“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label culture. Show all posts

Showing posts with label culture. Show all posts

Saturday 21 January 2023

Monday 2 January 2023

Friday 4 November 2022

Monday 12 September 2022

Saturday 18 June 2022

Sunday 5 June 2022

THE PERFORMATIVE POLITICIAN

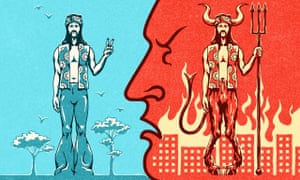

Nadeem F Paracha in The Dawn

Illustration by Abro

Illustration by AbroPopulism is a way of framing political ideas that can be filled with a verity of ideologies (C. Mudde in Current History, 2014). These ideologies can come from the left or the right. Populism in itself is not a distinct ideology. It is a performative political style.

No matter where it’s coming from, it is manifested through a particular set of animated gestures, images, tones and symbols (B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism, 2016). At the core of it is a narrative containing two main ‘villains’: The ‘elites’ and ‘the other’. Elites are described as being corrupt. And ‘the other’ is demonised as being a threat to the beliefs and values of the ‘majority’.

Populists begin by glorifying the ‘besieged’ polity as noble. They then begin to frame the polity’s civilisation as ‘sacred’. Therefore, the mission to eradicate threats, in this context, becomes a sacred cause. The far-right parties in Europe want to protect Europe’s Christian identity from Muslim intruders. They see Muslim immigration to European countries as an invasion.

Yet, these far-right groups are largely secular. They do not propose the creation of a Christian theocracy. Instead, they understand modern European civilisation as the outcome of its illustrious Christian past. They frame the Muslim immigrant as ‘the other’ who has arrived from a lesser civilisation. So, according to far-right populists in Europe, the Muslim other — tolerated and facilitated by a political elite — starts to undermine the Christian values that aided European civilisations to become ‘great’.

Ironically, most far-right outfits in Europe that espouse such notions are largely critical of conventional Christian institutions. They see them as being too conservative towards modern European values. Far-right outfits are not overtly religious at all — even though their fiery populist rhetoric frames their cause as a sacred undertaking to protect the civilisational role of Christianity in shaping European societies.

Thus, European far-right populists adopt Christianity not as a theocratic-political doctrine, but as an identity marker to differentiate themselves from Muslims (Saving The People, ed. O. Roy, 2016). It is therefore naive to understand issues such as Islamophobia as a tussle between Christianity and Islam. Neither is it a clash between modernity and anti-modernity, as such.

The actions of some Islamist extremists, and the manner in which these were framed by popular media, made Muslim migrants in the West a community that could be easily moulded into a feared ‘other’ by populists. If one takes out the Muslim migrants from the equation, the core narrative of far-right populists will lose its sting.

Muslims in this regard have become ‘the other’ in India as well. Hindu nationalism is challenging the old, ‘secular’ political elite by claiming that this elite was serving Muslim interests to maintain its political hegemony, and that it was repressing values, beliefs and memories of a Hindu civilisation that was thriving before being invaded and dismantled by Muslim invaders.

Here too, the populist Hindu nationalists are not necessarily devout and pious. And when they are, then the actions in this respect are largely performative rather than doctrinal. That’s why, today, a harmless Hindu ritual and the act of emotionally or physically assaulting a Muslim, may carry similar performative connotations. For example, a militant Hindu nationalist mob attacking a Muslim can be conceived by the attackers as a sacred ritual.

Same is the case in Pakistan. The researcher Muhammad Amir Rana has conducted several interviews of young Islamist militants who were arrested and put in rehabilitation programmes. Almost all of them were told by their ‘handlers’ that self-sacrifice was a means to create an Islamic state/caliphate that would wipe out poverty, corruption and immorality, and provide justice. This idea was programmed into them to create a ‘self’ in relation to an opposite or ‘the other’. The other in this respect were heretics and infidels who were conspiring to destroy Islam.

When an Islamist suicide bomber explodes him/herself in public, or when extremists desecrate Ahmadiyya graves, or a mob attacks an alleged blasphemer, each one of these believe they are undertaking a sacred ritual that is not that different from the harmless ones. But Islamist militants are not populists. They have dogmatic doctrines or are deeply indoctrinated.

Not so, the populists. Populists are great hijackers of ideas. There’s nothing original or deep about them. Everything remains on the surface. Take, for instance, the recently ousted Pakistani PM Imran Khan. He unabashedly steals ideas from the left and the right. His core constituency, which is not so attuned to history, perceives these ideas as being entirely new. Everything he says or claims to have done, becomes ‘for the first time in the history of Pakistan.’

But being a populist, it wasn’t enough for Khan to frame his ‘struggle’ (against ‘corrupt elites’) as a noble cause. It needed to be manifested as a sacred conviction. So, from 2014 onwards, he increasingly began to lace his speeches with allusions of him fighting for justice and morality by treading a path laid out by Islam’s sacred texts and personalities. He then began to explain this undertaking as a ‘jihad’.

These were/are pure populist manoeuvres and entirely performative. Once the cause transformed into becoming a ‘jihad’, it not only required rhetoric culled from Islamist evangelists and then put in the context of a ‘political struggle’, but it also needed performed piety — carrying prayer beads, being constantly photographed while saying obligatory Muslim prayers, embracing famous preachers, etc.

And since ‘jihad’ in the popular imagination is often perceived to be something aggressive and manly, Khan poses as an outspoken and fearless saviour of not only the people of Pakistan, but also of the ‘ummah’.

Yet, by all accounts, he is not very religious. He’s not secular either. But this is how populists are. They are basically nothing. They are great performers who can draw devotion from a great many people — especially those who are struggling to formulate a political identity for themselves. There are no shortcuts to this. But populists provide them shortcuts.

Khan is a curious mixture of an Islamist and a brawler. But both of these attributes mainly reside on the surface and in his rhetoric. The only aim one can say that is lingering underneath the surface is an inexhaustible ambition to be constantly admired and, of course, rule as a North Korean premier does. Conjuring lots of adulation, but zero opposition.

Thursday 31 March 2022

Monday 3 January 2022

Can you think yourself young?

Research shows that a positive attitude to ageing can lead to a longer, healthier life, while negative beliefs can have hugely detrimental effects by David Robson in the Guardian

For more than a decade, Paddy Jones has been wowing audiences across the world with her salsa dancing. She came to fame on the Spanish talent show Tú Sí Que Vales (You’re Worth It) in 2009 and has since found success in the UK, through Britain’s Got Talent; in Germany, on Das Supertalent; in Argentina, on the dancing show Bailando; and in Italy, where she performed at the Sanremo music festival in 2018 alongside the band Lo Stato Sociale.

Jones also happens to be in her mid-80s, making her the world’s oldest acrobatic salsa dancer, according to Guinness World Records. Growing up in the UK, Jones had been a keen dancer and had performed professionally before she married her husband, David, at 22 and had four children. It was only in retirement that she began dancing again – to widespread acclaim. “I don’t plead my age because I don’t feel 80 or act it,” Jones told an interviewer in 2014.

According to a wealth of research that now spans five decades, we would all do well to embrace the same attitude – since it can act as a potent elixir of life. People who see the ageing process as a potential for personal growth tend to enjoy much better health into their 70s, 80s and 90s than people who associate ageing with helplessness and decline, differences that are reflected in their cells’ biological ageing and their overall life span.

Salsa dancer Paddy Jones, centre. Photograph: Alberto Terenghi/IPA/Shutterstock

Salsa dancer Paddy Jones, centre. Photograph: Alberto Terenghi/IPA/Shutterstock

Of all the claims I have investigated for my new book on the mind-body connection, the idea that our thoughts could shape our ageing and longevity was by far the most surprising. The science, however, turns out to be incredibly robust. “There’s just such a solid base of literature now,” says Prof Allyson Brothers at Colorado State University. “There are different labs in different countries using different measurements and different statistical approaches and yet the answer is always the same.”

If I could turn back time

The first hints that our thoughts and expectations could either accelerate or decelerate the ageing process came from a remarkable experiment by the psychologist Ellen Langer at Harvard University.

In 1979, she asked a group of 70- and 80-year-olds to complete various cognitive and physical tests, before taking them to a week-long retreat at a nearby monastery that had been redecorated in the style of the late 1950s. Everything at the location, from the magazines in the living room to the music playing on the radio and the films available to watch, was carefully chosen for historical accuracy.If you believe that you are frail and helpless, small difficulties will start to feel more threatening

The researchers asked the participants to live as if it were 1959. They had to write a biography of themselves for that era in the present tense and they were told to act as independently as possible. (They were discouraged from asking for help to carry their belongings to their room, for example.) The researchers also organised twice-daily discussions in which the participants had to talk about the political and sporting events of 1959 as if they were currently in progress – without talking about events since that point. The aim was to evoke their younger selves through all these associations.

To create a comparison, the researchers ran a second retreat a week later with a new set of participants. While factors such as the decor, diet and social contact remained the same, these participants were asked to reminisce about the past, without overtly acting as if they were reliving that period.

Most of the participants showed some improvements from the baseline tests to the after-retreat ones, but it was those in the first group, who had more fully immersed themselves in the world of 1959, who saw the greatest benefits. Sixty-three per cent made a significant gain on the cognitive tests, for example, compared to just 44% in the control condition. Their vision became sharper, their joints more flexible and their hands more dextrous, as some of the inflammation from their arthritis receded. As enticing as these findings might seem, Langer’s was based on a very small sample size. Extraordinary claims need extraordinary evidence and the idea that our mindset could somehow influence our physical ageing is about as extraordinary as scientific theories come.

Becca Levy, at the Yale School of Public Health, has been leading the way to provide that proof. In one of her earliest – and most eye-catching – papers, she examined data from the Ohio Longitudinal Study of Aging and Retirement that examined more than 1,000 participants since 1975.

The participants’ average age at the start of the survey was 63 years old and soon after joining they were asked to give their views on ageing. For example, they were asked to rate their agreement with the statement: “As you get older, you are less useful”. Quite astonishingly, Levy found the average person with a more positive attitude lived on for 22.6 years after the study commenced, while the average person with poorer interpretations of ageing survived for just 15 years. That link remained even after Levy had controlled for their actual health status at the start of the survey, as well as other known risk factors, such as socioeconomic status or feelings of loneliness, which could influence longevity.

The implications of the finding are as remarkable today as they were in 2002, when the study was first published. “If a previously unidentified virus was found to diminish life expectancy by over seven years, considerable effort would probably be devoted to identifying the cause and implementing a remedy,” Levy and her colleagues wrote. “In the present case, one of the likely causes is known: societally sanctioned denigration of the aged.”

Later studies have since reinforced the link between people’s expectations and their physical ageing, while dismissing some of the more obvious – and less interesting – explanations. You might expect that people’s attitudes would reflect their decline rather than contribute to the degeneration, for example. Yet many people will endorse certain ageist beliefs, such as the idea that “old people are helpless”, long before they should have started experiencing age-related disability themselves. And Levy has found that those kinds of views, expressed in people’s mid-30s, can predict their subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease up to 38 years later.

The most recent findings suggest that age beliefs may play a key role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Tracking 4,765 participants over four years, the researchers found that positive expectations of ageing halved the risk of developing the disease, compared to those who saw old age as an inevitable period of decline. Astonishingly, this was even true of people who carried a harmful variant of the APOE gene, which is known to render people more susceptible to the disease. The positive mindset can counteract an inherited misfortune, protecting against the build-up of the toxic plaques and neuronal loss that characterise the disease.

How could this be?

Behaviour is undoubtedly important. If you associate age with frailty and disability, you may be less likely to exercise as you get older and that lack of activity is certainly going to increase your predisposition to many illnesses, including heart disease and Alzheimer’s.

Our culture is saturated with messages that reinforce the damaging age beliefs. Just consider greetings cards

Importantly, however, our age beliefs can also have a direct effect on our physiology. Elderly people who have been primed with negative age stereotypes tend to have higher systolic blood pressure in response to challenges, while those who have seen positive stereotypes demonstrate a more muted reaction. This makes sense: if you believe that you are frail and helpless, small difficulties will start to feel more threatening. Over the long term, this heightened stress response increases levels of the hormone cortisol and bodily inflammation, which could both raise the risk of ill health.

The consequences can even be seen within the nuclei of the individual cells, where our genetic blueprint is stored. Our genes are wrapped tightly in each cell’s chromosomes, which have tiny protective caps, called telomeres, which keep the DNA stable and stop it from becoming frayed and damaged. Telomeres tend to shorten as we age and this reduces their protective abilities and can cause the cell to malfunction. In people with negative age beliefs, that process seems to be accelerated - their cells look biologically older. In those with the positive attitudes, it is much slower - their cells look younger.

For many scientists, the link between age beliefs and long-term health and longevity is practically beyond doubt. “It’s now very well established,” says Dr David Weiss, who studies the psychology of ageing at Martin-Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany. And it has critical implications for people of all generations.

Birthday cards sent to Captain Tom Moore for his 100th birthday – many cards for older people have a less respectful tone. Photograph: Shaun Botterill/Getty Images

Birthday cards sent to Captain Tom Moore for his 100th birthday – many cards for older people have a less respectful tone. Photograph: Shaun Botterill/Getty Images

Our culture is saturated with messages that reinforce the damaging age beliefs. Just consider greetings cards, which commonly play on of images depicting confused and forgetful older people. “The other day, I went to buy a happy 70th birthday card for a friend and I couldn’t find a single one that wasn’t a joke,” says Martha Boudreau, the chief communications officer of AARP, a special interest group (formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons) that focuses on the issues of over-50s.

She would like to see greater awareness – and intolerance – of age stereotypes, in much the same way that people now show greater sensitivity to sexism and racism. “Celebrities, thought leaders and influencers need to step forward,” says Boudreau.

In the meantime, we can try to rethink our perceptions of our own ageing. Various studies show that our mindsets are malleable. By learning to reject fatalistic beliefs and appreciate some of the positive changes that come with age, we may avoid the amplified stress responses that arise from exposure to negative stereotypes and we may be more motivated to exercise our bodies and minds and to embrace new challenges.

We could all, in other words, learn to live like Paddy Jones.

When I interviewed Jones, she was careful to emphasise the potential role of luck in her good health. But she agrees that many people have needlessly pessimistic views of their capabilities, over what could be their golden years, and encourages them to question the supposed limits. “If you feel there’s something you want to do, and it inspires you, try it!” she told me. “And if you find you can’t do it, then look for something else you can achieve.”

Whatever our current age, that’s surely a winning attitude that will set us up for greater health and happiness for decades to come.

For more than a decade, Paddy Jones has been wowing audiences across the world with her salsa dancing. She came to fame on the Spanish talent show Tú Sí Que Vales (You’re Worth It) in 2009 and has since found success in the UK, through Britain’s Got Talent; in Germany, on Das Supertalent; in Argentina, on the dancing show Bailando; and in Italy, where she performed at the Sanremo music festival in 2018 alongside the band Lo Stato Sociale.

Jones also happens to be in her mid-80s, making her the world’s oldest acrobatic salsa dancer, according to Guinness World Records. Growing up in the UK, Jones had been a keen dancer and had performed professionally before she married her husband, David, at 22 and had four children. It was only in retirement that she began dancing again – to widespread acclaim. “I don’t plead my age because I don’t feel 80 or act it,” Jones told an interviewer in 2014.

According to a wealth of research that now spans five decades, we would all do well to embrace the same attitude – since it can act as a potent elixir of life. People who see the ageing process as a potential for personal growth tend to enjoy much better health into their 70s, 80s and 90s than people who associate ageing with helplessness and decline, differences that are reflected in their cells’ biological ageing and their overall life span.

Salsa dancer Paddy Jones, centre. Photograph: Alberto Terenghi/IPA/Shutterstock

Salsa dancer Paddy Jones, centre. Photograph: Alberto Terenghi/IPA/ShutterstockOf all the claims I have investigated for my new book on the mind-body connection, the idea that our thoughts could shape our ageing and longevity was by far the most surprising. The science, however, turns out to be incredibly robust. “There’s just such a solid base of literature now,” says Prof Allyson Brothers at Colorado State University. “There are different labs in different countries using different measurements and different statistical approaches and yet the answer is always the same.”

If I could turn back time

The first hints that our thoughts and expectations could either accelerate or decelerate the ageing process came from a remarkable experiment by the psychologist Ellen Langer at Harvard University.

In 1979, she asked a group of 70- and 80-year-olds to complete various cognitive and physical tests, before taking them to a week-long retreat at a nearby monastery that had been redecorated in the style of the late 1950s. Everything at the location, from the magazines in the living room to the music playing on the radio and the films available to watch, was carefully chosen for historical accuracy.If you believe that you are frail and helpless, small difficulties will start to feel more threatening

The researchers asked the participants to live as if it were 1959. They had to write a biography of themselves for that era in the present tense and they were told to act as independently as possible. (They were discouraged from asking for help to carry their belongings to their room, for example.) The researchers also organised twice-daily discussions in which the participants had to talk about the political and sporting events of 1959 as if they were currently in progress – without talking about events since that point. The aim was to evoke their younger selves through all these associations.

To create a comparison, the researchers ran a second retreat a week later with a new set of participants. While factors such as the decor, diet and social contact remained the same, these participants were asked to reminisce about the past, without overtly acting as if they were reliving that period.

Most of the participants showed some improvements from the baseline tests to the after-retreat ones, but it was those in the first group, who had more fully immersed themselves in the world of 1959, who saw the greatest benefits. Sixty-three per cent made a significant gain on the cognitive tests, for example, compared to just 44% in the control condition. Their vision became sharper, their joints more flexible and their hands more dextrous, as some of the inflammation from their arthritis receded. As enticing as these findings might seem, Langer’s was based on a very small sample size. Extraordinary claims need extraordinary evidence and the idea that our mindset could somehow influence our physical ageing is about as extraordinary as scientific theories come.

Becca Levy, at the Yale School of Public Health, has been leading the way to provide that proof. In one of her earliest – and most eye-catching – papers, she examined data from the Ohio Longitudinal Study of Aging and Retirement that examined more than 1,000 participants since 1975.

The participants’ average age at the start of the survey was 63 years old and soon after joining they were asked to give their views on ageing. For example, they were asked to rate their agreement with the statement: “As you get older, you are less useful”. Quite astonishingly, Levy found the average person with a more positive attitude lived on for 22.6 years after the study commenced, while the average person with poorer interpretations of ageing survived for just 15 years. That link remained even after Levy had controlled for their actual health status at the start of the survey, as well as other known risk factors, such as socioeconomic status or feelings of loneliness, which could influence longevity.

The implications of the finding are as remarkable today as they were in 2002, when the study was first published. “If a previously unidentified virus was found to diminish life expectancy by over seven years, considerable effort would probably be devoted to identifying the cause and implementing a remedy,” Levy and her colleagues wrote. “In the present case, one of the likely causes is known: societally sanctioned denigration of the aged.”

Later studies have since reinforced the link between people’s expectations and their physical ageing, while dismissing some of the more obvious – and less interesting – explanations. You might expect that people’s attitudes would reflect their decline rather than contribute to the degeneration, for example. Yet many people will endorse certain ageist beliefs, such as the idea that “old people are helpless”, long before they should have started experiencing age-related disability themselves. And Levy has found that those kinds of views, expressed in people’s mid-30s, can predict their subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease up to 38 years later.

The most recent findings suggest that age beliefs may play a key role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Tracking 4,765 participants over four years, the researchers found that positive expectations of ageing halved the risk of developing the disease, compared to those who saw old age as an inevitable period of decline. Astonishingly, this was even true of people who carried a harmful variant of the APOE gene, which is known to render people more susceptible to the disease. The positive mindset can counteract an inherited misfortune, protecting against the build-up of the toxic plaques and neuronal loss that characterise the disease.

How could this be?

Behaviour is undoubtedly important. If you associate age with frailty and disability, you may be less likely to exercise as you get older and that lack of activity is certainly going to increase your predisposition to many illnesses, including heart disease and Alzheimer’s.

Our culture is saturated with messages that reinforce the damaging age beliefs. Just consider greetings cards

Importantly, however, our age beliefs can also have a direct effect on our physiology. Elderly people who have been primed with negative age stereotypes tend to have higher systolic blood pressure in response to challenges, while those who have seen positive stereotypes demonstrate a more muted reaction. This makes sense: if you believe that you are frail and helpless, small difficulties will start to feel more threatening. Over the long term, this heightened stress response increases levels of the hormone cortisol and bodily inflammation, which could both raise the risk of ill health.

The consequences can even be seen within the nuclei of the individual cells, where our genetic blueprint is stored. Our genes are wrapped tightly in each cell’s chromosomes, which have tiny protective caps, called telomeres, which keep the DNA stable and stop it from becoming frayed and damaged. Telomeres tend to shorten as we age and this reduces their protective abilities and can cause the cell to malfunction. In people with negative age beliefs, that process seems to be accelerated - their cells look biologically older. In those with the positive attitudes, it is much slower - their cells look younger.

For many scientists, the link between age beliefs and long-term health and longevity is practically beyond doubt. “It’s now very well established,” says Dr David Weiss, who studies the psychology of ageing at Martin-Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany. And it has critical implications for people of all generations.

Birthday cards sent to Captain Tom Moore for his 100th birthday – many cards for older people have a less respectful tone. Photograph: Shaun Botterill/Getty Images

Birthday cards sent to Captain Tom Moore for his 100th birthday – many cards for older people have a less respectful tone. Photograph: Shaun Botterill/Getty ImagesOur culture is saturated with messages that reinforce the damaging age beliefs. Just consider greetings cards, which commonly play on of images depicting confused and forgetful older people. “The other day, I went to buy a happy 70th birthday card for a friend and I couldn’t find a single one that wasn’t a joke,” says Martha Boudreau, the chief communications officer of AARP, a special interest group (formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons) that focuses on the issues of over-50s.

She would like to see greater awareness – and intolerance – of age stereotypes, in much the same way that people now show greater sensitivity to sexism and racism. “Celebrities, thought leaders and influencers need to step forward,” says Boudreau.

In the meantime, we can try to rethink our perceptions of our own ageing. Various studies show that our mindsets are malleable. By learning to reject fatalistic beliefs and appreciate some of the positive changes that come with age, we may avoid the amplified stress responses that arise from exposure to negative stereotypes and we may be more motivated to exercise our bodies and minds and to embrace new challenges.

We could all, in other words, learn to live like Paddy Jones.

When I interviewed Jones, she was careful to emphasise the potential role of luck in her good health. But she agrees that many people have needlessly pessimistic views of their capabilities, over what could be their golden years, and encourages them to question the supposed limits. “If you feel there’s something you want to do, and it inspires you, try it!” she told me. “And if you find you can’t do it, then look for something else you can achieve.”

Whatever our current age, that’s surely a winning attitude that will set us up for greater health and happiness for decades to come.

Sunday 14 November 2021

Wednesday 30 June 2021

Sunday 24 May 2020

Thursday 10 January 2019

Thursday 9 August 2018

Wednesday 25 July 2018

Friday 30 March 2018

What's with the sanctimony, Mr Waugh?

Osman Samiuddin in Cricinfo

Bless our stars, Steve Waugh has weighed in. From his pedestal, perched atop a great moral altitude, he spoke down to us.

"Like many, I'm deeply troubled by the events in Cape Town this last week, and acknowledge the thousands of messages I have received, mostly from heartbroken cricket followers worldwide.

"The Australian Cricket team has always believed it could win in any situation against any opposition, by playing combative, skillful and fair cricket, driven by our pride in the fabled Baggy Green.

"I have no doubt the current Australian team continues to believe in this mantra, however some have now failed our culture, making a serious error of judgement in the Cape Town Test match."

You'll have picked up by now that this was not going to be what it should have been: a mea culpa. "Sorry folks, Cape Town - my bad." One can hope for the tone, but one can't ever imagine such economy with the words.

Waugh's statement was a bid to recalibrate the Australian cricket's team moral compass, and you know, it would have been nice if he acknowledged his role in setting it awry in the first place. Because there can't be any doubt that a clean, straight line runs from the explosion-implosion of Cape Town back to that "culture" that Waugh created for his team, the one cricket gets so reverential about.

First, though, a little pre-reading prep, or YouTube wormholing, just to establish the moral frame within which we are operating. Start with this early in Waugh's international career - claiming a catch at point he clearly dropped off Kris Srikkanth. This was the 1985-86 season and he was young and the umpire spotted it and refused to give it out. So go here. This was ten years later, also at point, and he dropped Brian Lara, though he made as if he juggled and caught it. The umpire duped, Lara gone.![]() Steve Waugh: sanctimonious or statesman-like? Depends on which side of the "line" you stand on Getty Images

Steve Waugh: sanctimonious or statesman-like? Depends on which side of the "line" you stand on Getty Images

A man is not merely the sum of his incidents, and neither does he go through life unchanged. Waugh must have gone on to evolve, right? He became captain of Australia and soon it became clear that he had - all together now, in Morgan Freeman's voice - A Vision. There was a way he wanted his team to play the game.

He spelt it out in 2003, though all it was was a modification of the MCC's existing Spirit of Cricket doctrine. There were commitments to upholding player behaviour, and to how they treated the opposition and umpires, whose decisions they vowed to accept "as a mark of respect for our opponents, the umpires, ourselves and the game".

They would "value honesty and accept that every member of the team has a role to play in shaping and abiding by our shared standards and expectations".

Sledging or abuse would not be condoned. It wasn't enough that Australia played this way - Waugh expected others to do so as well. Here's Nasser Hussain, straight-talking in his memoir on the 2002-03 Ashes in Australia:

"I just think that about this time, he [Waugh] had lost touch with reality a bit he gave me the impression that he had forgotten what playing cricket was like for everyone other than Australia. He became a bit of a preacher. A bit righteous. It was like he expected everyone to do it the Aussie way because their way was the only way."

It was also duplicitous because the Aussie way Waugh was preaching was rarely practised on field by him or his team. So if Hussain refused to walk in the Boxing Day Test in 2002 after Jason Gillespie claimed a catch - with unanimous support from his team - well, you could hardly blame him, right, given Waugh was captain? YouTube wasn't around then, but not much got past Hussain on the field and the chances of those two "catches" having done so are low.

"Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism that has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy"

As for the sledging that Waugh and his men agreed to not condone, revisit Graeme Smith's comments from the first time he played Australia, in 2001-02, with Waugh as captain. There's no need to republish it here but you can read about it (and keep kids away from the screen). It's not clever.

No, Waugh's sides didn't really show that much respect to opponents, unless their version of respect was Glenn McGrath asking Ramnaresh Sarwan - who was getting on top of Australia - what a specific part of Brian Lara's anatomy (no prizes for guessing which one) tasted like.

That incident, in Antigua, is especially instructive today because David Warner v Quinton de Kock is an exact replica. Sarwan's response, referencing McGrath's wife, was reprehensible, just as de Kock's was. But there was zilch recognition from either Warner or McGrath that they had initiated, or gotten involved in, something that could lead to such a comeback, or that their definition of "personal" was, frankly, too fluid and ill-defined for anyone's else's liking.

Waugh wasn't the ODI captain at the time of Darren Lehmann's racist outburstagainst Sri Lanka. Lehmann's captain, however, was Ricky Ponting, Waugh protege and torchbearer of values (and co-creator of the modified Spirit document), and so, historically, this was very much the Waugh era. As an aside, Lehmann's punishment was a five-ODI ban, imposed on him eventually by the ICC; no further sanctions from CA.

It's clear now that this modified code was the Australians drawing their "line", except the contents of the paper were - and continued to be - rendered irrelevant by their actions. The mere existence of it, in Australia's heads, has been enough.

You've got to marvel at the conceit of them taking a universal code and unilaterally modifying it primarily for themselves, not in discussion with, you know, the many other non-Australian stakeholders in cricket - who might view the spirit of the game differently, if at all they give any importance to it - and expecting them to adhere to it.![]() They won trophies, but not hearts Getty Images

They won trophies, but not hearts Getty Images

It's why Warner and McGrath not only could not take it being dished back, but that they saw something intrinsically wrong in receiving it and not dishing it out. It's why it was fine to sledge Sourav Ganguly on rumours about his private life, but Ganguly turning up to the toss late was, in Waugh's words, "disrespectful" - to the game, of course, not him.

Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism, which has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy. Look at the varnish of formality in dousing the true implication of "mental disintegration"; does "illegal combatants" ring a bell?

What took hold after Waugh was not what he preached but what he practised. One of my favourite examples is this lesser-remembered moment involving Justin Langer, a Waugh acolyte through and through, and his surreptitious knocking-off of a bail in Sri Lanka. Whatever he was trying to do, it wasn't valuing honesty as Waugh's code wanted.

Naturally the mind is drawn to the bigger, more infamous occasions, such as the behaviour of Ponting and his side that prompted a brave and stirring calling outby Peter Roebuck. That was two years before Ponting's virtual bullying of Aleem Dar after a decision went against Australia in the Ashes. It sure was a funny way to accept the umpire's decision. Ponting loved pushing another virtuous ploy that could so easily have been a Waugh tenet: of entering into gentlemen's agreements with opposing captains and taking the fielder's word for a disputed catch. Not many opposition captains did, which was telling of the virtuousness sides ascribed to Australia.

That this happened a decade or so ago should, if nothing else, confirm that Cape Town isn't just about the culture within this side - this is a legacy, passed on from the High Priest of Righteousness, Steve Waugh, to Ponting to Michael Clarke to Steve Smith, leaders of a long list of Australian sides that may have been good, bad and great but have been consistently unloved.

It's fair to be sceptical of real change. The severity of CA's sanctions - in response to public outrage and not the misdemeanour itself - amount to another bit of righteous oneupmanship. We remove captains for ball-tampering, what do you do? We, the rest of the world, let the ICC deal with them as per the global code for such things, and in that time the sky didn't fall. Now, on the back of CA's actions, David Richardson wants tougher punishments, thus continuing the ICC's strategy of policy-making based solely on incidents from series involving the Big Three.

Waugh was a great batsman. He was the captain of a great side. The only fact to add to this is that he played the game with great sanctimony. That helps explains why Australia now are where they are.

Bless our stars, Steve Waugh has weighed in. From his pedestal, perched atop a great moral altitude, he spoke down to us.

"Like many, I'm deeply troubled by the events in Cape Town this last week, and acknowledge the thousands of messages I have received, mostly from heartbroken cricket followers worldwide.

"The Australian Cricket team has always believed it could win in any situation against any opposition, by playing combative, skillful and fair cricket, driven by our pride in the fabled Baggy Green.

"I have no doubt the current Australian team continues to believe in this mantra, however some have now failed our culture, making a serious error of judgement in the Cape Town Test match."

You'll have picked up by now that this was not going to be what it should have been: a mea culpa. "Sorry folks, Cape Town - my bad." One can hope for the tone, but one can't ever imagine such economy with the words.

Waugh's statement was a bid to recalibrate the Australian cricket's team moral compass, and you know, it would have been nice if he acknowledged his role in setting it awry in the first place. Because there can't be any doubt that a clean, straight line runs from the explosion-implosion of Cape Town back to that "culture" that Waugh created for his team, the one cricket gets so reverential about.

First, though, a little pre-reading prep, or YouTube wormholing, just to establish the moral frame within which we are operating. Start with this early in Waugh's international career - claiming a catch at point he clearly dropped off Kris Srikkanth. This was the 1985-86 season and he was young and the umpire spotted it and refused to give it out. So go here. This was ten years later, also at point, and he dropped Brian Lara, though he made as if he juggled and caught it. The umpire duped, Lara gone.

A man is not merely the sum of his incidents, and neither does he go through life unchanged. Waugh must have gone on to evolve, right? He became captain of Australia and soon it became clear that he had - all together now, in Morgan Freeman's voice - A Vision. There was a way he wanted his team to play the game.

He spelt it out in 2003, though all it was was a modification of the MCC's existing Spirit of Cricket doctrine. There were commitments to upholding player behaviour, and to how they treated the opposition and umpires, whose decisions they vowed to accept "as a mark of respect for our opponents, the umpires, ourselves and the game".

They would "value honesty and accept that every member of the team has a role to play in shaping and abiding by our shared standards and expectations".

Sledging or abuse would not be condoned. It wasn't enough that Australia played this way - Waugh expected others to do so as well. Here's Nasser Hussain, straight-talking in his memoir on the 2002-03 Ashes in Australia:

"I just think that about this time, he [Waugh] had lost touch with reality a bit he gave me the impression that he had forgotten what playing cricket was like for everyone other than Australia. He became a bit of a preacher. A bit righteous. It was like he expected everyone to do it the Aussie way because their way was the only way."

It was also duplicitous because the Aussie way Waugh was preaching was rarely practised on field by him or his team. So if Hussain refused to walk in the Boxing Day Test in 2002 after Jason Gillespie claimed a catch - with unanimous support from his team - well, you could hardly blame him, right, given Waugh was captain? YouTube wasn't around then, but not much got past Hussain on the field and the chances of those two "catches" having done so are low.

"Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism that has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy"

As for the sledging that Waugh and his men agreed to not condone, revisit Graeme Smith's comments from the first time he played Australia, in 2001-02, with Waugh as captain. There's no need to republish it here but you can read about it (and keep kids away from the screen). It's not clever.

No, Waugh's sides didn't really show that much respect to opponents, unless their version of respect was Glenn McGrath asking Ramnaresh Sarwan - who was getting on top of Australia - what a specific part of Brian Lara's anatomy (no prizes for guessing which one) tasted like.

That incident, in Antigua, is especially instructive today because David Warner v Quinton de Kock is an exact replica. Sarwan's response, referencing McGrath's wife, was reprehensible, just as de Kock's was. But there was zilch recognition from either Warner or McGrath that they had initiated, or gotten involved in, something that could lead to such a comeback, or that their definition of "personal" was, frankly, too fluid and ill-defined for anyone's else's liking.

Waugh wasn't the ODI captain at the time of Darren Lehmann's racist outburstagainst Sri Lanka. Lehmann's captain, however, was Ricky Ponting, Waugh protege and torchbearer of values (and co-creator of the modified Spirit document), and so, historically, this was very much the Waugh era. As an aside, Lehmann's punishment was a five-ODI ban, imposed on him eventually by the ICC; no further sanctions from CA.

It's clear now that this modified code was the Australians drawing their "line", except the contents of the paper were - and continued to be - rendered irrelevant by their actions. The mere existence of it, in Australia's heads, has been enough.

You've got to marvel at the conceit of them taking a universal code and unilaterally modifying it primarily for themselves, not in discussion with, you know, the many other non-Australian stakeholders in cricket - who might view the spirit of the game differently, if at all they give any importance to it - and expecting them to adhere to it.

It's why Warner and McGrath not only could not take it being dished back, but that they saw something intrinsically wrong in receiving it and not dishing it out. It's why it was fine to sledge Sourav Ganguly on rumours about his private life, but Ganguly turning up to the toss late was, in Waugh's words, "disrespectful" - to the game, of course, not him.

Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism, which has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy. Look at the varnish of formality in dousing the true implication of "mental disintegration"; does "illegal combatants" ring a bell?

What took hold after Waugh was not what he preached but what he practised. One of my favourite examples is this lesser-remembered moment involving Justin Langer, a Waugh acolyte through and through, and his surreptitious knocking-off of a bail in Sri Lanka. Whatever he was trying to do, it wasn't valuing honesty as Waugh's code wanted.

Naturally the mind is drawn to the bigger, more infamous occasions, such as the behaviour of Ponting and his side that prompted a brave and stirring calling outby Peter Roebuck. That was two years before Ponting's virtual bullying of Aleem Dar after a decision went against Australia in the Ashes. It sure was a funny way to accept the umpire's decision. Ponting loved pushing another virtuous ploy that could so easily have been a Waugh tenet: of entering into gentlemen's agreements with opposing captains and taking the fielder's word for a disputed catch. Not many opposition captains did, which was telling of the virtuousness sides ascribed to Australia.

That this happened a decade or so ago should, if nothing else, confirm that Cape Town isn't just about the culture within this side - this is a legacy, passed on from the High Priest of Righteousness, Steve Waugh, to Ponting to Michael Clarke to Steve Smith, leaders of a long list of Australian sides that may have been good, bad and great but have been consistently unloved.

It's fair to be sceptical of real change. The severity of CA's sanctions - in response to public outrage and not the misdemeanour itself - amount to another bit of righteous oneupmanship. We remove captains for ball-tampering, what do you do? We, the rest of the world, let the ICC deal with them as per the global code for such things, and in that time the sky didn't fall. Now, on the back of CA's actions, David Richardson wants tougher punishments, thus continuing the ICC's strategy of policy-making based solely on incidents from series involving the Big Three.

Waugh was a great batsman. He was the captain of a great side. The only fact to add to this is that he played the game with great sanctimony. That helps explains why Australia now are where they are.

Thursday 23 November 2017

From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullshit took over

Andre Spicer in The Guardian

In early 1984, executives at the telephone company Pacific Bell made a fateful decision. For decades, the company had enjoyed a virtual monopoly on telephone services in California, but now it was facing a problem. The industry was about to be deregulated, and Pacific Bell would soon be facing tough competition.

The management team responded by doing all the things managers usually do: restructuring, downsizing, rebranding. But for the company executives, this wasn’t enough. They worried that Pacific Bell didn’t have the right culture, that employees did not understand “the profit concept” and were not sufficiently entrepreneurial. If they were to compete in this new world, it was not just their balance sheet that needed an overhaul, the executives decided. Their 23,000 employees needed to be overhauled as well.

The company turned to a well-known organisational development specialist, Charles Krone, who set about designing a management-training programme to transform the way people thought, talked and behaved. The programme was based on the ideas of the 20th-century Russian mystic George Gurdjieff. According to Gurdjieff, most of us spend our days mired in “waking sleep”, and it is only by shedding ingrained habits of thinking that we can liberate our inner potential. Gurdjieff’s mystical ideas originally appealed to members of the modernist avant garde, such as the writer Katherine Mansfield and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. More than 60 years later, senior executives at Pacific Bell were likewise seduced by Gurdjieff’s ideas. The company planned to spend $147m (£111m) putting their employees through the new training programme, which came to be known as Kroning.

Over the course of 10 two-day sessions, staff were instructed in new concepts, such as “the law of three” (a “thinking framework that helps us identify the quality of mental energy we have”), and discovered the importance of “alignment”, “intentionality” and “end-state visions”. This new vocabulary was designed to awake employees from their bureaucratic doze and open their eyes to a new higher-level consciousness. And some did indeed feel like their ability to get things done had improved.

But there were some unfortunate side-effects of this heightened corporate consciousness. First, according to one former middle manager, it was virtually impossible for anyone outside the company to understand this new language the employees were speaking. Second, the manager said, the new language “led to a lot more meetings” and the sheer amount of time wasted nurturing their newfound states of higher consciousness meant that “everything took twice as long”. “If the energy that had been put into Kroning had been put to the business at hand, we all would have gotten a lot more done,” said the manager.

Although Kroning was packaged in the new-age language of psychic liberation, it was backed by all the threats of an authoritarian corporation. Many employees felt they were under undue pressure to buy into Kroning. For instance, one manager was summoned to her superior’s office after a team member walked out of a Kroning session. She was asked to “force out or retire” the rebellious employee.

Some Pacific Bell employees wrote to their congressmen about Kroning. Newspapers ran damning stories with headlines such as “Phone company dabbles in mysticism”. The Californian utility regulator launched a public inquiry, and eventually closed the training course, but not before $40m dollars had been spent.

During this period, a young computer programmer at Pacific Bell was spending his spare time drawing a cartoon that mercilessly mocked the management-speak that had invaded his workplace. The cartoon featured a hapless office drone, his disaffected colleagues, his evil boss and an even more evil management consultant. It was a hit, and the comic strip was syndicated in newspapers across the world. The programmer’s name was Scott Adams, and the series he created was Dilbert. You can still find these images pinned up in thousands of office cubicles around the world today.

Although Kroning may have been killed off, Kronese has lived on. The indecipherable management-speak of which Charles Krone was an early proponent seems to have infected the entire world. These days, Krone’s gobbledygook seems relatively benign compared to much of the vacuous language circulating in the emails and meeting rooms of corporations, government agencies and NGOs. Words like “intentionality” sound quite sensible when compared to “ideation”, “imagineering”, and “inboxing” – the sort of management-speak used to talk about everything from educating children to running nuclear power plants. This language has become a kind of organisational lingua franca, used by middle managers in the same way that freemasons use secret handshakes – to indicate their membership and status. It echoes across the cubicled landscape. It seems to be everywhere, and refer to anything, and nothing.

It hasn’t always been this way. A certain amount of empty talk is unavoidable when humans gather together in large groups, but the kind of bullshit through which we all have to wade every day is a remarkably recent creation. To understand why, we have to look at how management fashions have changed over the past century or so.

In the late 18th century, firms were owned and operated by businesspeople who tended to rely on tradition and instinct to manage their employees. Over the next century, as factories became more common, a new figure appeared: the manager. This new class of boss faced a big problem, albeit one familiar to many people who occupy new positions: they were not taken seriously. To gain respect, managers assumed the trappings of established professions such as doctors and lawyers. They were particularly keen to be seen as a new kind of engineer, so they appropriated the stopwatches and rulers used by them. In the process, they created the first major workplace fashion: scientific management.

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Firms started recruiting efficiency experts to conduct time-and-motion studies. After recording every single movement of a worker in minute detail, the time-and-motion expert would rearrange the worker’s performance of tasks into a more efficient order. Their aim was to make the worker into a well-functioning machine, doing each part of the job in the most efficient way. Scientific management was not limited to the workplaces of the capitalist west – Stalin pushed for similar techniques to be imposed in factories throughout the Soviet Union.

Workers found the new techniques alien, and a backlash inevitably followed. Charlie Chaplin famously satirised the cult of scientific management in his 1936 film Modern Times, which depicts a factory worker who is slowly driven mad by the pressures of life on the production line.

As scientific management became increasingly unpopular, executives began casting around for alternatives. They found inspiration in a famous series of experiments conducted by psychologists in the 1920s at the Hawthorne Works, a factory complex in Illinois where tens of thousands of workers were employed by Western Electric to make telephone equipment. A team of researchers from Harvard had initially set out to discover whether changes in environment, such as adjusting the lighting or temperature, could influence how much workers produced each day.

To their surprise, the researchers found that no matter how light or dark the workplace was, employees continued to work hard. The only thing that seemed to make a difference was the amount of attention that workers got from the experimenters. This insight led one of the researchers, an Australian psychologist called Elton Mayo, to conclude that what he called the “human aspects” of work were far more important than “environmental” factors. While this may seem obvious, it came as news to many executives at the time.

As Mayo’s ideas caught hold, companies attempted to humanise their workplaces. They began talking about human relationships, worker motivation and group dynamics. They started conducting personality testing and running teambuilding exercises: all in the hope of nurturing good human relations in the workplace.

This newfound interest in the human side of work did not last long. During the second world war, as the US and UK military invested heavily in trying to make war more efficient, management fashions began to shift. A bright young Berkeley graduate called Robert McNamara led a US army air forces team that used statistics to plan the most cost-effective way to flatten Japan in bombing campaigns. After the war, many military leaders brought these new techniques into the corporate world. McNamara, for instance, joined the Ford Motor Company, rising quickly to become its CEO, while the mathematical procedures that he had developed during the war were enthusiastically taken up by companies to help plan the best way to deliver cheese, toothpaste and Barbie dolls to American consumers. Today these techniques are known as supply-chain management.

During the postwar years, the individual worker once again became a cog in a large, hierarchical machine. While many of the grey-suited employees at these firms savoured the security, freedom and increasing affluence that their work brought, many also complained about the deep lack of meaning in their lives. The backlash came in the late 1960s, as the youth movement railed against the conformity demanded by big corporations. Protesters sprayed slogans such as “live without dead time” and “to hell with boundaries” on to city walls around the world. They wanted to be themselves, express who they really were, and not have to obey “the Man”.

In response to this cultural change, in the 1970s, management fashions changed again. Executives began attending new-age workshops to help them “self actualise” by unlocking their hidden “human potential”. Companies instigated “encounter groups”, in which employees could explore their deeper inner emotions. Offices were redesigned to look more like university campuses than factories.

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMC

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMC

Nowhere is this shift better captured than in the final episode of the television series Mad Men. Don Draper had been the exemplar of the organisational man, wearing a standard-issue grey suit when we met him at the beginning of the show’s first series. After suffering numerous breakdowns over the intervening years, he finds himself at the Esalen institute in northern California, the home of the human potential movement. Initially, Draper resists. But soon he is sitting in a confessional circle, sobbing as he tells his story. His personal breakthrough leads him to take up meditating and chanting, looking out over the Pacific Ocean. The result of Don Draper’s visit to Esalen isn’t just personal transformation. The final scene shows the now-liberated adman’s new creation – an iconic Coca-Cola commercial in which a multiracial group of children stand on a hilltop singing about how they would like to buy the world a Coke and drink it in perfect harmony.

After the fictional Don Draper visited Esalen, work became a place you could go to find yourself. Corporate mission statements now sounded like the revolutionary graffiti of the 1960s. The company training programme run by Charles Krone at Pacific Bell came straight from the Esalen playbook.

Since new-age ideas first permeated the workplace in the 1970s, the spin cycle of management-speak has sped up. During the 1980s, management experts went in search of fresh ideas in Japan. Management became a kind of martial art, with executives visiting “quality dojos” to earn “lean black-belts”. In their 1982 bestseller, In Search of Excellence, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman – both employees of McKinsey, the huge management consultancy agency – recommended that firms foster the same commitment to the company that they found among Honda employees in Japan. The book included the story of one Japanese employee who happens upon a damaged Honda on a public street. He stops and immediately begins repairing the car. The reason? He can’t bear to see a Honda that isn’t perfect.

While McKinsey consultants were mining the wisdom of the east, the ideas of Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen started to find favour among Wall Street financiers. Jensen saw the corporation as a portfolio of assets. Even people – labelled as “human resources” – were part of this portfolio. Each company existed to create returns for shareholders, and if managers failed to do this, they should be fired. If a company didn’t generate adequate returns, it should be broken up and sold off. Every little part of the company was seen as a business. Seduced by this view, many organisations started creating “internal markets”. In the 1990s, under director general John Birt, the BBC created a system in which everything from time in a recording studio to toilet cleaning was traded on a complex internal market. The number of accountants working for the broadcaster exploded, while people who created TV and radio shows were laid off.

As companies have become increasingly ravenous for the latest management fad, they have also become less discerning. Some bizarre recent trends include equine-assisted coaching (“You can lead people, but can you lead a horse?”) and rage rooms (a room where employees can go to take out their frustrations by smashing up office furniture, computers and images of their boss).

A century of management fads has created workplaces that are full of empty words and equally empty rituals. We have to live with the consequences of this history every day. Consider a meeting I recently attended. During the course of an hour, I recorded 64 different nuggets of corporate claptrap. They included familiar favourites such as “doing a deep dive”, “reaching out”, and “thought leadership”. There were also some new ones I hadn’t heard before: people with “protected characteristics” (anyone who wasn’t a white straight guy), “the aha effect” (realising something), “getting our friends in the tent” (getting support from others).

After the meeting, I found myself wondering why otherwise smart people so easily slipped into this kind of business bullshit. How had this obfuscatory way of speaking become so successful? There are a number of familiar and credible explanations. People use management-speak to give the impression of expertise. The inherent vagueness of this language also helps us dodge tough questions. Then there is the simple fact that even if business bullshit annoys many people, in most work situations we try our hardest to be polite and avoid confrontation. So instead of causing a scene by questioning the bullshit flying around the room, I followed the example of Simon Harwood, the director of strategic governance in the BBC’s self-satirising TV sitcom W1A. I used his standard response to any idea – no matter how absurd – “hurrah”.

Still, these explanations did not seem to fully account for the conquest of bullshit. I came across one further explanation in a short article by the anthropologist David Graeber. As factories producing goods in the west have been dismantled, and their work outsourced or replaced with automation, large parts of western economies have been left with little to do. In the 1970s, some sociologists worried that this would lead to a world in which people would need to find new ways to fill their time. The great tragedy for many is that just the opposite seems to have happened.

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBC

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBC

At the very point when work seemed to be withering away, we all became obsessed with it. To be a good citizen, you need to be a productive citizen. There is only one problem, of course: there is less than ever that actually needs to be produced. As Graeber pointed out, the answer has come in the form of what he calls “bullshit jobs”. These are jobs in which people experience their work as “utterly meaningless, contributing nothing to the world”. In a YouGov poll conducted in 2015, 37% of respondents in the UK said their job made no meaningful contribution to the world. But people working in bullshit jobs need to do something. And that something is usually the production, distribution and consumption of bullshit. According to a 2014 survey by the polling agency Harris, the average US employee now spends 45% of their working day doing their real job. The other 55% is spent doing things such as wading through endless emails or attending pointless meetings. Many employees have extended their working day so they can stay late to do their “real work”.

One thing continued to puzzle me: why was it that so many people were paid to do this kind of empty work. One reason that David Graeber gives, in his book The Utopia of Rules, is rampant bureaucracy: there are more forms to be filled in, procedures to be followed and standards to be complied with than ever. Today, bureaucracy comes cloaked in the language of change. Organisations are full of people whose job is to create change for no real reason.

Manufacturing hollow change requires a constant supply of new management fads and fashions. Fortunately, there is a massive industry of business bullshit merchants who are quite happy to supply it. For each new change, new bullshit is needed. Looking back over the list of business bullshit I had noted down during the meeting, I realised that much of it was directly related to empty new bureaucratic initiatives, which were seen as terribly urgent, but would probably be forgotten about in a few years’ time.

One of the corrosive effects of business bullshit can be seen in the statistic that 43% of all teachers in England are considering quitting in the next five years. The most frequently cited reasons are increasingly heavy workloads caused by excessive administration, and a lack of time and space to devote to educating students. A remarkably similar picture appears if you look at the healthcare sector: in the UK, 81% of senior doctors say they are considering retiring from their job early; 57% of GPs are considering leaving the profession; 66% of nurses say they would quit if they could. In each case, the most frequently cited reason is stress caused by increasing managerial demands, and lack of time to do their job properly.

It is not just employees who feel overwhelmed. During the 1980s, when Kroning was in full swing, empty management-speak was confined to the beige meeting rooms of large corporations. Now, it has seeped into every aspect of life. Politicians use business balderdash to avoid grappling with important issues. The machinery of state has also come down with the word-virus. The NHS is crawling with “quality sensei”, “lean ninjas”, and “blue-sky thinkers”. Even schools are flooded with the latest business buzzwords like “grit”, “flipped learning” and “mastery”. Naturally, the kids are learning fast. One teacher recalled how a seven-year-old described her day at school: “Well, when we get to class, we get out our books and start on our non-negotiables.”

In the introduction to his 2015 book, Trust Me, PR Is Dead, the former PR executive Robert Phillips tells a fascinating story. One day he was called up by the CEO of a global corporation. The CEO was worried. A factory which was part of his firm’s supply chain had caught fire and 100 women had burned to death. “My chairman’s been giving me grief,” said the CEO. “He thinks we’re failing to get our message across. We are not emphasising our CSR [corporate social responsibility] credentials well enough.” Phillips responded: “While 100 women’s bodies are still smouldering?” The CEO was “struggling to contain both incredulity and temper”. “I know,” he said. “Please help.” Phillips responded: “You start with actions, not words.”

In many ways, this one interaction tells us how bullshit is used in corporate life. Individual executives facing a problem know that turning to bullshit is probably not the best idea. However, they feel compelled. The problem is that such compulsions often cloud people’s best judgements. They start to think empty words will trump reasonable reflection and considered action. Sadly, in many contexts, empty words win out.

If we hope to improve organisational life – and the wider impact that organisations have on our society – then a good place to start is by reducing the amount of bullshit our organisations produce. Business bullshit allows us to blather on without saying anything. It empties out language and makes us less able to think clearly and soberly about the real issues. As we find our words become increasingly meaningless, we begin to feel a sense of powerlessness. We start to feel there is little we can do apart from play along, benefit from the game and have the occasional laugh.

But this does not need to be the case. Business bullshit can and should be challenged. This is a task each of us can take up by refusing to use empty management-speak. We can stop ourselves from being one more conduit in its circulation. Instead of just rolling our eyes and checking our emails, we should demand something more meaningful.

Clearly, our own individual efforts are not enough. Putting management-speak in its place is going to require a collective effort. What we need is an anti-bullshit movement. It would be made up of people from all walks of life who are dedicated to rooting out empty language. It would question management twaddle in government, in popular culture, in the private sector, in education and in our private lives.

The aim would not just be bullshit-spotting. It would also be a way of reminding people that each of our institutions has its own language and rich set of traditions which are being undermined by the spread of the empty management-speak. It would try to remind people of the power which speech and ideas can have when they are not suffocated with bullshit. By cleaning out the bullshit, it might become possible to have much better functioning organisations and institutions and richer and fulfilling lives.

In early 1984, executives at the telephone company Pacific Bell made a fateful decision. For decades, the company had enjoyed a virtual monopoly on telephone services in California, but now it was facing a problem. The industry was about to be deregulated, and Pacific Bell would soon be facing tough competition.

The management team responded by doing all the things managers usually do: restructuring, downsizing, rebranding. But for the company executives, this wasn’t enough. They worried that Pacific Bell didn’t have the right culture, that employees did not understand “the profit concept” and were not sufficiently entrepreneurial. If they were to compete in this new world, it was not just their balance sheet that needed an overhaul, the executives decided. Their 23,000 employees needed to be overhauled as well.

The company turned to a well-known organisational development specialist, Charles Krone, who set about designing a management-training programme to transform the way people thought, talked and behaved. The programme was based on the ideas of the 20th-century Russian mystic George Gurdjieff. According to Gurdjieff, most of us spend our days mired in “waking sleep”, and it is only by shedding ingrained habits of thinking that we can liberate our inner potential. Gurdjieff’s mystical ideas originally appealed to members of the modernist avant garde, such as the writer Katherine Mansfield and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. More than 60 years later, senior executives at Pacific Bell were likewise seduced by Gurdjieff’s ideas. The company planned to spend $147m (£111m) putting their employees through the new training programme, which came to be known as Kroning.

Over the course of 10 two-day sessions, staff were instructed in new concepts, such as “the law of three” (a “thinking framework that helps us identify the quality of mental energy we have”), and discovered the importance of “alignment”, “intentionality” and “end-state visions”. This new vocabulary was designed to awake employees from their bureaucratic doze and open their eyes to a new higher-level consciousness. And some did indeed feel like their ability to get things done had improved.

But there were some unfortunate side-effects of this heightened corporate consciousness. First, according to one former middle manager, it was virtually impossible for anyone outside the company to understand this new language the employees were speaking. Second, the manager said, the new language “led to a lot more meetings” and the sheer amount of time wasted nurturing their newfound states of higher consciousness meant that “everything took twice as long”. “If the energy that had been put into Kroning had been put to the business at hand, we all would have gotten a lot more done,” said the manager.

Although Kroning was packaged in the new-age language of psychic liberation, it was backed by all the threats of an authoritarian corporation. Many employees felt they were under undue pressure to buy into Kroning. For instance, one manager was summoned to her superior’s office after a team member walked out of a Kroning session. She was asked to “force out or retire” the rebellious employee.

Some Pacific Bell employees wrote to their congressmen about Kroning. Newspapers ran damning stories with headlines such as “Phone company dabbles in mysticism”. The Californian utility regulator launched a public inquiry, and eventually closed the training course, but not before $40m dollars had been spent.

During this period, a young computer programmer at Pacific Bell was spending his spare time drawing a cartoon that mercilessly mocked the management-speak that had invaded his workplace. The cartoon featured a hapless office drone, his disaffected colleagues, his evil boss and an even more evil management consultant. It was a hit, and the comic strip was syndicated in newspapers across the world. The programmer’s name was Scott Adams, and the series he created was Dilbert. You can still find these images pinned up in thousands of office cubicles around the world today.

Although Kroning may have been killed off, Kronese has lived on. The indecipherable management-speak of which Charles Krone was an early proponent seems to have infected the entire world. These days, Krone’s gobbledygook seems relatively benign compared to much of the vacuous language circulating in the emails and meeting rooms of corporations, government agencies and NGOs. Words like “intentionality” sound quite sensible when compared to “ideation”, “imagineering”, and “inboxing” – the sort of management-speak used to talk about everything from educating children to running nuclear power plants. This language has become a kind of organisational lingua franca, used by middle managers in the same way that freemasons use secret handshakes – to indicate their membership and status. It echoes across the cubicled landscape. It seems to be everywhere, and refer to anything, and nothing.

It hasn’t always been this way. A certain amount of empty talk is unavoidable when humans gather together in large groups, but the kind of bullshit through which we all have to wade every day is a remarkably recent creation. To understand why, we have to look at how management fashions have changed over the past century or so.

In the late 18th century, firms were owned and operated by businesspeople who tended to rely on tradition and instinct to manage their employees. Over the next century, as factories became more common, a new figure appeared: the manager. This new class of boss faced a big problem, albeit one familiar to many people who occupy new positions: they were not taken seriously. To gain respect, managers assumed the trappings of established professions such as doctors and lawyers. They were particularly keen to be seen as a new kind of engineer, so they appropriated the stopwatches and rulers used by them. In the process, they created the first major workplace fashion: scientific management.

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/CinetextFirms started recruiting efficiency experts to conduct time-and-motion studies. After recording every single movement of a worker in minute detail, the time-and-motion expert would rearrange the worker’s performance of tasks into a more efficient order. Their aim was to make the worker into a well-functioning machine, doing each part of the job in the most efficient way. Scientific management was not limited to the workplaces of the capitalist west – Stalin pushed for similar techniques to be imposed in factories throughout the Soviet Union.

Workers found the new techniques alien, and a backlash inevitably followed. Charlie Chaplin famously satirised the cult of scientific management in his 1936 film Modern Times, which depicts a factory worker who is slowly driven mad by the pressures of life on the production line.

As scientific management became increasingly unpopular, executives began casting around for alternatives. They found inspiration in a famous series of experiments conducted by psychologists in the 1920s at the Hawthorne Works, a factory complex in Illinois where tens of thousands of workers were employed by Western Electric to make telephone equipment. A team of researchers from Harvard had initially set out to discover whether changes in environment, such as adjusting the lighting or temperature, could influence how much workers produced each day.

To their surprise, the researchers found that no matter how light or dark the workplace was, employees continued to work hard. The only thing that seemed to make a difference was the amount of attention that workers got from the experimenters. This insight led one of the researchers, an Australian psychologist called Elton Mayo, to conclude that what he called the “human aspects” of work were far more important than “environmental” factors. While this may seem obvious, it came as news to many executives at the time.