Batting is about death. And life of course. It's all about how useful - how good - a life you lead before you die. You are surrounded by pitfalls and bayed about by enemies, but the good person will come through adversity to triumph. And the less good person won't.

That life-and-death metaphor gives cricket its USP: its own particular force and vividness. Cricket - red-ball cricket in particular - is all about the little death of dismissal. Every great innings takes place in the shadow of fallibility. That, in the end, is what cricket means.

Batsmen, writes Simon Hughes, "are walking the tightrope between success and failure. One minuscule error and they're toast. Terminé. Caput."

Hughes has always brought an original mind to the interpretation of cricket. He invented the concept of The Analyst for Channel Four in Britain, and now he tries to analyse batsmanship in his latest, highly enjoyable book, Who Wants to be a Batsman? He calls on his experience of more than 200 first-class innings, and his career-long struggle to add a decent batting CV to the deceptively fast arm he possessed as a bowler.

He returns to the infinitely fragile nature of every batsman's experience. "In tennis, if you lose 6-0 6-0 and haven't returned a single ball, you will have still served a few yourself. You have contributed something to the match. In football, unless you score an own goal with the last kick of the game, you have got time to atone for any mistake you might have made. Hell, even if you have shanked every drive into the bushes on the golf course, there is always hope that you will nail one down the middle on the eighteenth…

"But nought in cricket. What has that achieved?"

Cricketers cherish the notion that a bowler can bowl a bad ball that's whacked for six and get a wicket next ball, but one error - one tiny, measly error - from the batsman and he's gone.

A batsman needs to combine rampant egomania with the selflessness of a Zen monk, and to hold the two things in perfect balance

But it's not necessarily true. And even if it were, it wouldn't be unique in sport. Batsmen make mistakes and survive. Very few batsmen reach three figures without a play-and-miss or a false shot. Perhaps every century is a demonstration of how much the batsman has got away with.

Joe Root made a major error in the first Test of the recent Ashes series. He should have been out for nought and gone back to the pavilion asking himself what he had achieved. But Brad Haddin dropped the chance, Root made a century, England won and Root was the hero.

In other words, and contrary to standard wisdom, there is a margin for error in batting. The top players are better at coping with it, and above all, better at cashing in when matters beyond their control happen to work in their favour.

The routine humiliation of dismissal is not unique to cricket. There are quite a few sports in which your participation can be over before the finish - and long before you're ready to give up. Sonny Liston failed to complete either of his two fights against Muhammad Ali: quitting on his stool in the first and knocked out in the second.

In all jumping competitions in the horsey world your participation can end prematurely with an involuntary dismount. I have watched the Grand National favourite fall at the first fence. I have experienced a public crash-landing or two myself, as it happens, and believe me, it hurts more than being clean bowled - about which, too, I know in more detail than I would wish.

In sports more dangerous than cricket every competitor knows that participation could end with the assistance of a stretcher. In some sports real deaths happen more often than they do in cricket. Let's have a moment of silence for Phillip Hughes at this point - but we should also recall that in 1999 five people were killed in the equestrian sport of eventing.

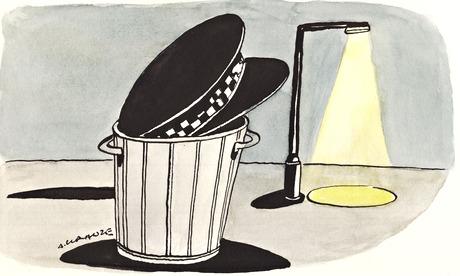

Back to the pavilion before facing a ball: Usain Bolt is disqualified in the final of the World Athletics Championships © AFP

In track and field, errors are savagely punished, and sometimes it's worse than getting out first ball. It's like being sent back to the pavvy for taking guard wrong. You're out without running a single stride of the race. Terminé. Caput. It happened to Usain Bolt in the final of the World Championships in 2011.

So I dispute the self-pitying notion of all batsmen (and ex-batsmen in the commentary box) who tell us that batting is a uniquely fragile sporting discipline. It just feels like that when you're out there.

That doesn't mean that a batsman is not in a unique position, and that it's not fraught with psychological problems of all kinds. It's just that cricketers - tied up in the intricacies of a single sport - tend not to identify the uniquely troubling aspect of batsmanship. It's the twin load of responsibility. When you fail as a batsman you have not one but two reasons to feel bad. You have lost a contest against another individual - and you have also let down your colleagues. You have failed yourself andyou have failed your team.

That's a hefty burden to bear. Of course there's an essence of that in all team sports - it's rather the point of them. But in most team sports you are operating with others. A goalkeeper in football is not as isolated as he looks: he's in constant dialogue with his central defenders, and his distribution of the ball is a core skill.

A batsman is as lonely as a golfer or a tennis player - but he's also working for other people. In some competitions they make tennis players and golfers shoulder a batsman's twin responsibilities: the Ryder Cup, Solheim Cup, Davis Cup and Fed Cup. Often you see great players unable to cope with a secondary responsibility: Tiger Woods never got the hang of it.

A great batsman must be like a top Ryder Cup golfer, not once every two years but in every single innings. He must - like Colin Montgomerie - find inspiration in this double responsibility. Woods goes straight back to strokeplay golf; for a batsman there is no other game.

If you fail as a batsman, you must deal with your personal inadequacies. Graham Gooch began his Test career with a pair. Repeated failure will cost you your place in the team. Your career will suffer. So will your sense of self-worth. But failure will also cost your team. You will fail to contribute. You will stop feeling like a part of the whole. You will lose matches and even if no one says anything, you know what you've done and what you haven't done.

Every great innings takes place in the shadow of fallibility. That, in the end, is what cricket means

It's the double whammy that's unique to batsmanship. That extends to cricket's bastard sister, baseball; the difference here is that baseball is weighted towards the pitcher and a dismissal is a relatively trivial matter; it's a run that's a big deal. All the same, the batter and the batsman share a double burden .

It follows, then, that again and again Simon Hughes goes back to the mental side of things. He offers "Ten Wanna Be Batsman Rules": of these, eight are mental. One is semi-facetious (this is "Yozzer" writing after all) and rule eight is "play at the Oval." The only physical tip is "Keep the head still."

It's almost as if every batsman had the same amount of physical ability, and that the only difference between good and great was mental posture. That's clearly not true: David Gower, Brian Lara and Kevin Pietersen clearly had something extra. But they also had mental ability: they could put errors behind them, didn't get sucked into the wrong sort of confrontation, knew how to pace an innings, understood when to stick and when to twist.

In cricket you often see a player of (comparatively) limited physical ability playing any number of match-winning innings because of a great mental attitude. Alastair Cook is a classic example of this type.

A player with a lesser degree of pure talent never takes success for granted. He is naturally disposed to make the most of every let-off. Thus you can turn an apparent disadvantage into an advantage. That's one of the most fascinating things about sport - and it's very cricket.

Batting is about shame and guilt: the shame of personal failure and the guilt at playing a part in team failure. It's also about escaping from - or being inspired by - these two things to find individual and corporate glory. You must sink yourself into the common cause without losing your sense of individuality.

A batsman needs to combine rampant egomania with the selflessness of a Zen monk, and to hold the two things in perfect balance. Unsurprising, then, that excellence is a rare thing - and that we value it so highly when we find it.