'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Greece. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Greece. Show all posts

Tuesday, 16 June 2015

Perhaps the world's conspiracy theorists have been right all along

Alex Proud in The Telegraph

Conspiracy theories used to be so easy.

The Iraq War

Wednesday, 29 April 2015

The austerity delusion. Why does Britain still believe it?

The case for cuts was a lie.

Paul Krugman in The Guardian

In May 2010, as Britain headed into its last general election, elites all across the western world were gripped by austerity fever, a strange malady that combined extravagant fear with blithe optimism. Every country running significant budget deficits – as nearly all were in the aftermath of the financial crisis – was deemed at imminent risk of becoming another Greece unless it immediately began cutting spending and raising taxes. Concerns that imposing such austerity in already depressed economies would deepen their depression and delay recovery were airily dismissed; fiscal probity, we were assured, would inspire business-boosting confidence, and all would be well.

People holding these beliefs came to be widely known in economic circles as“austerians” – a term coined by the economist Rob Parenteau – and for a while the austerian ideology swept all before it.

But that was five years ago, and the fever has long since broken. Greece is now seen as it should have been seen from the beginning – as a unique case, with few lessons for the rest of us. It is impossible for countries such as the US and the UK, which borrow in their own currencies, to experience Greek-style crises, because they cannot run out of money – they can always print more. Even within the eurozone, borrowing costs plunged once the European Central Bank began to do its job and protect its clients against self-fulfilling panics by standing ready to buy government bonds if necessary. As I write this, Italy and Spain have no trouble raising cash – they can borrow at the lowest rates in their history, indeed considerably below those in Britain – and even Portugal’s interest rates are within a whisker of those paid by HM Treasury.

On the other side of the ledger, the benefits of improved confidence failed to make their promised appearance. Since the global turn to austerity in 2010, every country that introduced significant austerity has seen its economy suffer, with the depth of the suffering closely related to the harshness of the austerity. In late 2012, the IMF’s chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, went so far as to issue what amounted to a mea culpa: although his organisation never bought into the notion that austerity would actually boost economic growth, the IMF now believes that it massively understated the damage that spending cuts inflict on a weak economy.

Meanwhile, all of the economic research that allegedly supported the austerity push has been discredited. Widely touted statistical results were, it turned out, based on highly dubious assumptions and procedures – plus a few outright mistakes – and evaporated under closer scrutiny.

It is rare, in the history of economic thought, for debates to get resolved this decisively. The austerian ideology that dominated elite discourse five years ago has collapsed, to the point where hardly anyone still believes it. Hardly anyone, that is, except the coalition that still rules Britain – and most of the British media.

I don’t know how many Britons realise the extent to which their economic debate has diverged from the rest of the western world – the extent to which the UK seems stuck on obsessions that have been mainly laughed out of the discourse elsewhere. George Osborne and David Cameron boast that their policies saved Britain from a Greek-style crisis of soaring interest rates, apparently oblivious to the fact that interest rates are at historic lows all across the western world. The press seizes on Ed Miliband’s failure to mention the budget deficit in a speech as a huge gaffe, a supposed revelation of irresponsibility; meanwhile, Hillary Clinton is talking, seriously, not about budget deficits but about the “fun deficit” facing America’s children.

Is there some good reason why deficit obsession should still rule in Britain, even as it fades away everywhere else? No. This country is not different. The economics of austerity are the same – and the intellectual case as bankrupt – in Britain as everywhere else.

Stimulus and its enemies

hen economic crisis struck the advanced economies in 2008, almost every government – even Germany – introduced some kind of stimulus programme, increasing spending and/or cutting taxes. There was no mystery why: it was all about zero.

hen economic crisis struck the advanced economies in 2008, almost every government – even Germany – introduced some kind of stimulus programme, increasing spending and/or cutting taxes. There was no mystery why: it was all about zero.

Normally, monetary authorities – the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England – can respond to a temporary economic downturn by cutting interest rates; this encourages private spending, especially on housing, and sets the stage for recovery. But there’s a limit to how much they can do in that direction. Until recently, the conventional wisdom was that you couldn’t cut interest rates below zero. We now know that this wasn’t quite right, since many European bonds now pay slightly negative interest. Still, there can’t be much room for sub-zero rates. And if cutting rates all the way to zero isn’t enough to cure what ails the economy, the usual remedy for recession falls short.

So it was in 2008-2009. By late 2008 it was already clear in every major economy that conventional monetary policy, which involves pushing down the interest rate on short-term government debt, was going to be insufficient to fight the financial downdraft. Now what? The textbook answer was and is fiscal expansion: increase government spending both to create jobs directly and to put money in consumers’ pockets; cut taxes to put more money in those pockets.

But won’t this lead to budget deficits? Yes, and that’s actually a good thing. An economy that is depressed even with zero interest rates is, in effect, an economy in which the public is trying to save more than businesses are willing to invest. In such an economy the government does everyone a service by running deficits and giving frustrated savers a chance to put their money to work. Nor does this borrowing compete with private investment. An economy where interest rates cannot go any lower is an economy awash in desired saving with no place to go, and deficit spending that expands the economy is, if anything, likely to lead to higher private investment than would otherwise materialise.

It’s true that you can’t run big budget deficits for ever (although you can do it for a long time), because at some point interest payments start to swallow too large a share of the budget. But it’s foolish and destructive to worry about deficits when borrowing is very cheap and the funds you borrow would otherwise go to waste.

At some point you do want to reverse stimulus. But you don’t want to do it too soon – specifically, you don’t want to remove fiscal support as long as pedal-to-the-metal monetary policy is still insufficient. Instead, you want to wait until there can be a sort of handoff, in which the central bank offsets the effects of declining spending and rising taxes by keeping rates low. As John Maynard Keynes wrote in 1937: “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.”

All of this is standard macroeconomics. I often encounter people on both the left and the right who imagine that austerity policies were what the textbook said you should do – that those of us who protested against the turn to austerity were staking out some kind of heterodox, radical position. But the truth is that mainstream, textbook economics not only justified the initial round of post-crisis stimulus, but said that this stimulus should continue until economies had recovered.

What we got instead, however, was a hard right turn in elite opinion, away from concerns about unemployment and toward a focus on slashing deficits, mainly with spending cuts. Why?

Conservatives like to use the alleged dangers of debt and deficits as clubs with which to beat the welfare state and justify cuts in benefits

Part of the answer is that politicians were catering to a public that doesn’t understand the rationale for deficit spending, that tends to think of the government budget via analogies with family finances. When John Boehner, the Republican leader, opposed US stimulus plans on the grounds that “American families are tightening their belt, but they don’t see government tightening its belt,” economists cringed at the stupidity. But within a few months the very same line was showing up in Barack Obama’s speeches, because his speechwriters found that it resonated with audiences. Similarly, the Labour party felt it necessary to dedicate the very first page of its 2015 general election manifesto to a “Budget Responsibility Lock”, promising to “cut the deficit every year”.

Let us not, however, be too harsh on the public. Many elite opinion-makers, including people who imagine themselves sophisticated on matters economic, demonstrated at best a higher level of incomprehension, not getting at all the logic of deficit spending in the face of excess desired saving. For example, in the spring of 2009 the Harvard historian and economic commentator Niall Ferguson, talking about the United States, was quite sure what would happen: “There is going to be, I predict, in the weeks and months ahead, a very painful tug-of-war between our monetary policy and our fiscal policy as the markets realise just what a vast quantity of bonds are going to have to be absorbed by the financial system this year. That will tend to drive the price of the bonds down, and drive up interest rates.” The weeks and months turned into years – six years, at this point – and interest rates remain at historic lows.

Beyond these economic misconceptions, there were political reasons why many influential players opposed fiscal stimulus even in the face of a deeply depressed economy. Conservatives like to use the alleged dangers of debt and deficits as clubs with which to beat the welfare state and justify cuts in benefits; suggestions that higher spending might actually be beneficial are definitely not welcome. Meanwhile, centrist politicians and pundits often try to demonstrate how serious and statesmanlike they are by calling for hard choices and sacrifice (by other people). Even Barack Obama’s first inaugural address, given in the face of a plunging economy, largely consisted of hard-choices boilerplate. As a result, centrists were almost as uncomfortable with the notion of fiscal stimulus as the hard right.

In a way, the remarkable thing about economic policy in 2008-2009 was the fact that the case for fiscal stimulus made any headway at all against the forces of incomprehension and vested interests demanding harsher and harsher austerity. The best explanation of this temporary and limited success I’ve seen comes from the political scientist Henry Farrell, writing with the economist John Quiggin.Farrell and Quiggin note that Keynesian economists were intellectually prepared for the possibility of crisis, in a way that free-market fundamentalists weren’t, and that they were also relatively media-savvy. So they got their take on the appropriate policy response out much more quickly than the other side, creating “the appearance of a new apparent consensus among expert economists” in favour of fiscal stimulus.

If this is right, there was inevitably going to be a growing backlash – a turn against stimulus and toward austerity – once the shock of the crisis wore off. Indeed, there were signs of such a backlash by the early fall of 2009. But the real turning point came at the end of that year, when Greece hit the wall. As a result, the year of Britain’s last general election was also the year of austerity.

Chapter twoThe austerity moment

rom the beginning, there were plenty of people strongly inclined to oppose fiscal stimulus and demand austerity. But they had a problem: their dire warnings about the consequences of deficit spending kept not coming true. Some of them were quite open about their frustration with the refusal of markets to deliver the disasters they expected and wanted. Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, in 2010: “Inflation and long-term interest rates, the typical symptoms of fiscal excess, have remained remarkably subdued. This is regrettable, because it is fostering a sense of complacency that can have dire consequences.”

rom the beginning, there were plenty of people strongly inclined to oppose fiscal stimulus and demand austerity. But they had a problem: their dire warnings about the consequences of deficit spending kept not coming true. Some of them were quite open about their frustration with the refusal of markets to deliver the disasters they expected and wanted. Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, in 2010: “Inflation and long-term interest rates, the typical symptoms of fiscal excess, have remained remarkably subdued. This is regrettable, because it is fostering a sense of complacency that can have dire consequences.”

But he had an answer: “Growing analogies to Greece set the stage for a serious response.” Greece was the disaster austerians were looking for. In September 2009 Greece’s long-term borrowing costs were only 1.3 percentage points higher than Germany’s; by September 2010 that gap had increased sevenfold. Suddenly, austerians had a concrete demonstration of the dangers they had been warning about. A hard turn away from Keynesian policies could now be justified as an urgent defensive measure, lest your country abruptly turn into another Greece.

Still, what about the depressed state of western economies? The post-crisis recession bottomed out in the middle of 2009, and in most countries a recovery was under way, but output and employment were still far below normal. Wouldn’t a turn to austerity threaten the still-fragile upturn?

Not according to many policymakers, who engaged in one of history’s most remarkable displays of collective wishful thinking. Standard macroeconomics said that cutting spending in a depressed economy, with no room to offset these cuts by reducing interest rates that were already near zero, would indeed deepen the slump. But policymakers at the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and in the British government that took power in May 2010 eagerly seized on economic research that claimed to show the opposite.

The doctrine of “expansionary austerity” is largely associated with work byAlberto Alesina, an economist at Harvard. Alesina used statistical techniques that supposedly identified all large fiscal policy changes in advanced countries between 1970 and 2007, and claimed to find evidence that spending cuts, in particular, were often “associated with economic expansions rather than recessions”. The reason, he and those who seized on his work suggested, was that spending cuts create confidence, and that the positive effects of this increase in confidence trump the direct negative effects of reduced spending.

Greece was the disaster austerians were looking for

This may sound too good to be true – and it was. But policymakers knew what they wanted to hear, so it was, as Business Week put it, “Alesina’s hour”. The doctrine of expansionary austerity quickly became orthodoxy in much of Europe. “The idea that austerity measures could trigger stagnation is incorrect,” declared Jean-Claude Trichet, then the president of the European Central Bank, because “confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery”.

Besides, everybody knew that terrible things would happen if debt went above 90% of GDP.

Growth in a Time of Debt, the now-infamous 2010 paper by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University that claimed that 90% debt is a critical threshold, arguably played much less of a direct role in the turn to austerity than Alesina’s work. After all, austerians didn’t need Reinhart and Rogoff to provide dire scenarios about what could happen if deficits weren’t reined in – they had the Greek crisis for that. At most, the Reinhart and Rogoff paper provided a backup bogeyman, an answer to those who kept pointing out that nothing like the Greek story seemed to be happening to countries that borrowed in their own currencies: even if interest rates were low, austerians could point to Reinhart and Rogoff and declare that high debt is very, very bad.

What Reinhart and Rogoff did bring to the austerity camp was academic cachet. Their 2009 book This Time is Different, which brought a vast array of historical data to bear on the subject of economic crises, was widely celebrated by both policymakers and economists – myself included – for its prescient warnings that we were at risk of a major crisis and that recovery from that crisis was likely to be slow. So they brought a lot of prestige to the austerity push when they were perceived as weighing in on that side of the policy debate. (They now claim that they did no such thing, but they did nothing to correct that impression at the time.)

When the coalition government came to power, then, all the pieces were in place for policymakers who were already inclined to push for austerity. Fiscal retrenchment could be presented as urgently needed to avert a Greek-style strike by bond buyers. “Greece stands as a warning of what happens to countries that lose their credibility, or whose governments pretend that difficult decisions can somehow be avoided,” declared David Cameron soon after taking office. It could also be presented as urgently needed to stop debt, already almost 80% of GDP, from crossing the 90% red line. In a 2010 speech laying out his plan to eliminate the deficit, Osborne cited Reinhart and Rogoff by name, while declaring that “soaring government debt ... is very likely to trigger the next crisis.” Concerns about delaying recovery could be waved away with an appeal to positive effects on confidence. Economists who objected to any or all of these lines of argument were simply ignored.

But that was, as I said, five years ago.

Chapter threeDecline and fall of the austerity cult

o understand what happened to austerianism, it helps to start with two charts.

o understand what happened to austerianism, it helps to start with two charts.

The first chart shows interest rates on the bonds of a selection of advanced countries as of mid-April 2015. What you can see right away is that Greece remains unique, more than five years after it was heralded as an object lesson for all nations. Everyone else is paying very low interest rates by historical standards. This includes the United States, where the co-chairs of a debt commission created by President Obama confidently warned that crisis loomed within two years unless their recommendations were adopted; that was four years ago. It includes Spain and Italy, which faced a financial panic in 2011-2012, but saw that panic subside – despite debt that continued to rise – once the European Central Bank began doing its job as lender of last resort. It includes France, which many commentators singled out as the next domino to fall, yet can now borrow long-term for less than 0.5%. And it includes Japan, which has debt more than twice its gross domestic product yet pays even less.

The Greek exception

10-year interest rates as of 14 April 2015

Chart 1Source: Bloomberg

Back in 2010 some economists argued that fears of a Greek-style funding crisis were vastly overblown – I referred to the myth of the “invisible bond vigilantes”. Well, those bond vigilantes have stayed invisible. For countries such as the UK, the US, and Japan that borrow in their own currencies, it’s hard to even see how the predicted crises could happen. Such countries cannot, after all, run out of money, and if worries about solvency weakened their currencies, this would actually help their economies in a time of weak growth and low inflation.

Chart 2 takes a bit more explaining. A couple of years after the great turn towards austerity, a number of economists realised that the austerians were performing what amounted to a great natural experiment. Historically, large cuts in government spending have usually occurred either in overheated economies suffering from inflation or in the aftermath of wars, as nations demobilise. Neither kind of episode offers much guidance on what to expect from the kind of spending cuts – imposed on already depressed economies – that the austerians were advocating. But after 2009, in a generalised economic depression, some countries chose (or were forced) to impose severe austerity, while others did not. So what happened?

Austerity and growth 2009-13

More austere countries have a lower rate of GDP growth

Chart 2Source: IMF

In Chart 2, each dot represents the experience of an advanced economy from 2009 to 2013, the last year of major spending cuts. The horizontal axis shows a widely used measure of austerity – the average annual change in the cyclically adjusted primary surplus, an estimate of what the difference between taxes and non-interest spending would be if the economy were at full employment. As you move further right on the graph, in other words, austerity becomes more severe. You can quibble with the details of this measure, but the basic result – harsh austerity in Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, incredibly harsh austerity in Greece – is surely right.

Meanwhile, the vertical axis shows the annual rate of economic growth over the same period. The negative correlation is, of course, strong and obvious – and not at all what the austerians had asserted would happen.

Again, some economists argued from the beginning that all the talk of expansionary austerity was foolish – back in 2010 I dubbed it belief in the “confidence fairy”, a term that seems to have stuck. But why did the alleged statistical evidence – from Alesina, among others – that spending cuts were often good for growth prove so misleading?

The answer, it turned out, was that it wasn’t very good statistical work. A review by the IMF found that the methods Alesina used in an attempt to identify examples of sharp austerity produced many misidentifications. For example, in 2000 Finland’s budget deficit dropped sharply thanks to a stock market boom, which caused a surge in government revenue – but Alesina mistakenly identified this as a major austerity programme. When the IMF laboriously put together a new database of austerity measures derived from actual changes in spending and tax rates, it found that austerity has a consistently negative effect on growth.

Yet even the IMF’s analysis fell short – as the institution itself eventually acknowledged. I’ve already explained why: most historical episodes of austerity took place under conditions very different from those confronting western economies in 2010. For example, when Canada began a major fiscal retrenchment in the mid-1990s, interest rates were high, so the Bank of Canada could offset fiscal austerity with sharp rate cuts – not a useful model of the likely results of austerity in economies where interest rates were already very low. In 2010 and 2011, IMF projections of the effects of austerity programmes assumed that those effects would be similar to the historical average. But a 2013 paper co-authored by the organisation’s chief economist concluded that under post-crisis conditions the true effect had turned out to be nearly three times as large as expected.

So much, then, for invisible bond vigilantes and faith in the confidence fairy. What about the backup bogeyman, the Reinhart-Rogoff claim that there was a red line for debt at 90% of GDP?

Well, in early 2013 researchers at the University of Massachusetts examined the data behind the Reinhart-Rogoff work. They found that the results were partly driven by a spreadsheet error. More important, the results weren’t at all robust: using standard statistical procedures rather than the rather odd approach Reinhart and Rogoff used, or adding a few more years of data, caused the 90% cliff to vanish. What was left was a modest negative correlation between debt and growth, and there was good reason to believe that in general slow growth causes high debt, not the other way around.

By about two years ago, then, the entire edifice of austerian economics had crumbled. Events had utterly failed to play out as the austerians predicted, while the academic research that allegedly supported the doctrine had withered under scrutiny. Hardly anyone has admitted being wrong – hardly anyone ever does, on any subject – but quite a few prominent austerians now deny having said what they did, in fact, say. The doctrine that ruled the world in 2010 has more or less vanished from the scene.

Except in Britain.

Chapter fourA distinctly British delusion

n the US, you no longer hear much from the deficit scolds who loomed so large in the national debate circa 2011. Some commentators and media organisations still try to make budget red ink an issue, but there’s a pleading, even whining, tone to their exhortations. The day of the austerians has come and gone.

n the US, you no longer hear much from the deficit scolds who loomed so large in the national debate circa 2011. Some commentators and media organisations still try to make budget red ink an issue, but there’s a pleading, even whining, tone to their exhortations. The day of the austerians has come and gone.

Yet Britain zigged just as the rest of us were zagging. By 2013, austerian doctrine was in ignominious retreat in most of the world – yet at that very moment much of the UK press was declaring that doctrine vindicated. “Osborne wins the battle on austerity,” the Financial Times announced in September 2013, and the sentiment was widely echoed. What was going on? You might think that British debate took a different turn because the British experience was out of line with developments elsewhere – in particular, that Britain’s return to economic growth in 2013 was somehow at odds with the predictions of standard economics. But you would be wrong.

Austerity in the UK

Cyclically adjusted primary balance, percent of GDP

Chart 3Source: IMF, OECD, and OBR

The key point to understand about fiscal policy under Cameron and Osborne is that British austerity, while very real and quite severe, was mostly imposed during the coalition’s first two years in power. Chart 3 shows estimates of our old friend the cyclically adjusted primary balance since 2009. I’ve included three sources – the IMF, the OECD, and Britain’s own Office of Budget Responsibility – just in case someone wants to argue that any one of these sources is biased. In fact, every one tells the same story: big spending cuts and a large tax rise between 2009 and 2011, not much change thereafter.

Given the fact that the coalition essentially stopped imposing new austerity measures after its first two years, there’s nothing at all surprising about seeing a revival of economic growth in 2013.

Look back at Chart 2, and specifically at what happened to countries that did little if any fiscal tightening. For the most part, their economies grew at between 2 and 4%. Well, Britain did almost no fiscal tightening in 2014, and grew 2.9%. In other words, it performed pretty much exactly as you should have expected. And the growth of recent years does nothing to change the fact that Britain paid a high price for the austerity of 2010-2012.

British economists have no doubt about the economic damage wrought by austerity. The Centre for Macroeconomics in London regularly surveys a panel of leading UK economists on a variety of questions. When it asked whether the coalition’s policies had promoted growth and employment, those disagreeing outnumbered those agreeing four to one. This isn’t quite the level of unanimity on fiscal policy one finds in the US, where a similar survey of economists found only 2% disagreed with the proposition that the Obama stimulus led to higher output and employment than would have prevailed otherwise, but it’s still an overwhelming consensus.

By this point, some readers will nonetheless be shaking their heads and declaring, “But the economy is booming, and you said that couldn’t happen under austerity.” But Keynesian logic says that a one-time tightening of fiscal policy will produce a one-time hit to the economy, not a permanent reduction in the growth rate. A return to growth after austerity has been put on hold is not at all surprising. As I pointed out recently: “If this counts as a policy success, why not try repeatedly hitting yourself in the face for a few minutes? After all, it will feel great when you stop.”

In that case, however, what’s with sophisticated media outlets such as the FT seeming to endorse this crude fallacy? Well, if you actually read that 2013 leader and many similar pieces, you discover that they are very carefully worded. The FT never said outright that the economic case for austerity had been vindicated. It only declared that Osborne had won the political battle, because the general public doesn’t understand all this business about front-loaded policies, or for that matter the difference between levels and growth rates. One might have expected the press to seek to remedy such confusions, rather than amplify them. But apparently not.

Which brings me, finally, to the role of interests in distorting economic debate.

As Oxford’s Simon Wren-Lewis noted, on the very same day that the Centre for Macroeconomics revealed that the great majority of British economists disagree with the proposition that austerity is good for growth, the Telegraph published on its front page a letter from 100 business leaders declaring the opposite. Why does big business love austerity and hate Keynesian economics? After all, you might expect corporate leaders to want policies that produce strong sales and hence strong profits.

I’ve already suggested one answer: scare talk about debt and deficits is often used as a cover for a very different agenda, namely an attempt to reduce the overall size of government and especially spending on social insurance. This has been transparently obvious in the United States, where many supposed deficit-reduction plans just happen to include sharp cuts in tax rates on corporations and the wealthy even as they take away healthcare and nutritional aid for the poor. But it’s also a fairly obvious motivation in the UK, if not so crudely expressed. The “primary purpose” of austerity, the Telegraph admitted in 2013, “is to shrink the size of government spending” – or, as Cameron put it in a speech later that year, to make the state “leaner ... not just now, but permanently”.

Beyond that lies a point made most strongly in the US by Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute: business interests dislike Keynesian economics because it threatens their political bargaining power. Business leaders love the idea that the health of the economy depends on confidence, which in turn – or so they argue – requires making them happy. In the US there were, until the recent takeoff in job growth, many speeches and opinion pieces arguing that President Obama’s anti-business rhetoric – which only existed in the right’s imagination, but never mind – was holding back recovery. The message was clear: don’t criticise big business, or the economy will suffer.

If the political opposition won’t challenge the coalition’s bad economics, who will?

But this kind of argument loses its force if one acknowledges that job creation can be achieved through deliberate policy, that deficit spending, not buttering up business leaders, is the way to revive a depressed economy. So business interests are strongly inclined to reject standard macroeconomics and insist that boosting confidence – which is to say, keeping them happy – is the only way to go.

Still, all these motivations are the same in the United States as they are in Britain. Why are the US’s austerians on the run, while Britain’s still rule the debate?

It has been astonishing, from a US perspective, to witness the limpness of Labour’s response to the austerity push. Britain’s opposition has been amazingly willing to accept claims that budget deficits are the biggest economic issue facing the nation, and has made hardly any effort to challenge the extremely dubious proposition that fiscal policy under Blair and Brown was deeply irresponsible – or even the nonsensical proposition that this supposed fiscal irresponsibility caused the crisis of 2008-2009.

Why this weakness? In part it may reflect the fact that the crisis occurred on Labour’s watch; American liberals should count themselves fortunate that Lehman Brothers didn’t fall a year later, with Democrats holding the White House. More broadly, the whole European centre-left seems stuck in a kind of reflexive cringe, unable to stand up for its own ideas. In this respect Britain seems much closer to Europe than it is to America.

The closest parallel I can give from my side of the Atlantic is the erstwhile weakness of Democrats on foreign policy – their apparent inability back in 2003 or so to take a stand against obviously terrible ideas like the invasion of Iraq. If the political opposition won’t challenge the coalition’s bad economics, who will?

You might be tempted to say that this is all water under the bridge, given that the coalition, whatever it may claim, effectively called a halt to fiscal tightening midway through its term. But this story isn’t over. Cameron is campaigning largely on a spurious claim to have “rescued” the British economy – and promising, if he stays in power, to continue making substantial cuts in the years ahead. Labour, sad to say, are echoing that position. So both major parties are in effect promising a new round of austerity that might well hold back a recovery that has, so far, come nowhere near to making up the ground lost during the recession and the initial phase of austerity.

For whatever the politics, the economics of austerity are no different in Britain from what they are in the rest of the advanced world. Harsh austerity in depressed economies isn’t necessary, and does major damage when it is imposed. That was true of Britain five years ago – and it’s still true today.

Thursday, 2 April 2015

Greek defiance mounts as Alexis Tsipras turns to Russia and China

Ambrose Evans Pritchard in The Telegraph

Two months of EU bluster and reproof have failed to cow Greece. It is becoming clear that Europe’s creditor powers have misjudged the nature of the Greek crisis and can no longer avoid facing the Morton’s Fork in front of them.

Any deal that goes far enough to assuage Greece’s justly-aggrieved people must automatically blow apart the austerity settlement already fraying in the rest of southern Europe. The necessary concessions would embolden populist defiance in Spain, Portugal and Italy, and bring German euroscepticism to the boil.

Emotional consent for monetary union is ebbing dangerously in Bavaria and most of eastern Germany, even if formulaic surveys do not fully catch the strength of the undercurrents.

This week's resignation of Bavarian MP Peter Gauweiler over Greece’s bail-out extension can, of course, be over-played. He has long been a foe of EMU. But his protest is unquestionably a warning shot for Angela Merkel's political family.

Mr Gauweiler was made vice-chairman of Bavaria's Social Christians (CSU) in 2013 for the express purpose of shoring up the party's eurosceptic wing and heading off threats from the anti-euro Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD).

Yet if the EMU powers persist mechanically with their stale demands - even reverting to terms that the previous pro-EMU government in Athens rejected in December - they risk setting off a political chain-reaction that can only eviscerate the EU Project as a motivating ideology in Europe.

Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission’s chief, understands the risk perfectly, warning anybody who will listen that Grexit would lead to an “irreparable loss of global prestige for the whole EU” and crystallize Europe’s final fall from grace.

When Warren Buffett suggests that Europe might emerge stronger after a salutary purge of its weak link in Greece, he confirms his own rule that you should never dabble in matters beyond your ken.

Alexis Tsipras leads the first radical-Leftist government elected in Europe since the Second World War. His Syriza movement is, in a sense, totemic for the European Left, even if sympathisers despair over its chaotic twists and turns. As such, it is a litmus test of whether progressives can pursue anything resembling an autonomous economic policy within EMU.

There are faint echoes of what happened to the elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, a litmus test for the Latin American Left in its day. His experiment in land reform was famously snuffed out by a CIA coup in 1954, with lasting consequences. It was the moment of epiphany for Che Guevara (below), then working as a volunteer doctor in the country.

A generation of students from Cuba to Argentina drew the conclusion that the US would never let the democratic Left hold power, and therefore that power must be seized by revolutionary force.

We live in gentler times today, yet any decision to eject Greece and its Syriza rebels from the euro by cutting off liquidity to the Greek banking system would amount to the same thing, since the EU authorities do not have a credible justification or a treaty basis for acting in such a way. Rebuking Syriza for lack of “reform” sticks in the craw, given the way the EU-IMF Troika winked at privatisation deals that violated the EU’s own competition rules, and chiefly enriched a politically-connected elite.

Forced Grexit would entrench a pervasive suspicion that EU bodies are ultimately agents of creditor enforcement. It would expose the Project’s post-war creed of solidarity as so much humbug.

Willem Buiter, Citigroup’s chief economist, warns that Greece faces an “economic show of horrors” if it returns to the drachma, but it will not be a pleasant affair for Europe either. “Monetary union is meant to be unbreakable and irrevocable. If it is broken, and if it is revoked, the question will arise over which country is next,” he said.

“People have tried to make Greece into a uniquely eccentric member of the eurozone, accusing them of not doing this or not doing that, but a number of countries share the same weaknesses. You think the Greek economy is far too closed? Welcome to Portugal. You think there is little social capital in Greece, and no trust between the government and citizens? Welcome to southern Europe,” he said.

Greece could not plausibly remain in Nato if ejected from EMU in acrimonious circumstances. It would drift into the Russian orbit, where Hungary’s Viktor Orban already lies. The southeastern flank of Europe’s security system would fall apart.

Rightly or wrongly, Mr Tsipras calculates that the EU powers cannot allow any of this to happen, and therefore that their bluff can be called. “We are seeking an honest compromise, but don't expect an unconditional agreement from us," he told the Greek parliament this week.

If it were not for the fact that a sovereign default on €330bn of debts – bail-out loans and Target2 liabilities within the ECB system – would hurt taxpayers in fellow Club Med states that are also in distress, most Syriza deputies would almost relish the chance to detonate this neutron bomb.

Mr Tsipras is now playing the Russian card with an icy ruthlessness, more or less threatening to veto fresh EU measures against the Kremlin as the old set expires. “We disagree with sanctions. The new European security architecture must include Russia,” he told the TASS news agency.

He offered to turn Greece into a strategic bridge, linking the two Orthodox nations. “Russian-Greek relations have very deep roots in history,” he said, hitting all the right notes before his trip to Moscow next week.

The Kremlin has its own troubles as Russian companies struggle to meet redemptions on $630bn of dollar debt, forcing them to seek help from state’s reserve funds. Russia’s foreign reserves are still $360bn – down from $498bn a year ago – but the disposable sum is far less given a raft of implicit commitments. Even so, President Vladimir Putin must be sorely tempted to take a strategic punt on Greece, given the prize at hand.

Panagiotis Lafazanis, Greece’s energy minister and head of Syriza’s Left Platform, was in Moscow this week meeting Gazprom officials. He voiced a “keen interest” in the Kremlin’s new pipeline plan though Turkey, known as "Turkish Stream".

Operating in parallel, Greece’s deputy premier, Yannis Drakasakis, vowed to throw open the Port of Piraeus to China’s shipping group Cosco, giving it priority in a joint-venture with the Greek state’s remaining 67pc stake in the ports. On cue, China has bought €100m of Greek T-bills, helping to plug a funding shortfall as the ECB orders Greek banks to step back.

One might righteously protest at what amounts to open blackmail by Mr Tsipras, deeming such conduct to be a primary violation of EU club rules. Yet this is to ignore what has been done to Greece over the past four years, and why the Greek people are so angry.

Leaked IMF minutes from 2010 confirm what Syriza has always argued: the country was already bankrupt and needed debt relief rather than new loans. This was overruled in order to save the euro and to save Europe’s banking system at a time when EMU had no defences against contagion.

Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras and finance minister Yanis Varoufakis

Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis rightly calls it “a cynical transfer of private losses from the banks’ books onto the shoulders of Greece’s most vulnerable citizens”. A small fraction of the €240bn of loans remained in the Greek economy. Some 90pc was rotated back to banks and financial creditors. The damage was compounded by austerity overkill. The economy contracted so violently that the debt-ratio rocketed instead of coming down, defeating the purpose.

India’s member on the IMF board warned that such policies could not work without offsetting monetary stimulus. "Even if, arguably, the programme is successfully implemented, it could trigger a deflationary spiral of falling prices, falling employment and falling fiscal revenues that could eventually undermine the programme itself.” He was right in every detail.

Marc Chandler, from Brown Brothers Harriman, says the liabilities incurred – pushing Greece’s debt to 180pc of GDP - almost fit the definition of “odious debt” under international law. “The Greek people have not been bailed out. The economy has contracted by a quarter. With deflation, nominal growth has collapsed and continues to contract,” he said.

The Greeks know this. They have been living it for five years, victims of the worst slump endured by any industrial state in 80 years, and worse than European states in the Great Depression. The EMU creditors have yet to acknowledge in any way that Greece was sacrificed to save monetary union in the white heat of the crisis, and therefore that it merits a special duty of care. Once you start to see events through Greek eyes – rather than through the eyes of the north European media and the Brussels press corps - the drama takes on a different character.

It is this clash of two entirely different and conflicting narratives that makes the crisis so intractable. Mr Tsipras told his own inner circle privately before his election in January that if pushed to the wall by the EMU creditor powers, he would tell them “to do their worst”, bringing the whole temple crashing down on their heads. Everything he has done since suggests that he may just mean it.

Tuesday, 31 March 2015

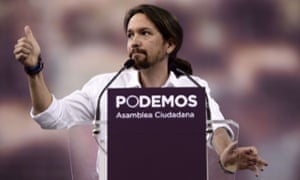

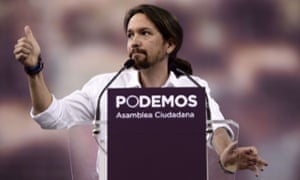

The Podemos revolution: how a small group of radical academics changed European politics

At the start of the 2008 academic year, Pablo Iglesias, a 29-year-old lecturer with a pierced eyebrow and a ponytail greeted his students at the political sciences faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid by inviting them to stand on their chairs. The idea was to re-enact a scene from the film Dead Poets Society. Iglesias’s message was simple. His students were there to study power, and the powerful can be challenged. This stunt was typical of him. Politics, Iglesias thought, was not just something to be studied. It was something you either did, or let others do to you. As a professor, he was smart, hyperactive and – as a founder of a university organisation called Counter-Power – quick to back student protest. He did not fit the classic profile of a doctrinaire intellectual from Spain’s communist-led left. But he was clear about what was to blame for the world’s ills: the unfettered, globalised capitalism that, in the wake of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, had installed itself as the developed world’s dominant ideology.

Iglesias and the students, ex-students and faculty academics worked hard to spread their ideas. They produced political television shows and collaborated with their Latin American heroes – left-leaning populist leaders such as Rafael Correa of Ecuador or Evo Morales of Bolivia. But when they launched their own political party on 17 January 2014 and gave it the name Podemos (“We Can”), many dismissed it. With no money, no structure and few concrete policies, it looked like just one of several angry, anti-austerity parties destined to fade away within months.

A year later, on 31 January 2015, Iglesias strode across a stage in Madrid’s emblematic central square, the Puerta del Sol. It was filled with 150,000 people, squeezed in so tightly that it was impossible to move. He addressed the crowd with the impassioned rhetoric for which opponents have branded him a dangerous leftwing populist. He railed against the monsters of “financial totalitarianism” who had humiliated them all. He told Podemos’s followers to dream and, like that noble madman Don Quixote, “take their dreams seriously”.Spain was in the grip of historic, convulsive change. The serried crowd were heirs to the common folk who – armed with knives, flowerpots and stones – had rebelled against Napoleonic troops in nearby streets two centuries earlier. “We can dream, we can win!” he shouted.

Polls suggest that he is right. Since 1982, Spain has been governed by only two parties. Yet El País newspaper now places Podemos at 22%, ahead of both the ruling conservative Partido Popular (PP) and its leftwing opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). If Podemos can grow further, Iglesias could become prime minister after elections that are expected in November. This would be an almost unheard-of achievement for such a young party.

Many in the Puerta del Sol longed to see that day. “Yes we can! Yes we can!” they chanted. Other onlookers shivered, recalling Iglesias’s praise for Venezuela’s late president Hugo Chávez and fearing an eruption of Latin American-style populism in a country gripped by debt, austerity and unemployment. But without Podemos, supporters feared, Spain faced the prospect of becoming like Greece, with its disintegrating welfare state, crumbling middle class and rampant inequality.

On stage that day, Iglesias declared that Podemos would take back power from self-serving elites and hand it over to the people. To do that, the new party needs votes. If that means arousing emotions and being accused of populism, so be it. And, as the party’s founders have already shown, if they have to renounce some of their ideas in order to broaden their appeal, or risk upsetting some in their grassroots movement by tightening central control, they are ready to do that, too. The aim, after all, is to win.

At first glance, Podemos’s dizzying rise looks miraculous. In truth, the project evolved over a long time, though even the organisers did not know it would eventually spawn a party, or that a global financial crisis would provide their opportunity. In Spain today, one-third of the labour force is either jobless or earns less than the minimum annual salary of €9,080. In big cities, the sight of people raiding bins for food or things to sell – a rarity in pre-crisis Spain – is no longer shocking. A fatalistic gloom has settled over a country that rode a wave of optimism for three decades after it transformed itself from dictatorship to democracy. After years of economic growth, the financial crisis burst Spain’s construction bubble. Countless corruption cases – involving both the PP and PSOE – have stoked widespread anger towards the established political class. “A political crisis is a moment for daring,” Iglesias told an audience recently. “It is when a revolutionary is capable of looking people in the eye and telling them, ‘Look, those people are your enemies.’”

He is not the first Pablo Iglesias to shake Spain’s political order. He is named after the man who founded the PSOE in 1879. (His parents first met at a remembrance ceremony in front of Iglesias’s tomb.) As a teenager, Iglesias was a member of the Communist Youth in Vallecas, one of Madrid’s poorest and proudest barrios. He still lives there today, in a modest apartment on a graffiti-daubed 1980s estate of medium- and high-rise blocks. (“Defend your happiness, organise your rage,” reads one graffiti slogan.) Even as a teenager, he was “a leader and great seducer”, recalled a senior Podemos member who had attended the same youth group. Iglesias studied law at the Complutense University before taking a second undergraduate degree in political science. He went on to write a PhD thesis on disobedience and anti-globalisation protests that was awarded a prestigious cum laude grade

.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Demonstrators gather near Madrid’s Puerta del Sol for a ‘March for Change’ organised by Podemos in January. Photograph: Gerard Julien/AFP/Getty

Somehow a protest march had turned into a camp that eventually drew tens of thousands of protesters. The indignados, who would inspire the Occupy movement, then took over city squares across the country, railing against politicians. “They don’t represent us!” became the rallying cry. Polls showed that 80% of the public backed the protestors. Some even carried Spain’s red-and-gold flag, a sign that this was bigger than the standard leftwing protests at which the purple, gold and red flag of Spain’s long-lost Republic usually dominated. The indignados debated at open-air assemblies, taking turns to speak and using hand gestures – raised waving hands for “yes”, crossed arms for “no” – to express agreement or disagreement.

For Iglesias and his fellow theorists at Complutense University, the protests made perfect sense. The consensus between Spain’s two biggest parties around German-imposed austerity had turned many citizens into political orphans, with no one to represent them. “Those with the power still governed, but they no longer convinced people,” Errejón told me recently.

Still, a month after the protests began, the squares had emptied. Six months later, at the end of 2011, Spain elected a new government, amid warnings that, whoever won, German chancellor Angela Merkel would be in charge. Disillusioned voters saw that even the PSOE offered little more than cowed obedience to Merkel’s demands for more austerity. Following a low turnout, Mariano Rajoy’s PP won an absolute majority and introduced further cuts while slowly taming budget deficits that had topped 11%. The indignado spirit, it seemed, had been crushed.

In fact, indignado assemblies continued to meet, and for the most politically active, La Tuerka became essential viewing. With time, the show moved to the online news site Público, and became more polished. Each show would begin with Iglesias or his fellow Complutense professor Juan Carlos Monedero delivering a monologue, followed by debate and rap music. When Iran’s state-run Spanish-language television service, HispanTV, asked for an Iglesias-presented show, starting in January 2013, the team jumped at it. The show, called Fort Apache, opened with Iglesias astride a Harley Davidson Sportster motorbike, placing a helmet over his head and – after a close-up of his eyes – slinging a massive crossbow across his back before roaring off. “Watch your head, white man. This is Fort Apache!” he warned in the trailers. They were still, however, preaching mostly to a small number of the already converted.

All that changed on 25 April 2013, when Iglesias appeared on a rightwing debate show on the small channel Intereconomia. “It is a pleasure to cross enemy lines and talk,” said Iglesias by way of introduction. He was outnumbered. He would be debating against four conservative pundits. But Iglesias had come prepared and acquitted himself well. Soon, he was receiving invitations to appear on debate shows on Spain’s mainstream channels. Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and a series of simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters. The cocksure young lecturer usually sat with one ankle resting on a knee and an arm casually thrown behind his chair, his smile occasionally slipping into condescension. He repeated, mantra-like, that the blame for Spain’s woes lay with “la casta”, his name for the corrupt political and business elites he claimed had sold the country to the banks. The other enemy was Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel and the unelected officials who oversaw the euro from the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. Iglesias did not want Spain to leave the European Union, but he was not satisfied with it either. Above all, he wanted Spaniards to recover “sovereignty”, a concept that, like many others, remained fuzzy.

Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters

A media star had been born. Many knew him just as “el coletas” (“the pony-tailed one”). Iglesias had spent years honing his technique, doing theatre and even attending a presenter’s course at state television RTVE’s academy. Communication, he had already declared in his PhD thesis, was key to protest. For years he and Monedero had been telling Spain’s communist-led leftwing coalition Izquierda Unida (IU) that it should learn from the Latin Americans and widen its appeal. Now they proposed a broad leftwing movement, with open primaries at which outside candidates such as Iglesias could stand. They received a firm no from IU leader Cayo Lara, who later declared that Iglesias had “the principles of Groucho Marx”. So they created it themselves.

* * *

The Podemos plan was cemented over a dinner in August 2013, during the four-day “summer university” of a tiny, radical party called Izquierda Anticapitalista (IA). Iglesias and IA heavyweight Miguel Urbán, then a then 33-year-old veteran of multiple protest movements agreed to work together, creating the strange and tense marriage between a single, charismatic leader – Iglesias – and an organisation that hates hierachy. “Pablo had political and media prestige, but that was not enough,” Urbán told me. “We needed an organisational base that stretched across the country, and that was IA.”

The plan was daring and highly improbable. It was to be an 18-month assault on power, with the ultimate aim being to replace the PSOE as leaders of the left and unseat Prime Minister Rajoy at the 2015 general election. The core clique of like-minded academics from the Complutense political sciences faculty, who were veterans of La Tuerka, would manage the campaign. At last, they would be able to try out their ideas on a national scale.

The first test for Podemos would be the May 2014 European elections. Many voters view the European parliament as toothless because the EU’s major decisions are taken elsewhere. With so little at stake, they take risks in the polling booth. Iglesias and Urbán saw the European elections as a potential springboard for their 2015 general election campaign. The party’s name – which echoes not just Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign slogan, but also a TV jingle for Spain’s European and World Cup-winning football team – came during a car journey a few months after the forming of the initial pact between Iglesias and Urbán. “We thought of ‘Yes you can!’, but that already existed,” said Urbán. “So then we went for Podemos [We Can]. It was nicely affirmative.”

On January 17 2014, Iglesias officially announced the creation of Podemos at a small theatre in Lavapiés, the hip Madrid district that over the past decade has filled up with alternative bookshops, galleries and bars. Iglesias (his eyebrow stud now removed in order to improve his electoral image) explained that a cornerstone of the Podemos project would be indignado-style “circles”, or assemblies. These circles, built around local communities or shared political interests, could meet, debate or vote in person or online. He told the crowd that if 50,000 people signed a petition on the Podemos website, he would lead a list of candidates at the European parliamentary elections in May. The target was reached within 24 hours, despite the website crashing for part of that time.

Pablo Echenique got involved with Podemos via its regional ‘circles’, and was elected as an MEP in 2014. Photograph: Jose Luis Cuesta/Cordon Press/Corbis

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.

Pablo Echenique, a research physicist with spinal muscular atrophy, saw the Lavapiés speech on YouTube at his home in Zaragoza, central Spain. Three years earlier, Echenique had bumped along Zaragoza’s streets in his electric wheelchair to join the indignado protesters. He was excited by the debates, but frustrated by the lack of action. “They had no bite,” he told me. “There was no answer about what to do next.” When, four days after the Lavapiés speech, Iglesias travelled to a cultural centre beside Plaza San Agustín in Zaragoza for his first European election campaign meeting , Echenique got there early, but the 180-seat hall filled quickly. “Soon there were 500 people outside, so Pablo said: ‘I know it’s cold, but it’s worse not to have a job. We don’t fit here, so let’s go out into the plaza.’ It was freezing.”

It was in Zaragoza that Urbán first realised that Podemos might succeed. “As I waited at the door, someone asked whether I was from Podemos in Zaragoza,” Urbán told me. “I was in charge of Podemos’s organisation, but thought we didn’t really exist yet, so I just said I had come from Madrid. He replied, ‘Well, I’m from Podemos in Calatayud.’ That’s a town with just 20,000 inhabitants. Suddenly I realised that something really had changed. It was the political equivalent of occupying the squares.” A pattern was set, of packed campaign meetings that were generally ignored by the press. For those involved, it was exhilarating. Urbán took home the money gathered at the meetings to count. “We would get €2,000 from a single meeting. It was like belonging to a church,” he said.

Iglesias said politics was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience

Echenique was inspired. “I told Pablo, ‘You say we should get organised, but I’ve never been in an organised political party. Can you give me some ideas?’ Pablo said it was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience.” Echenique joined two circles, one in Zaragoza and one online-based group for people with disabilities. He was one of 150 candidates put forward by circles for the European parliament. These were ranked in order by 33,000 people who signed on for free to the party website. Iglesias came first and Echenique was fifth. Only one of the top 12 candidates was over 36 years old.

Podemos then embarked on the complex process of writing a “participative” election manifesto, based on ideas from the circles and then voted for online. The result was original, but also impractical and uncosted. It called for a basic state salary for all citizens and non-payment of “illegitimate” parts of the public debt, although the manifesto did not specify which parts these were – two measures that Podemos has since back-pedalled on.

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.

Pablo Echenique, a research physicist with spinal muscular atrophy, saw the Lavapiés speech on YouTube at his home in Zaragoza, central Spain. Three years earlier, Echenique had bumped along Zaragoza’s streets in his electric wheelchair to join the indignado protesters. He was excited by the debates, but frustrated by the lack of action. “They had no bite,” he told me. “There was no answer about what to do next.” When, four days after the Lavapiés speech, Iglesias travelled to a cultural centre beside Plaza San Agustín in Zaragoza for his first European election campaign meeting , Echenique got there early, but the 180-seat hall filled quickly. “Soon there were 500 people outside, so Pablo said: ‘I know it’s cold, but it’s worse not to have a job. We don’t fit here, so let’s go out into the plaza.’ It was freezing.”

It was in Zaragoza that Urbán first realised that Podemos might succeed. “As I waited at the door, someone asked whether I was from Podemos in Zaragoza,” Urbán told me. “I was in charge of Podemos’s organisation, but thought we didn’t really exist yet, so I just said I had come from Madrid. He replied, ‘Well, I’m from Podemos in Calatayud.’ That’s a town with just 20,000 inhabitants. Suddenly I realised that something really had changed. It was the political equivalent of occupying the squares.” A pattern was set, of packed campaign meetings that were generally ignored by the press. For those involved, it was exhilarating. Urbán took home the money gathered at the meetings to count. “We would get €2,000 from a single meeting. It was like belonging to a church,” he said.

Iglesias said politics was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience

Echenique was inspired. “I told Pablo, ‘You say we should get organised, but I’ve never been in an organised political party. Can you give me some ideas?’ Pablo said it was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience.” Echenique joined two circles, one in Zaragoza and one online-based group for people with disabilities. He was one of 150 candidates put forward by circles for the European parliament. These were ranked in order by 33,000 people who signed on for free to the party website. Iglesias came first and Echenique was fifth. Only one of the top 12 candidates was over 36 years old.

Podemos then embarked on the complex process of writing a “participative” election manifesto, based on ideas from the circles and then voted for online. The result was original, but also impractical and uncosted. It called for a basic state salary for all citizens and non-payment of “illegitimate” parts of the public debt, although the manifesto did not specify which parts these were – two measures that Podemos has since back-pedalled on.

.

Alexis Tsipras (left), leader of Greece’s Syriza party and now the country’s prime minister, with Podemos leader Igelsias. Photograph: Lefteris Pitarakis/AP

Little more than a month before the European elections, Podemos’s own polling revealed that only 8% of Spaniards had heard of them. However, 50% knew who Pablo Iglesias was. The party took the controversial step of changing its logo, putting Iglesias’s face on it to ensure it would go on the ballot slips. Eighteen days before the vote, the state-run pollster CIS said Podemos might scrape one seat.

On the night of the election, Podemos surprised everybody. It took 8% of the vote, with Iglesias, Echenique and three others becoming MEPs. Amid all the celebration, Iglesias remained cool. The PP was still in government, he warned. The battle had only just begun.

* * *

Eight months after the elections, on a flight back to Madrid from Athens in January, Iglesias sat, as he always does, in a budget seat. He had just helped Alexis Tsipras of Syriza close a campaign rally with a line by Leonard Cohen – “First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin” – and a few well-pronounced words in Greek. It was an early start after a late night, but he was already in work mode. “I drink Red Bull so that I can read on long flights,” he said in the lounge, as a Greek businessman who owned restaurants in Madrid insisted on paying for our cafe freddo at the coffee kiosk and enthused about the changes coming to both countries.

In person, Iglesias’s combative public persona gives way to careful politeness (“Like the perfect son-in-law,” according to Mouffe). Unlike other leading politicians, he refuses to ride around in official cars, but he has lost his freedom to walk down the street or go into a bar without being stopped. When we arrived at Madrid’s Barajas airport, a lottery ticket vendor who caught sight of him stopped in her tracks. “You don’t have to buy. Just win!” she said, eyes bulging.

Iglesias was energised by his Athens visit, but Tsipras had been less effusive the night before, when, at a party on the terrace of a nightclub with spectacular views of the Parthenon, I asked him whether a future Podemos victory was key toSyriza. Not really, he answered. “Their elections are not for a while,” said the man who, three days later, became Europe’s lone austerity rebel. “I think we will open roads for them.”

Spain is not Greece. Austerity may be hurting – the Roman Catholic charity Caritas distributed food, clothes and help to 2.5 million people (one in 20 Spaniards) last year – but it has not produced the scenes of deprivation that one regularly sees on the streets of Athens, such as the queues at charity pharmacies where those excluded from state medical care go for medicines. Still, “if this can happen to us,” said Iliopoulou Vassiliki, a pharmacy volunteer, expressing a fear shared by many Podemos supporters, “who will be next?”

A few days after Iglesias returned from Athens, Iglesias visited Valencia for a rally. Podemos will win much of the youth vote at the general election, but those who attend their rallies – many of them members of local Podemos circles – are mostly older. Activism comes more easily to those in their forties and above, many of whom recall the heady early years of Spain’s democratic transition and are surprised by the younger generation’s passivity. Loudspeakers pumped out Patti Smith’s People Have the Power to 8,000 people packed into the basketball stadium. “Here comes the rockstar moment,” warned a Spanish journalist as Iglesias and Errejón appeared to raucous applause. A middle-aged woman in leopardskin-print trousers bellowed: “Presidente! Presidente!” Someone else shouted: “Long live the mother who gave birth to you!”

As capital of a region notorious for political corruption, Valencia is fertile ground for Podemos. Iglesias read out a letter from Nerea, a girl who was there on her ninth birthday. “We like you because you help people,” it said. “Thank you for giving my parents hope again.” The father held the girl above his head. “They [the establishment] aren’t afraid of me, Nerea. They are afraid of you and families who have said, ‘That’s enough!’,” said Iglesias, before segueing into a series of slogans: “The smiles have changed sides”; “Of course we can!” John Carlin, an El País writer, says Iglesias is selling a religious tale similar to that of Jesus expelling the money changers. The implication is that Podemos’s followers prefer the uplifting feeling of shared faith to cool reason. I recalled a volunteer in a Podemos office in Madrid who surprised me by confiding that he would not vote for them. “There is too much emotion,” he said.

Podemos activist Irene Camps had come to the rally with circle members from Manises, a struggling industrial town near Valencia’s airport where a former PP mayor is being tried for (which he denies). One evening a few weeks after the rally, Camps and I stood outside the local Consum supermarket with half a dozen women who were waiting to go through its bins for food. Nearby, a huge theatre, the construction of which started during Spain’s boom days before the 2007 crash, sat unfinished. “Everyone’s talking about Podemos. We should give them a chance,” said Paqui Fernández, the women’s self-appointed leader. She and her friends recalled that this land was occupied by “cave-houses” – homes built from holes in the rock – in the 1950s. It was a reminder of how far Spain has come since the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, but also that memories of poverty are not that old. Camps is part of Spain’s recently expanded, but now shrinking and scared, middle class. “If we don’t change things,” she said. “I’ll end up like Paqui.”

The party’s use of transparency websites, voting tools and online debate is already cutting-edge

The next day, bathed in winter sunshine, Camps helped at an open-air Podemos assembly on a ramshackle estate of detached houses in countryside outside Manises. Timid locals stepped into a circle of earnest, purple-shirted activists and were applauded for airing their fears. The party’s 900-odd circles are key to Podemos’s participative approach and local popularity, but they are hard to control. (The party still does not have a full list of them.) Anyone can join in and vote.