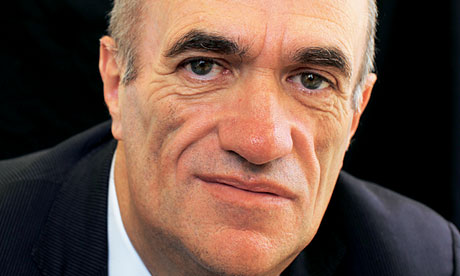

Financial analyst Neeraj Monga

Financial analyst Neeraj Monga’s reports have India Inc in a funk

The Canadian newspaper report, boldly headlined ‘Yellow Pages strikes back at analyst’, is framed and prominently displayed in a corner office of the Toronto-based firm Veritas Investment Research. The Financial Post article refers to a July 2006 report from Veritas, titled ‘The Count of Yellow Pages’, that was quite unambiguously bearish on the Yellow Pages Income Fund, even though at the time it was the second largest trust in Canada with a market capitalisation of over $8 billion. That didn’t prevent Veritas analysts Neeraj Monga and Chris Silvestre from arguing that “past performance is no indicator of future results. We believe that ypg is the poster child of this adage”.

|

The Bull Buster Age 40 Place of Birth Udaipur Work Executive vice-president and head of research at Toronto-based forensic accounting firm, Veritas, whose candid reports on prominent Indian firms are making headlines. Hobbies Monga enjoys cooking, especially experimenting with recipes. He likes Bollywood films (Dil Chahta Hai is a favourite) and listens to old Hindi music (especially Mohd Rafi). Has most recently read the biography of Steve Jobs. Loves travelling to sunnier climes. Family Wife Dimple is a homemaker. Children: Sanjana, 5, and Arjun, 1. |

In the Financial Post article, Yellow Pages CEO Marc Tellier had fired back that 11 of 12 analysts had “buy” recommendations on the company. Now, almost six years later, the stock which was then trading at nearly $16 barely touches double digits—in pennies—on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

India-born Monga, executive vice-president and head of research at Veritas, has written a bunch of reports since then, and those involved in the inner machinery of BSE 100 stocks will certainly be paying serious attention to his work. After all, his reports on Reliance Industries and Reliance Communications (exactly five years from the day the Yellow Pages report was published), and then on UB Holdings and Kingfisher Airlines and, most recently, on DLF, have generated tremors—and headlines.

As Monga points out in an interview at his Toronto office, this isn’t about ulterior motives and targeting Indian companies: “Ultimately, it’s about two things, governance and vision. There are very few visionary people out there, mostly in North America, creating businesses from scratch. In India, some of the biggest companies are trying to rip other people off.” That’s just the sort of candid language that has roiled the usually placid waters of equity research aimed at Indian corporates. For instance, the DLF report summarised: “If your investment decision incorporates management integrity, then bypassing DLF will be an easy choice.”

There’s more to come: Veritas established a research unit focused on India this January. Led by Monga, the unit expects to deliver between 6-8 reports in 2012 itself. As a frequent visitor to India, Monga is aware of the terrain: “India, in general, as a nation, has been led by rhetoric rather than fact. So I decided perhaps we can inject some facts into the debate.” Clearly, he has forceful views and is unafraid about presenting them. “Generally information coming out of India and/or China has been pretty...” Monga pauses and contemplates the apt word, “untrustworthy.”

|

‘Brothers In Arms’: Jul ’11 What Veritas said “We find no credible evidence of ‘values’ and ‘integrity’ in RCom’s financial statements or those of its former parent, RIL.”  RCom’s response “A malicious and motivated report containing baseless allegations, masquerading as research.” |

Monga’s Indian critics may well blame his father for preventing the son from taking on a career as the local cable guy, possibly in West Delhi’s Vikaspuri. His sister Parul, who works in Toronto as a trader with the Western Ontario Financing Authority, recalls that in the early ’90s, just as the Indian economy was being liberalised, Neeraj, still pursuing his BA at Delhi University’s Rajdhani College, launched a cable business. Running cables from their home vcr, he piped Bollywood films and music, children’s programmes and Pakistani serials into the residences of neighbours in that cluster of Delhi Development Authority flats. Within two years, the enterprise had gone from an initial 10 subscribers to over 500. “He was the very first guy to start the process. He had the vision, but Dad wanted him to focus on education so he sold the business,” she says.

|

Monga

went on to secure an MBA from the University of Indore, worked briefly

in India, before taking a loan from Dena Bank for an MBA at the Richard

Ivey School of Business at the University of Western Ontario. Robert

Fisher, who taught Monga here, remembers a student who was able to

“analyse complex situations quickly”. Fisher, who now teaches at the

University of Alberta’s business school, hired Monga for summer

employment. That, though, wasn’t the sort of blue-chip internship his

students coveted. Fisher says Monga did “incredibly well” to “overcome

that barrier” and snagged “the best offer relative to any other student

of his MBA class”. That was at Bain & Company, the same firm where

Mitt Romney, now the frontrunner to become the Republican Party’s

presidential nominee in the US, also worked before forming Bain

Capital.

Monga lasted about a year there. Fortunately for him, Michael

Palmer, a veteran of Bay Street—Toronto’s equivalent of Wall Street—was

planning to set up Veritas, which would concentrate on forensic

accounting. Palmer, now president at Veritas, says, “The concept was

started in 1999 at the peak of the dotcom bubble. We thought there was a

lot of dishonest accounting going on out there.” Veritas came into

being in 2000 and Neeraj Monga was its first employee. The research

wing now has 17 staffers.

The research into Indian equities was Neeraj Monga’s initiative. While Palmer supported the idea, several of Veritas’s partners were sceptical and a degree of persuasion was required before the project was green-lighted. Palmer believes this new venture for Veritas is a need: “I think the Indian markets are at about the same stage as the North American or world markets were when we started Veritas in the first place. There are a lot of companies in India which are overvalued because people don’t really understand the numbers.”

The kernel for the debut analysis, on Reliance, came much earlier. Monga, who had followed the telecom sector, was viewing a presentation on the spinout of Reliance Communications from Reliance Industries: one slide stuck out as anomalous, but he presumed someone in India would comment on that. But there was not a peep for five years. “Ultimately, when I said we can write about India, we went back to dig deeper into that presentation,” he says. The question was how the Ambani family shareholding had gone from 38 to 63 per cent in the change of Reliance Communications ownership, which as Monga saw it, defied logic.

The next report featured another “easy choice”. As Monga says, “Airlines are generally not good business. We just said we’ll look at the annual report of Kingfisher. As soon as we opened the first annual report, we knew something was not right. So we read five years’ worth of annual reports and we figured out this is an effectively insolvent organisation.” In fact, Monga argues that Kingfisher should be delisted from the BSE for flouting Indian accounting standards. For the most recent report, again the real estate sector was another easy choice with DLF the 800-pound gorilla therein. “Anybody who has any experience of India knows the Indian real estate market is rife with underhand dealings,” Monga explains.

Now obviously there’s been a blowback against Veritas’s analysis. A spokesperson for Reliance Communications described it as a “malicious and motivated report containing baseless allegations, masquerading as research”. Lawsuits have been threatened—though not served. Monga isn’t perturbed, though his wife Dimple is, somewhat. The couple is raising two young children, five-year-old Sanjana and one-year-old Arjun, at their house in midtown Toronto. As Dimple Monga says, “Sometimes I’m a little apprehensive that there might be a negative response. I feel these companies can take it very personally.” But she remains supportive of her husband’s crusade to reform accounting practices in India.

Monga, though, is frank that this is not “social service”, as some in India may deem it to be. That’s a reality Palmer underscores: “We’re not doing it out of the goodness of our hearts, we think it’s a legitimate business opportunity and a product which is really needed in India right now.” Veritas’s clients pay a steep rate for access to the firm’s reports, starting at $50,000 in the first year and climbing. The firm certainly wants to broaden its base of clients to India, where it still doesn’t have a footprint, other than working with a consultant.

While its research is sold to institutional investors, some based in Singapore and Hong Kong, Veritas wants organisations like lic and Employee Provident Fund of India to subscribe. “They’re obviously the stewards of the savings of India’s small investors. They have a fiduciary duty to look out for their clients and if we can add value to the investment diligence process, then ignoring us is not in their interest.... It seems to me those managements are sleeping at the wheel,” observes Monga.

Nor is Monga daunted by rumours of the Indian market regulator, SEBI, imposing new regulations on independent equity research. Since Veritas doesn’t yet sell its research in India, it doesn’t need to be registered with SEBI. It is, however, registered with the Ontario Securities Commission and has a chief compliance officer. Still, he believes any such SEBI measure is a “good thing”. He also shrugs off accusations of being part of a bear cartel, retorting that those who are bullish aren’t taken to be “part of the bullshit cartel”. Coincidentally, his office, just off Bay Street, is also next to a bucolic sculpture of placid urban cows, called The Pasture, a counterpoint to the Raging Bull that defines New York’s Wall Street.

|

‘A Pie In The Sky’: Sep ’11 What Veritas said “We believe that kair’s book equity has been wiped out although audited financials pretend otherwise.”  Kingfisher’s response "Very surprisingly, we never got a copy...but they widely disseminated their report to the media which leads me to be suspicious." |

The research into Indian equities was Neeraj Monga’s initiative. While Palmer supported the idea, several of Veritas’s partners were sceptical and a degree of persuasion was required before the project was green-lighted. Palmer believes this new venture for Veritas is a need: “I think the Indian markets are at about the same stage as the North American or world markets were when we started Veritas in the first place. There are a lot of companies in India which are overvalued because people don’t really understand the numbers.”

The kernel for the debut analysis, on Reliance, came much earlier. Monga, who had followed the telecom sector, was viewing a presentation on the spinout of Reliance Communications from Reliance Industries: one slide stuck out as anomalous, but he presumed someone in India would comment on that. But there was not a peep for five years. “Ultimately, when I said we can write about India, we went back to dig deeper into that presentation,” he says. The question was how the Ambani family shareholding had gone from 38 to 63 per cent in the change of Reliance Communications ownership, which as Monga saw it, defied logic.

The next report featured another “easy choice”. As Monga says, “Airlines are generally not good business. We just said we’ll look at the annual report of Kingfisher. As soon as we opened the first annual report, we knew something was not right. So we read five years’ worth of annual reports and we figured out this is an effectively insolvent organisation.” In fact, Monga argues that Kingfisher should be delisted from the BSE for flouting Indian accounting standards. For the most recent report, again the real estate sector was another easy choice with DLF the 800-pound gorilla therein. “Anybody who has any experience of India knows the Indian real estate market is rife with underhand dealings,” Monga explains.

Now obviously there’s been a blowback against Veritas’s analysis. A spokesperson for Reliance Communications described it as a “malicious and motivated report containing baseless allegations, masquerading as research”. Lawsuits have been threatened—though not served. Monga isn’t perturbed, though his wife Dimple is, somewhat. The couple is raising two young children, five-year-old Sanjana and one-year-old Arjun, at their house in midtown Toronto. As Dimple Monga says, “Sometimes I’m a little apprehensive that there might be a negative response. I feel these companies can take it very personally.” But she remains supportive of her husband’s crusade to reform accounting practices in India.

|

‘A Crumbling Edifice’: Mar ’12 What Veritas said “Claims made by management about its ability to execute were fanciful.”  DLF’s response “...is presumptive and mischievous as the analysts have never contacted the company to seek any information or clarification.” |

Monga, though, is frank that this is not “social service”, as some in India may deem it to be. That’s a reality Palmer underscores: “We’re not doing it out of the goodness of our hearts, we think it’s a legitimate business opportunity and a product which is really needed in India right now.” Veritas’s clients pay a steep rate for access to the firm’s reports, starting at $50,000 in the first year and climbing. The firm certainly wants to broaden its base of clients to India, where it still doesn’t have a footprint, other than working with a consultant.

While its research is sold to institutional investors, some based in Singapore and Hong Kong, Veritas wants organisations like lic and Employee Provident Fund of India to subscribe. “They’re obviously the stewards of the savings of India’s small investors. They have a fiduciary duty to look out for their clients and if we can add value to the investment diligence process, then ignoring us is not in their interest.... It seems to me those managements are sleeping at the wheel,” observes Monga.

Nor is Monga daunted by rumours of the Indian market regulator, SEBI, imposing new regulations on independent equity research. Since Veritas doesn’t yet sell its research in India, it doesn’t need to be registered with SEBI. It is, however, registered with the Ontario Securities Commission and has a chief compliance officer. Still, he believes any such SEBI measure is a “good thing”. He also shrugs off accusations of being part of a bear cartel, retorting that those who are bullish aren’t taken to be “part of the bullshit cartel”. Coincidentally, his office, just off Bay Street, is also next to a bucolic sculpture of placid urban cows, called The Pasture, a counterpoint to the Raging Bull that defines New York’s Wall Street.

|

Clearly,

Monga has figured out that Veritas’s research may just be pointing to a

large, systemic disorder in India. That dire warning is delivered in

Monga’s typically outspoken style: “After our telecom report, everyone

said, ‘But the entire sector is in trouble.’ Then, after the Kingfisher

report people said, ‘Ahh, but the airline sector is in difficulty, why

single out a specific airline?’ After our DLF report, I am reading

stories that the entire real estate sector is in a downtrend, and

therefore DLF is no different. The power sector is also in trouble.

Then how come ‘India is a dynamic and growing economy’?” He’s also

clear about the “change” Veritas is targeting. “In India, dealings with

‘related parties’ are the norm, and most ‘related party’ dealings are a

means to siphon funds from the publicly traded entity for the benefit

of majority owners. We will highlight this.”

Unlike those of his ilk, Monga maintains a work-life balance, usually returning home by 6.30 pm. Cooking or watching Bollywood films are favourite forms of relaxation. The prospect of a slew of reports flowing from Veritas this year may just keep India’s corporate behemoths from relaxing though, unused as they are to any sort of intense scrutiny.

Unlike those of his ilk, Monga maintains a work-life balance, usually returning home by 6.30 pm. Cooking or watching Bollywood films are favourite forms of relaxation. The prospect of a slew of reports flowing from Veritas this year may just keep India’s corporate behemoths from relaxing though, unused as they are to any sort of intense scrutiny.