Increasingly, corporations and politicians treat the poor with distrust. That's why this week's ruling on workfare was important

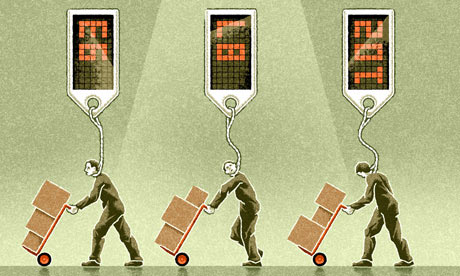

‘In the ruling in favour of Cait Reilly and Jamieson Wilson the judges were clear: these people were treated dishonestly.' Illustration by Matt Kenyon

Inside Amazon's flagship factory in Rugeley, Staffordshire, a new way of working is evolving. There is a strong topnote of distrust, evinced by the full-body scanners that workers have to pass, every time they leave, to prove they haven't stolen anything. The profound insecurity built into the employment model is dressed up as discipline – which is to say, Amazon expects huge seasonal fluctuations in the number of people it needs, yet likes to mask their dismissals behind a misdeameanour, so a lot of people get axed for crimes like being ill. There's a lifesized blonde lady made of cardboard at the entrance, with a think bubble coming out of her head that says, "This is the best job I've ever had!" If that detail alone is enough to make your blood run cold, marry it to the testimony of the chairman of nearby Lea Hall Miners Welfare Centre and Social Club: "The feedback we're getting is that it's like being in a slave camp."

Of all the details revealed by the Financial Times, the one that sank my spirits was the electronic tagging – workers have a handheld device directing them to goods. But these devices also measure their productivity in real time. If they lag behind, the machine bugs them. They are issued with constant warnings not to talk to one another or tarry for any reason. A lot of people find it quite stressful. Call them crazy. (Amazon counters: "Like most companies, we have performance expectations for every Amazon employee, and we measure actual performance against those expectations.")

Meanwhile, in Tesco's Donabate distribution centre in Dublin, workers wearing these tags are awarded percentages for their speediness (100% if they perform a task in the time estimated, 200% if they're twice as fast, and so on), but claim they are docked if they take a loo break; afterwards, they find they have to work much faster – to get back up to their 100%. To put it in context, workers routinely scoring 110% are reported to be sweating quite hard for most of the day. So making up your targets is no walk in the park. Tesco insists that their tag is turned off while workers are in the toilet.

Anybody who's ever worked in a very repetitive, menial job will recognise this suspicious atmosphere – the less enjoyable a job is, the more people there are who suspect you of trying to get out of it. That's reasonable, I suppose, though if people were treated less like robots to begin with, they might not need so much surveillance. But the fabled "innovation" of the private sector never seems to be able to extend itself towards making jobs more self-determining and satisfying. Presumably this is because there's always a danger that self-determining, satisfied people might distinguish themselves in some way, might cease to be interchangeable and might want – indeed, deserve – more than the paltry wage they might be being paid.

But there is innovation here, in a new shamelessness. Let's be honest, tagging is what you do to criminals. Criminals often don't mind this, because the alternative for them is prison. The understanding, however, is that there's already been a significant breakdown of respect between the authority and the person before anybody's movements are electronically monitored. It used to be taken as read that you wouldn't do that to a person until you already had good reason to suspect that they wouldn't tell you the truth.

I am reminded here of the Conservative MP Alec Shelbrooke calling for people's benefits to be delivered on a card, rather than cash, for the easier prohibition of the purchase of booze, fags, Sky+ and trips to Tenerife. Again, the government has form with this idea –certain categories of asylum seeker are given their sustenance on a card, with which they are banned from buying condoms and (obscurely) sanitary products.

A friend of mine stood behind an asylum seeker once while she was turned down for the purchase of some crayons. It's not a system I'd want on my conscience, but its development has some deterrence rationale to it: that is, to make conditions so unpleasant that the bogus claimant gives up of his or her own accord. So when did that become OK – to exclude benefit claimants from the mainstream economy, to humiliate them? Does Shelbrooke hope to deter them all from living here? Where does he propose they go?

What I cannot help noticing is a failure of normal human respect for the people at the bottom of the heap – Tuesday's ruling in favour of Cait Reilly and Jamieson Wilson has had its bones picked over for what it does or doesn't say about slavery, and yet the judges were clear: these people were treated dishonestly. They were treated as though, being unemployed, they could be parcelled about at the whim of the secretary of state.

A similar belief pervades the suggestion that those on benefits need to be ritually humiliated every time they go into a shop; or those on low wages, by dint of their low status, need to be monitored like criminals. Across the piece, having a low financial status is now elided, by politicians and by corporations, with being untrustworthy.

They may have different motives; Shelbrooke is hoping to make political capital out of the contempt in which he holds the poor; Tesco and Amazon's contempt is just a byproduct of their drive for profit. But the wellspring doesn't matter; what matters is that this is a frighteningly divisive worldview.

No comments:

Post a Comment