: "It is scandalous that the government is allowing privatised train companies to make even more money for providing an ever-poorer service. We have the most expensive railway in Europe and the train companies, aided and abetted by this government, are about to make it even more costly for people to travel."

Transport Secretary, Chris Grayling said: “Thanks to action by the Government on train ticket prices, wages are growing faster than regulated fares. This commitment to cap regulated fares in line with inflation will save annual season ticket holders an average £425 in the five years to 2020.

“To improve services, we are investing more than £40billion into our railways. This will provide passengers with better trains that are faster and more comfortable.

"We are delivering the biggest rail modernisation programme for more than a century, providing more seats and services. We have always fairly balanced the cost of this investment between the taxpayer and the passenger.

"On average, 97% of every £1 of a passenger's fare goes back into the railway.”