The statistics on inequality – those used, for instance, in Thomas Piketty’s bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century – only include the income and wealth the taxman sees. So how high is inequality when also accounting for what he doesn’t see? Recent leaks from tax havens suggest the gap between the rich and the rest is even wider than we think.

Tax records are invaluable for the study of economic inequality. They contain detailed information about the income (and, in some countries, wealth) of taxpayers. Much of this information comes directly from employers and banks, and is therefore reliable. And because tax records exist as far back as the early 20th century, they can be used to shed light on the long-term evolution of inequality.

The graphs published on the World Wealth and Income Database, for example, show just how powerfully this information can inform the public debate. The top 1% income share is now closely scrutinised by journalists and policymakers in the US, where the rise of inequality has been particularly extreme; it even gave the Occupy movement its motto: “We are the 99%.”

But for all their merits, tax data raise an obvious issue: by their very nature, they entirely miss tax evasion. Is this a serious problem? That depends: if tax evasion is equally prevalent among rich and poor, measured inequality will be unaffected. But if the rich dodge taxes more than others, tax records will underestimate inequality.

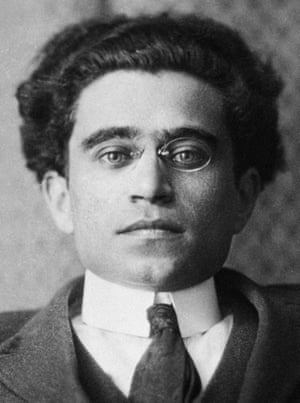

At the time of the 2007 leak, HSBC Switzerland was a major actor in the offshore wealth management industry. Photograph: Harold Cunningham/Getty Images

Before now, there hadn’t been any attempts to address the measurement of global tax evasion systematically. The reason is simple: the lack of comprehensive information about who skirts taxes. The key data source used in rich countries to study tax evasion is random tax audits – but these audits do not capture tax evasion by the very wealthy, because few of them are audited, and because random audits fail to detect sophisticated forms of evasion involving shell companies and hidden accounts.

The higher one moves up the wealth distribution, the higher the probability of hiding assets

In our recent study, however, we exploited a massive trove of data leaked from HSBC Switzerland, the so-called HSBC files, to fill this gap. In 2007 a systems engineer, Hervé Falciani, extracted the internal records of HSBC Private Bank, the Swiss subsidiary of HSBC. In 2008, Falciani turned the data over to the French government, who shared it with foreign tax administrations. The documents leaked by Falciani included the complete internal records of more than 30,000 clients of this Swiss bank in 2006-07.

At the time of the leak, HSBC Switzerland was a major actor in the offshore wealth management industry. It managed US$118.4bn – about 4% of all the foreign wealth managed by Swiss banks. This is a unique source of information through which to study tax evasion, because the leak can be seen as a random event, and it comes from a large (and, the available evidence suggests, representative) offshore bank.

We also made use of the Panama Papers, which last year revealed the identity of the shareholders of shell companies created by the Panamanian firm Mossack Fonseca. Just as with HSBC, this leak is valuable as it can be seen as a random event and involves a prominent provider of offshore financial services. The Panama Papers, however, have one drawback: they do not allow us to estimate how much tax was evaded (if any) by the owners of the Mossack Fonseca shell companies. It is not illegal per se to own shell corporations in Panama or elsewhere.

Leaked documents revealed the identity of the shareholders of the shell companies created by the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca. Photograph: Kin Cheung/AP

We combined random audits with these new sources of information to shed light on who really evades taxes in Denmark, Norway and Sweden – and the results are striking.

The higher one moves up the wealth distribution, the higher the probability of hiding assets. Scandinavian households in the top 0.01% of the wealth pyramid – the ultra-rich, who own more than $40m in net wealth each – are 250 times more likely than average to hide assets. Furthermore, the ultra-rich HSBC customers had considerably more wealth in their accounts than other customers – so although they were very few in number, they owned around half of all the wealth hidden at HSBC.

In Norway, the super-wealthy appear to be 30% wealthier when all the wealth hidden in tax havens is taken into account

This pattern is not specific to HSBC or the Panama Papers. Over the last few years, thousands of Norwegians and Swedes have voluntarily declared previously hidden assets under a tax amnesty. Here again, the super-rich are found to own half of the total amount of offshore wealth.

So what are the consequences for inequality? At the very top of the pyramid, it is much greater than previously estimated. In Norway, where the available wealth data is particularly detailed, the super-wealthy appear to be 30% wealthier than previously thought, when all the wealth hidden in tax havens is taken into account. The share of wealth owned by the top 0.1% increases from 8% to 10%.

Since Scandinavians generally pay their taxes and hide little wealth in total, our results are likely to be even stronger in Great Britain and elsewhere. A more accurate measurement of tax evasion would likely increase inequality levels even more than in Scandinavia.

These results underscore a basic truth: in a world where wealth is globalised and where a big industry has specialised in helping the ultra-rich avoid and sometimes evade their taxes, our ability to track great fortunes – and to tax them appropriately – faces considerable challenges.

But does this mean nothing can be done? Not at all.

It is possible to collect much better information on wealth and its distribution. Progress has already started in this area, as a number of tax havens have agreed to automatically exchange bank information with foreign countries’ tax authorities – a major evolution since the time of the HSBC leak.

But this policy faces an obvious issue: what are the incentives for offshore bankers to provide truthful information? After all, these are the same people who for decades have been hiding their clients behind shell companies, and sometimes even smuggling diamonds in toothpaste tubes or handing out bank statements concealed in sports magazines – all of this in violation of the law and the banks’ stated policies. Yet it still should be possible to secure their cooperation, if they face stiff enough sanctions for non-compliance.

More broadly, the key to successfully fighting tax evasion is to change the incentives for the providers of wealth concealment services. Over the last few years, a number of banks have pleaded guilty in the US to criminal conspiracies to defraud the Internal Revenue Service – yet they were able to keep their banking licences, and the fines they had to pay paled in comparison to their profits. A more ambitious approach would put criminal organisations out of business. If tax evasion ceases to pay, it will disappear.