Are you sitting comfortably? Many people are not – and they insist that the way we’ve been going to the toilet is all wrong. By Alex Blasdel in The Guardian

For their 27th wedding anniversary, the Breaking Bad star Bryan Cranston gave his wife, Robin, a gift that promises “to give you the best poop of your life, guaranteed”. The Squatty Potty is a wildly popular seven-inch-high plastic stool, designed by a devout Mormon and her son, which curves around the base of your loo. By propping your feet on it while you crap, you raise your knees above your hips. From this semi-squat position, the centuries-old seated toilet is transformed into something more primordial, like a hole in the ground. The family that makes the Squatty Potty says this posture unfurls your colon and gives your faecal matter a clear run from your gut to the bowl, reducing bloating, constipation and the straining that causes haemorrhoids. Musing about the gift on one of America’s daytime talk shows in 2016, Cranston said: “Elimination is love.”

More than 5m Squatty Potties have been sold since they first crept on to the market in 2011. Celebrities such as Sally Field and Jimmy Kimmel have raved about them, and the basketball sensation Stephen Curry put one in every bathroom of his house. “I had, like, a full elimination,” Howard Stern, the celebrity shock jock, said after he first used one, in 2013. “It was unbelievable. I felt empty. I was like, ‘Holy shit.’” The Squatty Potty has been the subject of jokes on Saturday Night Live, and of adulation by the queen of drag queens, RuPaul. This January, after Squatty Potty LLC hit $33m in annual revenues, the business channel CNBC, which helped bring the footstool to fame through its US version of Dragon’s Den, hailed the device as a “cult juggernaut”.

The Squatty Potty’s success is partly down to “This Unicorn Changed the Way I Poop”, an online ad that launched in October 2015 and has since been viewed more than 100m times. In the video, a fey cartoon unicorn, its rear hooves perched upon a Squatty Potty, Mr-Whippies rainbow-coloured soft-serve ice-cream out of its butt and into cake cones while an Elizabethan Prince Charming details the benefits of squatting to poop. (“I scream, you scream, and plop, plop baby!”) At the end of the video, the prince serves the ice-cream to a gaggle of kids. (“How does it taste, is that delicious? Is that the best thing you’ve ever had in your life?”)

Squatty Potty’s unicorn advert, which has been viewed more than 100m times

At first, many people saw the footstool as little more than a joke Christmas present. But, like fresh bed linen and French bulldogs, the Squatty Potty exerts a powerful emotional force on its owners. “I have one and I have to tell you, it will ruin your life,” a Reddit user called chamburgers recently posted. “I can’t poop anywhere but at home with my Squatty Potty. When I have to poop at work I’m left unsatisfied. It’s like climbing into a wet sleeping bag.” Bobby Edwards, who invented the footstool with his mom, calls people like this “evangelists”. “They talk about it at dinner parties, they talk about whenever they can – about how the Squatty Potty has changed their life,” he told me. He sounded almost mystified.

The popularity of the Squatty Potty, and the existence of its many rivals and imitators, is one of the clearest signs of an anxiety that’s been growing in the west for the past decade: that we have been “pooping all wrong”. In recent years, some version of that phrase has headlined articles from outlets as diverse as Men’s Health, Jezebel, the Cleveland Clinic medical centre and even Bon Appétit. By giving up the natural squatting posture bequeathed to us by evolution and taking up our berths on the porcelain throne, the proposition goes, we have summoned a plague of bowel trouble. Untold millions suffer from haemorrhoids – in the US alone, some estimates run to 125 million – and millions more have related conditions such as colonic inflammation.

Where illness goes, big business follows. The markets for treating these ailments – with creams, surgery and haemorrhoid doughnut cushions – are worth many billions of dollars. Although diet is widely believed to be a contributing factor in these problems (eat your fibre!), lately attention has focused on the possible effects of toilet posture. The renowned Mayo clinic is now conducting a randomised controlled trial to see whether the Squatty Potty can ease chronic constipation, which afflicts some 50 million Americans, most of them women, many over 45 years old.

The Squatty Potty

People often say pooping is taboo, but lately it seems more like a cultural fetish. There are poop emoji birthday parties for three-year-olds, people WhatsApping photos of their ordure to friends, TripAdvisor threads on how to avoid or avail yourself of squat toilets. Through the miracle of online media, you can now discover that, in the past year, both Brisbane, Australia and Colorado Springs, Colorado, suffered reigns of terror by mystery “pooping joggers” who ran around crapping on people’s lawns. There’s a whole YouTube subculture devoted to infiltrating restrooms with vintage toilets and surreptitiously flushing them over and over again (one of thesechannels has more than 16m views). The renowned novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard has devoted passage after passage to his bowel movements. You can even read opinion pieces about the pleasures of evacuating in the nude.

But it’s the banal Squatty Potty that’s doing the most to change not just how people discuss poop, but how they actually do it. “It’s piercing that final veil around bodily use and bodily functions,” Barbara Penner, professor of architectural humanities at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture, and one of the preeminent scholars of the modern bathroom, told me. Perhaps it’s because this small, unlovely stool embodies a grand ambition: to upend two centuries of western orthodoxy about going to the loo.

Shitting, like death, is a great leveller. It renders beluga caviar indistinguishable from tinned ham, a duchess as creaturely as a dog. Even God’s only son may be transformed by the act: the stercoranistes, an early Christian sect, believed in a double transubstantiation, Christ into the communion wafer, and thence into dung. Though at different times and places the excrement of certain personages – be they the Dalai Lama or those with “healthy” gut biomes – has been revered for its healing powers, shit itself is a strict egalitarian. Faecal-borne disease knows no kings; cholera can kill anyone.

People have long tried to resist the democratic power of defecation, imposing rigorous distinctions on and through the act. Since at least the 19th century, bathrooms have been arenas of racial and gender oppression, from the Jim Crow south to the era of trans rights. Hinduism is infamous for its caste system, according to which the Dalits, formerly known as “untouchables”, are forced to manually dispose of the faeces of higher castes. In Kenya, the nomadic Samburu use personal trowels to cover their excrement; the beading on the handle expresses the owner’s status within the tribe. In the US and UK, the bathroom is often, per square foot, the most expensive room in the home. Wedgwood, who made your posh grandmother’s dinner set, made her posh grandmother’s toilet pan.

An Ancient Egyptian toilet bowl from the New Kingdom period (1600-1100 BC). Photograph: Science Photo Library

The recorded history of human defecation can be read as a series of attempts at differentiation: how do we separate our excrement from our bodies, our sewage from our homes and cities? How do we keep the sounds and smells of our bodily functions from infesting other people’s senses? How do we enforce social hierarchies by dividing the bodies of the powerful from the bodies of the oppressed?

To these questions, the bathroom with its seated water closet, or flush toilet, was a surprisingly recent but remarkably potent answer. Though sit-down privies and latrines have existed at least since Egyptian antiquity, for almost all of history the vast majority of Homo sapiensdefecated squatting, in the open. As the planet filled up and humans clustered together in cities over the second half of the previous millennium, open defecation became a scourge, leading to rising rates of diseases such as dysentery – still a major problem in parts of the world without modern sanitation.

It’s generally held that the water closet was invented by an English nobleman at the end of the 16th century. But it wasn’t until the the industrialisation of Britain’s potteries and ironworks in the mid-19th century that water closets ceased to be the preserve of the wealthy. As they spread to homes across northern Europe, toilets led to revolutions in sanitation, medicine, social relations and even psychology.

With more and more people going to the bathroom at home and in private, defecation became a solitary and almost unspeakably vulgar act. Some wrongly believe that other people’s bowel movements elicit universal disgust. But as recently as the 16th century, a treatise on etiquette scolded well-to-do Europeans not to flaunt the stinking cloth with which one wipes one’s arse. For several hundred years, into the 18th century, English monarchs did their business in front of literal privy councils while enthroned upon an upholstered box containing a chamber pot. Indeed, “social defecation” has been observed across times and cultures. In the 1970s, the anthropologist Philippe Descola documented it among the previously uncontacted Achuar people in the Amazon; open-plan, ni-hao (“hello”) bathrooms are still common in many parts of China.

In the period of late empire in which it was popularised, the private toilet and bathroom came to be seen as the sine qua non of European achievement. “The Civilisation of a People can be measured by their domestic and Sanitary appliances,” the pioneering Victorian sanitary engineer George Jennings wrote in the 1850s. It’s a sentiment still shared by many a bewildered western tourist when first confronted in parts unknown by what appears to them to be a tiled hole in the ground.

A ‘close stool’ chamber pot, circa 1670-1705, from Hampton Court Palace. Photograph: Royal Collection Trust

So profound is the link between the water closet and people’s vision of the modern west that the German architect Hermann Muthesius predicted in 1904 that “when all the fashions that parade as modern movements in art have passed away,” the bathroom, with its beautifully functional fixtures, would be “regarded as the most eloquent expression of our age.” Edward Weston, one of the fathers of artistic modernism, agreed. After spending two weeks in the autumn of 1925 photographing his toilet, he pronounced its “swelling, sweeping, forward movement of finely progressing contours” a rival to the most celebrated sculpture of so-called western civilisation, the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

Like any technological solution, however, the water closet set in motion new problems. The use of water to dispose of faeces has been “a central element of our perilous fantasy that the planet was created for human convenience,” one Canadian scholar has written. Alongside improved hygiene and stronger taboos also came an explosion in various so-called “modern” diseases, such as haemorrhoids and constipation, which were attributed to seated toilets. One 20th-century physiotherapist described constipation as “the greatest physical vice of the white race”.

Antidotes, such as low-to-the-ground toilets known as “health closets”, which would allow for a half-squat position, have been on the market in Britain since at least the 1920s, Barbara Penner notes in her book Bathroom. Around mid-century, a predecessor of the Squatty Potty was on sale at Harrods. In the mid-1960s, in the US, a Cornell University architecture professor named Alexander Kira proposed a number of squatting and semi-squatting toilet designs in his monumental study The Bathroom, in which he called the seated toilet “the most ill-suited fixture ever designed”. Yet no solution to the problems posed by the modern toilet really took off. Until now.

The most primitive things sometimes require extraordinary sophistication to produce. The passage of a humble turd demands the orchestration of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system, muscles skeletal and smooth, three anal reflexes, two sphincters and a weight of cultural knowledge about where and when it’s appropriate to go. It is a “masterful performance”, writes the German scientist Giulia Enders in her international bestseller, Gut.

On its descent through our bodies, faecal matter traverses a landscape marked by the poetry of the gastroenterologist: the flaps of tissue that project into the rectum, known as the “valves of Houston”; the bouquet of blood vessels contained in the “anal crypt”. As the rectum fills with the products of digestion, it signals, through nerves running into the sacral region of the spinal cord, that defecation may be necessary. The internal and external anal sphincters then begin a culturally mediated pas de deux, the former pressing for release and the latter restricting discharge until the opportune moment.

When that time comes, a person may perform the Valsalva manoeuvre, increasing the pressure inside the abdomen by exhaling against a closed airway as if popping one’s ears on a flight. The pelvic floor muscles relax, the perineum descends, and the external anal sphincter opens up, delivering your creation into the world. It takes mammals about 12 seconds to pass a stool, with humans accomplishing the task at a rate of one to two centimeters of faeces per second. In a deep squat, with our buttocks about 150mm from the floor, it takes us under a minute, on average, to go from initiation to a sense of elimination, according to one study.

Ancient Roman communal toilets at Ephesus in Turkey. Photograph: Leonid Serebrennikov/Alamy

But to perform this act on a seated toilet, which can range from a standard 13 or 14 inches tall to a “comfort height” of as much as 20 inches, more than doubled that time. Imagine that your bowels are a prison revolt, and the inmates – your faeces – are trying to storm the gates. If they have to take a hard corner, they’re going to lose momentum and get trapped. With a straight shot, they can easily come pounding down the door. When we sit to defecate, we need to force our feces through a bend in our rectum created by a little hammock-shaped muscle called the puborectalis. While standing or sitting, the puborectalis helps to keep us continent by cinching our bowel closed. In a full squat, that cinch relaxes, the bend or “anorectal angle” opens up, and intra-abdominal pressure rises, reducing the need to push.

This is an eminently good thing. Straining to force your crap around the puborectalis can induce haemorrhoids, intestinal inflammation, fainting – even strokes, brain haemorrhaging and heart attack. One theory has it that the pain from a thrombosed haemorrhoid was so distracting that it cost Napoleon the battle of Waterloo. Elvis Presley’s personal physician famously speculated that a cardiac arrest brought on by straining is what finally did the King in. The kink in your tail may also give you a backlog of faeces that’s not able to leave the gut on schedule. This “faecal stagnation” is thought to be a factor in colon cancer, appendicitis and inflammatory bowel disease. It’s estimated that the average adult produces over 300 pounds of faeces in a year; legend wrongly but tellingly has it that John Wayne died with 40 pounds, or more than a month’s worth, of crap in his gut, and Elvis with something like 60.

The Squatty Potty was born in similarly unfortunate circumstances. “I was constipated my whole life,” Judy Edwards, the Squatty Potty co-creator, admitted in 2016. For a long time, she had been using a little footstool in the bathroom. “We’d teased her about it for years, about this stupid poop stool she’d bring on vacation,” her son Bobby told me. But the footstool wasn’t quite right, so one day, after Bobby, who was working as a building contractor, started taking design classes, Judy asked him to take a look at it. “She took me to the bathroom and she showed me how it worked, and as she was sitting there explaining it to me, it’s like a light went on in my head,” Bobby said.

With paint cans and phone books, they determined the perfect height and width for a new stool. The template Bobby created became the design of the first Squatty Potty. “It was hilarious,” Bobby said. “I thought, this is brilliant, I can picture the infomercial now.” The Edwardses began manufacturing the first Squatty Potties in their garage in 2010.

But sales were sluggish. The family is from St George, Utah, a high-desert town where 70% of the 80,000 residents are Mormons like Judy – not the sort of folks who gossip about their bodily emissions on a regular basis. “She’s a believer, she’s super faithful, she goes to temple every Sunday,” Bobby said of his mother. “That was an interesting dynamic when we were creating this. We embarrassed her a lot.” (This wasn’t so much of a problem for him, Bobby added; he left the church at 17, when he came out as gay.) One local woman told Judy she should be ashamed of what she was producing.

People’s reluctance to embrace the Squatty Potty wasn’t helped by the fact that the Edwardses promoted it at the local trade show with a skeleton on a toilet. (Although the Squatty Potty itself is designed to be as discreet as possible – the standard, white plastic version almost blends away into the colourless expanse of many modern bathrooms – the marketing could never afford to be minimalist.) But friends and family to whom the Edwardses had gifted Squatty Potties where pleasantly surprised by the stools, so Bobby and Judy carried on. St George might not have been ready for the Squatty Potty, but it was about to make a bigger splash than they could ever have imagined.

One of the dizzying ironies of our time is that an earlier reverence for the trappings of civilisation seems to be giving way to a pervasive distrust of modern habits and modern technology. Cars have ruined cities, atomised people and poisoned the atmosphere. Plastics have poisoned the seas. Deodorants and air fresheners have poisoned us. Antibacterial soap has led to the rise of superbugs. Your chair is killing you. So are your running shoes. If you listen to Jared Diamond or Yuval Noah Harari, the development of agricultural civilisation may be the gravest mistake humans ever made. For vigour and vitality, you should renounce thousands of years of grain-based eating and return to a paleolithic diet.

We have even come to look upon the toilet with a jaundiced eye. As a result, there’s something beguiling about the suggestion that the Squatty Potty, for the few moments we mount it, allows us to return to a more natural state. “It’s all about basic mechanics,” Bobby Edwards told an interviewer in 2014. “It’s about taking it back to the way it was done thousands of years ago.”

But for all its squat-like-our-ancestors logic, it’s no surprise that the rise of the Squatty Potty tracks the spread of social media. The vogue for lifestyles that are cleaner, greener, more organic, paleo, supposedly more in tune with human evolution, and closer to nature has largely spread through hi-tech means. (To a dieter’s exasperation, there seem to be more paleo apps than paleo-conforming appetisers.) One of Squatty Potty’s earliest significant sales boosts came in 2011, from a vegan blogger with 75,000 followers. It has also been lauded by influential blogs and websites such as The Paleo Mom, Wellness Mama and the Mother Nature Network.

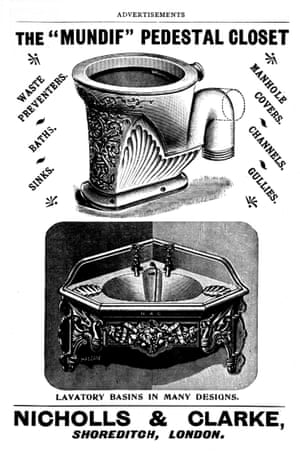

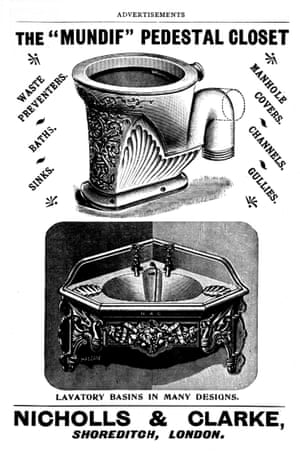

An advert for a pedestal closet toilet, 1899. Photograph: Science History Images/Alamy

It’s a commonplace that social media such as Instagram pressure us to present perfect versions of ourselves: here we are, beautiful and happy, living our best lives #blessed. Like the earlier craze for colonics, the fad for clean eating and the mania for mindfulness, the Squatty Potty seems to translate this perfectionism to our internal states. “The Squatty Potty almost turns the body itself into this efficient flushing mechanism,” like the complex sewage systems we’ve constructed, Barbara Penner said. “There is this element of ‘Let’s empty ourselves out’.” The implicit notion seems to be that ridding ourselves of “bad” foods, unthoughtful thoughts and every last pellet of faeces can help us achieve not only health, but something approaching a state of purity.

At the same time, social media has had other, more humanising effects. In the 1970s, Alexander Kira of Cornell University diagnosed Americans with a psychological and cultural aversion to squatting, as well as to talking openly about our basest bodily functions. Today, after little more than a generation, people are opening up about defecation in a way that was presaged by early, faeces-focused social media sites such as poopreport.com and ratemypoo.com. These sites were often anonymous and almost completely free from the cultural censors that ran traditional media. By contrast, today people happily put their names to stories about their bowel movements, and you can read about anal fissures in the pages of the New York Times.

This unabashed attitude is a major part of the Squatty Potty’s appeal, too. By combining the science of the puborectalis with the whimsy of crapping unicorns (and, in a later ad, gold-bullion pooping dragons), the company is trying to transform the private indignity of awkward bowel movements into an almost universally shared joy. “If you’re a human who poops from your butt,” this stool’s for you, the prince in the unicorn video avers. People were listening: in the three months after the video aired, the company sold 195,000 footstools, and grossed more than $7m.

The Squatty Potty website features a nearly endless feed of Instagram testimonials for its products, which now include a nine-inch version, a bamboo version, a kids’ version that looks like a hippopotamus, stools in black, grey and pink, and a host of other faeces-related goodies, such as witchhazel-infused foam that turns standard-issue toilet paper into flushable wet wipes and a plunger shaped like the poop emoji. New footstools are shipped with a pin-on badge that reads “I POOPED TODAY!”

But this sudden enthusiasm for disclosing private habits masks a deeper truth: shitting and shit have never stopped being profoundly public. Behind the closed door of the bathroom have always lurked the public structures – the pipes, the laws, the labour – that manage human waste. And, behind those, lie defecation’s two inescapable conditions: our bodies and the planet.

There’s a set of common fallacies that equate the “natural”, the “healthy” and the “good”. We often decide that something we think is good must also be healthy (that morning cup of coffee or nightly glass of red wine, say) or natural (polyamory for some, religion for others). But we also like to run things in the opposite direction: if we believe something is natural, whatever that means, we often assume it must also be healthy and good. Our caveman ancestors, in their wise state of nature, ate nothing but acorns and barbecued mammoth? Me eat nut butter and grass-fed steak!

Squatting may be natural, but the question remains: is the Squatty Potty also good? Post Darwin, we no longer tend to believe a couple of hundred or thousand years of human ingenuity can improve upon the immemorial march of evolution. Those who think the water closet has been vindicated by history ignore how contingent, and in some ways irrational, modern sewage systems with seated toilets really are. This is underscored by the fact that billions of people regularly use modern, hygienic squat toilets to poop.

So it does seem plausible that the Squatty Potty might return us to a sort of pooping Eden. But the limited research that exists on footstools is equivocal. In three studies that were either uncontrolled or had very small sample sizes, there was evidence that squatting to defecate has positive effects on the ease and extent of elimination. When it came to simulating a squat by using a footstool, though, the results were inconclusive. The semi-squat position did not appear to open the anorectal angle, or reduce the amount of straining needed to go, though the studies were not rigorous enough to establish anything approaching a scientific fact.

That doesn’t mean you need to hit the squat toilets that still exist along the French motorway or – to the horror of the Daily Mail – in Rochdale’s Exchange shopping mall. Dr Adil Bharucha, who is leading the Mayo clinic’s randomised controlled trial of the Squatty Potty, hopes that his study will establish more conclusively whether the Squatty Potty works, and why.

Of course, even if it does cut down on haemorrhoids and constipation for many people, this doesn’t make the Squatty Potty natural. Rather, the stool shows it’s actually impossible to go “back.” “We are locked into these systems and patterns of use,” Barbara Penner said. “But the Squatty Potty intervenes into that system and modifies it without actually requiring a massive retrofitting of the system.” (One Reddit user suggests crapping in 10-inch stiletto heels.) It’s also pleasantly low-tech, something of a riposte to wifi-connected toilets that heat your bum cheeks and analyse your urine for you – and whoever else has access to the data.

The philosopher Slavoj Žižek has claimed to discern in the toilet designs of Germany, France and England basic ideological differences between Europe’s three principal cultures. Germany’s “lay and display” toilets, which allow excrement to rest on an exposed shelf for inspection before being suctioned away, reveal a blend of conservatism and contemplativeness. French toilets, designed to remove faecal matter as swiftly as possible, express that people’s revolutionary hastiness. Anglo toilets reflect a pragmatic medium: according to Žižek, “the toilet basin is full of water, so that the shit floats in it, visible, but not to be inspected”.

If the Squatty Potty expresses a worldview, it may be an almost evangelical one: a yearning to purify and perfect ourselves, to be saved from the messiness of this world. Part of the fantasy of the Squatty Potty, Penner pointed out, is that it will completely separate our faeces from our bodies the way sewerage purports to separate it completely from our lives. (Bobby Edwards says his hope was simply to create a successful business, and to help people.)

It’s tempting to read into this lust for evacuation an anxiety about our current age, when our rejectamenta of various kinds are bearing back down on us from all sides. We are now realising that there is no “away” to which we can flush our excrement; it is always coming back to us in some form, be it faecal bacteria in seafoam, or the hundreds of thousands of pounds of human excrement that climbers have left on the slopes of Denali, north America’s highest, and among its wildest, peaks. The complete evacuation of faeces from our bodies and our world is a chimera.

But the Squatty Potty also represents a more worldly sort of devotion. Our anal sphincters “are concerned with some of the most basic questions of human existence,” Giulia Enders, the scientist, writes: how we navigate the boundaries between our internal and external worlds. One might add the spiritual world, too. The simple hedonism of a full bowel movement reminds us that the body is the ultimate seat of the soul. Like Bryan Cranston, we all want the ecstacy of elimination, the self-love we feel after a really good shit.