Will Hutton in The Guardian

July 1909: a street in Bournville village near Birmingham, a new town founded by chocolate manufacturer and social reformer George Cadbury. Photograph: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

More than 100 years ago, the Cadbury family built a model town, Bournville, for their workers, away from the overcrowded tenements of central Birmingham. Cadbury’s vast chocolate factory was at the centre of thousands of purpose-built villas, a village green, schools, churches and civic halls.

The message was clear. Cadbury cherished and invested in their workers, expecting commitment and loyalty back, which they got. Sir Adrian Cadbury, now in his 80s, still proudly shows visitors how his Quaker forefathers felt a genuine sense of responsibility to their workers. His family believed in capitalism for a purpose – innovation and human betterment.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, would regard the Cadbury family as crazed. His relationship with his workforce is entirely transactional: they are to give their heart and soul to Amazon, undertaking to follow Amazon’s “leadership principles”, set on a laminated card given to every employee, and can expect to be summarily sacked if they don’t make the grade. These injunctions are aimed at not only Amazon’s fork-lift truck drivers and packagers but also at its executive workforce.

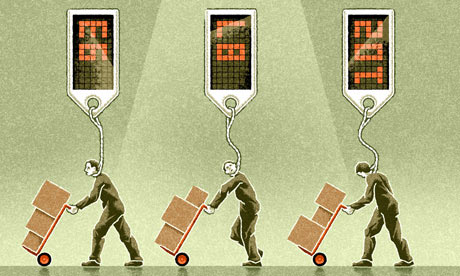

At first glance, the principles seem unexceptional, exhorting “ Amazonians” to be obsessed with customers, drive for the best and think big. In practice, they mean workers have to be available to Amazon virtually every waking hour, as a devastating article claimed in last week’s New York Times. The workers should attack each other’s ideas in the name of “creative challenge” and buy into the paranoid culture Bezos believes is essential to business success, with their hourly performance fed into computers for Big Brother Bezos to monitor.

Working at Amazon has become synonymous with stress, conflict and tears – or, if you swim rather than sink, a chance to flourish. It is, as one former executive described it, “purposeful Darwinism”: if the majority of the workforce can flourish in such a culture, you have a successful company. Bezos would claim in his defence that he has founded the US’s most valuable retailer that ships two billion items a year. Cadbury ended up being taken over. Better his approach to capitalism than defunct Quakers, except now everyone is expendable. This is the route to success. Or is it?

The nature of firms is changing. The capitalist world of the so-called golden age between 1945 and the first oil crisis in 1974 was defined by Cadbury-type companies. Even if they didn’t build estates in which their workers could live, big companies offered paid holidays, guaranteed pensions related to your final salary, sickness benefit and recognised trade unions. Above all, they offered the chance of a career and personal progression.

This was the domain of the corporation man commuting to a steady job in a steady office in a steady company with their blue-collar counterparts no less secure in a steady factor. It delivered though. If western economies could again grow consistently at 3% or 4%, underpinned by matching growth in productivity, there would be delight all round.

The companies were much more exciting than they looked. They were purposeful – repositories of skills and knowledge, seeking out new markets, applying new technologies with an appetite for growth. In Britain, great companies such as ICI, Glaxo, EMI, Unilever, Thorn, British Aircraft Corporation, Marconi along with Cadbury were centres of growth and innovation.

A critical doctrine at the time was they were held back by trade unions and soft economic policy that encouraged inflation. The proof that inflation was so damaging is scant and beyond the print, coal, rail and motor industries, British trade unions were pretty weak and pliant. What instead held these companies back was the evaporation of the guaranteed markets of empire. Second, a short-term, gentlemanly, disengaged financial system was unable to mobilise resource behind these companies and their greater purpose as imperial markets shrank. That wasn’t widely understood then – and certainly not now. Instead, the economic problem was defined as pampered, unionised workers, a view further entrenched by an avalanche of free-market economics from the US. Worker privileges and rights must cease.

So to the firm of today. The new model firm no longer has workers who are members of the organisation in a relationship of mutual respect and shared mission with committed, long-term owners; rather, the new ownerless corporation with its tourist shareholders employs contractors who have to pay for benefits themselves and can be hired and fired at will.

They are throwaway people, middle-class workers at risk as much as their working-class peers. Unions are not welcome; pension benefits are scaled back; sickness, paternity and maternity benefits are pitched at the regulatory minimum. Last week, the Citizens Advice Bureau said it estimated that 460,000 people nationwide had been defined by employers as self-employed (and thus entitled to no company benefits), even though they worked regularly for one employer, often in office roles. It is the same approach that has delivered 1.4 million zero-hours contracts. All this allegedly is to serve growth. Except over the last 20 years, growth, productivity and innovation in both Britain and America have collapsed. These new firms whose only purpose is short-term profit with contractualised workforces turn out to be poor creators of long-term value. The exceptions, paradoxically, are the great hi-tech companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook.

The alchemy of their success is they combine innovative technology, produce at continental scale, invest heavily and commit to a great purpose, usually because of the powerful personal commitment of the founder. Bezos may have constructed a Darwinian work environment but it is all “to be the Earth’s most customer-centric company”. He has invested hugely to achieve that end, but his workplaces, by contrast, seem terrible.

But even Bezos does not want to be depicted as an employer with no moral centre: he urged his employees to read the offending article and refer examples of bad practice to his human resources department.

Ultimately, long-term value creation can’t be done by treating your workforces as cattle. It’s the great debate about today’s capitalism. It would be a triumph if it was taken more seriously in Britain.

More than 100 years ago, the Cadbury family built a model town, Bournville, for their workers, away from the overcrowded tenements of central Birmingham. Cadbury’s vast chocolate factory was at the centre of thousands of purpose-built villas, a village green, schools, churches and civic halls.

The message was clear. Cadbury cherished and invested in their workers, expecting commitment and loyalty back, which they got. Sir Adrian Cadbury, now in his 80s, still proudly shows visitors how his Quaker forefathers felt a genuine sense of responsibility to their workers. His family believed in capitalism for a purpose – innovation and human betterment.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, would regard the Cadbury family as crazed. His relationship with his workforce is entirely transactional: they are to give their heart and soul to Amazon, undertaking to follow Amazon’s “leadership principles”, set on a laminated card given to every employee, and can expect to be summarily sacked if they don’t make the grade. These injunctions are aimed at not only Amazon’s fork-lift truck drivers and packagers but also at its executive workforce.

At first glance, the principles seem unexceptional, exhorting “ Amazonians” to be obsessed with customers, drive for the best and think big. In practice, they mean workers have to be available to Amazon virtually every waking hour, as a devastating article claimed in last week’s New York Times. The workers should attack each other’s ideas in the name of “creative challenge” and buy into the paranoid culture Bezos believes is essential to business success, with their hourly performance fed into computers for Big Brother Bezos to monitor.

Working at Amazon has become synonymous with stress, conflict and tears – or, if you swim rather than sink, a chance to flourish. It is, as one former executive described it, “purposeful Darwinism”: if the majority of the workforce can flourish in such a culture, you have a successful company. Bezos would claim in his defence that he has founded the US’s most valuable retailer that ships two billion items a year. Cadbury ended up being taken over. Better his approach to capitalism than defunct Quakers, except now everyone is expendable. This is the route to success. Or is it?

The nature of firms is changing. The capitalist world of the so-called golden age between 1945 and the first oil crisis in 1974 was defined by Cadbury-type companies. Even if they didn’t build estates in which their workers could live, big companies offered paid holidays, guaranteed pensions related to your final salary, sickness benefit and recognised trade unions. Above all, they offered the chance of a career and personal progression.

This was the domain of the corporation man commuting to a steady job in a steady office in a steady company with their blue-collar counterparts no less secure in a steady factor. It delivered though. If western economies could again grow consistently at 3% or 4%, underpinned by matching growth in productivity, there would be delight all round.

The companies were much more exciting than they looked. They were purposeful – repositories of skills and knowledge, seeking out new markets, applying new technologies with an appetite for growth. In Britain, great companies such as ICI, Glaxo, EMI, Unilever, Thorn, British Aircraft Corporation, Marconi along with Cadbury were centres of growth and innovation.

A critical doctrine at the time was they were held back by trade unions and soft economic policy that encouraged inflation. The proof that inflation was so damaging is scant and beyond the print, coal, rail and motor industries, British trade unions were pretty weak and pliant. What instead held these companies back was the evaporation of the guaranteed markets of empire. Second, a short-term, gentlemanly, disengaged financial system was unable to mobilise resource behind these companies and their greater purpose as imperial markets shrank. That wasn’t widely understood then – and certainly not now. Instead, the economic problem was defined as pampered, unionised workers, a view further entrenched by an avalanche of free-market economics from the US. Worker privileges and rights must cease.

So to the firm of today. The new model firm no longer has workers who are members of the organisation in a relationship of mutual respect and shared mission with committed, long-term owners; rather, the new ownerless corporation with its tourist shareholders employs contractors who have to pay for benefits themselves and can be hired and fired at will.

They are throwaway people, middle-class workers at risk as much as their working-class peers. Unions are not welcome; pension benefits are scaled back; sickness, paternity and maternity benefits are pitched at the regulatory minimum. Last week, the Citizens Advice Bureau said it estimated that 460,000 people nationwide had been defined by employers as self-employed (and thus entitled to no company benefits), even though they worked regularly for one employer, often in office roles. It is the same approach that has delivered 1.4 million zero-hours contracts. All this allegedly is to serve growth. Except over the last 20 years, growth, productivity and innovation in both Britain and America have collapsed. These new firms whose only purpose is short-term profit with contractualised workforces turn out to be poor creators of long-term value. The exceptions, paradoxically, are the great hi-tech companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook.

The alchemy of their success is they combine innovative technology, produce at continental scale, invest heavily and commit to a great purpose, usually because of the powerful personal commitment of the founder. Bezos may have constructed a Darwinian work environment but it is all “to be the Earth’s most customer-centric company”. He has invested hugely to achieve that end, but his workplaces, by contrast, seem terrible.

But even Bezos does not want to be depicted as an employer with no moral centre: he urged his employees to read the offending article and refer examples of bad practice to his human resources department.

Ultimately, long-term value creation can’t be done by treating your workforces as cattle. It’s the great debate about today’s capitalism. It would be a triumph if it was taken more seriously in Britain.

RJ Ellory admitted to using false names on Amazon to attack rivals (Picture: REX FEATURES)

RJ Ellory admitted to using false names on Amazon to attack rivals (Picture: REX FEATURES) Authors Ian Rankin, Lee Child and Val McDermid (Pictures: CHRIS WATT/GEOFF PUGH/GETTY IMAGES)

Authors Ian Rankin, Lee Child and Val McDermid (Pictures: CHRIS WATT/GEOFF PUGH/GETTY IMAGES) Mark Billingham was among those authors targeted by Ellory (Picture: GERAINT LEWIS)

Mark Billingham was among those authors targeted by Ellory (Picture: GERAINT LEWIS) Ellory was "unavailable" for further comment (Picture: GETTY IMAGES)

Ellory was "unavailable" for further comment (Picture: GETTY IMAGES)